On Paul Cartledge’s (2020) Thebes: The Forgotten City of Ancient Greece London, Picador. Reflecting again on why and how and to what effect certain versions of cultural history get lost or dispersed.

The cover

A little time ago I became fascinated by Judith Herrin’s 2020 book on the Italian city of Ravenna. I wrote a blog (click on the link to read it) that derived from a fascination with one sentence from the book. This sentence was: ‘There is a great deal of losing and forgetting about Ravenna as well as physical dismantling, which is also a form of forgetting’.[1] This is a wonderful sentence for a historian, who necessarily delves into phenomena whose physical remains are either or both lost or forgotten, often by their violent and ruthless dismantling. It is particularly true of civilisations defeated by those who succeeded them and had an interest in misrepresenting them – as with the Byzantine Roman-Greek Empire and its western representatives explored by Herrin.

When historians deal with the history of periods we call Classical or pre-Classical (whether of Greece or Rome), Herrin’s sentence is even more applicable. The reputation of some historians are built entirely on the uncovering of often forgotten histories from traces of partially or totally lost evidence of cities oft dismantled. Paul Cartledge is known primarily as the historian of ancient Sparta, a civilisation largely known from the records of its victors and successors, such that even the admiration in which they held it may be as compacted with myth as evidence-based hypotheses. This is more the case when, as with Sparta the literary evidence is ‘spartan’ in every sense of our modern use of the word. This is a civilisation that did not record itself in much writing that was likely to survive.

The case with Thebes is similar, although Thebes was a city rich in myth and the birthplace of scribes of many kinds. There may even, as Cartledge acknowledges, be a fragment of truth in the myth that Cadmus, a figure who hails in some versions from the Phoenician city of Tyre, not only founded Ancient Thebes but also the Greek alphabet (known as ‘Cadmean letters’).[2] But Cartledge shows that there is a bias against civilisations like Sparta and Thebes. In part it is because we are trained to seeing the cradle of civilisation in Classical civilizations – those in which arts much nearer to the modern existed and have survived. There is a problem with civilizations whose high-points were probably achieved much earlier and in that time we are used to calling the Archaic period. It is one of the problems of periodization and the labelling of periods that they sometimes carry assumptions he describes as ‘a nominal trap’.[3]

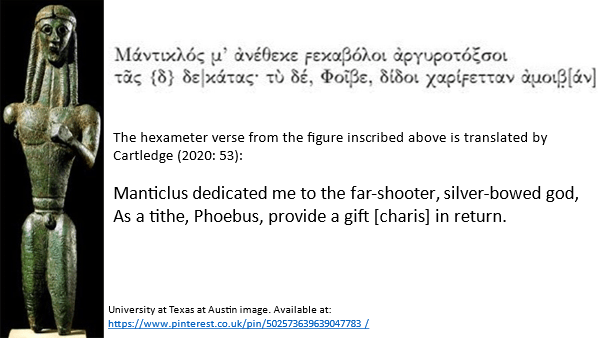

This ‘nominal trap’ carries, Cartledge argues, assumptions and value judgements. The term ‘Archaic’ casts some degree of preference to successor ‘Classical’ civilizations and to suggest imperfection and incompletion. Yet the flowering of Spartan culture was in Archaic not the ‘Classical’ period and Theban strength probably also emerged most strongly in this period as one of the leaders of the geographical area (or ethnos, since the geographical assumption was based on distinctions between peoples) we call Boeotia and may already have federated itself as lead, or co-lead, in that area.[4] Art from that period includes representations of Apollo marked with hexameter verse in readable Greek characters.[5]

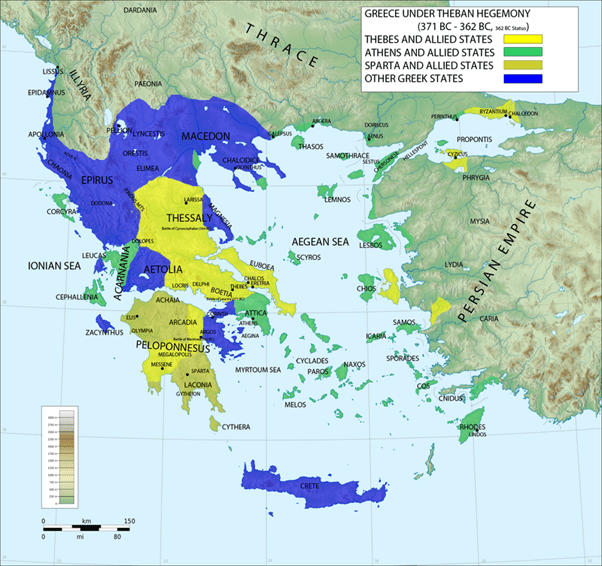

There are clearly understandable reasons why the Archaic Period flowering of Theban culture is ill known except in the myths of the ancient kings that in semi-fiction (perhaps) preceded it. However, there is less reason that modern popular history of the Classical period ignores a second period of Theban near hegemony. Cartledge deals with this in Chapter 9 (‘Theban Heyday: City of Epaminondas and Pelopidas’).[6] This heyday can be guessed at by considering the historical geography of Greece during it in the figure below.

Impressive though this is in showing Theban greatness, it is probably still felt that Thebes merely temporarily filled a gap after the relative decline of Sparta and Athens (the map is only true of 11 years of Greek history for instance). However, Cartledge even makes our relative ignorance of the Theban ‘heyday’ less forgivable in that he points out that Sir Walter Raleigh in his 1614 History of the World said Epaminondas was ‘the worthiest man that ever was bred in that nation of Greece’.[7] About the latter we know very little.[8] Yet Thebes was considered significant enough for his father, Philip of Macedon, not to spare the city’s from the humiliation of becoming a Macedonian garrison as he spared (relatively) Athens after his victory at the Battle of Chaeronea in 338 BCE. This was not just because then Thebes, so late in its history, was now a democracy on the Athenian model, although its oligarchs conspired in the fall of Theban democracy.[9] In 335, Alexander III (not yet the Great) razed its fortifications and annihilated Thebes, selling thousands of Thebans into slavery when it had revolted against the severity of the now dead Philip’s punishment. Again Athens survived.

Cartledge however does try to make good the bias of the contemporary historians whose bias to Athens marks their histories. The latter is more true of Thucydides than Herodotus and Cartledge devotes a whole 50 page chapter to re-telling Thucydides narrative of the Peloponnesian and Corinthian Wars with a sense of fairness to the significance of Thebes role.[10] Though this is obviously really important, I found this the least compelling part of the book but that is quite unfair to it, since Cartledge’s point is that Thebes was forgotten in part because of such bias in the extant historical accounts and because later historians have over-venerated Thucydides accuracy. And much of this book makes a good case for showing that issues of epistemology and methodology in history can still form a strong and vital role in popular histories, especially in its Part 1 on ‘Pre-History’.[11] The examination of evidence is most fascinating to me when it deals with using myth and literary versions of myth as historical evidence. This is important because Thebes is known to many (and I include myself once before I read Edith Hall), when it is known at all, as the setting mainly of very great Attic tragedies.

The myths behind those tragedies were endlessly recycled and revised, and this is so even in those that remain to us. They focused on the family or dynasty related to, or supposed to have sprung, like his grandson Oedipus, from the loins of Labdacus (but ultimately traceable to Cadmus, Labdacus’ grandfather). However, Thebes was never a neutral setting in which to place a drama. Attic Athens was, for much of its Classical history and pre-history, considered to be a major rival to the power, and the political development of Boeotian Thebes. Major plays by tragedians working in Attica or under its influence are set in Thebes but whose narrative mostly aims to forecast the pre-eminence of Attic Athens over the regional hegemons of other states, just as Aeschylus’ Oresteia marks future Athenian predominance over its setting in Argos or Mycenae.[12]

Although these city-states and the loose regional federations to which they belonged identified at some level as Hellenes, rather than Greek because this was a Roman reduction of the population, their jurisdiction and political systems varied enormously. Moreover, although their political systems varied, expressing the contests of different internal interests, it was of use to Athens to typecast the oligarchic and aristocratic bent of Theban leadership systems as extremes of their kind, based, for instance on ruling aristocratic families. They symbolically represented these persons and families by the myths of kings and their dynasties revered in the Archaic period.

Cartledge, for instance, cites a paeon of praise for Athenian democracy delivered to a Theban monarchical apologist from Euripides’ (dated 423 BCE) The Suppliant Women (where Theseus of Athens saves the day). This must have been stirring as Cartledge says for a fifth century Athenian aware that their city-state and its allies were at war not only with Sparta but their Theban allies. Cartledge quotes John Davie’s ‘sober and accurate prose translation’.[13] For that reason, I will go for one in probably less ‘accurate’ verse in order to bring in more of the kind of argument you might expect between representations of Thebes and Athens: the turning of politics into poetry (and vice versa) being a theme I have to return to. The herald from Thebes defends a politics led by people of appropriate birth and family, to receive short shrift from, in Cartledge’s words, Theseus’ ‘magnificent declaration of democratic, ideological intent’.[14]

THEBAN HERALD:

How can a mindless herd rule a city properly? It can’t!

…

And then, it’s a bitter thing to see, men of base birth enter a city, make some fine speeches to the people and then with those speeches become even more prominent than the nobles!

Theseus:

…

All right then, my man. You’ve started this debate so let’s perform it. You said your piece now hear mine: There’s no heavier burden for a city to bear than a monarch.

To begin with, a city like that has no laws that are equal to all of its citizens. It can’t. It is a place where one man holds all the laws of the city in his own hands and dictates them as he wants. What then of equality? (line 430)

Written laws, however, give this equal treatment to all, rich and poor. If a poor man is insulted by a rich one, then that poor man has every right to use the same words against that rich man.

…

The essence of freedom is in these words: “He who has a good idea for the city let him bring it before its citizens.”

You see? This way, he who has a good idea for the city will gain praise. The others are free to stay silent. (line 440)

Is there a greater exhibition of fairness than this?[15]

In British education, in the 1960s as I experienced it, dramatic tragedy was largely taught ideologically in schools. Its themes were spoken about as those universal to human life and to focus on the individual character of persons, thought to be an expression of an unchanging human nature. I still remember the shock then in reading in Aeschylus’ The Suppliants, a discussion of the relative merits of public and private housing with regard to migrants. Attic Tragedy was clearly a sophisticated genre that was not reducible to supposed ‘human universals’ but necessitated we look at contemporary political debates, just as, we ought to also argue, this is necessary in the much more derivative and schooled examples of English Elizabethan and Jacobean tragedy. The discussion of the conditions of liberty and equality in relation to political systems is intrinsic to both Euripides, in the example above used by Cartledge, as is any consideration of the supposedly unchanging universals of human nature, indeed more so.

What Cartledge has long insisted upon is that Attic tragedy was an ideological weapon in which Thebes was not meant to represent neither entirely an entity in political geography and history but also an abstract condition of human bondage to an aristocratic ideal that could only bind the ‘freer’ minds and hearts of Attic citizens. In a sense, Thebes was always an enemy within the Attic state ready to return it to the conditions of oligarchic or even monarchical rule, where the few held power over the many, which the many themselves legitimated by their deference to that power. He shows how Thebes was misrepresented by its enemies in the interests of its own democratic ideological constructions. This makes the book of inestimable value both in understanding the difference between living in history and the records which supplant and reinterpret it. There is therefore much recourse to trying to see the literature of the period through the reception of it by its original and intended audiences.

This latter project is always problematic because of the assumptions we make both about how intention is structured into art and how the codes for this are received by audiences we cannot really assume that we know this other than by inference from other historical factors. Mainly this is done in a very nuanced way but sometimes it is not. An example of the latter is found where Cartledge reconstructs the original Athenian audience reception of the role of the God Dionysus in their classic drama. Dionysus, or Bacchus, was for Athenians the presiding divine symbol of the theatre of makeshift and play but they took him seriously, as they did the theatrical festivals in which he is celebrated for them. Yet Dionysus is also a God very much equated with the tribulations of the Theban heirs of Cadmus. Hence he imagines that Athenians viewed the awful ritual intra-familial murders recounted in Euripides’ The Bacchae (Queen Agave dismembers her son, the prince, Pentheus, as part of her participation in an all-female frenzied version of a Bacchic rite) first as narrative, second as something characteristic of Theban ‘otherness’.

… how could it be good to contemplate the Dionysus/Bacchus of the Bacchae – except so as to thank heaven that good respectable Athenian women (citizen, wives, daughters and sisters), and regular Dionysiac cult worship, were not at all like that. (Cartledge’s emphasis).[16]

No doubt, at any period of history, there would be such stereotyped smug reactions based on prejudicial assumption of the superiority of the norms of one’s own culture over those of one we are socially permitted to despise by that culture. However, I do not think it is very unlikely that this represented the view of everyone in that culture or even the majority. The truth is we cannot know, as Cartledge, of course, admits.

In other instances Cartledge does not take the analysis of Thebes as the ‘other’ in Athenian society far enough for me, and thus reduces its conscious political radicalism in my opinion. And it has always seemed to me that in Thebes as it is represented to Athenian audiences, we see a concentration on the family and the legitimacy of the patrilineal family relationships as the sole legitimate model of political power. In Theban tragedies, as written by and for Athens, the root of political corruption lies in the uncertainties and secrets to which transmission of power occurs in families that endure over time. This is surely the set of feelings at the base of how Athenians responded to Pentheus’s fate – that family with generated both his life and entitlement is also the means of his destruction by virtue of its basis in irrational non-consensual relationships.

For familial inheritance of power in aristocratic or oligarchic systems is precisely the object against which Athenian democracy sets its ideological cap. Tragedies examine great houses and families in the context of political debates that often concentrated on the failings of the political institution the Greeks knew as the oikos (οἶκος in Ancient Greek) and which might be translated as the household and its dependencies. For authority in such a system depends entirely on principles of inheritance between parents and children and not least how true parental transmission from the father was legitimated. In Cleisthenes’s reforms, the invention of the basic unit of the deme (δῆμος – demos – in Ancient Greek) created a quite different relationship between who, among its members, held authority, at least in theory and would have created a debate in which family, as a political unit – especially in the transmission of power relations – became public themes in political debate. For Cleisthenes’ demes even reformulated the relations of persons, land and power (the very roots of the power of the oikos).

It was of great pertinence then in Athens to discuss the principles of governance that sustained great aristocratic families, and the relation of these to public welfare. As Cartledge shows the plague in Thebes in Oedipus Tyrannus must have resonated for its audience with a plague suffered in Athens in 430/429 BCE and being experienced by its original audience and ‘prompted them to start drawing comparisons and analogies’.[17] This may have been an element in their response to the power of Pericles (from the ‘accursed’ aristocratic Alcmaeonid family) as Cartledge says but more important to me are the ways rule by family is being systematically undermined, since it is possible (the play shows – admittedly under extreme circumstances) for family relationships to become entirely subverted, and the rule of public law and governance be therefore undermined – which is at the heart of the Labdacid family tragedies.

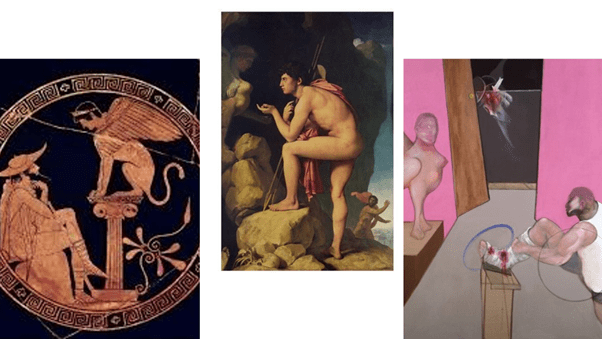

Reception theory is dominant in the teaching of Classics in our day, wherein how classical texts are read at different points of history is the key object of knowledge. In this theory a reception should not be confused with the play’s intentional or ‘original’ meaning (after all the latter is only a reception too). Cartledge thus distances himself from Sigmund Freud’s reading of the Oedipus myth, largely based on Sophocles Oedipus Tyrannus, wherein was collateral cultural evidence of what he interpreted as a universal ‘fact’ that he was to call the Oedipus Complex. However, it seems to me that Cartledge’s rather edgy ironies against Freud lead only to what are, after all, a commonplace contemporary means of undermining classical Freudian psychodynamics. Freudian psychoanalytic tenets are thus dismissed or marginalised by calling them ‘psychologizing’?[18] But this seems to an empty response to the way in which even partial readings may still refer us to something intrinsic across different cultural-historical receptions of the play. We can look at this in the examples below from different periods of visual art.

We can talk about each of these as a reception of the myth because they interpret it differently in line with issues known to them. but receptions play upon each other. Freud venerated the Ingres painting, The Bacon is explicitly labelled ‘after Ingres’). Bacon knew his Fred though Ingres could not. But there is other commonality here other than overlap which has to do with more than ‘reception’. each emphasises a mystery or darkness about the sphinx, although Bacon delegates that darkness behind a door opening onto a dark interior space in which a strange figure lurks, sometimes said to be a Fury. Though, Bacon’s sphinx looks like a reproduction cast, its face bears the secret of other faces that merge into or come out of each other, whilst the Swellfoot (what Oedipus means and the name given to Oedipus in Shelley’s political ‘Swellfoot the Tyrant’) wounded foot seems to belong to George Dyer, Bacon’s dead working class lover. We are in each questioning the very relationships that are discoursed upon. And I think this is true of the 5th century example as well. In each the Oedipus figure is overconfident of his own knowledge and will therefore be brought low. Perhaps the 5th century example is itself more mysterious than the others since we see Oedipus as a traveller and at rest. And though he is situated beneath the sphinx, he still seems to command the space. Versions of these ideas appear in all these images. And most receptions too have such commonalty in a myth or play to call upon.

In dealing with reception, critics may have to justify their selections and Cartledge is, I would argue, as open to this as other users of this favourite approach of disciplines in the Classics as currently constituted. For me, one he does not use, has been a great favourite of my own, since it feeds from other receptions, is a clear and open revision of the play. It makes the Theban trilogy of Sophocles for instance a ‘real’ trilogy (rather than recognising three different plays from three different Oedipus trilogies) by reconfiguring them as three acts of one shorter opera: the English National Opera’s 2014 version of Thebans: Opera in Three Acts. With music by Julian Anderson, Frank McGuiness’s libretto points to the superiority I believe Sophocles himself saw in the rule of public law above those of family and dynastic kings, a point still needing to be made in 2014 England, where the seeds of populist authority that plague our current politics were already evident. The play used its music, costumes to focus both political and near psychodynamic themes. Moreover, it utilised the bias to Athenian law in the play as a means of by-passing those who damn others by invoking their ‘otherness’. That is intrinsic to all receptions – since even Freud felt that the tension of the play sought release from self-condemning moral systems that make up the ego in his passages on the play in the 1899 The Interpretation of Dreams.

Release her, Creon.

This place reveres justice,

This city acts according to its laws.[19]

That law defeats prejudice is a potent force in The Athenian concern with Thebes. Unfair to historical Thebes, Cartledge convinces me it is, but he does not convince me (yet) of the fact that these great drama still speak to us in some ways in the same ways as they did to audiences in Classical Athens.

But this is a very enjoyable book and stimulates readers.

Steve

[1] Judith Herrin (2020: 387) Ravenna: Capital of Empire, Crucible of Europe London, Allen Lane, Penguin, Random House.

[2] Cartledge (2020: 23).

[3] ibid: 47

[4] ibid: 48

[5] ibid: 53

[6] ibid: 184ff.

[7] cited ibid: 185

[8] ibid: 186

[9] ibid: 230

[10] Ch. 8, ibid: 132 – 183

[11] ibid: 3 – 46

[12] Dramatists were not beyond treating such foreign cities from the Archaic period, despite the fact that they are entirely different, as one place based on the name of the extant city in the period in which they wrote rather than of which they wrote. In this case, of course, it was Argos.

[13] ibid: 117

[14] ibid: 116

[15] Euripides, The Suppliant Women’ Translated by George Theodoridis © Copyright 2010, all rights reserved – Bacchicstage Available at: https://www.poetryintranslation.com/PITBR/Greek/SuppliantWomen.php

[16] ibid: 121

[17] ibid: 124f.

[18] ibid: 259

[19] Theseus (in act 3) of McGuiness, F. after Sophocles (2014: 34) Thebans: Opera in three Acts: Libretto London, Faber Music.