‘…. have always been very unmanly in my strivings to get things all compact and in good train’.[1] ‘For all which idle ease I think I must be damned. I begin to have dreadful suspicions that this fruitless way of life is not looked upon by satisfaction by the open eyes above’.[2] Queering the need to work in works of art in Edward Fitzgerald’s Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam.

Reading Fitzgerald’s Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam again now I am retired has seemed a great pleasure. Perhaps because now I read it without any purposiveness or need, such as to write an essay as I did as a student or incorporate it into my teaching on Victorian literature as I did as an English lecturer. These domains of past work drive readings but now I read at relative leisure or, in a more severe self-assessment, comparative idleness. Nevertheless I then find myself wanting to write up a blog on it. Now my blogs aren’t seen by me as processed primarily as work nor as ‘works’ that have a product life outside the reflections they spur in myself. Maybe I should ask myself whether they constitute something quite idle, something that merely spends or consumes time rather than making something of it.

Having read the poem I found a Ph.D dissertation by Benjamin Hudson that more or less summed up my thoughts about reading it and other ‘translations’.[3] The other translations I mention include that of Robert Graves published in 1967, from a time in which I first became conscious of that poem.[4] Of course, whether Fitzgerald’s is a ‘translation’ is itself a bone of contention, especially with Robert Graves, who prefers Fitzgerald’s ‘jocular word, ‘transmogrification’’.[5] It was Graves waspish assessment of Fitzgerald that made me wish to write about what I admired in Fitzgerald on this reading and which Graves seemed to deliberately miss, focusing instead on Fitzgerald’s failure as a poet in being slavish, for instance to the original aaba rhyme scheme of the original quatrains or ruba’i, rather than inventive as a poet and committed to making sense. Look for instance at the tone of part of Grave’s ‘assessment’:

I sometimes think that never blows so red

The Rose as where some buried Caesar bled

Here (stanza24) the rhyme red dictates the inversion, and ‘I sometimes think’ does not match the original (our 19):

Each rose or tulip bed that you encounter

Is sure to mark a king’s last resting-place.

Nor, by the way, were Persians interested, as Fitzgerald pretends, in the sepulchres of Roman Caesars. …

Graves, R. & Ali-Shah, O. (1967) The Rubaiyyat of Omar Khayyam: A New Translation with critical commentaries London, Cassell & Company Ltd. p. 12

The tone of this tells us more about how we are guided towards a disrespect for Fitzgerald as a poet and scholar. He is mocked for his failure to see the incongruency between Persian culture and that of the Western European obsession with Ancient Rome. He is especially mocked for allowing rhyme to dictate and overwhelm any attempt to make sense to the point of using unnecessary ‘inversion’ and lazy subjectivity in an instance where the original, Graves insists, is merely using pithy argumentation. Hudson points out that the numerous instances of such a critique support Graves view of Fitzgerald, spoken out more openly in contemporary press articles as a ‘dilettante faggot’.[6]

Fitzgerald does get the last laugh here. The original manuscript provided to Graves by Ali-Shah turned out in the event to be an obvious forgery that any serious scholar might have noticed. Moreover, this forgery was dependent entirely on Fitzgerald’s reordering of the quatrains.[7] As I reread Graves in the light of Hudson’s argument for instance, I noticed that fact about the ordering might have been hinted at to a scholar by Graves comparison of Fitzgerald’s claimed stanza 24 and ‘our 19’. Only in the second edition of the Rubaiyat (1868) does Fitzgerald’s quatrain quoted here by Graves appear as stanza 24. In the first (1859) first edition, it was stanza 18.[8] In all others (including different versions of the 1872 third edition) including the composited 5th edition from which the Ali-Shah forgery was ultimately derived, it was stanza 19 as in Graves’ ‘translation’.

Hudson’s main concern with Graves’ charge that Fitzgerald was a ‘dilettante faggot’ is that it makes the link between dilettantism and an abusive use of the labelling of queered sexualities in the twentieth century critical rejection of much of Victorian poetry. Hudson’s portrayal of the literary dilettante as itself a device in the queering of accepted norms is powerful and convincing. It leads to fine and hard to contest readings of Fitzgerald’s major work. However, Hudson may not, I feel, take the conceptual implications of what he sees as a cognate defence of dilettantism and of queer sexualities far enough into the standard cognitive building blocks and thought processes in the ideology of Victorian England: the revaluation of the concept of ‘working for a living’ and the increasing moral weight given to such endeavour (in every Victorian novel for instance other perhaps than Thackeray- Fitzgerald’s greatest literary friend) over living off unearned income from any source.

Of course, such a move must take another step towards dilettantism in literary criticism than does the ironic posture of it in Hudson. It must return to biographically based criticism. For Fitzgerald, who was not past comparing his family to characters from his friend Thackeray’s Vanity Fair, is a prime example of the gentleman living of an income he himself never earned. The dilettante is an extension of this exemplum – a man who plays at work without necessity (a bit like a retired man on a pension writing blogs, I have to say quite self-consciously). But such a role is constantly referred to by Fitzgerald in his correspondence as a version of idleness rather than work. Even the writing of his voluminous letters is seen as evidence of indolence and passivity of mind, body and spirit – as, in the heteronormative terms of the new Victorian bourgeoisie as ‘feminine’ rather than masculine. This is particularly the case when Fitzgerald writes to attractive young men who were his contemporaries Like John Allen and William Makepeace Thackeray or later his chosen young favourites for whom he would spend time and effort to please and indulge such as William Kenworthy Browne, Cowell (his gateway to Persian culture and therefore a more complex case) and later the sailor, Posh Fletcher. Martin tells us John Allen, a clergyman’s son, hated the ‘sin’ of indolence but shows also that Fitzgerald would often write to him, almost coyly, brandishing this very ‘fault’, in the most feminised of terms:

You, who do not love writing, cannot think that any one else does: but I am sorry to say that I have a very young-lady-like partiality to writing to those I love: but I find it hard work to those I care not for.[9]

I am an idle fellow, of a very ladylike turn of sentiment: and my friendships are more like loves, I think.[10]

Fitzgerald wrote a poem that must amuse modern queer readers more even than it amused its writer and recipient, but which cannot be used as evidence for this point since the latter readers would be less likely to seek innuendo in it:

But a day came that turned all my sorrow to glee

When first I saw Willy, and Willy saw me!

Nevertheless, even with Thackeray, Fitzgerald, in the very throes of asking Thackeray whether he should marry (a woman) stresses his own lack of masculine force in working towards a goal: ‘I have always been very unmanly in my strivings to get things all compact and in good train’.[11]

We can see all this as very playful, as indeed it is, but we should also remember how charged the language of masculinity and labour was for Victorians in the very furnace in which a meritocratic democracy is being imagined. Fitzgerald’s ‘idleness’ was based on unearned income, yet his close friend (at least in the early days of Fitzgerald’s admiration for the poems of 1830 and 1842), Alfred Tennyson imagines an ‘idle king’ in Ulysses who will nevertheless uses the term, ‘strive’ (those things in which Fitzgerald is ‘unmanly’ in his letter to Thackeray) as the very as the very kernel of what it means to be a ‘man’ and a hero:

We are not now that strength which in old days

Moved earth and heaven, that which we are, we are;

One equal temper of heroic hearts,

Made weak by time and fate, but strong in will

To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield.

This poem cannot be understood without the work of Thomas Carlyle, which was admired by both Fitzgerald and Tennyson, not least On Heroes, Hero Worship and the Heroic in History (1840) and Past and Present (1842). Thought of primarily as a philosopher, Thomas Carlyle, at the time, Carlyle yoked the concept and performance of masculinity to the concept of work (striving, seeking and not yielding), an idea he was readily to attribute to Goethe. Fitzgerald admired Carlyle even as he aged into discontented raving, which still remained, in Fitzgerald’s estimation, ‘that of a Genius: and of a sincere Man too – that indeed is his Madness – and I am touched, I say, by his passionate Cries’.[12] Carlyle’s most famous quotation on the cognate meaning of work and masculinity can be found in Past and Present, and, though early, is still a ‘passionate Cry’ in the name of manly strivings and ‘natural’ potency.

A man perfects himself by working. Foul jungles are cleared away, fair seed-fields rise instead, and stately cities; and with the man himself first ceases to be a jungle, and foul unwholesome desert thereby. The man is now a man.[13]

Yet despite the admiration for Carlyle as man, Fitzgerald was still able to both demonstrate that he was at ease without paid labour or professional status, with manly strivings indeed in any sphere. His lesser works, even those of translation, could happily spout the Victorian eulogy of manly endeavour. Take Salámán and Absál, for instance, which openly subscribes itself to the Sufi wisdom of an original that Carlyle would have recognised. It’s a translation from Jámi Noureddin Abdurraman and Fitzgerald urged it on publishers as a fit companion piece for the publication of the Rubaiyat. In that former poem Salámán represents a perfectly masculine principle of intelligence, ‘not of Woman born’, whose aim is to work for the benefit of the world. He must literally burn from out of him by ‘Ascetic Discipline’ the idle and indulgent worldly feminine principle represented by the wet nurse who becomes his lover, Absál.[14] This poem is of the same material as Carlyle’s use of the example of ‘Mahomet’ as an exemplum hero. Manhood, work and intellect are conjoint disciplines. Even in his private letters, Fitzgerald was capable of seeing his hours languishing in idle sport, though only fishing or hunting is the sport in question, with a beautiful youth such as Browne was as something that should look sinful and to be repented, burnt out of him:

…. we shall go to a Village two miles off and fish, and have tea in a pot-house, and so walk home. For all which idle ease I think I must be damned. I begin to have dreadful suspicions that this fruitless way of life is not looked upon by satisfaction by the open eyes above. One really ought to dip for a little misery: perhaps however all this ease is only intended to turn sour by and bye, and so to poison one by the very nature of the self-indulgence. Perhaps again as idleness is so very great a trial of virtue, the idle man who keeps himself tolerably chaste, etc, may deserve the highest reward; the more idle the more deserving.[15]

The question here of course is tone. There is no doubt that Allen, the letter’s recipient, did believe that self-indulgence and idleness was sinful but is not Fitzgerald not lovingly subjecting Allen’s belief to some considerable witty irony. The language of ‘dip for a little misery’, though no doubt related at some deep level to Fitzgerald’s bouts of depression as recorded by Martin, is a self-consciously ironic reference to the alternative to idleness, as is the exaggeration of the infernal costs of worldly pleasure. My own feeling is that Fitzgerald is as much defending idleness and epicurean enjoyment, even a little lack of chastity (in mind at least) as he is invoking Victorian certitudes about the primacy of ‘many strivings’ towards perfectibility. In that sense this is a Sufi playful allegory in the service of something far more open to worldly pleasure and that is not allegorical at all. Similarly Sufi allegorical readings of Omar Khayyam quatrains suggest that wine is merely the symbol of intoxication of the mind with the divine of God. Cowell, Fitzgerald’s scholarly young friend, believed this and pressed it on Fitzgerald, to little success, as does Graves and Ali-Shah in their ‘new translation’ that turned out to be an Ali-Shah forgery.

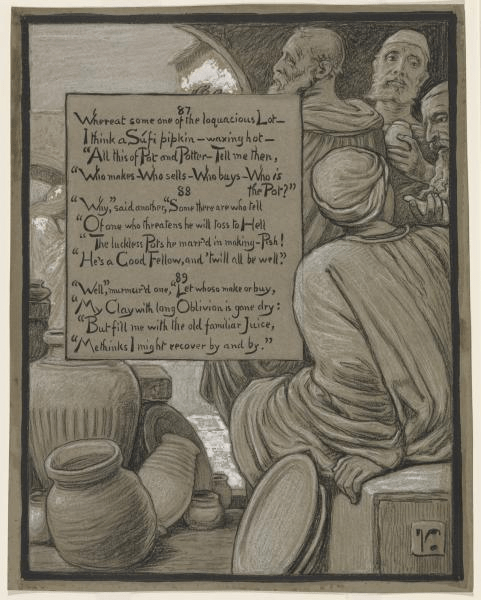

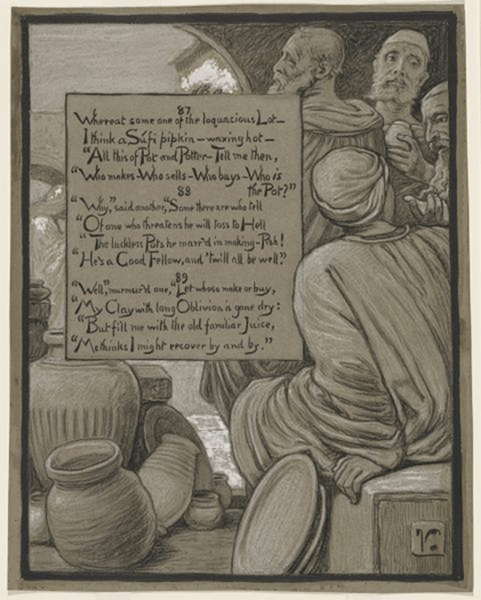

After all the ‘manly strivings’ of critics, we may be left with a ‘work of art’ that takes the position that work is of lesser importance to the enjoyment of life as it passes that some see as an example of Fitzgerald’s open espousal of Epicureanism. But that is to forger that a work of remains a ‘work’ and whose process is work, whatever its end use. Of course, it might, as a ‘Book of Verse’ read ‘beneath the Bough’ might promote idleness and sensual indulgence.[16] But that is the least of its paradoxes. Such a paradox can be safely left to the ‘Loquacious Wine Vessels’ themselves to ponder since they are its exemplum, as in the illustration with which I start. My interest is in the queer undermining of manliness in the proponent and object of such a work of art. Richardson, in a lovely book, commandeers the poem’s ‘ungendered vision of love’ as something that ‘now’ reads as like:

a large-tent gathering, an inclusive celebration of love with no group or groups stigmatized, marginalised or excluded.[17]

In a further extension of such claims, not entirely absent from Richardson either, Juan Cole sees the original verses as representing, in part at least, a ‘secular, Muslim counterculture in the medieval Middle East’, in which the ‘LGBT poet was a central () figure …., and often as powerful in his or her own domain as clerics were in theirs’.[18] I really don’t see that strong versions of these arguments need carry the day. In a weaker and more partial form however, it identifies an element in the poem that propels some of its most radical wish fulfilments. The poem contains for me a wish-fulfilment of this kind, sustained as dreams are in Freud, by a whole unseen machinery of dream-work.

Dreams engineer fulfilments that cannot be simply seen as such – they must also be warnings and recognitions of that which militates against fulfilment. They are compromise formations in Freud’s terms. And this is why it is such a great poem and why Richardson is right to focus on quatrain LXXIII of the1859 edition:

Ah Love! could thou and I with Fate conspire

To grasp this sorry Scheme of things entire,

Would not we shatter it to bits – and then

Re-mould it nearer to the Heart’s Desire.

This is a wish held back by the improbability and uncertainty of mood in ‘could’ and ‘would’, such that desire for what we want in thought and feeling and are prepared to work towards (so often called little more than a day-dream) meets its limits, in ‘reality’ or in world politics or in the human condition and the fact of death, whilst in the process of straining against them. Wishes, given free rein, would destroy the existent and inadequate world in order to rebuild a basis for their revolution that ignored those limits and boundaries. Wishes may appear to be the opposite of work and yet, it is work – the process that produces art – that makes them expressible and in doing so somewhat realises them. A wish is of course a state of the mind but once expressed, even if in compromised form that admits of limits to its achievement, it makes possible the cognition of an alternative to a world that has become our norm and seems because of that alone unchangeable.

In practice though, how does this mean that we read this poem. I intend to look at two quatrains, starting with that one of Fitzgerald’s objected to in its first two lines by Graves above and for which he substituted his own version. I give a number of versions below.

| Fitzgerald 1868, XXIV I sometimes think that never blows so red The Rose as where some buried Caesar bled; That every Hyacinth the Garden wears Dropt in its Lap from some once lovely Head. |

| Graves & Ali-Shah 1967, 19 Each rose or tulip bed that you encounter Is sure to mark a king’s last resting-place. While scented violets, rising from the black soil, Record the burial of some lovely girl. |

| Avery, P & Heath-Stubbs, J. 2004 The Ruba’iyat of Omar Khayyam London, Penguin, 165 Every plain where tulips bloomed Was reddened by a prince’s blood; Every knot of violets springing from the earth Was a beauty-patch on a darling’s cheek |

| Cole 2020, 42 Each rose is tinted by the gore shed on The field by antique fallen emperors, And every violet takes its colour from A beauty mark on a slain sweetheart’s cheek |

What Graves appears to dislike about Fitzgerald is the personalisation of the thought process of the poem. Where the other translations (I can’t speak for the original Persian) adduce evidence of some glory lost and authorise the generality of that loss, Fitzgerald introduces a moment of random reflection (of sometimes – but not always – thinking) that focuses not on authoritative argument about mutability and death but on changes that could be because of variations of personal mood rather than just a reflection of a universal truth. This is not a feature of any other translation I quote above.

Fitzgerald’s language is also more imprecise culturally than others. Here, as elsewhere he introduces a garden for which there is no support in this part of the poem (other translations insist on a more generalised piece of earth than a garden). Not only is there unlikely reference to Caesar, given the Persian distaste for Roman authority adduced by Graves to critique Fitzgerald, but there is also the near anachronistic possible introduction of a Hyacinth, which must recall the story of Apollo’s male lover, transformed into a flower after receiving an accidental but mortal wound from him. That Graves felt this typical of a ‘dilettante faggot’ might be adduced from the fact that he ensures the dead lover referred to in the last two lines in his translation is a girl. Only Graves introduces normative gender expectations to the poem, which remain in each other version gender neutral as they so often are in Persian poetry, according to each of the authorities used in this work. Fitzgerald’s emphasis on the military ‘field’ is present in Cole’s version and supports a non-heteronormative reading of the identity of the ‘darling’, who has been ‘slain’, presumably on the field of battle and whose beauty has been rendered into a flower.

There is nothing that can be called definitively gay in any of these versions but there is definitely a queering of expectations in all of them except Graves who has gone to some lengths to normalise heterosexual assumptions. Cole, for instance, argues that the ‘lack of gender in Persian pronouns makes’ reference to a lover’s gender necessarily, ‘ambiguous’. [19] This is a point also reinforced when Richardson cites the modern scholar Hamid Dabashi saying of the poem that: ‘the uncertain gender of the beloved emerges as the destabilising force … in which masculinity and femininity are decidedly undecided’.[20] The anachronism and shifting focus of Fitzgerald’s translation begin to seem in this light one of the major achievements of his work, where our sense of final meaning never rests and we are torn between visualising fragmenting bodies and landscapes. They are part of the queerness of the poem, where, for instance, we find ourselves in difficulty to find the relation of body parts in the personifications implied in the metaphors ‘head’ and ‘lap’. Whatever, this is, its is sensual rather than sensuous and not appealing to logic but something whose reality is insecure as in a dream.

And that indeterminate wish fulfilment suffuses even the comedy of the Loquacious Vessels, even if we look only at the three quatrains above which I reproduce again here.

There is pointed satire against Sufism in making the ‘Sufi pipkin’ long to work into allegory its own situation: throwing questions directed at itself directed at the Intellect, like the very decided allegory behind Salámán and Absál, rather than to the matter that is all a Pot is. Only the last Pot is vindicated in asserting that it how it feels in its own matter – the Pot accepts wholly its own wet and drunken senselessness that comes of being used by the living rather than being dried up with the forgotten dead for whom no matter is of any use. Even recovery is of no concern because it is merely part of the process of being unaware of any end other than being full of juice.

The experience of this poem is often of great immediacy where the feel of immediate gratification is the only way in which a wish can be fulfilled. The great symbol of this immediacy is the lip but I suspect it may apply to other parts that are also body parts in the poem, like the tongue or finger. Lips move in speech but they also touch other lips and perhaps even drink at them, including the lips of both vessels and lovers. Lips mediate safely or unsafely between categories like land and water on rivers. They are the beginning of a child’s language and of its silent final breath in death. How often lips are all these things at once in this poem, so that all we are left with is the sensual feel of lip on lip as it enchants sound alone or with another lip, be that the lip of the same person or another. Look finally at the lips in these instances which are literally unanalysable except in terms of our sense awareness of lips touching each other everywhere – above and under the ground – and being touched. The texts are all from the 1868 version.

XXV

And this delightful Herb whose tender greenFledges the River’s Lip on which we lean –

Ah, lean upon it lightly! for who knows

From what once lovely Lip it springs unseen.

…

XXXVIII

Then to the Lip of this poor earthen Urn

I lean’d, the secret Well of Life to learn:

And Lip to Lip it murmured – “While you live

“Drink! – for once dead, you never shall return.”

XXXIX

I think the Vessel, that with fugitive

Articulation answer’d, once did live,

And drink; and Ah! that impassive lip I kiss’d,

How many Kisses might it take – and give.

…

XLV

And if the Cup you drink, the Lip you press,

End in what All begins and ends in – Yes;

Imagine then you are what heretofore

You were – hereafter you shall not be less.

Nothing is certain here – certainly not passivity in love-making because passive (impassive is changed to ‘passive’ alone’ in texts after 1868) lips can begin to live as once live ones have died. I love that term, ‘articulation’, in which many possible meanings begin to live. If a dead cup lip touches a living lip, is it because it is itself the dust of dead lips, and can its touch of many lips over time join together and articulate with others. You will not make clear sense of this, nor should the poem allow you. What you must do is to be able to feel the touch of lip or of lip upon lip as a sensual possibility whether the lip is that of a living or dead thing.

This is a finely worked poem but its work is that of an idle sense, where words constantly fail to take on their role as something distinct from the matter they name, however varied in type that matter be. To some critics it will seem lazy and unprofessional, lacking the sign that the poet is doing his work, (as Fitzgerald sounds to Graves). To others it queers the relation of sound to sense and means there is no rule or law which will draw us out of the experience it offers. It is a wonderful poem, even though I am deeply aware oy my own inability to articulate its greatness. In part this is me. In part it is that the poem does not respond to people if they only want to work on making it work on their own terms.

Steve

[1] Fitzgerald cited Martin, R.B. (2013 ebook of 1985 first hardback publication) With Friends Possessed: A Life of Edward Fitzgerald London, Faber & Faber (Location 1468)

[2] Fitzgerald cited Martin, R.B. (2013 ebook of 1985 first hardback publication) With Friends Possessed: A Life of Edward Fitzgerald London, Faber & Faber (Location 1789)

[3] Hudson, B. (2016) Exquisite Amateurs: Queer Dilettantism and Victorian Aesthetics A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Georgia in Partial Fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy. Athens, Georgia. Available at: https://getd.libs.uga.edu/pdfs/hudson_benjamin_t_201608_phd.pdf

[4] Graves, R. & Ali-Shah, O. (1967) The Rubaiyyat of Omar Khayyam: A New Translation with critical commentaries London, Cassell & Company Ltd.

[5] ibid: 1

[6] Graves in The Daily Telegraph March 25th 1968 cited Hudson, op.cit. p.35

[7] Hudson, ibid. pp.35f.

[8] See Appendix 1 ‘Comparative Texts’ p. 142 of Dekker, C. (1997) Edward Fitzgerald Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyám: A Critical Edition Charlottesville & London, University of Virginia Press.

[9] Cited Martin, op.cit, Location 778

[10] ibid: Location 820

[11] ibid: Location 1468

[12] Cited ibid: Location 4373

[13] Carlyle, T. (1844: 137) Past and Present, New York, William H Colyer.

[14] Quotations from the Epilogue of Salámán and Absál. Available in The Fitzgerald Centenary Edition free on Kindle.

[15] Cited Martin, op.cit. : Location 1789

[16] As in quatrain xi in the 1859 Rubaiyat.

[17] Richardson, R.D. (2016: 159) Nearer the Heart’s Desire: A Dual Biography of Omar Khayaam and Edward Fitzgerald New York & London, Bloomsbury USA.

[18] Cole, J. (2020:144-7) in the ‘Epilogue’ of The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyam: A New Translation from the Persian London & New York, I.B.Tauris Bloomsbury Publishing PLC, pp.71-148.

[19] Cole op.cit: 124.

[20] Cited Richardson, op. cit: 159

One thought on “‘…. have always been very unmanly in my strivings to get things all compact and in good train’. ‘For all which idle ease I think I must be damned. I begin to have dreadful suspicions that this fruitless way of life is not looked upon by satisfaction by the open eyes above’. Queering the need to work in works of art in Edward Fitzgerald’s ‘Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam’.”