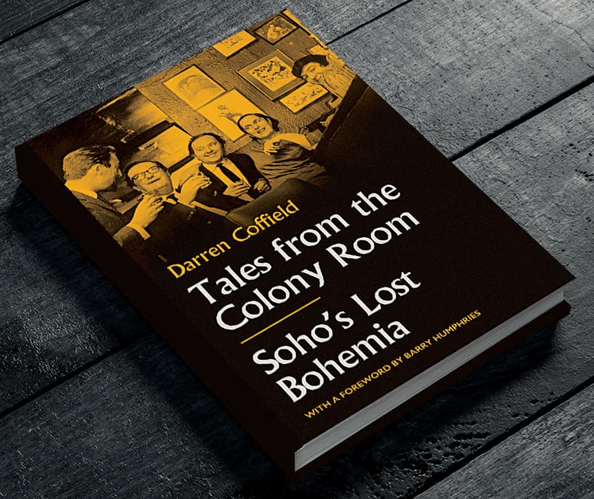

‘The club world is a shifting one. A club has its moment, and fades; people pass by or pass on; … Muriel is the exception – she continues’.[1] Learning about the passage of time and persons in Darren Coffield’s (2020) Tales from the Colony Room: London’s Lost Bohemia London, Unbound.

This blog was a piece I felt I had to write for myself to mark a book I felt to be more portentous about the nature of art than its author probably intended. I am not happy that the argument has, or could be, developed and it relies on quite a bit more assertion and generalisation than evidence. But, as one ages, maybe you just feel the need to get your feelings out there when significance strikes up from the mass of publications gone through in your reading. In part, it is an unacknowledged sigh for a world lost to me. As a student I loved Soho though it was tamer than the world that was actually happening in Dean Street, whilst we had a pizza and took our own wine in Bateman Street round the corner and felt part of a much more adult world (that it possibly wasn’t) which accepted and embraced diversity and death. Well here goes.

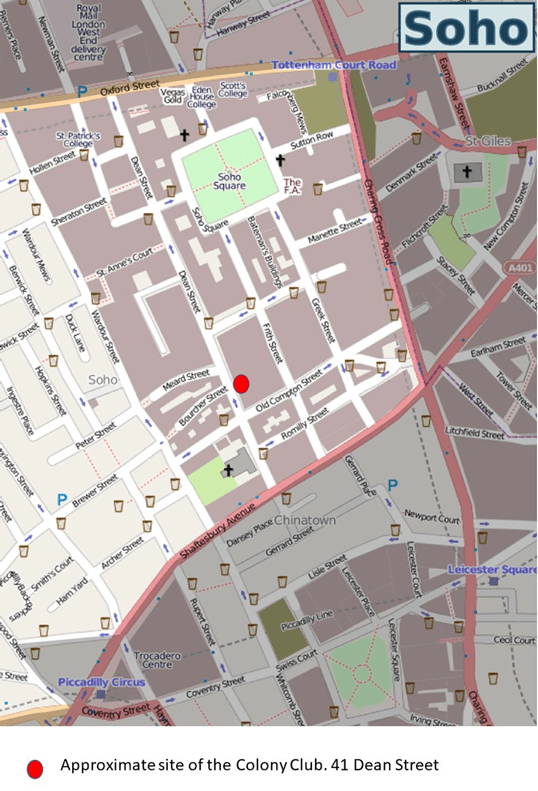

In an interview about his book following its publication, Darren Coffield says of the Colony Club, a small afternoon drinking club at 41 Dean Street, London WC!. : ‘Like so many before me, I felt completely at home, washed up on the shore of a luscious green bohemian paradise’.[2] I like to think that Coffield identified the Club as a kind of magic land and himself and other past and present members of that Club as latter-day versions of Tennyson’s The Lotos-Eaters:

A land where all things always seem’d the same!

And round about the keel with faces pale,

Dark faces pale against that rosy flame,

The mild-eyed melancholy Lotos-eaters came.[3]

A strange but sad paradise is described in both contexts where the appearance of constancy (where ‘all things always seem’d the same’ and, in the case of the Colony Club, where ‘Muriel’ (Belcher – the Club’s presiding muse and owner – ‘continues’) was characteristically important. Yet the Colony Club like all things was actually a product of specific history followed by a strange stagnation in civic ethics. It was made possible because of a First-World-war state intervention into activities thought, in The Defence of the Realm Act 1914, to weaken national morale, such as day-time consumption of alcohol. As well as criminalising various other, often trivial, activities, the day would be regulated to stop the consumption of alcohol except in restricted time periods (noon–3pm and 6:30pm–9:30pm). However, the requirement for a gap in the sale of alcohol on public premises that covered afternoons was to remain in England until the Licensing Act 1988. These are the ‘ghastly English laws, you can’t have a drink, can’t do anything’ that opened up invitations to that ‘awful Colony room’ to various persons by Francis Bacon.[4]

Clubs, open only to private members filled that gap in London and there were many of these. For Bacon however it was less a members’ club than a room in a house, whose presiding angel, whom he called ‘Mother’ was Muriel Belcher. A place where, since everyone had to have nicknames (Coffield says in the Art Club interview that was because Muriel had a terrible memory for names) Bacon was welcomed in by her as ‘Daughter’.[5] Coffield also tells us in that same interview that there were at least 500 afternoon drinking clubs in the Borough of Westminster alone during the Colony Club’s lifetime.[6]

However the special and specific nature of The Colony Club was fostered perhaps by its place on the edge of other conventions and norms than the law, although those definitely included the law. Coffield again, in the same interview refers to post second World War Soho as a ‘square mile of vice’, considered at the time as the most illegal areas of Europe, associated with the activities of criminal gangs, prostitutes and ‘queers’.[7] The latter term was a contemporary one and, though for some it was interchangeable with the medicalised category, ‘homosexual’, does not describe very strictly the queer nature nor sexuality of Colony Club members. These were rather people who define themselves against any range of extant social norms, even those that defended the realm by licencing laws, that for some included sex-and-gender-norms. Even class norms were blurred and the Colony included those who equally rebelled against social norms from a position of class privilege, including Princess Margaret, the Queen’s sister, and bevies of aristocrats who hated the imposition of bourgeois sumptuary laws, or indeed other non-legal socialised mores. Such norm breaking characterised the reputation of Soho.

Queerness, in the sense of behaviour and self-presentation that was outside societal norms (and sometimes laws that impinged on personal lives) is I think a better definition of the milieu than associations with criminality sometimes evoked to characterise Soho. One of the glories of the management of the Colony is that it resisted absorption into the heart of criminal gang culture, however much criminal gang-culture remained active on its margins. This was despite the close association of both Bacon and Lucian Freud to those gangs. Belcher and her acolyte, Ian Board, resisted even the Krays, who were inclined anyway to be rather more normative in their public speech and behaviour than was the case in the lives of Colony members.[8]

More important was the association between deviation from norms and art, although even the norms of established art became the enemy of the that group. Of course established art itself returned from the prurient modernist preference for abstract non-figurative art, represented from 1939 by Clement Greenberg in the USA, that had dominated it in a later phase of the colony with the membership of Damien Hurst and others in the 1990s. The fascination with a life made up entirely free of either prescribed direction seems to be the aetiological constant in the disease Coffield calls ‘Sohoitis’; wherein a preference for a life that is merely lived in the precincts of Soho’s tightly contained (geographically) life-diversity drained artists of the need to define or orientate themselves within the world of common norms and conventions.[9]

The most important rule of the Colony was that members never ‘bored’ each other. It meant, say witnesses cited by Coffield, that they never spoke about their work, even if that work was ‘being an artist’. The artists who attended the Colony were largely from interested in representing figures taken from ‘life’, although in order for that take on ‘life’ to be seen truly all those artists needed to radically ‘queer’ their visions. This would be true of the loose group known as the ‘School of London’ as for later figurative artists, even in the belated return to Establishment status of Later-period Colony members such as Damien Hirst and Tracey Emin.

During the 1940s and 1950s, figurative art never established a defence of itself in the theory of art. Perhaps this is why it felt forgotten even in its own life-time. People even more marginal artists such as John Minton (whose suicide is sometimes attributed to his failure to matter to those others who appeared to be creating the history of contemporary art) and Keith Vaughan were so in part because their art could only fail to sell or catch interest in the way mainstream artists did, however large the minorities who supported them. Francis Bacon (like Lucian Freud too) was antagonistic to making even the slightest apologia or defence of his art that would truly have made him seem their leader. This is so much the case I think that we fail to see a group as representative of continuing figurative art in England in this period. I would argue that, were we to do so, we would see a strong continuing link between European traditions (like Cubism, Neo-Romanticism, and Surrealism as the second two of these are described in James Thrall Soby’s After Picasso) of figuration that always could have challenged the hegemony of American (USA) abstract modernism.

Instead we are left with a sense of a loose collection of British figurative artists that are far too often read through their own psychological differences to social norms than as would-be inventors of a new humanity. The latter view would make much more sense if we took into account the fact that the Colony Club included Isabel Rawsthorne as a member and that she introduced to it (in 1965 when he visited the Tate retrospective of his work) her friend/lover Giacometti.[10] The latter sometimes does gets the privilege of being the representative of a new queered vision of figurative humanity. Personally, I mourn this loss to our attempts to make sense of that British art and artists who challenged the more arid paths trod by modernist abstract art at a time when it might have made a difference. It would have also helped us see Francis Bacon as a more central figure in artistic and intellectual traditions rather than as an eccentric and marginal figure, explicable mainly through his own anomie. Of course my contention that what held the figurative tradition together was the queerness of a now Godless humanity, remains entirely subjective but it seems to me to be the tacit message of many words spilled on the figurative art of the period. Nowhere however, will I seek to fully argue this generalisation.

Instead Bacon has been offered either to the maw of academic art history as a phenomenon to be explicated by its methods of ‘rational’ enquiry when not ‘psychologised’ and entirely reduced to a set of personal oddities. Hence, I rather admire Coffield’s book as a means of both challenging the hold of academic discourse on Bacon. In the Arts Club interview Coffield says explicitly that books on Bacon are seem, ‘all written from the point of view of the academic’, and implies that his work not only does not seek that status. It instead, he goes on to suggest, insists (about Colony Club members) that it is ‘important to hear their voices’.[11] And herein lies a conundrum about the method of the book.

For although Coffield tells us the book is based on interviews with members inherited from Michael Wojas and others done by himself, he does not explain how those interviews are collated so that the voices comment on each other, giving ‘different opinions of one event’ in the case of many events.[12] The book reads like a transcript of a group conversation where voices take many roles – some of which, including his own, act to connect the narrative or further explicate its details. I can find no information that helps us know how Coffield arrived at the form – like that of a focus group. I therefore assume it was a deliberate formal and, in my view, aesthetic strategy. In such a work, we cannot rely on the authority of the quotations nor can we locate them in a specific time or place. Rather they are the conversations that the participants would have had had they actually been in the same room as each other when the words were gathered in by Coffield.

Hence, I am claiming that this book is a work of art made by Coffield based on attempting to establish an examination of the meaning of the group of humanity that is his subject. This includes artists of different kinds (performance musicians, visual artists, writers, photographers and film-makers) as well as the consummate artist that is the social impresario. Examples of the latter are legion: the ‘managers’ of the Colony (Muriel Belcher, Ian Board, and Michael Wojas) being the obvious ones but including those who acted as less formal ‘hostesses’, bringing fellow-drinkers to the club, such as Francis Bacon who in his early days was paid in this role and later figures like John Deakin and Rawsthorne. Contributing to this is a cast of characters named largely by their nicknames (with exceptions such as George Melly and Barry Humphries) such as ‘Foreskin’, ‘Maid Marion’ and ‘Dick Whittington’. Sometimes these characters act as a chorus descanting on a theme, such as ‘death’ in Chapter 8, ‘Death in Bohemia’. Yet within this chapter some characters appear to argue with each other as if situated together in real time and space (as Daniel Farson and Bacon do with regard to modern art in general and Gilbert and George in particular). They still descant like a Greek tragedy’s chorus on the nature of ‘art’ and its troubled relationship with ‘a realisation that there is the grave coming up, closer and closer, closer and closer …’.[13]

If we further question the method here, we note that the quotation at the end of the last paragraph apparently cites Bacon speaking about life, art and death to Daniel Farson. Yet the ‘conversation’ if it is such is interrupted by Coffield acting both as a narrator and a person able to explicate further Bacon’s view of death and connecting it to the facts of Bacon’s actual death: ‘not so much a death as a disappearance. Just as he’d wanted’.[14] In the talk that follows Francis can no longer be a participant in the scene because the participants focus on the absurdities that surrounded the ‘wake-cum-party’ that followed, for two days, Bacon’s funeral. As Twiggy (Michael Peel, a fat man who sold computers to banks (who was therefore ironically named) summarises it is an event especial to Soho’s take on human life:

The wonderful thing about Soho was when someone died, people just turned up; there was no official wake, it just happened. We treated death as an imposter, since no one had a lifestyle conducive to longevity. … The Colony was absolutely rammed. Ian [Board] hoped they wouldn’t make a fuss about Francis’ funeral since his idea of a church service was to ‘dispense with the normal ceremony and do something strange with an alter candle’. I was in gales of laughter.[15]

In my view this is fulfilling art that merely apes other genres such as biographical interviews, journalism and/or biography and social history. It is about creating out of the Colony the source of artistic meaning in which events are not interpreted but seen, from numerous perspectives, and queered by their multiple irreverent and contradictory representation in different minds approaching the event with different agendas.

In my view Coffield takes biography into another discursive realm, that of self-conscious art. This is more than Coffield himself claims for the book by others, and certainly more than other commentators who see it as kind of collected commonplace book holding mainly gossip. Multi-disciplinary arts, such as all those that appear in this book, produce images of humanity gathered across specific sense perspectives and their appropriate media– including journalism, photography, music (including pop and rock), social organisation and writing. The Art Club launch of the book hints at its artistic strategies by comparison between Coffield’s contribution, which is reserved about its formal innovation, and the analogies for it provided by other speakers – who speak specifically as artists representing the Colony of which they were part as ART.

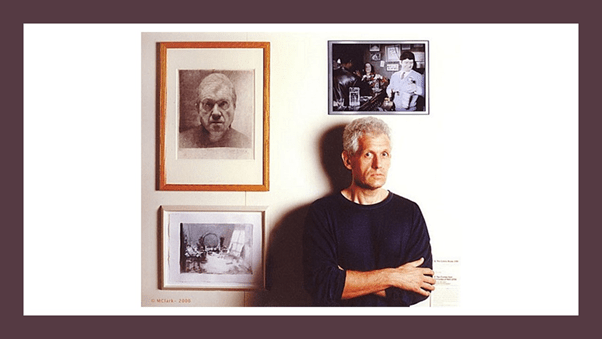

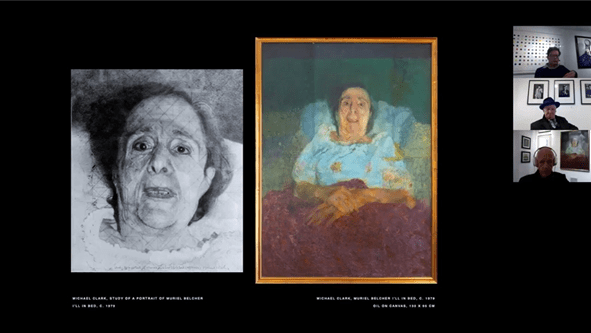

I will concentrate on the contribution by Michael Clark, whose publicity photo below mixes photographs taken of the Colony with art that combines drawn visual art and photographic messages. Not least in the portrait of Bacon, drawn from photographic plates but morphed in ways that present Bacon as a ‘lost leader’. For instance Clark omits the left ear in honour of Bacon’s view of Van Gogh as a ‘wounded healer’.[16] Bacon wears a choker based on conversations between Clark and Bacon in which the latter identified his fantasies around death with fantasies of asphyxiation, possibly in a sexual act OR cyanide poisoning. The picture illustrates, says Clark, Bacon and the Colony Club belief in making art of: ‘lies, if you like, but lies that are more literal than truth’.[17]

He sits for his Art Club talk below in front of his painting, itself based on a photograph (for which both states are shown in the film), named ‘Muriel with Daughter on Her Mind’. Lying on her putative death-bed, Bacon’s own death is what Muriel pre-figures, a death entirely subservient to an art that may not matter other than as a relation between human beings.

I have no certainty about my own beliefs about this book and what it might be doing but I do very strongly feel that it matters as a document of a lost humanity. Look at the photograph with which I end. Those figures may seem to celebrate their continuing life on the 25th anniversary of the Club in 1972 but behind them all, hiding almost, is Bacon (at the very back on the viewer’s right) refusing to give such pretence credibility. Nothing would be the same. There were temporary revivals – such as in the 1990s when Joshua Compston opened up the club to members like Tracey Emin and Gavin Turk, but it was clear that nothing would ‘always be the same’ as in the land of the Lotos-Eaters. In 1988 the Licencing Law reform opened pubs in the afternoon and in the 1990s, despite the flush of Young British Artists arriving, it ‘was considered a bit old fogey-ish to go to a drinking club’.[18]

So I end with this attempt to point to the significance of an ethos of queered humanity – finding meaning out of lack of direction. Perhaps it was always doomed from the start since things in the club only ever ‘seem’d’ (with Tennyson’s Lotos-Eaters) ‘the same’ but were not. I have failed to argue the point and this remains a speculative piece entirely with lots of generalised points that need more thought but let’s work in Ian Board’s mode: “Why Spoil a good story for the sake of accuracy?”[19] Let’s not!

Steve

[1] Daniel Farson cited Coffield (2020a: 27)

[2] Darren Coffield (2020b) cited in Jennings, C. (2020) in ’Interview: Darren Coffield on Tales from the Colony Room: Soho’s Lost Bohemia Apr 22, 2020’ in The London Magazine Available at: https://www.thelondonmagazine.org/interview-darren-coffield-on-tales-from-the-colony-room-sohos-lost-bohemia/

[3] Alfred Tennyson (from stanza 3) The Lotos Eaters, first published in 1832 bur revised in 1842. Available at: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45364/the-lotos-eaters

[4] Bacon cited (without specific date or context) Coffield (2020a: xv).

[5] Coffield cited In a conversational interview organised by the Arts Club London in 2020 to coincide with the publication of his book and a companion exhibition held at the Dellasposa Gallery in London from 15th September and 20th December (Coronavirus lockdowns excepted). Available at: https://www.dellasposa.com/ko/video/9/ .

[6] Coffield (no specific dates or context otherwise given) cited ibid.

[7] ibid.

[8] The Kray twins were on the Colony’s margins (see ‘Maid Marion’ [David Marrion] cited Coffield 2020a: 183) . They abhorred swearing in the company of women (ibid : 46)). Yet swearing by and about any or no gender category was a qualification for entry and acceptance at the Colony. Muriel christened new members, like Tony Tooth of the Tooth Art Gallery, under the name of ‘common little cunt’ (ibid: 4) with impunity. Colony members who had ‘affairs’ with Ronnie Kray, like Teddy Smith, were in grave danger (ibid: 183).

[9] Coffield (2020b) op.cit.

[10] Coffield op. cit. (2020a: 219)

[11] Coffield (2020b) op.cit.

[12] ibid.

[13] Coffield op. cit. (2020a: 253)

[14] ibid.

[15] ibid: 255

[16] Clark cited in Coffield (2020b) op.cit.

[17] ibid.

[18] Coffield (2020a: 250)

[19] ibid: 349

5 thoughts on “‘The club world is a shifting one. A club has its moment, and fades; people pass by or pass on; … Muriel is the exception – she continues’. Learning about the passage of time and persons in Darren Coffield’s (2020) ‘Tales from the Colony Room: London’s Lost Bohemia’”