Reflecting on art, masculinity, pornography and sexual violence. Can these ideas be separated? Examining Sebastian Munôz’s film The Prince (El Principe). Note that this film is rated suitable only for people over the age of 18 because it contains sexual violence, strong sex, nudity and ‘gory injury details’. Do not read this if you are offended by references to sexual or violent content in the film.

Click for Trailer (age check on video)

Click for Source of all photographs below

Click for Cast / Characters List

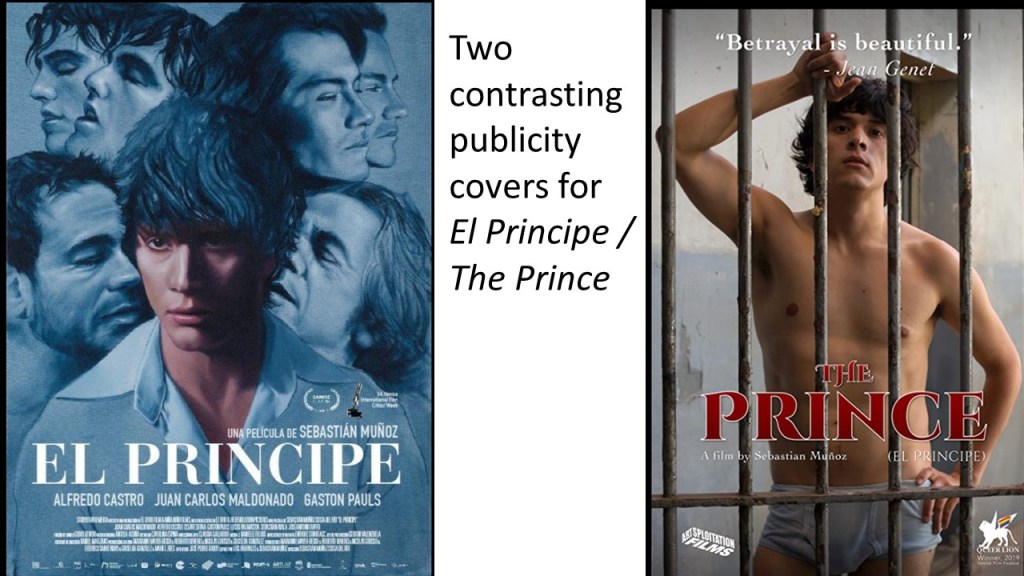

Liking a film like The Prince calls for explanation from many points of view that is often assumed by the comparisons made between it and other artists. These include Jean Genet, Derek Jarman and Rainer Werner Fassbinder and whilst the artistic links are there, these names also serve as codes for artists who put homoeroticism and other queered sexual relationships at the centre of both their treatments of stories of experience and their concepts of the queer complexity of our culture’s interest in beauty and especially soiled beauty.

Likewise these artists concentrate on men and, in doing so, imply the necessity of the role of both unequal power and violence. Hence the review, apparently from Art House Street, quoted on my copy of the film: ‘Equally sexy and sordid … will remind you of the movies of Fassbinder and Derek Jarman’. I would like to stay for a while with that word ‘sordid’ and its range of meanings, all of which Munoz form part of the ways Munoz treats the relation of men and their developing and varying sexual experience, where that includes other men either by choice or felt necessity, or sometimes where those motives are extremely mixed. Take the fundamental variations of meaning in the Mirriam-Webster dictionary for instance:

1: marked by baseness or grossness : VILE sordid motives

3: meanly avaricious : COVETOUS

4: of a dull or muddy color (sic.)

The mix here of a word crossing between the materiality of its reference to physical signs of dirt and the association with compromised ethics, whether in business (a ‘sordid deal’), the means of living life or conducting relations with other persons or bodies is important culturally. The film glories in the same passage between meanings at all those levels and, I think queries, any simplistic reading thereof. For the criminals in this prison are complex as the relationships of El Potro (played by the wonderful Alfredo Castro) show throughout. El Potro is translated in the English subtitles as ‘The Stud’ rather than just ‘stallion’, a fair way of translating the animal sexual association of the man. The most sordid of relationships and deals are those between him and Che Pibe (Gastón Pauls) and these involve the symbolic murder of El Porto’s cat, Platon (Plato), a near symbol of the complex hard to categorise mix of the dirty, merely transactional and the ideal in El Porto’s conception of love.

Plato the cat has an important visual and symbolic function in domesticating and idealising the energy of El Potro’s sometimes urgent sexual need. Look, for instance, at the scene above in which the two male lovers from the cell’s top-bunk form a ‘queer or chosen family’, at the centre of which Plato is lovingly cuddled by El Potro as he looks on, almost like a father (pr perhaps a pedagogue from the classical tradition), at Maldonado’s Jaime (Il Principe within the system of prison role names) learning to play the guitar he bought him as a love token. The male lovers here as elsewhere act almost as a chorus to scenes in which animal sexuality is mixed together with both tenderness and loving attention that occur for El Potro in his lower bunk. The play of meanings between visual and symbolic ethical or experiential hierarchies that bring together contrasts throughout the film of cleanliness and dirt (in the shower scenes for instance), upper and lower levels and attitudes to love and sex such that they interpret each other.

The materialisation of the sordid as dirt is a deep symbol moreover elsewhere in the film. Even before his imprisonment and elevation to the titular name El Principe, Jaime’s education into sexuality mixes scenes in which relative status and expression of relationship in and through dirt play as much a role as does sex of any form. For instance, Jaime masturbates as he surreptitiously watches, having sex with a young woman ,the slightly older young man, El Gitano or the Gypsy (Cesare Serra), to whom he is attracted. The scene which follows shows Jaime expressing his consequent sexual frustration in scenes of direct body contact and interplay, sometimes violent but not always, with the earth and mud.

We can be sure that Munôz intended a rich set of interactive meanings here from the scenes in which Jaime first learns the virtue and power of his sexual fascination, to both slight younger boys who look up to Jaime’s sexual ‘maturity’ and older women, in the scenes in which he and younger males bathe in dirty water, giving themselves up afterwards to rolling naked in mud before they urge Jaime o show them how an older boy masturbates and to what immediate physical consequence. The undeleted scenes, should you chance to see them, show even more the play of phallic experience and the sheer joy of being mixed up as a self-identifying group where discrimination of individuals is less important than a common covering of mud and dirt, of which the example below is a much more coy example.

The interest in male sexuality as a learned phenomenon which plays across categories like sex,/gender and age and the power relationships implied in these category differences is extremely subtle in the film. The tendency in synopses of the plot, for instance, to call Jaime a narcissist (contrast this with a film that definitely priorities this mode of exploration of male desire in my review of Steve McQueen’s Shame) is I think profoundly mistaken. Of course exploration of loving self, and identifying the ‘sexual other’ with self, do play a part (this is about the complexity of real life after all) and are made sometimes explicit. The danger of overplaying this element would be however to accuse the film unfairly of falling into stereotyped and oppressive explanations of the queer category people like to call ‘the homosexual’ as someone who never matures into love of a genuine other, that is sometimes associated with naïve psychodynamic aetiologies of homosexuality.

The detail above from the film shows that point (Jaime is in prison and has been adopted by El Potro as a current lover) where Jaime begins to realise the power of how he ‘looks’ to others as a means of gaining his own ends in terms of status and goods (especially a beautiful pibk jacket). But though the character learns to refine that look for the purposes of power and transactional wealth in the prison economy, the film does not I believe explain sexual love and its nuanced versions this way at all, otherwise why invoke Plato who felt that reality as most men see it is a confused mirror reflection in a dark cave.[1]

The film’s famed tendernesses, and the reason it became its year’s Lion Queer Film of the Year, feel to me to argue a very complex aetiology for all loving relationships that in some way are more complex than sexual drive and frustration. As in Wilde’s famous quotation, used by Fassbinder in his film of Genet’s Querrelle of Brest, ‘each man kills the thing he loves’ in Jaime’s case too, supplanting it it with an image of a man’s own powerful and purely phallic sexuality. In his feeling for El Gitano, Jaime felt a need for safety, security and warmth. Hence when El Gitano asks Jaime why he held onto him so tight when on the back of his motorbike his evasive answer is not purely a means of masking sexual interest. Much of this meaning speaks inarticulately through Jaime’s gaze upon El Gitano and the pure joy of bodily proximity in the scenes in which we see them need not be read reductively (see one example, for instance, below).

Here Jaime embraces El Gitano like the wind that hits his face, mirroring, if anything, only the smile which we are shown El Gitano can teach him. This smile has not yet been cashed in for goods or status as it will be in the complex all-male power and desire nexus that is a pron community.

This mercenary exploitation of the look is well conveyed in the still below, where Jaime uses his cigarette to bring attention to his sensual mouth and the torso that will attract and keep attracted the little court in which he is the prince.

But the community which I above called a court in honour of Jaime’s renaming as ‘The Prince’ is a complex group, which produces in this film some absolutely beautiful images of tender togetherness which stop us from seeing this film as primarily a film by the pornographic in male sexuality and should start us in exploring more seriously the nature of male-to-male bonding and the role of sex within those bonds. I think the links to both dirt and baseness are complex ways of exploring what it means to live in a body that must form part of our expressions of affection to each other. Even the clear image of narcissism I looked at above shows Jaime contemplating the powerful sexual self which he tests as a possible object of his own desire through the medium of stains on the surface of the mirror he looks at.

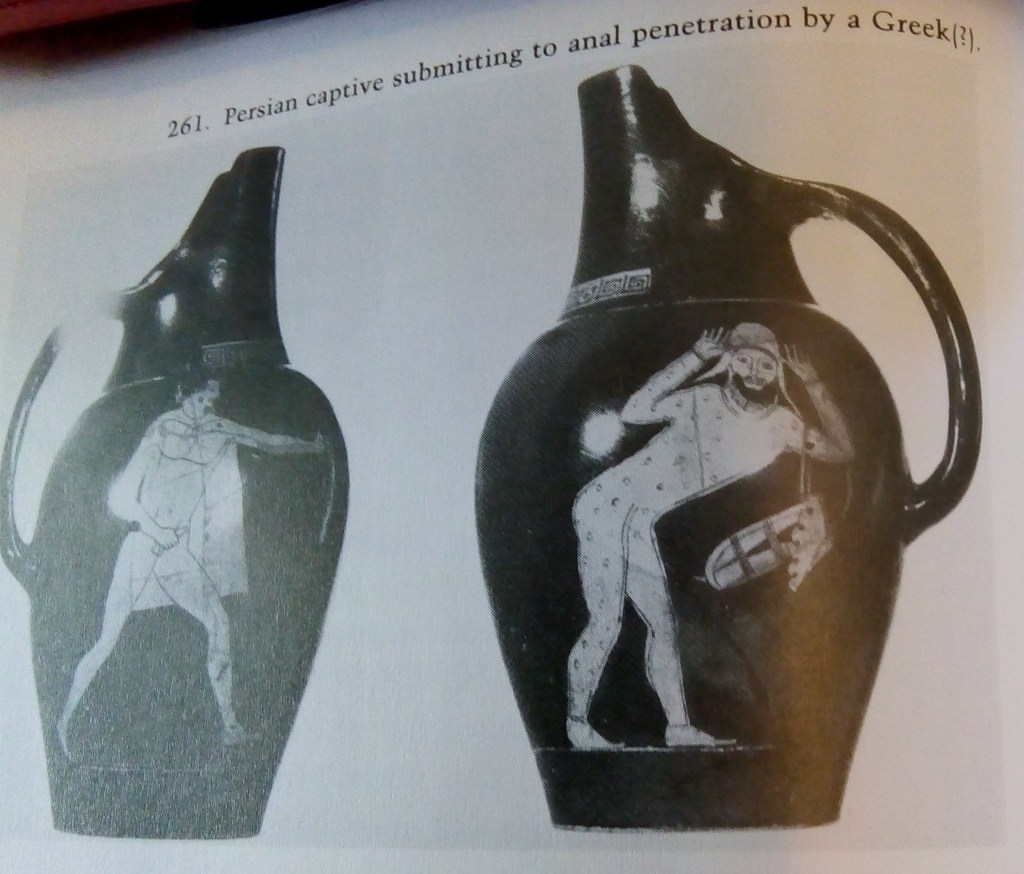

We are used to equating sex and especially male sexual penetration with images of superior power. Even in Ancient Attica, it was enough for Aristophanes to condemn Cleisthenes by referring to him as a ‘wide gaping ass hole’ (in Keul’s translation). Eva Keuls also adduces possible earlier evidence from a red-figure pitcher, which possibly shows the victorious Athenian manhood preparing itself to anally rape a Persian captive of war.[2]

This film uses this ancient image of anal sex to display masculinity adjudged on a scale from those who penetrate and those who are penetrated. The latter are seen not only as humilated but as belittled. Thus when the prison guards wish to humiliate El Potro, they anally rape him using a very large pole on the table in his cell and in front of his cellmates. It is a most vicious scene. But this is more than ‘demeaning and humiliating’ a candidate for an alpha male role.[3] El Potro initiates Jaime as his possession and underling, if also El Pincipe, by a painful penetration on their first meeting. This is how he shows he is boss. But the film also overturns these images of humiliating defeat.

When El Potro’s feelings for his Prince deepen, he unclothes in front of the latter when they are alone in their cell and presents his rear body to Jaime, holding his head against the wall. In the final edition of the film this classic gesture of shame (facing a wall and looking down) marks perhaps another low in the stallion’s sexual career. But we aren’t invited to read this so simply. The scene clearly expresses the deepest love El Potro will ever feel, a kind of sharing that had been missing from Jaime’s initiation as it had been of all the other young beautiful men who had fulfilled this role in the past for him. El Potro has heretofore held on to a heteronormative role in which his young men substituted for a lost wife in the world which he often mentions, just as he nominates less ‘masculine’, if equally violent rivals, like Che Pibe (Oh Boy), ‘fags’, whom Jaime should avoid. This is even more clear in the uncut version of the scene when the position is clearly seen as not an adoption of meere passivity but a sharing of phallic experience. What is happening here is that signs of what constitutes masculinity are being varied and become, as a result, nuanced and enabled to express tender nuances, not just hard, clear-cutand violent singular meaning. A brilliant critic of a first draft of this piece called this a recognition that ‘people just have to live in their own skin’ regardless of any imposed category and in this skin the differences between emotions, sensations, thoughts and postures become complicated.

What else can one say about some of the cell scenes of El Principe but that they show people comfortable in their skin, and indeed their clothing and the spatial setting. Every detail emphasises this delicious sense of security, where concepts of home and prison, according to Gaston Bachelard, come together in the shape of space in which we are all curled up in security. It is a piece where primal space has to do with comfort in living in the folds of one’s own body, those points where bodies touch and wherein we inhabit our clothing. Witness Bachelard on the domestic space engraved in the imagination and the body that means nothing more than itself, a space that is truly lived in and therefore must be safe:

To curl up belongs to the phenomenology of the verb “to inhabit,” and only those who have learned to do so can inhabit with intensity.[4]

The more simple the engraved house the more it fires my imagination as an inhabitant. It does not remain a mere “representation.” Its lines have force and, as a shelter it is fortifying. It asks to be lived in simply with all the security that simplicity gives. (Emphases are Bachelard’s)[5]

Not every reader has the patience to read as intuitively the basic images of the phenomenology of space as does Bachelard. Likewise there will be those who do not respond to the curled bodies that inhabit safe space in this most paradoxical of setting – a place that imprisons those within it. This is so similar to Bachelard’s phenomenological readings which always place safe spaces in an imprisoning and hostile environment:

… if we “listen” to the design of things, we encounter an angle, a trap detains the dreamer:

Mais il ya des angles d’ou l’on ne peut plus sortir

(But there are angles from which one cannot escape.)

Yet even in this prison, there is peace. in these angles and corners, the dreamer would appear to enjoy the repose that divides being and non-being. He is the being of an unreality. Only an event can cast him out. …[6]

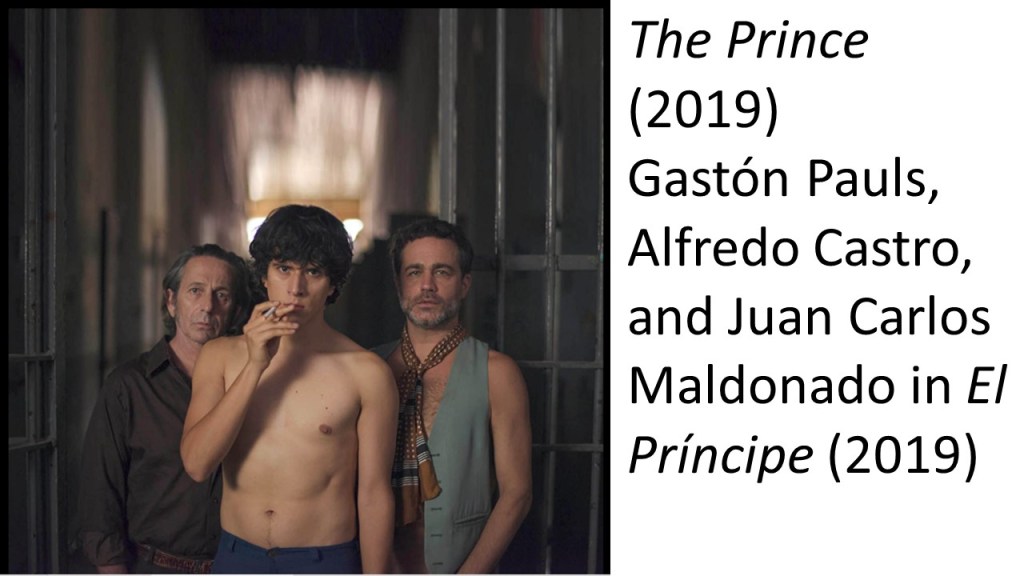

This otherness of peace and the inhabitation of security lies beyond the world of events and it is events that cause insecurity. In this film insecurity is a place where life is a contest involved at least three people. Sexual triangles are the source of disruption and it is in these that persons two of those persons compete for the valued attention of a third. In El Principe masculinity is a concept that becomes troublesome and oppressive only in male sexual triangles, of which the most iconic is between Che Pibe, El Potro and Jaime El Principe. It is this triangle which leads directly to the murder of Plato the cat inhabiting the domestic space I have spoken about and indirectly but inevitably to the death of Che Pibe and El Potro. For this reason I find the publicity photo from the filmmakers below very telling.

Over-reading it may be, but I love the way that the light falling from the left of the photograph helps Jaime and El Potro to inhabit totally lighted space, whilst Che Pibe relates to both the others from the way Jaime’s shadow falls upon, limiting their free space.

And, of course, Jaime becomes El Principe because of another exclusively male sexual triangle between himself, El Gitano and the other man typed, like Che Pibe, as an exclusively gay man, or in El Potro’s terms, fag. He is El Tropical (Daniel Antilivo). Whilst Jaime accepts the attention of the exotically behaved El Tropical including the sexualised camp of his embrace, it is seeing such attention given to his secret beloved, El Gitano, that causes the violence in which he cuts the throat of El Gitano with a broken bottle whilst El Gitano is dancing with El Tropical. And it is this sexual triangle based on an inarticulate but socially demanded masculinity that governs the socialised triangles that leads to his imprisonment and will lead to the death of El Potro.

I am aware I leave this on an idea that might benefit from more articulate examination but I am loathe to do this because my blogs serve mainly my own understandings, or even misunderstandings, of the dynamics of life, and these are served without further words. I apologise if you needed more. Watch the film, read this again and you may feel what both things offer relate to you and you will follow them up. On the other hand, you may not and we never had the basis of a dialogue. Such is life.

Steve

[1] See selections from The Republic, Books 6 and 7 (‘The Divided Line’ & ‘The Allegory of the Cave’) in https://www.utm.edu/staff/jfieser/class/314/03-314-plato.htm

[2] Keuls, E.C.. (1985: 292f.) The Reign of the Phallus: Sexual Politics in Ancient Athens Berkeley etc., University of California Press

[3] ibid.

[4] Bachelard, G. trans. Jolas, M. (2014: p. 21, Location 759) The Poetics of Space (first published 1964) Penguin Books, Kindle ed.

[5] ibid: p. 71, Location 1544

[6] ibid: p. 163, Location 3059 The quotation is from Poèmes à l’autre moi (Poems to My Other Self) by Pierre Albert-Birot.