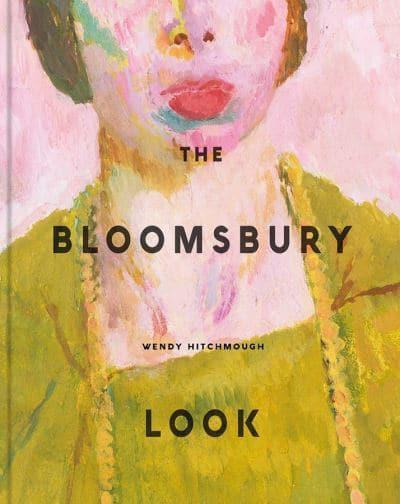

A personal but critical reflection on Wendy Hitchmough’s The Bloomsbury Look New Haven, CT & London, Yale University Press. Some thoughts, based also on having left an OU History of Art MA, about why the History of Art fails to justify itself as a distinct academic discipline?

I found this book on an independent bookshop’s shelves and bought it with great excitement (though all of £30) because it proposed to examine art and artists in which I had great interest and promised to do so through the prism of the concept of the ‘look’. A cursory examination seemed to promise to that the term ‘look’ would be understood through its usage in fashion, the art and theory of looking at art in different contexts, including contexts associated with crafts, design and everyday contexts of self-display. Its self-advertising suggested an approach through the notion of how artists and groups and artist might self-fashion their own identity, citing silently an approach to the history of written and graphic art devised by Stephen Greenblatt.

It is possible that it intended to do all those things I mention above but it never quite finds anything nuanced, or even coherent, to say about Bloomsbury’s ‘coherent, distinctive group identity’. It does not use it’s reflections on the objects it examines nor even to advance an approach that justifies giving the book the title it has, whether that object be a dress, an interior or a painting. Indeed it uses a kind of fluidity within its gaze upon such different objects (as they each demand our attention) rarely, except in one very promising instance (in critically examining Vanessa Bell’s (1915) painting Mrs St John Hutchinson, of which a detail appears on the book’s rather attractive cover (see above).

I would argue that one never quite gets Hitchmough’s point, in any coherent statement in her treatment of this wonderful painting. At one point she asserts how the figure and its clothing and decorative jewellery in the portrait is subordinated to a means of self-fashioning Bell’s own identity as ‘a polymath and a modernist artist’.[1] However at another, partly on the same page, uses the painting as if it merely intended to display the dress worn by Mrs Hutchinson as an example of how a possible real dress of Bell’s own creation and credits herself in doing so with some sort of unevidenced discovery:

The flattening of the composition and the reductive representation of Hutchinson’s features, with colours recurring in her skin tones and in the abstract painting in the background, challenged the conventions of British portraiture in 1915. Hutchinson’s dress, however, has escaped observation. The simple, asymmetrical lines of her top or dress, and her string of yellow beads, may have been identifiable among her contemporaries as an Omega garment and necklace.[2]

This is a prime example of having your cake and eating it that I do find typical of run of the mill history of art, at least that taught in The Open University, whose MA course I never finished. Are we talking here about the mimetic representation of a dress which might have been real and might have been fashioned by Bell for the Omega Workshops set up, in part to employ his Bloomsbury colleagues in the art of everyday life by Roger Fry? Or are we talking about a painting whose elements of represented objects matter merely because of the way their colours and design help inform the picture as a whole, as our main point of interest in it.

© Tate (also Hitchmough 2020: 91)

After all, it is not only that Hutchinson’s skin tones recur in the abstract painting behind her but that the boundary between the colour tones at one point get lost, such that the handling of the paint and relative form of the inner spaces of the surface of the painting is of more importance than the recognition of either figures or objects. Again Hitchmough can in her treatment say: ‘This is a painting about colour’.[3] Yet, she also says it is ‘possible this experimentation extended to Bell’s dress collection for Omega’.[4] This is yet another textual symptom of how this painting fails to be treated as the object that is a painting but primarily as a representation of the Omega dress collection as a set of objects that are dresses. And perhaps is not a dress in the picture but a ‘top’, since Hitchmough admits she cannot know if it is definitely an example of either. Of course we must also remember that Hitchmough has no real evidence that this is in fact an example of an Omega garment, whatever type of garment it be. So what are we told here about either art, history or the ‘self-fashioning of individual or group identity with regard to Vanessa Bell or the Bloomsbury Group particularly.

This painting is interesting precisely because of the games it plays with genres of painting it also references such as female portrait and abstract painting. Not only do skin tones recur and the boundaries of colour patches get lost in a kind of flattening abstraction based on the colour techniques of Matisse, but the depth illusions of portraiture get carried back into the abstraction so that the illusory feel and light and shadow of skin representations are borne into the abstract use of pink tonal patches and hatching in the domain that, in a representational view, is both Mrs Hutchinson’s body and face as well as the main space forming the abstract painting in front of which she putatively stands. And colour is constantly here creating liminal space along the boundaries of supposed represented objects.

Shades of brown and ochre echo rhythmically between a vertical strip on the abstract painting and immediately beneath it, the wood of the chair on which Hutchinson sits and the brown colour or shades thereof (we cannot, of course know since the this is the same question as asking whether the principles of this painting are mimetic or abstract) caused by light falling on the textures of Hutchinson’s top or dress or of the base colours of the material that composes the ‘dress’. There is no clear answer because the painting asks us to resist that very either/or binary in understandings of the role of painted surfaces as art.

This is not because, I would argue, that Hitchmough is an irresponsible art-historian but that the demand and insistence that the history of art is a single discipline (however varied its strands of reference to other disciplines) actually creates such irresponsibility as if it were a discipline. In my MA course, learners were not encouraged to follow up issues of theory and critical understanding of art but to summarise theories in a few words or two sentences at most, and otherwise say everything about the object taken as an essay’s focus. And if we understand ‘the look of contemporary fashion’ as transformed by Bloomsbury as Hitchmough’s topic, she covers it and never gets lost in what art history, in my experience of being taught it in the Open University, considers in treating art theory as if it were about advancing an argument rather than demonstrating your surface knowledge across he domains.

My disappointment is that the title, ‘The Bloomsbury Look’, took no cognisance of the theory of the ‘art’ or ‘looking’ or ‘seeing’, as devised a long time ago by John Berger. Of course Berger’s interest in the manipulation of perception or seeing is not exactly equivalent to an interest in the look, but the term has always been ambiguous between its reference to the act of looking or its results – the look created by a fashion for instance. It is also used thus in Berger. My expectation is that a work of scholarship needs to be tested by its ability to connect questions about the ontology of art, including theories of ‘looking at’, necessarily combine with the social history of looks (whether an individual’s self-display or social group self-display through concepts like fashion and propriety or a mix of both) and of the dynamics of seeing and psycho-active illusions of being seen. This is the kind of comment which raised such horror in my Open University MA course and led to me being asked to consider withdrawal. Yet my concern was ethical and about a concept of scholarship as truth. It was treated as a kind of showing off inappropriate to the discipline.

And at what cost? Let’s look at another reading in Hitchmough’s book, in which for me, much of what it means to take a queer perspective on art and the history of its production and reception. The treatment extends no further than a full page reproduction (of which it is truly worthy) and a brief reference on the following page in which the painting is contextualised as an example of Grant’s interest in male nudity as a function of his ‘intellectual modernism and progressive values at Cambridge’.[5] I quote the comment in full immediately below in order to test the probity of what I fully believe to be a typical moment in written history of art and its teaching (at least in my Open university experience).

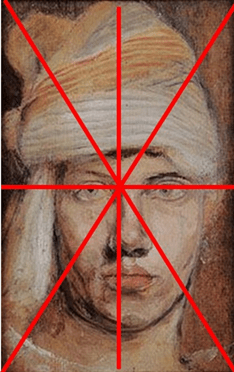

Grant explored his own individual identity, unclothed, in Self-Portrait in a Turban, … Again, the painting draws on a shared repository of cultural references: Bloomsbury’s identification with colonialism. Grant’s naked torso and arms are unidealized in this portrait and his expression is searching. In the painting’s first iteration …. [Hitchmough’s text here explores that ‘first iteration’ reproduced by her on p. 66, facing the ‘second, smaller portrait’] … A turban had been part of his recent disguise for the Dreadnought hoax. It also identified him with the colonial family backgrounds that he shared with the other members of the Group. In this self-portrait, however, and in a second, smaller Self-Portrait in a Turban, Grant’s interpretation of his colonial past is transgressive. The two paintings articulate a sexual availability. They appropriate the visual language of ‘oriental’ photographs of paintings of women and boys, eroticized as ‘other’. In doing so, Grant usurps racial and gender stereotypes to challenge the canon of Western, male self-portraiture.[6]

This is a decent enough commentary on the significance of the painting that contextualises it in Grant’s own biography, the iconographies of Bloomsbury identity and understanding of the images upon they ask us to look. It is a fair enough view that little more could be expected in elaboration, yet my dissatisfaction likes mainly at the failure to elaborate a problematic generalisation such as ‘articulate a sexual availability’ and to relate this to what it means to look at a figurative or auto-referencing painting. For me, it is inadequate not to look at how painting ‘articulates’ what it does because of the failure of this metaphor to make its meaning plain or the processes in the ontology of art it references. This would be so even if there is little or no evidence that the second, smaller’ portrait is, like the ‘first iteration a nude study and that nudes can be, as seems to be the unspoken (or unarticulated) assumption a means of attracting the eye to an available represented object – the naked body. For instance is the torso of the second portrait naked. That cannot be assumed and some marks on the painting seem to indicate the reverse.

To do any of the things that I think this section of the book currently fails to do, it would be required to say more about looks and looking, as I thought its title implied this book would. Indeed look again at this painting and it is a bout about the dual operations of the creation of one’s look in interaction with the act of simulated looking at the looker. The painting hinges on Grant’s represented eyes. In order to begin some sort of visual analysis, I would try, for instance, sectioning the painting between straight grid lines across its vertical, lateral exact mid line and its diagonal section lines. Thus:

Such a method has little to recommend it in theory but it does, at least, provide a pragmatic tool for more precise description and the avoidance of unsupportable statements like ‘articulate a sexual availability’. The first thing I notice is that both of the slightly asymmetrically placed pupils of the figure’s eye lie on the lateral mid-line. The face including the eyes and other features dominate the bottom half of the picture, just as the voluminous folds, wraps and cross-hatching that constitutes the painted turban dominates the top half. There seems room here therefore to elaborate our descriptions into some inclusion of the distribution of the painting’s representational and technical content. The face lies asymmetrically across the vertical mid-line, with the majority of the full facial features on the right of this line. My feeling is that this animates the face as if it were facing up to that upon which it, through the illusion of it having eyes, appear to look. And surely what it sees is the oncoming gaze of the viewer, whatever their gender identification.

The bottom half of the picture uses drawing techniques based on lines that adumbrate the face with some attempt at the representation of distance that lies beyond the surface of the picture. Those lines are associated with effects of real light on a resistant object and emphasise the definition and boundaries of the object. Its technical dependence upon the line, both straight and curved ones, in light and dark contrasts, is what gives this part of the painting a classical feel. If the face is classically Occidental (classical in the manner of painted versions of Ancient Greek sculpture) in its conventions of created beauty, it is drawn lines of distinct dark or light then, adumbrating the boundaries around which light falls on an object, that create that effect as an illusion. Sometimes the illusion is clear, as in the near straight dark line bi-sectioning the points at which the lips touch and close on each other. Dark and light more curvaceous lines aid the chiaroscuro effects of that almost perfect lower face, neck and chin. It feels as if it were formed on the edge of a Greek or Roman chisel and further contrasts the harder features of facial definition with the softer elements like the enlarged lips and eyes.

Without some such analysis and its elaboration to spell out the coding of visual language and contiguity to say the painting can ‘articulate a sexual availability’ is not only vague and unhelpful but plays into unwanted extensions of meaning. Hitchmough invokes codes that justify the dubious right of the viewer to take on the role of the perpetrator of sexual taking, literally the power of the rapist. This would have been more obvious had the figure or bust been that of a woman. It is the nature of rape that the rapist claims that the invitation to invade sexually is readable without seeking further prompts to establish sexual consent (articulated as this must be in language), merely from the body language of the person to be raped. The ‘look’ of the object of rape is attributed with the intention of giving a come-on to the viewer to act sexually, the usual excuse for rape in a which ambiguous signs can be adduced as unambiguous and inviting if they serve the power of the rapist. Yet these are the meanings that Hitchmough invokes here.

She does this in part by invoking, without articulating, arguments about Orientalism in Western Art. These ideas originate in the work of Edward W. Said but are intrinsically complex arguments, as even a Wikipedia summary will show. I would argue that their reduction to simple formulas is a characteristic of single discipline art-history and is what communicates when Hitchmough says Grant appropriates: ‘ the visual language of ‘oriental’ photographs of paintings of women and boys, eroticized as ‘other’’. This is, from the analysis I have already suggested as possible both a generalisation and under-argued. Grant paints himself, especially in the majority of the bottom half of our painting in clearly Western, nor oriental terms. The ‘turban’ is, of course, oriental and certainly interacts with the Roman characteristics of the painted bust of Grant.

The technique used to depict the turban also contrasts with the technique used to depict the face. Here the attempt is to show the fusion of colours in the folds and overlaps of the turban’s fabric. The representation is by clearly visible and irregular brush strokes that emphasise strokes of applied paint rather than more regular or near geometric lines. The use of dabs and patches of near impasto effects obliterate distinctions. The strokes and patches flow rather than create outlines. Now this sense of the diaphanous and liminal may well be a kind of orientalism but only a poor ability to ‘look’ at the picture would turn its iconology entirely into the available sexual ‘other’.

Rather the orientalism interacts with the Western bust. One of the important reasons that the face is vertically off-centred to the viewer’s right is because of the flow of the painting techniques associated with the oriental Turban into the viewer’s left of the picture. Here the impasto effects are compounded and soften the hardness of the classical face’s outlines. A near random brush stroke, composed also of impasto dabs to the bottom left of the picture appears to suggest material that clothes the neck. There is an indication on the bottom of the picture frame of something that might be fabric and might even be clothes which contrasts with the naked beauty of Grant’s classical face.

Now here I may be saying no more that Hitchmough intended by saying in our quotation, ‘Grant usurps racial and gender stereotypes to challenge the canon of Western, male self-portraiture.’ On what authority of analysis or reference, however, does this assumption rest. I find this kind of facility of assumption too much in single subject history art. Where is the attempt to articulate the assumptions about gender and sexuality in these large sweeping statements. I would argue that they do not exist and this is typical of the closed codes of social groups based on assumptions they never speak out to each other, so much are they assumed.

I think this matters because as a queer reader of books about culture I find the treatment of Grant’s sexuality here to rest on the kind of assumptions that don’t challenge the worst assumptions of either sexism or heterosexism, and this too was typical of the course I did, despite claiming to be feminist throughout. Too often the latter was interpreted as merely favouring women over men, without questioning either of those binaries. Were I to take my Grant analysis further (and I think I would need to were I writing a scholarly article) I would try and understand the way the painting paints sexuality into part-objects such as lips. I would want to do that to understand why the interaction of dabs representing eyes and lips is also important in Mrs St John Hutchinson by Vanessa Bell. Look again at the illustrations above to convince yourself that that requires doing if we are to move beyond simple views of the difference between mimesis, abstraction and the role of desire in constituting the ‘look’.

So overall, I remain disappointed that my outlay of £30, out of my pension, has not really facilitated positive learning but rather the reverse. Is it mean minded to except the vast outlays on academic units teaching and reproducing history of art to go beyond self-defence of a privileged group of scholars. May be. But at least I have now I have now got my frustration out in the open – blogged out is the phrase I want to use for these exorcisms of a mix of feelings and thoughts.

Steve

[1] Hitchmough (2020: 108)

[2] ibid: 107f.

[3] ibid: 110

[4] ibid.

[5] ibid: 68

[6] ibid: 68

4 thoughts on “A personal but critical reflection on Wendy Hitchmough’s ‘The Bloomsbury Look’ New Haven, CT & London, Yale University Press.”