Visualizing the Male Erotic: Art, Pornography and Psychiatric Labelling

There is for me an iconic scene in Steve McQueen’s Shame where the hero Brandon, played so often wordlessly but brilliantly and intensely by Michael Fassbender, and ever on the look for his next high on sexual experience, cruises the corridors of a gay club’s sex rooms. He finds a man who ‘goes down on him’ and we watch the drama of his face as the unseen sexual act occurs below the scene which cuts off under his torso, and what alone is literally seen in the film’s display. I think this scene brilliantly placed in the film’s narrative, endlessly reflective of scenes of the homogeneity of sexual goal amid the diverse means of its process and achievement. I fixate on this scene, perhaps itself one of the many acts of scopophilia invited in the film.

Scopophilia is a psychiatric and psychoanalytic term that has long been colonised by theorists of film because it is a means of discussing the achievement of bodily pleasure from the act of looking, or the gaze, alone without the necessity of direct appeal to other bodily senses. it makes sense that great and prescient film-makers will exploit its domain of associations between body and visual experience. I think we need to think a little more deeply about how visual pleasure and bodily pleasure are associated in a thinking filmmaker. I think it goes a little deeper than is suggested by Decca Aitkenhead in her commentary on her interview with Steve McQueen, after the 2014 release of his blockbuster film, which has a more tangential relation to visual pleasure in that it involves some amount of pain, 12 Years A Slave.

Instead, his films just show what people do – in unflinching detail. So we saw exactly what excrement smeared over prison cell walls and crawling with maggots looks like, or a sex addict masturbating in a toilet cubicle, and now we see exactly what a slave looks like hanging from a noose, while other slaves avert their gaze. But we never see inside their minds. For McQueen, the visual artist, showing what they look like is what matters.

When I ask what new ideas or emotions he thinks the film offers, he admits, “I don’t know. I was just interested in telling the truth by visualising it. Visualisation of this narrative hasn’t been done like this before, and I think that’s the thing. I mean, some images have never been seen before. I needed to see them. It’s very important. I think that’s why cinema’s so powerful.’[1]

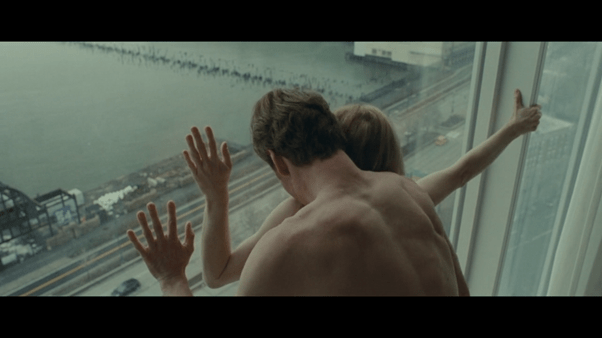

Aitkenhead here interprets McQueen’s interest in the visual as an interest in observable truth but I see a much more nuanced set of meanings in McQueen’s Statement about the power of cinema: ‘some images have never been seen before. I needed to see them’. What Aitkenhead loses from this sentence is that McQueen’s interest is in not just in seeing but the ‘needing to see’, a need that spreads into the unseen such that no image is simply what ‘I see’ but what parts of what I see are seen, and which remain unseen. This is as true of the masturbation scene in Shame referred to here by Aitkenhead, as of the sight of death and torture under the cruellest of circumstances. And that is why I started with the scene in the gay male sex rooms. We don’t see the bodily act of fellatio that occurs to Brandon but merely his responses, although other acts of male-on-male fellatio are visible in glimpses as the camera follows Brandon through this usually unseen interior. What we see has to be assessed in terms of what we don’t see. Hence the interest in males who have sex with women a tergo where the woman is pressed against a window, theoretically visible from outside. Brandon sees such an act and then reproduces it with a prostitute against the high window of a hotel. This is an important scene and I will return to it later in this piece.

But this concern with the play of desire over the previously visually unseen, and its consequent partial fulfilment only therefore in acts of visualisation over a time period, speaks to what is deepest in McQueen’s work. The use of a motif of the revelation of seen from unseen is derived, in Shame at least, from theories of sexualised scopophilia or, voyeurism.

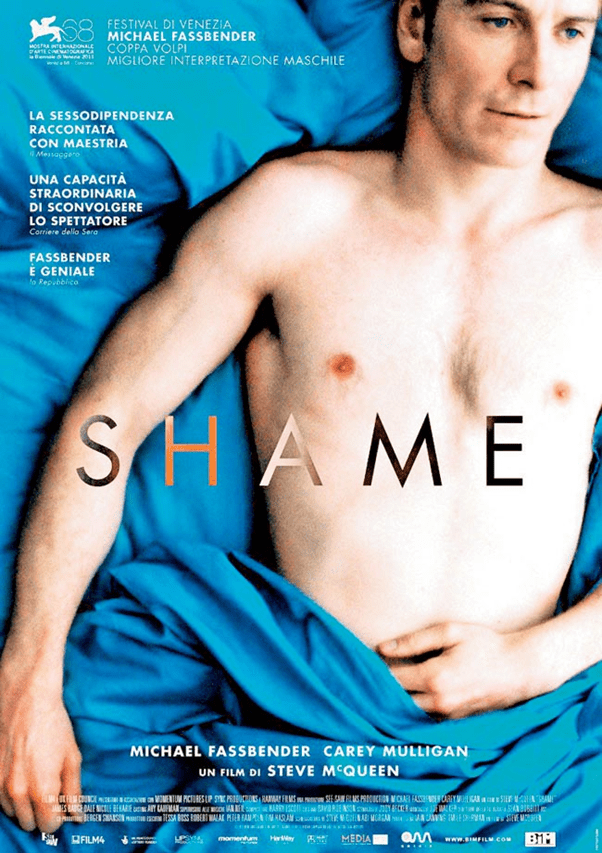

All viewers of film are implicated in such acts of voyeurism. Think, for instance of the early scenes in which Brandon visually emerges from the shadow of his room at the opening of the film and how the camera interacts with the space it defines (and the space predefined with the flat’s interior architecture). This includes the use of partially open doors, to only gradually reveal, and then wholly Fassbender’s generous version of the phallus the film trains its viewers to want to see emerge from the unseen. Even the poster advertising the film makes the wish to see what is unseen in direct terms of the hero’s phallus, and we have to remember that by this point of his career, Fassbender is noted for this physical quality, part of its means to attract viewers to see the whole film.

The poster (for the Venice Festival showing) uses a shot from the film where Fassbender is prone on the blue sheets of his bed – sheets in which his sister Sissy will sleep with his work boss significantly and over which both he and she giggle – with his torso exposed. The actor’s hand is a focal point in the lower frame and is caught in the action of pushing down, against or under the sheet in the direction of the actor’s phallus. The motivation to scopophilia and the desire for the ‘unseen’ but imagined could not be clearer.

Aitkenhead might have got to this point to by looking at what is occluded as well as what is visually seen in the masturbation scene in the company toilets in Shame to which she refers. The same is true where the viewpoint of Sissy of her brother’s sexual self-stimulation is denied to the point of view of the film-viewer who sees his actions from behind Brandon’s back, when she inadvertently enters his bathroom to register such a sight. What we see is always set against the penumbra of what we need to see, where need covers a legion of potential associated sensations, emotions, thoughts, and narrative meanings. The frisson of Sissy seeing her own brother’s sexual nature, locked in a rather submerged incest theme is implicit in that scene.

More plainly it is also in another masturbation scene in which Brandon seeks pleasure in the shower cubicle of his bathroom and the camera plays across the obstacles to transparency in the seen and seeable, both in the steaming of the transparent shower surround and the droplets of distorting water running down it.

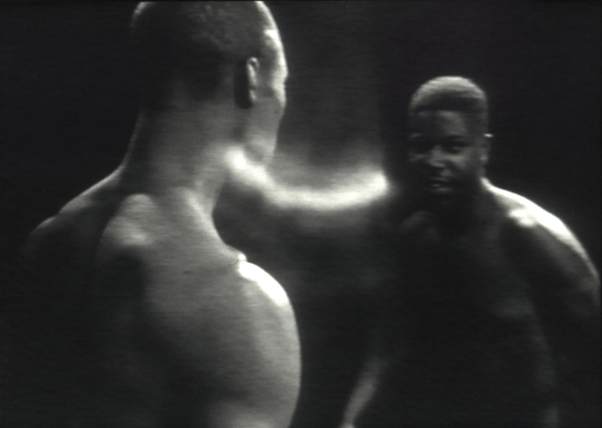

We will see windows on subway trains too in the film as screens for graffiti art that obscure an object of desire seen in the subway station from within the train. But the strain emerged incredibly early in McQueen’s work, in his first 10-minute video Bear (now in the collection of the Tate). I first saw this film in a wondrous exhibition named Flesh at the newly re-opened York City Art Gallery in 2017. Aitkenhead too refers to this film but does not explore its intrinsic links to McQueen’s intrinsic motivations in the exploration of intersectional interactions between race, queer and masculine identities and visual tropes. She says:

Like many artists, McQueen experiences the world [of the serious ‘art’ film] from a highly singular perspective. As a working-class boy growing up in 1980s suburbia, “there were no examples of artists who were like me. When did you ever see a black man doing what I wanted to do?” His father kept telling him to get a trade; even when his son began to be successful, “he was still taking the piss, saying to my friend, ‘Do you understand what Steve does?'” McQueen’s first film, Bear, was 10 minutes long, silent, and consisted of two naked men, one of them him, wordlessly circling each other, staring and sparring.[2]

The question in McQueen’s speech is an important one in relation to visualisation: ‘When did you ever see a black man doing what I wanted to do?’ The very fact of being working class or black or queer male (or combinations of these) means that aspiration to socially privileged and entitled roles such as actor, director has no visual models to follow or to use as means of explicating, to one’s father who thinks one better off in an established trade such that the latter can understand what his son, Steve, actually is doing in the world. His father can see, that is, nothing in what his son does. Bear is very much a film about looking – the two proponents, one of whom is McQueen himself, stare at each other, whilst the camera longingly explores the relation of two bodies in uncertain opposition and / or concert. It is a film about needing to see meaning in the visual and is the model for the later work and the theme I have already suggested. And it is a film about scopophilia, particularly in relation to black skin and straining flesh.

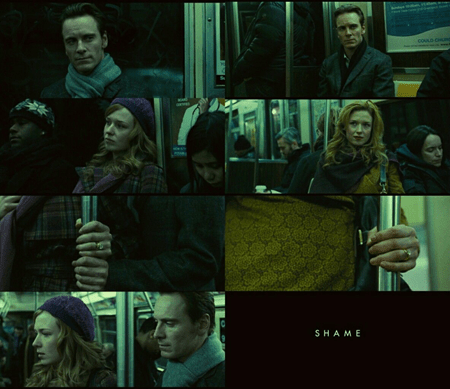

In Shame the voyeuristic sexualisation of vision has many forms. At base is the transformation of women to that subjected to the male gaze, in which male eyes see under women’s clothes the object of their sexual desire (or gaze in Laura Mulvey’s term). The obvious examples in which Brandon eyes a woman across the aisle of the subway train and undresses and rapes her symbolically. There is one at the beginning of the film where the woman is a victim and flees the gaze quite literally, one at the end where woman and man exchange an active sexual gaze with each other. But it is not only the actors who gaze at each other but the camera itself which focuses on parts of the body or the fall of a dress in which sexual invitation can be intuited and/or invented, especially by the male, irrespective of the female’s wish to participate or no. This is the purpose of the of the opening and closing scenes it would seem as in the medley of pictures (captured by Wai Yan on Pinterest) below

Brandon eyes the opening between a woman’s legs as a sexual invitation in those scenes. His behaviour mimes male metamorphoses of the shape of a woman’s body or any sort of cleavage she shows or orifice suggested as inviting. The camera captures these seen moments where the woman herself is not participating in seeing, or promoting themselves to be seen, except in the interpreting male gaze. Here is a stereotyped instance.

Other instances of sexual voyeurism are more complexly and gendered queerly rather than heteronormatively, as I tried to suggest in my opening. If you haven’t seen the film, an exquisite trailer shows enough of these instances, including some I have already cited. It includes lots of scenes where the male gaze is focused and its genesis in formal and apparently formal group male behaviour suggested. They include scenes of men in groups, exerting hold and power over the visual world they dominate. It is these images and the the images they create for their own consumption in the realm of soft pornography that tell here. But my own feeling is that is a phenomenon at the surface of the film, although a cognitively powerful one. McQueen himself suggests that he sought a setting a setting in which the male gaze and its characteristic quantitatively large hunger forefronts. When asked in 2011 why he set the piece in New York, he said:

I wanted to place the character in the setting of excess and access. And New York seemed to be the ideal place for this character. We’re not there yet in London as far as 24-hour service is concerned.[3]

In a sense this seems to suggest that McQueen’s interest lies not in themes I have chose to focus but in the visual demonstration of ‘excess and access’, in the means by which men control the production of images of sex and the female body in pornography and other aspects of patriarchal consumer capitalism. For me this displays that part of the film that critics were soon to jump upon, that the film studied a medicalised condition of social and individual excess, which soon became labelled ‘sex addiction’. It makes the film appear the study of a medicalised state, including its social as well as personality based aetiologies.

In some readings, such as that of Emma Brockes in The Guardian, the study of male sex addiction is a kind of psychiatric case study that is mirrored by Carey Mulligan’s similarly motivated portrayal of his female double. Richard Le Beau makes a case for seeing Mulligan’s character traits as symptoms of borderline personality disorder (BPD). However Le Beau also goes on to say that nothing in the film creates an interest in Mulligans’s character or psychopathology (no medical condition is named in the film for either character) that is at all equivalent to the cameras visual and narrative interest in the body and body language of Fassbender. Brockes review focuses so teasingly on the cusp between the image of the attractive male that unites Fassbender, his past roles and the character Brandon, that it itself becomes almost symptomatic of the culture’s over-fascination with maleness and the attraction of male control of the visual, even at the level of the attractiveness of his vulnerability: ‘I’ve heard he is, or at least was, a big party boy, but his aspect this morning is pure butter-wouldn’t-melt’.[4]

The fascination with vulnerable men that Brockes illustrates, as a reflection of the culture I believe rather than the authorial persona, is a combination of admiration of size, sexual reductivism (from man to boy) and suspicion that the visual appearance of masculinity, whatever its meaning, is an artifice. In that sense, it reflects again McQueen’s ‘shame’ that the appearance of men and their interacted behaviour is hard to understand from its mere visualisation and we are left, as McQueen’s Dad about him, about what exactly men do. There is a sense in which men are a constant puzzle and their apparent command of the gaze an artifice that shatters under conditions under which they are looked at and wherein much remains ‘unseen’.

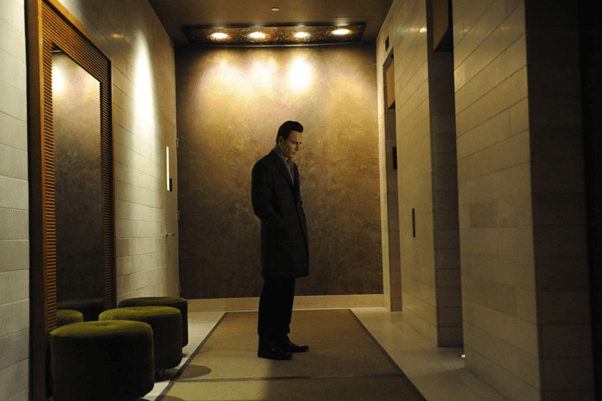

The gaze of the camera in Shame is constantly that of the narcissist, looking in intoxication at an image that becomes vulnerable under any variation of the gaze into critique or less than admiration. Only flat surfaces reflect the prepared image back to itself. Any depth creates shadows and uncertainties, wherein the imaged masculinity fails to satisfy and recedes, or drowns (the fate of Narcissus being behind all of this) in its background). Here are two images to illustrate this. In both the head lowered in shame is also the head of Narcissus looking for a kinder reflection. And the film continually reminds us that, in New York at least, a 24-hour ‘service’ industry is there to redeem men’s self-image that can be bought by those with the monetary power and capital to do so.

In this picture, Brandon has turned his back on the flat surface of a mirror and begins to fade under the scrutiny of downlighting or to be about to be absorbed by huge holes in the environment that represent the lift doors. Dark encroaches throughout. In another moment of narcissistic shame, Brandon sits head down in front of a huge flat plane of glass into which his whole attitude appears to make him want to fall to certain death. The moment follows his sexual failure with a young woman who looks for something genuine in him. He will redeem himself in the next scene by having sex with a prostitute a tergo as she is pressed against this flat plane, such that he sees in the flat surface of the window not a depth in which he might fall but into the self-image he has bought with money to ‘service’ his ego.

I do not think then that we will get far into this film by seeing it as case study of mental illness. Rather it is about the tropes sustained in patriarchal and heteronormative culture. Characters in the film, especially men, continually distance themselves from Brandon, His boss has the best and most resonant line of the film when he exposes Brandon whilst allowing him the excuse that his asocial desires might remain unseen if blamed on an intern. This boss is as much the narcissist as Brandon, though less successful. Men in business pride themselves in the film by the line: ‘You’re the Man’ (tis section is on the trailer). Yet his ‘hard drive’ (I think the pun is clear) whilst he can say to Brandon (also on our trailer above): ‘Your hard drive is filthy … I mean it’s really dirty’. The narcissist discovered is a scratched surface, a smeared mirror or window. Strangely this aspect of McQueen art, I find best articulated by Fassbender, and reported in Aitkenhead’s review:

The addiction is, in a way, just a metaphor – “Scratch the surface of what’s socially normal. I suppose in some way all of us have something we display to the public and things we feel too ashamed of or uncomfortable with to reveal to other people” – but one that required a lot of courage in the performers. Mulligan was, he says, “brave and willing to throw herself into it. There’s no safety net, and that makes it exciting and scary; …

What was McQueen’s advice?

“He’d say, ‘Surprise me’.”[5]

I do not know if Aitkenhead fully explicates Fassbender’s wisdom regarding McQueen here. The life of a visual artist is one in which the display rules of a society, the rules we are socialised into about what it is acceptable to make visible in public and what is ‘filthy’, interact with equally powerful rules about what artists and art are allowed to display and own of the mass of material that can form their subjects. Only what we are surprised to see will make it clear that display rules are being twisted and manipulated and made to appear as they are in public, as hypocritical, I would say, as a ‘decent’ man like Brandon’s boss who business and socio-cultural ‘married’ self will not be sullied by Sissy, Brandon’s sister, making demands on him. I agree this is not about ‘sex addiction’ but that such a ‘condition’ is a symptom of a diseased social order, just as I cannot accept that Carey Mulligan’s brilliant portrayal is that of a woman with BPD. She too reflects her making and unmaking by a world that rejects her every need.

Steve

[1] Aitkenhead, D. (2014) ‘Interview: Steve McQueen: My Hidden Shame’ in The Guardian 4 Jan. 2014. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/film/2014/jan/04/steve-mcqueen-my-painful-childhood-shame

[2] ibid.

[3] McQueen (2011) cited Another ‘Michael Fassbender and Steve McQueen on Shame’ in Another Magazine Sept. 15th, 2011. Available at: https://origin.anothermag.com/art-photography/1377/michael-fassbender-steve-mcqueen-on-shame

[4] Brockes, E. (2012) ‘What’s a nice boy like Michael Fassbender doing in a film like Shame?’ in The Guardian 6 Jan. 2012 available at: https://www.theguardian.com/film/2012/jan/06/michael-fassbender-shame-mcqueen

[5] Aitkenhead, op. cit.

One thought on “Visualizing the Male Erotic: Art, Pornography and Psychiatric Labeling”