‘It’s not a good thing, Ron, to be queer. …/(…)/(…) After a time you’ll find the right girl. (…) But you must look. You are a normal person who has been infected. You must get it out of your system. Being queer’s no good for you. It cost Julian his life’ (published 1953).[1] Rodney Garland’s (2014 Valancourt reprint) The Heart In Exile Richmond, Virginia, Valancourt Books.

Paolo Freire, a name of great moment in education when I was at grammar school in the 1960s, used to talk about knowledge as a means by which the marginalised and the oppressed internalised their own marginalisation and oppression. In the title quotation from the novel that I use in this blog, a knowledgeable, sensitive and perceptive (for so he is constantly proven by the novel to be) middle class queer man, who is also a ‘psychologist’, Dr. Tony Page, instructs a working class man, Ron, that he is mistaken in thinking that he can choose to be ‘queer’ when Ron is, in fact whether he knows it himself or not, ‘normal’. If you are normal, you will remain or revert to ‘normality’, although it is possible to be ‘infected’ or (the word used in an earlier context) ‘corrupted’. This is a most perfect illustration of what Freire has to say about the role of knowledge in maintain and internalising a world of pre-established hierarchies being different people. However, Dr Page is a character in a novel and we cannot assume that his knowledge has authority except to himself.

The basis of Page’s ‘knowledge’ is quoted with what seems to be appropriate academic and professional authority at a point in the novel where Tony explains the limited but necessary, in his view, moral perspective demanded of people who are born with, rather than merely socially acquire, ‘queerness’. But there are features of this support of a knowledge about queer men that are ambivalent, to say the least.

The only moral scruple in my emotional life was against corrupting someone who was normal, especially if he were young. … Stowasser and Hyde in New York and Pollner at St. Gabriel’s, all serious experts on inversion and as “normal” as they make them, held the view that in their experience no really normal person could be made into an invert through seduction at an early age. The person who had no predisposition might play, but would revert to normality later, the one, on the other hand, with a predisposition to inversion might well sooner or later become an invert.

I may have been wrong but I felt I had no right to provide the decisive push towards an anchorage which made life more miserable than the so-called normal attitude.[2]

The attitude to knowledge here is difficult to gauge. The moral crux of the novel does later hinge on whether Page will use his class, status and age to seduce Ron, a working class man alienated temporarily from his own class. Page does not, which both illustrates his continuing morality and fails to test the theses of ‘Stowasser and Hyde’ and ‘Pollner’ that his moral concerns may be irrelevant. Their ‘research’ (fictional though it may be in fact) suggests it is not possible to infect or corrupt others, if those words are taken to mean, making someone queer who originally was not.

But what does this suggest about Garland’s authorial take on these supposedly academic/medical views of what constitutes queerness. Garland himself is somewhat of a fiction, a very English nom de plume for the Hungarian Adam De Hegedus.[3] My own searches failed to discover intellectual workers in the history of twentieth century ‘sexology’ named Stowasser and Hyde or Pollner. My suspicion is that they too are entirely fictional and this in itself suggests that we approach the authority of Dr. Page with some kind of reserve as to its validity. After all, Page’s statement is actually as ambivalent about the validity of ‘sexological’ science as he is about folk beliefs regarding the ‘social problem’ posed to young relatively powerless males by the existence of powerful gay men. Chris Waters, the best historian of this transitional period in British queer history, argues that the generalised historical drift of twentieth century queer history revolves around how the ‘social being’ of the period’s homosexual groups and individuals was modelled intellectually. But, in passing, he also illustrates that, whatever the direction of travel transitions in the representation of queer men can be said to be, the expression of queerness often contained a potent mix of medical, ‘social’ problem’ and ‘social group’ models rather than one of these. Waters calls these mixed representations ‘slippages’ between distinct representations in which so often medical language persisted, even if it was now more metaphorical of other kinds of influence than the strictly biological.[4] This ‘slippage’ of the medical into the issue of social transmission of queer lifestyles explains in part why Page can describe Ron as ‘infected’ where he may mean ‘corrupted’.

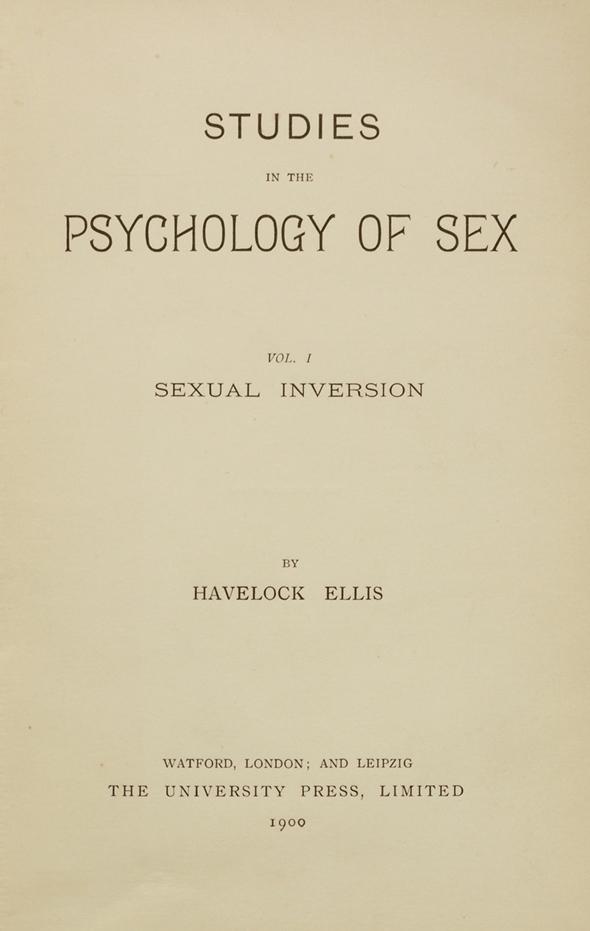

However, the choice of the common medicalised term from the period, the ‘invert’ is based on the concept of genetic ‘sexual inversion’: Kraft-Ebbing’s term postulates in this concept a genetically transmitted inverse relationship between the internal sexual nature of people thus identified and their external sexual appearance in such ‘born’ inverts. This is not then a true intersexuality, where physical characteristics are mixed but a mismatch between gender binaries used to describe the psychological and the physical, although here again, the psychological aspects are assumed to be innate.

Hence the use of the term ‘invert’ is not just a matter of terminology. It throughout implies an analysis where true inverts are distinguished from ‘normal’ men ‘corrupted’ or ‘infected’ by inverts to believe that they too may be inverted. It is precisely this point Page addresses with Ron. We shall see gender characteristics used throughout to distinguish inverts from ‘normals’. My interest is in the fact that what is being explained is, in fact, the basis of an understanding of how and why inverts take on hierarchically advantaged social positions in society. Such a move is necessary in a novel where the ‘problem’ is how men with unchallenged social power over a working-class thought of as vulnerable come to pose a threat to the latter, as does Julian Leclerc, we are to discover, and even, potentially, Dr. Page himself. The problem with inverts is clearly their likeness to women – a rather shocking finding – as in this quotation of Page himself.

‘The invert, or rather a type of invert, sometimes has a feminine elasticity which can turn him into more than a successful social climber. It enables him to adopt the culture of a higher group in all senses, including the moral’.[5]

That femininity contains problematic characteristics vis-à-vis the masculinity of the period is most shown in the strangely unappealing characteristics of Miss Ann Hewitt, whose nose for marriage is decidedly that of someone concentrated entirely on social advantage and calculation. Whilst she may have been therefore socially matched to Julian Leclerc had he chosen the option of heterosexual marriage over suicide, her problem remains that she is insensitive to the appeal of ‘normal men, unlike Julian and other inverts. The latters’ feminised sensitivity (that which equips Page as a psychologist his mentor tells him) attracts them precisely to ‘normal’ over ‘invert’ men and explains the powerful sexual pull to working class men in ‘the novels of the younger university men of the ‘thirties’.[6] Working class men in this novel are often treated by its characters as the type of the normal – they together with their big ‘hands’.

One of the clearest expositions of this is Dr. Page’s explanation to Terry, his live-in servant and later candidate for domestic and sexual partner. Problematic ‘homosexuals’ are not only the bearers of a neurosis (the nearest the novel gets to the views then of institutional psychoanalysis) but they are unethical about the use of sex to attract men in the same way, it is merely assumed, as women have always been capable. It is quite shocking really.

“… I’m equally certain that for a number of people inversion is an advantage.”

…

“… it is one field in which the invert has certain advantages in much the same way as a pretty girl. … certain people, by virtue of being homosexual, can profit enormously through having affairs with people in a position really to give something. Not money and presents, because that’s just prostitution, but …”.[7]

I find the use of the word ‘profit’ double-edged here because although it intends, as the point develops, to indicate ‘spiritual and emotional’ advantage, its primary meaning of monetary and resource gain remains intact through its denial. Pretty girls aim to profit by men. In fact this is precisely the profit Page, apparently unknown to himself here, is offering to Terry. Social advantage to Terry through Dr. Page’s person, is masked by the ‘spiritual and emotional’ capital he has on offer and that it is one function of the novel itself to demonstrate. I doubt however whether Terry will find this advantage much modifies his role in Page’s domestic life as the equivalent of a paid servant.

That this novel becomes in fact a means of preserving the status quo of middle and upper class men, but especially promoting the former, is clear (or should have been) in the reference to the ‘younger university men of the ‘thirties’; he is thinking clearly I would say here of Christopher Isherwood, W.H. Auden and Stephen Spender. The link between the latter, their passion for ‘real’ and ‘normal’ men is, and Communism (by virtue of the idealisation of the working class as a repository of such men), is explained.

Much of the novel is an explanation of why this link was wrong-headed and harmful not only to social stability of a hierarchical society but also for working-class men, like Ron, as well. Such judgements take the form of learned perceptions. In an ‘invert’ party, blessed with the presence of ‘a couple of sailors, both young, earnest, good-looking, semi-normal and “haveable”’, Page learns that, ‘sex, normal or abnormal, was not the great social unifier that the wishful often claim’.[8] Such learning eventually hardens into theory.

The results of the social revolution had brought many to their “senses” with a vengeance. Having gone through the guilt complex of being middle class or upper class in the ‘thirties and early ‘forties. they had, after the war, become ambitious and mean and as careeristic as conditions allowed. All this was understandable, especially from a group of people who stood to lose so much, not to speak of the fact that Communism … had turned out to be a false god, and a dangerous one at that.[9]

In the end, and at the same point as the above, Page also undermines even the notion of the apparently greater masculinity of the working-class who only ‘seems more masculine’(although ‘in some ways he is’ – remember those large hands) to the inverts amongst the higher classes. That appearance is based he argues on a socially widespread ‘guilt complex’ in the queer sons of the ruling classes based on their need or wish to find a man to suit their internal feminine needs.

Before I finish these observations I want to add a little more to the assertion that equating queer men with the internal feelings of women is actually quite problematic. Page learns he has an ‘undeveloped heart’, but this, in itself, a symptom of the male invert’s internal feminisation that has not been tempered by social realism.[10] The real problem for women in Garland’s society is that their social success, according to that society, turns upon sexually attracting a higher class man, as Ann Hewitt illustrates. Women, like Ann, have learned this the hard way and subordinated passion to calculation. Ann, for instance, insists to Page that she should not be too linked to Julian once his suicide disrupts her intentions. When he reclaims her photograph from the latter’s home, Page is instructed not to bring the frame of the picture, since that is evidence of that link. Inverts have yet to learn such lessons – hence their socially inappropriate valorisation of young working class as men. Such valorisation is a putting of the sexual before social propriety. An undeveloped heart is the same heart as leads queer men to the impractical option and ‘moral’ option of preferring sex to love. He calls this ‘satyriasis’, after the figure of the half-goat ithyphallic mythical Greek figures. It is based on a narcissistic preference for one’s own points of attraction after all and explains the absurdity not only of ‘old maids’ but of the figure he may become: a ‘seedy, old homosexual doctor haunting the twilight in twentieth-century England’. The paragraph ends:

Like most inverts, he had an agonising fear of an old age in which his physical attraction would diminish, but not necessarily as slowly as his ardour’.[11]

This is about becoming the tragic figure which is a fate that threatens those who depend only upon the ardour of young masculinity in both themselves and their sexual objects to achieve either relief in their hearts or stable and enduring union outside of poverty and/or marginal status.

These novels repay our attention of course but they shouldn’t be treated as mere posts in the development of a liberated sexuality but of a sexuality that can, like any other, find uncomfortable accommodation in the home of oppression as an oppressor as well as the oppressed, or as a combination of both.

Steve

[1] Garland (2014: 227)

[2] ibid: 79f.

[3] Neil Bartlett in ‘Introduction’ in ibid: vi.

[4] Waters, C. (2013: 205) ‘The homosexual as a social being’ in Lewis, B. (ed.) British Queer History: New approaches and perspectives Manchester & New York, Manchester University Press, pp.188-218.

[5] Garland (op.cit: 116)

[6] ibid: 116

[7] ibid: 142. My italics.

[8] ibid: 171

[9] ibid: 219

[10] ibid: 224

[11] ibid: 217)

9 thoughts on “‘It’s not a good thing, Ron, to be queer. … After a time you’ll find the right girl. … But you must look. You are a normal person who has been infected. … Being queer’s no good for you. It cost Julian his life’ (published 1953).[1] Rodney Garland’s ‘The Heart In Exile’”