Photography of Faces: What does ‘fame’ look like in 1960? L. Fritz Gruber (ed.) (1960) FAME: Famous Portraits of Famous People by Famous Photographers London and New York, The Focal Press.

First of all: this blog speaks of a select gallery of images from a book I found in Oxfam at Darlington that largely attempt to speak for themselves in the book itself. The book isn’t just a curious collection, it had a message for its time and hence my interest in writing about them. To understand that message we need, I found as I efected, a little information about the editor, L. Fritz Gruber, a great collector and advocate of the photograph as an art form. Armed with that, we read his introduction to the book, which focuses on the principles of both selection and display of portraits in this lovely book, much more carefully.

The aim of the book, as I shall try to establish in more detail below and Gruber insists in his preface is at least twofold: to establish the credentials of the individual photographer as an exemplum of the ‘psychological penetration and expressive intensity’ of an art. It will therefore both:

- document historical contemporaneity (in the pioneer French photographer Eugène Atget’s terms as well those of a simpler historicism), and;

- communicate rather more universal meaning and emotion creatively[1]

To do both of these things our book and its contents must be placed in two contexts. First, the continua of both the history of art that represented feelings about, and the perceived meaning of what people recognized ‘as narratives or likenesses of their leaders’. Second, a history of how documents became the evidence of history and attitudes about what made certain contemporaries seem as if the represented ‘ the famous, perhaps the great’.[2] Gruber felicitously ends his preface by arguing that even if the passage of time robs documents of their value as living documents, they continue to live as expressive art: ‘these portraits have become documents turned artistic symbols’.

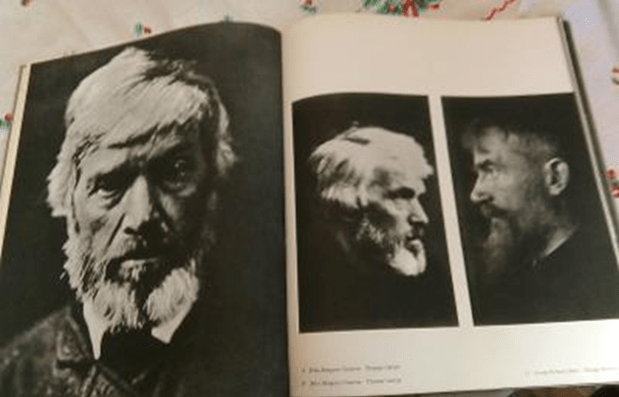

The simplest illustration of this is in an early fold of the book which contrasts the representation of a culture’s belief in the value of its contemporary, Thomas Carlyle (1795-1881), with one still respected (if on the way out by 1960), George Bernard Shaw (1856-1950), a man with a continuing, if perhaps diminishing, historical significance in 1960.

Gruber’s silent aim in this fold of the book appears to me to focus on the concept of the Victorian ‘great man’ (perhaps best described as a ‘sage’). The concept of the Victorian sage was associated with both Carlyle and his most famous photographer, Julia Margaret Cameron. The ‘Famous Man’ genre of the photograph was feted, for instance, by Virginia Woolf, Julia Margaret Cameron’s niece, and Roger Fry in their Victorian Photographs of Famous Men and Fair Women. But they also noted its dated, and sexist (though not by using that word), character as a mindset.[3] Using one’s fame as a photographer to celebrate the fame of others, though established by a privileged and Bohemian intelligentsia , could be understood and accepted in wider society, and this is what writers would indicate by calling that age, ‘Victorian’. It’s a point made by Virginia Woolf in her satirical play Freshwater, which casts doubt on the continuing ‘greatness’ of ‘great’ men such as the poet Tennyson and his beloved but forgotten Arthur Henry Hallam, commemorated to public memory in In Memoriam: ‘What’s Hallam? What’s In Memoriam?’, says the thoroughly modern Mr Craig, a young airman who likes Ellen Terry best in new-fashioned trousers and who lives in unfashionable, to the Victorians, ‘Bloomsbury’.[4]

Even the validity of the great art used to capture ‘great men’ by pioneer photographer Julia Margaret Cameron is questioned, though we know Woolf decorated the right hand side of the hall of her Gordon Square home with photographs by Cameron of Darwin, Tennyson and Browning. In both versions of Freshwater, Cameron’s sagacity as giving a ‘message to her age’ is satirised, but by 1935, in not 1923, her artistic technique is reduced to a kind of trickery:

Mrs J.M. Cameron: And my message to my age is When you want to take a picture Be careful to fix your Lens out of focus?

Mr Cameron: Hocus pocus, hocus pocus, That’s the rhyme to focus. And my message to my age is – Watts – don’t keep marmosets in cages –

John [Craig] and Nell [Ellen Terry]:They’re all cracked – quite cracked – ….[5]

The point I am struggling to make here is, even to modernist Bloomsbury, the Victorian sage, and the ‘great’ man are inappropriate and undemocratic concepts. As I read it, the contrast between the ‘sages’ of different centuries implied in Gruber’s placement is between the established social status of ‘Famous Man’ in Carlyle with the self-fashioning of Shaw by himself as his own photographer as a ‘Sage’ at a time when Sages were no longer the order of the day. Gruber puts them contiguously to emphasise their function as what he calls the first of the Carlyle portraits, ‘a real masterpiece of early portraiture’.[6]

The democratic distaste for the claims of privileged (either by birth, merit or both) individuals to be greater than others was under even more pressure by 1960, when Gruber’s book on ‘Fame’ is published. This tendency was represented to me, as a grammar school boy at the time in the wonderful urgency of Michael Young’s 1958 book, The Rise of the Meritocracy. It is an urgency that Young himself (in 2001) came to regret when Tony Blair embraced the term as a positive of historical progress rather than of the historical continua of an anti-progressive establishment. It comes as no surprise then that Gruber emphasises not the greatness of the Famous subject – man or woman – as Cameron might but the greatness of the art that:

… not only exemplifies fame, but creates it in the first place. … Photographs remain. Photographic portraits are part of the person, will be identified with them, will stand in for them. After the living are gone the camera’s visions of them become their lasting images of identity.[7]

Hence the ‘fame’ involved in examining Gruber’s curation of the photographs in this book is, I think, quite unlike that Woolf quality sees in Mrs Cameron’s photographs. Shaw may have intended fashioning an identity that mirrored that of the Victorian sage of which Carlyle was the primary example. He may have intended such an act ironically as always in this great master of irony. However, what Gruber concentrates on, in his note to Shaw’s picture of Shaw by Shaw, is the artist and art critic who saw the potential in photography as that which makes up the ‘fame’ of its subject not merely documents the pre-existent fame of that subject. In constructing fame photography has become the appropriate artistic instrument and methodology of the art of its time. Thus for this picture Gruber cites, in his note, Shaw speaking in 1901:

If you cannot see at a glance that (…) the camera has hopelessly beaten the pencil and paint-brush as an instrument of artistic representation, them you will never make a true critic: you are only, like most critics, a picture-fancier … Some day the camera will do the work of Velasquez and Peter de Hooghe, [sic.] (…)[8]

I am assuming of course that Shaw saw fame as an appropriate expression of the appreciation of art. And that the same applies to Gruber. Of course, in its original etymology, ‘fame’ did not suggest the quality of the reputation of someone who is ‘talked about and reported’ but rather any tendency in someone that got them spoken about in public, whether that talk be positive or negative.[9] The characteristic ‘tendency’ I suggest is what I stated it to be above: ‘psychological penetration and expressive intensity’ of an art that values persons and personality. A photograph then does just document a real historical person for their own time but also communicates – or indeed creates in the manner of an original art ‘more universal meaning and emotion’, as I put it above.

Thus Gruber argues that he orders his photographic reproductions in order to explicate the source in the social meaning and emotion of the greatness of the photographic subjects and their distinctive domain or context rather than by chronology. This facilitates for him contrasting treatments of these contexts by photographic masters who might be distant from each other both in their geographical origin or decade in which they were working. I hope I have suggested how this happens in the comparison of images of Carlyle and Bernard Shaw as sage critics of the social and cultural world. Nevertheless, says Gruber, ‘each single portrait … is considered a masterpiece in its own right and without any need for other images to explain or to reflect its significance’.[10]

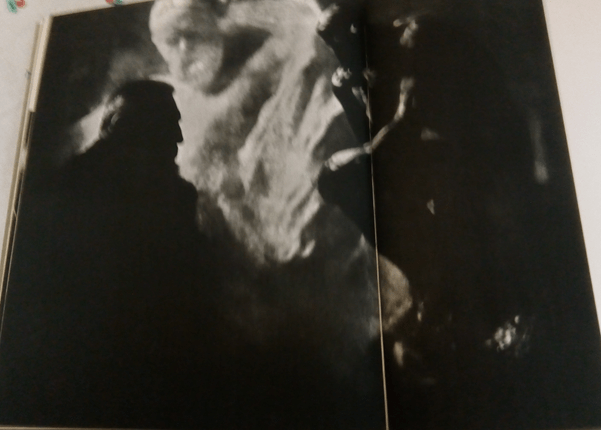

The most telling expression of this last point are the photographs given an entire fold of the book for themselves, especially, image 82, Edward Steichen’s photograph of the French sculptor, Auguste Rodin. Gruber’s note on the photograph shows how the photograph was staged and lit to create the sense that the man’s work reflected the greatness of his creative drive. Steichen chooses a trinity of figures in which the thinking poses and postures of the three reflect on each other through patterns of light and dark. Rodin’s Monument to Victor Hugo | Rodin Museum (musee-rodin.fr) at the rear bears the only visible face shown frontally in the trinity of figures but the ‘body’ of Hugo’s statue represented is unfocused, appearing almost numinous, spiritual or ghostly and, as if it were emerging from out of its darker background. It seems moreover to represent the full effect of the only light source in the piece. This light, apparently also reflected from the folds in the gestures of the body of The Thinker and at the statue’s rear, shows the form of that latter work alone through contrasting tones in the chiaroscuro. In order to represent Rodin himself, Steichen spoke of his intention to use a ‘silhouette’ to ‘give emphasis to that massive, expressive head’.

On a first look that silhouette seems imposed as a two dimensional form on the works we have already noticed. Yet, as our eyes scan the photograph. we notice that the head is three dimensional where light picks out the crown of the rear of the head, asserting that the source of the light that so complicates our take on The Thinker and Victor Hugo comes from behind that head. The reflected light here almost merges with some of the extended for of the Monument to Victor Hugo, just as the rhythm of the opposing heads in the composition as a whole connects the patterns of light representing Rodin’s head and that of ‘The Thinker’. For this is a truly composed piece of art, where the whole is more than the parts. It creates of the man, something that extends beyond the boundaries of his head and torso reflecting Steichen’s intention that ‘the most important thing to express’ in Rodin was the ‘man’s work and his genius’ as if they were the represent of his ‘Fame’.[11]

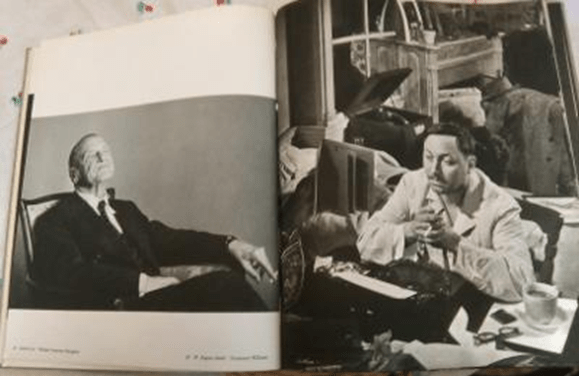

Some of the deliberately placed juxtapositions compare the idea of an artist’s specific role sometimes between geographical continents and others (as Shaw and Carlyle) periods of time. Let’s see how this done in relation to a comparison of two distinct persons who excelled in different continents as English speaking-and-writing playwrights, Somerset Maugham and Tennessee Williams.

Both photographs were made at a similar time (1952 and 1949 respectively) but the idea of the playwright is totally contrasting. Williams is shown as if at work, amidst the clutter and everydayness of his writing life and amidst its tool and objects, even those he might don, like the spectacles that lie by his coffee cup, itself a stimulant like the cigarette held quite purposively in an elegant holder but not in a way that boasts of any special privileged status. A typewriter awaits the thoughts that are being mulled. These thoughts though are, we know, as much about the muddle of everyday life as the surrounding room. what speaks out here is the meanings of an art located in the everyday and its own messy contingencies. Gruber says that: ‘Here, obviously, artistic disorder is an aid to ideas of genius and to the creation of sentences, acts and plays of exciting topical impact’.[12]

How different is Maugham. the writer himself, who thought it made him look ‘a snob’, which he insisted he was not. But there is a clear intention to separate Maugham from any everyday context that might speak of the nitty-gritty of work. Herbert List, Gruber insists, chose a ‘horizontally shaped’ or landscape design of the whole composition to distance his take on Maugham from that of other photographers who took portrait designs emphasising facial features alone.[13] Maugham’s languor perhaps tells us as much about the feel of his plays and stories as William’s different context tells of his. Everything about Maugham, even the full lighting on his face speaks of some pure production of thought and perhaps even spirit. And perhaps of a certain take on ‘class’.

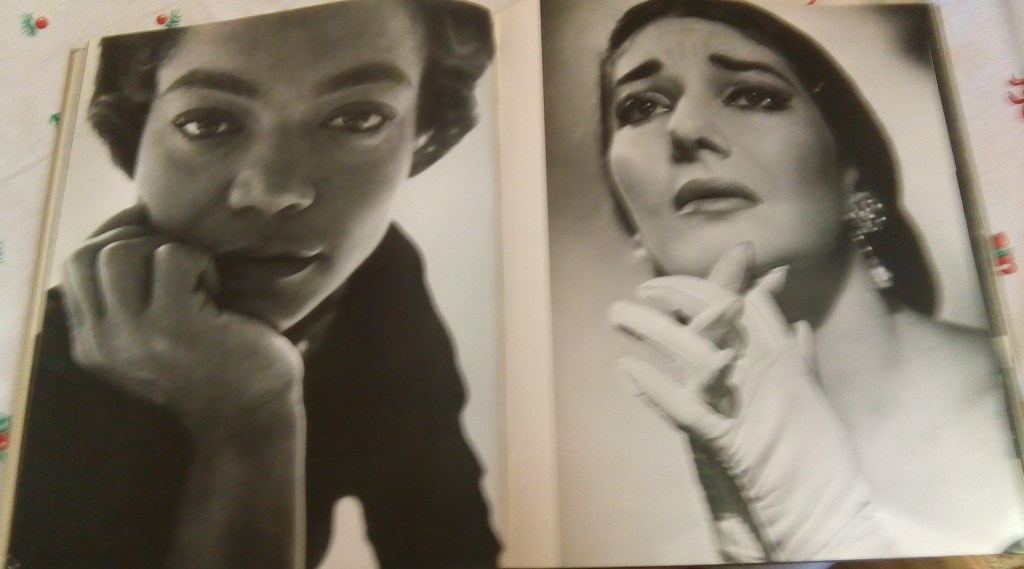

Contrasting kinds of artist are also shown in the case singers such as Eartha Kitt and Maria Callas, where genres of the art of singing as well as attitudes about class and unpleasant sexist myths of the sexual availability or otherwise of female bodies contrasted in class and racial terms speak out quite expressively, in ways I don’t intend to analyse.

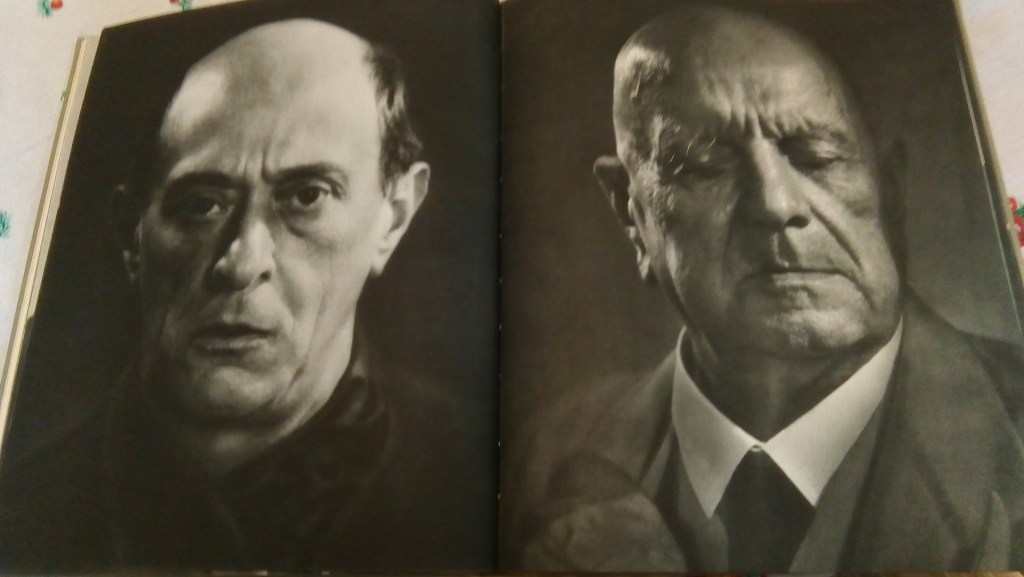

The following two contrasting male composers are not presented in ways that emphasise the whole body as is hinted at in the female singers, even where the whole body is not explicitly shown. Instead contrasts of occluded and inner qualities seem to be the aim of the contrasting kinds of fame of each man’s music.

Whilst Karsh in a book he called Portraits of Greatness emphasises Sibelius’ romanticism which is coded by external signs meant to indicate an inner quality of being.[14] This kind of fame thus demands that the man’s eyes are shut and his brow furrowed, and his mouth clenched. There are signs of intense interiority that speaks of feeling rather than thought primarily. The obverse is true of Man Ray’s brilliant portrait of Schönberg, where the eyes are wider than normative expectation emphasising a kind of hurt and isolating extremity of intellect and insight. Gruber sees this as a picture of the kind of source of ‘fame’ he say also in himself as an artist, as a person who inevitably breaks through the conventional norms accepted by others.

It is inevitable that he who by concentrated application has extended his limit of himself, should arouse the resentment of those who have accepted conventions which, since accepted by all, require no initiative of application.[15]

When contrasting visual artists, the contrasts can be seen in much more subtle features and especially the relation of the viewer’s gaze to that represented as that of the visual artist. In comparing Kokoschka, incredibly famous in 1960 but now no longer though still a favourite of mine, and Man Ray. Gruber’s commentary notes again contrast on one side an artist thought mainly as an expressionist romantic: wherein he quotes a reading of the photograph that perceives in it that in his paintings that is ‘restless’, ‘dynamically moving’, a ‘whirlwind’ and ‘the feverish atmosphere of capital cities’.[16] On the other Man Ray again gazes directly, rather than indirectly and with complex emotional potential as with Kokoschka, at the viewer and engages them intellectually. Kokoschka’s vulnerable and boyish look contrasts with the mature and grounded look of Ray. Ray’s use of innovative technique emphasises the material of his art – such as ‘the camera ground glass reticle’ that appears over the representation of his face.[17] Kokoschka, looking, as Gruber quotes, like ‘a frightened horse’ emphasises emotion and acts of empathy rather than intellectual recognition

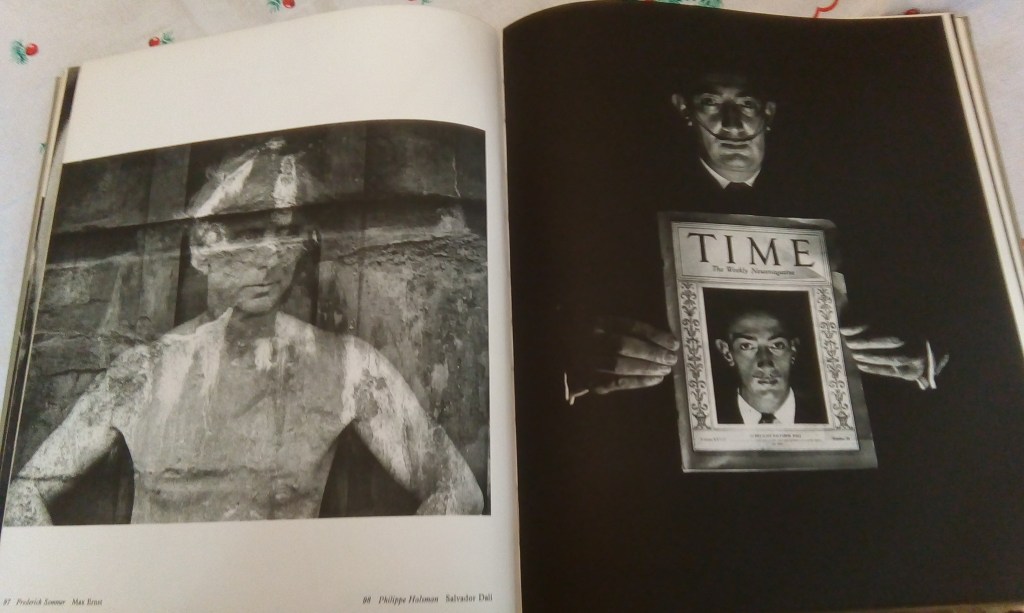

When the artists are from a particular school of art, such as the contrasting portraits of the surrealist artists Max Ernst and Salvador Dali, the purpose of the contrast is sometimes conceptual, showing how far a picture of an artist’s fame might include the central ideation which could be thought to characterise him individually.

Dali himself commented on Halsman’s portrait. The portrait utilises the word ‘Time’ which fortuitously separates two portraits of his own ‘famous’ face, and particularly his increasingly famous moustache, from two separate points of his career. Man Ray’s take on Dali of 1930 (published in the 1936 edition of Time shown here) is inset in Halsman’s 1954 portrait. Dali saw the 1954 picture as a whole as depicting changes over time in both himself and his artistic aspiration. The latter is symbolised in changes in the curation of his aging face. He was 29 in Ray’s portrait, but: ‘Since then the world has shrunk considerably, while my moustache, like the power of the imagination, continued to grow’.[18]

Whilst Dali’s playful commentary on the role of the artist and artifice in surreal art does capture a take on the nature of passing time that is recognisable in Dali’s other work, Sommers’ photograph of Max Ernst makes claims about how art might be redefined through accidents specific to its new media. This photograph was ‘declared “a work of art”’ by an august committee.[19] Sommer’s achievement is a kind of joke played on that committee of the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art. He utilises properties of photographic film, like the ability to superimpose images upon each other and create a kind of transparency in the presentation of figures in these images, and the features of familiar modern materials, like concrete to ape the values of high art. Gruber quotes Sommers playing games with the use of such visual illusions to ape the marble used in the sculpture of, for instance, the Ancient Parthenon of Athens: ‘Max Ernst, superimposed on concrete makes for the finest Pentelic marble’.[20] There is play on the placing of the eyes as an inset in the marble and in the obvious contrasts between the spare and thin torso of Ernst compared to the nude glories of idealised Athenian masculinity. It all tends to a surplus of meaning that is a kind of definition of an indefinable term such as surrealism.

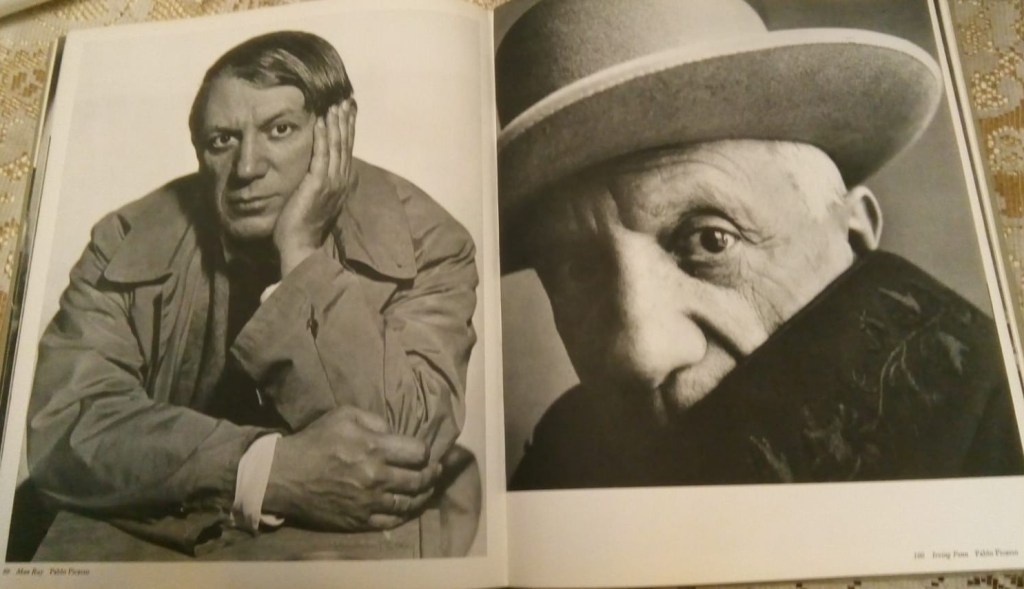

Of course, demonstrating the beauty and wonder of this book could continue throughout its many wonderful images and contrasts between contiguous images but I would like to end by looking briefly at an example where the work of two photographers of one subject, at different points in the career or stages of their self-fashioning as in the Dali case above, is examined. Since we are talking now about visual artists, let’s conclude with two contrasted images of Pablo Picasso.

Picasso in the 1930s and in the eyes of Man Ray is ill described by Gruber, in this instance, as ‘a passport photograph in the best sense’.[21] This portrait uses the play between surface and depth that is maximised by the enforced two dimensionality of photographic images. The face of Picasso has been receded into depth and relative lack of focus by the focus on Picasso right arm and a hand which protrudes into the picture surface. If it is almost stereotypical to concentrate on a visual artist’s ‘eye’, as in Penn’s wonderful later portrait, Ray understands that the artist’s eye is framed by the artist’s hands. The arms of the figure create a kind of rectangular frame for the eyes and are the active supports of the central figure. Picasso’s face is propped on one hand, whilst the other is both projected onto the picture surface also curves inwards pushing the whole torso, or so it seems, into the depth of the picture space. It is impossible to see this picture except through the torsion in the body where force sustains the image in the cusp between surface and depth, partly as an effect of the upward-facing but diagonal angle of the picture’s point of view.

There is so much less meaning in the fame of the Picasso portrayed by Irving Penn. Reduced, I would say – if brilliantly so – to a stereotype of the artist, now in his retrospective age: ‘… – the wide open, seeing eyes that have taught the eyes of his contemporaries to see things differently. … He is still on the world’s stage’.[22]

Trawling second-hand bookshops has been a life pastime for me. Occasionally you come across a superb little book like Gruber’s that opens up a treasury of thought and feeling about issues that are inescapable, such as the nature of fame and its relevance to those of us who have neither sought it nor wanted it. It’s unlikely you will want to find the same book, but try. You may find one that speaks to you, just as Browning did in nineteenth century Florence.

I picked this book from. Five compeers in flank

Stood left and right of it as tempting more,

A dog’s-eared Spicilegium, the fond tale

O’ the Frail One of the Flower, by young Dumas,

Vulgarised Horace for the use of schools,

The Life, Death, Miracles of Saint Somebody,

Saint Somebody Else, his Miracles, Death and Life,

With this, one glance at the lettered back of which,

And “Stall!” cried I: a lira made it mine.[23]

[1] Gruber (1960: 12) preface to Gruber (ed.) op.cit.(title)

[2] ibid: 11

[3] But despite this and her satire on Cameron in her play, Freshwater, Woolf decorated the right-side of the hall in her Gordon Square home with ‘a row of’ (male) ‘celebrities’ (including her father Leslie Stephen, Darwin, Tennyson and Browning). Woolf cited here and interpreted by Wendy Hitchmough (2020:42) The Bloomsbury Look New Haven & London, Yale University Press. For my reflections on this use this link.

[4] Woolf, V. (2017: 39) Freshwater: A Comedy by Virginia Woolf (The 1923 and 1935 Editions) Musaicum Books, OK Publishing. Quotation from 1935 version: Location 492.

[5] ibid: 40 (Location 505)

[6] Grubers Note to image 9 in Gruber (ed.) op.cit.: 131.

[7] ibid: 14

[8] cited ibid (note on image 11): 131.

[9] The term ‘infamy’ was a later invention (sources suggest the fourteenth century BCE) that disambiguated a word that had true qualitative ambivalence for the classical world by engaging with new contemporary meanings proper to the later Middle Ages, where fame from evil sources might need be divorced from those from good ones.

[10] Gruber, op. cit.: 12

[11] Steichen cited ibid: 146 (on image 82)

[12] ibid: 134f. (on image 25)

[13] ibid: 134 (on image 24)

[14] ibid: 137 (on image 35)

[15] Man Ray cited ibid: 137 (on image 34).

[16] Dr A. Schmoll (or Eisenworth) cited ibid: 147 (on image 87)

[17] ibid: 148 (on image 88)

[18] Dali cited ibid: 150 (on image 98)

[19] ibid: 149 (on image 97)

[20] ibid: 149 (on image 97)

[21] ibid: 150 (on image 99)

[22] ibid: 150 (on image 100)

[23] Browning The Ring and the Book Introduction Available at: https://internetpoem.com/robert-browning/the-ring-and-the-book-poem/