‘Rougetel scratches his ankle in sleep. As vulnerable and exposed as the corner of a book’ (my emphasis).[1] Reflecting on Nicholas Shakespeare’s (2020) The Sandpit London, Harvill Secker.

Andrew Taylor, a considerable writer of well-known detective thrillers, disputes the high praise of William Boyd cited on this books back cover, saying: ‘When it comes down to it, a thriller, even a literary one, really ought to thrill. This one doesn’t’.[2] The damning phrase seems to be the term, ‘literary’. At one level it disdains the attempt to mix the genre with effects that though praiseworthy, and Taylor does praise with some understanding of some of the novel’s literary qualities – as ‘well written’ and with a rich vocabulary of words of which Taylor pretends no earlier acquaintance. Although the ones he quotes – such as ‘maculate’ and ‘indelible’ do not seem overtly literary to me – one gets the point since ‘maculate’ at least rings with association of the notion of the immaculate in religio-sexual myth.

‘Indelible’ on the other hand was used by me and every other working-class schoolboy in my school (in association with the fun to be had with trademarked ‘indelible ink’). Where Taylor cuts at the ‘literary thriller’ deepest, is its refusal to tell the story in a thrilling or convincing way. It’s use of ‘flashbacks’ is said to be ‘leisurely’ (just what one would expect of an Oxford toff like Shakespeare), its tendency ‘existential’ (I think this term refers to its hero’s psychological characteristics) and its ending faulty in the most conventional of ways. Of the latter, he says:

His problems are finally resolved by the appearance of a deus ex machina that manages the difficult feat of being simultaneously predictable, implausible and unsatisfying.[3]

Now, we could say that this characterisation is a matter of taste. Laura Wilson in The Guardian, for instance, speaks of the novel as thrilling in precisely the way denied by Taylor whilst also admiring its literariness. It display, she says, in a review specifically addressed to its quality as a thriller, ‘an insidious escalation of menace, and paranoia that fairly shimmers off the pages’.[4] But I think both reviewers have a point, not least Taylor in identifying a plot element that sits uneasily in the book and, although I find this element deeply satisfying, it demands attention and readerly and literary-critical surprise.

This element is a story concerning the narrator’s old school friend, Rougetel. It’s a story that clearly indicates that this is no ordinary element in a spy thriller. Moreover, in my view the chapters concerned draw the reader’s attention to their deep oddness. Reading them feels as if a modern novel had been invaded by something quite foreign to it. I see this element as comparable and perhaps influenced by the character of The Scholar Gypsy from Matthew Arnold’s now too little-known poem.

The purpose of Arnold’s Scholar-Gypsy was to represent an ideal from which the everyday world was distant. That it is as near as we can get at the other-worldly, a pure love of disinterested learning, of ‘sweetness and light’ as he characterises the purpose of a university, and Oxford University in particular, in Culture and Anarchy. The Scholar retires from the life of purposive self-interest and avoids the mortality involved in the perpetual strife through which self-interest realises its goals:

Till having used our nerves with bliss and teen,

And tired upon a thousand schemes our wit,

To the just-pausing Genius we remit

Our worn-out life, and are—what we have been.

Thou hast not lived, why should’st thou perish, so?

Thou hadst one aim, one business, one desire;[5]

Rougetel, like the Scholar Gypsy himself, has specialised in a life of disinterested learning which alone constitutes his SOLE aim, business and desire. How different is he from the fathers, sons and mothers guided by international finance, politics and gain in the interests of self, class and / or group that constitutes the ‘powerful and pervasive freemasonry which extended into the deepest crannies of international finance’.[6] The school represented by the present day Phoenix is a place wherein children were ‘laundered’ from the stain of emerging from ‘great fortunes without apparent cause’.[7]

It had once offered an education that encapsulated, or so he tells The Iranian physicist, Marvar, ‘some decent values’, those of an old ‘professional middle class’.[8] But Rougetel is more than the bearer of decent values or even of those past average boys like Dyer himself. The singleness of his aims as a self-educator (which I see as so analogous to those The Scholar Gypsy’s mythical personification of learning) comes from having no parental, class or professionally defined aim in promoting his learning. His parents die while he is young.

He learns an altruism so universal, even in small instances, that links his story to the central symbol of the novel, the sandpit. When both are boys he reveals the hiding place of Dyer’s lost World War II plane toy in the school sandpit, the story of which being told to Marvar inspires the latter to pass on his formula for solar nuclear fusion (and thus a means to cheap alternative energy, which will disrupt international exchanges based on material fuels) by burying it too in the same sandpit, but so many years later, for the older Dyer to find.

As one reads this of course the judgement that these plot elements are, ‘simultaneously predictable, implausible and unsatisfying,’ in Taylor’s words becomes a choice for the reader to take. Rougetel is not so much explained by his backstory as constituted by it into many layered allegory like a character from Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queene. One’s tolerance to such plot elements of literary fiction is tested especially in the late chapters of the novel where Rougetel again is forced, unknown to himself, to be an element in the novel’s main plot. How are to find here a narrative that is plausible to make this link. it must happen at the level of literary perceptions and private meanings. The meaning of Rougetel emerges out of reflection on relation between the two characters by Dyer himself, in which he sees elements of himself as well as huge differences. Rougetel’s:

… steady, self-contained gaze intimidated Dyer who, being one himself, recognised the solipsism of an only child. Rougetel had had none of the counterbalance of a sibling to old up a corrective mirror, or a son like Leandro. he had lived, emotionally and intellectually, on his own resources, without the encumbrance of family or belongings, so that to all intents he might have come from Pluto. He had no partner, dependants, domicile, job, yet something mysterious had taken their place, a spiritual life stripped of egoism, full of revelations that he sensed but had yet to articulate, …

Rougetel, it penetrated Dyer, as they entered Phoenix Lane, was not looking to be rescued or understood; he was too involved in trying to understand. He was content his life, it arrangement suited him. Not for an empire would he be in Dyer’s trainers.

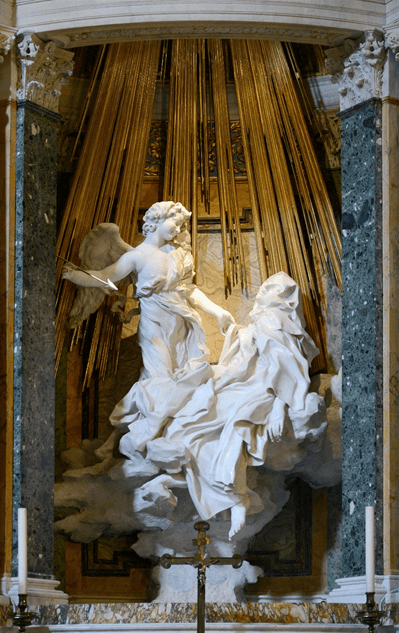

There is so much here that strikes me as unusual in the prose but not because it is ‘literary’. The central insight into Rougetel ‘penetrated’ Dyer, yet that verb seems so absurdly baroque. For me the violence in the word ‘penetration’ it recalls Bernini’s Ecstasy of Saint Theresa. Thoughts about people aren’t usually said to penetrate one as desires and convictions and beliefs just might. And it works for me as a sentence precisely because there is something about religious vision in the passage (in the language of ‘spiritual life’ unarticulated ‘revelations’) that prompts the potential of a kind of metamorphosis of Rougetel as if he indeed he came from somewhere unearthly, of which ‘Pluto’ is an oversimple guess. Yet this feeling is mixed with the language of everyday recognition too; A sort of fusion that comes from a dead metaphor like ‘walk in Dyer’s shoes’, usually an idiom for developing empathy with another person, being consciously revived by the choice of a highly contemporary word for modern male clothing: ‘walk in Dyer’s trainers’.

Many readers who like to ‘evaluate’ novels will have already chosen Taylor’s view that ‘thrillers’ shouldn’t be playing these games, especially at their near denouement. Thrillers which evoke such symbolic / allegoric journeys at this point can’t be that thrilling, they will insist. But I believe that what Shakespeare does here is to defuse the expected sensations of a reader (the thrill bomb implicit in wanting to race ever faster to knowing how to resolve matters in the novel’s content) into a more serious and less sensationally founded endeavour.

Shakespeare risks losing the dynamic of the thrills heretofore built into a narrative mainly involved in resolving a plot based on international espionage because he wants something else entirely to cross the reader’s mind, which is to muse on what education, learning and especially reading, ought to mean to modern readers.

And I would assert that this is precisely Matthew Arnold’s purpose (for a different age) in The Scholar Gypsy. In fact the novel explains why our take on Rougetel’s life, in comparison to that of Dyer, who had already appeared in an earlier Shakespeare novel of accidental international espionage The Dancer Upstairs, is so minimal: ‘To cram forty years into a conversation over lunch is not easy. Dyer’s sense of Rougetel’s life was riddled with gaps. What did he do for money, sex?’[9] It is precisely important we know as little of Rougetel’s life as possible so as not to deflect from his role as a symbolic reader. Rougetel’s mission is described hyperbolically. His vision of life is an ‘inner sun’ was also, ‘the entrance to his path.’ In comparison to this need to learn, all religions of all nations are seen as, ‘imperfect constructions of the human intellect for what transcended it’. It is a search for the ‘best of what has been thought or said’ (my italics), which Arnold saw as the true ideal project of Oxford University:

(Rougetel) believed that he had glimpsed the best of himself, of what he could be. From this moment on, he wanted to be that person as often as it was possible. a receptive void disengaged from the intricacies of living.[10]

An allegory indeed for learning, disinterest and perfect human striving for its own transcendence. More importantly an idea of the ‘receptive void’ in which learning might take root. Rougetel is forever associated with book and the ‘incessant reading’ of them.[11] There was for him no such thing as a ‘bad book’.[12] His reading supplements the book, just as his Post-It notes do.[13] This novel, we soon discover, if we open ourself to it, is full of libraries, books and readers (good and bad) even an ‘Oxfam bookshop’, smelling of ‘body odour and urine’,[14] – just as it is with writing that can or cannot be read, usually because we do not possess the code to do so. In contrast to Rougetel’s absorption and commentary is Dyer’s own hunt amongst book ‘spines for a volume to distract him’.[15]

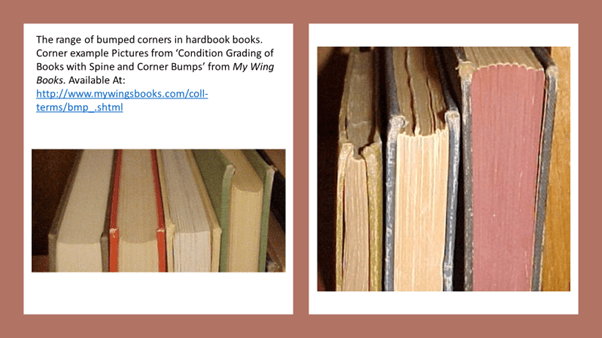

It makes sense then that the reading of Marvar’s formula for nuclear fusion in the sun, goes to Rougetel, whom have we seen has an ‘inner sun’. Those three men (Marvar, Dyer and Rougetel) are bound together in the novel by acts of trust that each may become the ‘receptive void’ able to uncover from the sandpit of Marvar’s research, its buried value. Marvar’s post-it note is combined with Dyer’s account of its transmission and dropped into the receptive void of Rougetel’s bag. And at the heart of this moment in which Rougetel is compared to a book: ‘Rougetel scratches his ankle in sleep. As vulnerable and exposed as the corner of a book’ (my emphasis).[16]

But how does the simile work. It works not to show the grandeur of Rougetel as a fictional reader but to show the vulnerability of the world of books itself. As a book-collector myself, I wonder how non book-collectors read it. Second hand books are condition graded by common signs of wear, tear and general aging in use. The most vulnerable spots include the corners – ‘bumped corners’ in the trade being a sign of condition that determines the value of that book. You can see this in the Figure below and the trade-related website it comes from.

But why should we see Rougetel and books as vulnerable? I think it is because they both represent an idea of how knowledge is contained, accessed and processed that is in danger culturally, a world in which knowledge and physical objects are not differentiated. The Old Bookbinders is the name of a pub.[1] Some books are NOT read. This is an inevitable lesson in this novel. Dyer first hides Marvar’s note in a book by Professor Madrugada (the Spanish for ‘early morning’), of which he is to date the sole reader in the history of The Taylor library.[18] Hence, he knows few people have an interest in reading it. That only changes when what exactly Dyer is reading becomes of interest (for the simple reason that unread books are good hiding places for documentation) becomes of self-interest to spies from various nations who thinks he possesses an industrially and politically sensitive subject.

I find this novel so sad. It is state of the world novel from the point of view of a high ideal of literacy I remember from my childhood but is no longer a sustainable belief. It starts as a thriller. It then sacrifices the thrills expected of that genre in order to become a novel of the vulnerability of the world of book-reading rather than digital material, which books can also become. Leandro Dyer, his son, has a future that will not offer books primarily as a means of entering the world (one kind of ‘portal to the world beyond’) that The Idylls of the King, Treasure Island and Greenmantle offered Dyer himself.[3] Needless to say these books can only characterise Dyer’s boyhood past not the present on offer to Leandro which is the digital world of shallow intrigues and non-communal ‘Smuggertown’ interests.[4]

It is my firm belief that careful reading of this novel would raise many other issues about books and readers, including self-consciousness about the use of favoured writers like Graham Greene, Basil Bunting and others. Echoes of other books will be found in its language and narrative elements. This isn’t just a literary game. If it were, why would Shakespeare hide them under cover of an espionage thriller. There is much to discover here – if anyone takes the trouble. Reading some reviews suggests that this will not be a certainty. Books are vulnerable: there may be little hope for them or of achieving a good reading in this world.

Steve

[2] Taylor, A. (2020) ‘Oxford Skulduggery: The Sandpit By Nicholas Shakespeare reviewed’ in The Spectator 25th July 2020 Available at: https://www.spectator.co.uk/article/oxford-skulduggery-the-sandpit-by-nicholas-shakespeare-reviewed

[3] ibid.

[4]Wilson, L. (2020) ‘The best recent crime and thrillers – review roundup’ in The Guardian 17th July 2020. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2020/jul/17/the-best-recent-and-thrillers-review-roundup

[5] Matthew Arnold The Scholar Gypsy. Available at: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/43606/the-scholar-gipsy

[6] Shakespeare, op. cit: 34

[7] ibid: 35. The debate about the authenticity of the quotation, owing as it does a debt to a rather poor English translation of a sentence from Balzac’s Le Père Goriot, is interesting. See: https://www.ft.com/content/40399358-77ca-11e3-807e-00144feabdc0

[8] ibid:33-5

[9] Ibid: 381

[10] This and quotations that are only about Rougetel in ibid: 377

[11] ibid: 381

[12] ibid: 390

[13] ibid: 382

[14] ibid: 153

[15] ibid: 195

[16] Shakespeare (2020): 413

[17] ibid; 246

[18] ibid: 219.

[19] The quotation and the books all referred to ibid: 25

[20] ibid: 94, Sumggertown ibid: 69