‘There is a great deal of losing and forgetting about Ravenna as well as physical dismantling, which is also a form of forgetting.’[1] Reflecting on the ways and means of history as a form of remembering the lost body of the past’s being. Judith Herrin’s (2020) ‘Ravenna: Capital of Empire, Crucible of Europe’ London, Allen Lane, Penguin, Random House.

Judith Herrin is a renowned historian and authority on a long period of history that has not in large inspired the kind of creative interest that it intrinsically deserves. The sources of the History of the late Roman Eastern Empire and the links between it and Western Europe are lost both by the destruction of its records or by their burial under deliberate lies and fictions. Whilst destruction can be caused by war and political and/or religious division, those same power games also defeat enemies by misrepresentation. Those records which (mis)represent, or get (mis)represented, include too a culture’s symbolic art and architecture.

History-writing rarely tells the story of major world-shaping historical change in ways that preserve truth. The multiple contemporary perspectives of past cultures, especially ones that failed to survive the victors of historical struggles for hegemony get subjected to extreme and meaning-changing metamorphosis. And though it is common to blame Edward Gibbon’s book The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire for these misrepresentations in relation to the Byzantine Empire, such ritual blaming of one historian and his monumental book is largely to miss the point. History always is about both accidental and deliberate dis(re)membering of something that was quite different while it lived. Subsequent collation of the fragments and bloody members of the dead or dying past is intrinsically problematic, as Dr. Frankenstein would be the first to tell us. Hence Herrin, in the title quotation locates the problem in acts of ‘losing and forgetting’ that characterise the experience of lived history itself and not just those records we call written history, where misinterpretation by contemporary present standards rather than those of the contemporary past is one example of loss and practical oblivion-making.

Much more so when the topic is the city of Ravenna – a contested part of the Western remnant of the Roman Empire. Its functions as a trading centre were lost to the silting of the Po estuary to the new city of Venice. Likewise its connections to Constantinople were subjected to the aspiring ambitions of different Western powers to covet not only power but symbols of how that power claims, or could be made to appear, validity and legitimacy. Hence this history of Ravenna ends with Charlemagne becoming ‘Holy Roman Emperor’ in The West, using spolia from that city’s basilicas and ideas from the authority underlying its symbolic imagery to make that fiction stick. The most potent lie about this historical transformation was the infamous Donation of Constantine. Herrin’s prose description shows how making a new written history of the fourth century AD through the creation of fallacious sources for current action (current at least in the eighth century) based on a blend of real and invented sources of evidence from the past shaped memory as a means of validating the interests of powerful groups in the West. It is insufficient to label such creations ideology, they shape both practice and the nature of Occidental institutions and their thing-like symbols.

Constructing the Donation to fit fourth-century circumstances, papal officials carefully used genuine imperial laws, Pope Sylvester’s known decrees and particularly his Life as recorded in the Roman Book of the Pontiffs to justify papal rule over the western part of the empire. They also codified the superior authority of the church over lay rulers.[2]

Of course, such constructions were open for re-interpretation, often on the basis of equally fallacious evidence. Lay rulers were able to play this game using the trappings of the Eastern Empire’s creation to justify themselves – even Henry VIII, and more so his daughter Elizabeth I, in sixteenth-century England used the notion of legitimated Empire to justify his rights of primacy over a universal church authority claimed by the Popes. But such games were ne-er so well played than by Charlemagne, with whom Herrin ends her story of Ravenna. And that for a reason. Carolingian legitimacy was based on claims embodied in the institutions of Ravenna, the ‘crucible’ of Western claims of a nascent autonomy justified by the Emperors of the Roman Empire under the Gothic Kings who ‘managed’ Ravenna under the nominal will of the Constantinopolitan Emperor, especially Theodoric the Great in the 5th-6th, centuries. Both managed kingdoms that were at liberal variance from Constantinople bot administratively, ecclesiastically (being Arian in religion – and thus Homoian in the beliefs in the relative but similar nature of Christ and God the Father – rather than believers in the ruling of the Council of Nicaea (325 A.D.) that God, The Holy Spirit and Christ were co-equal entities of one God (the Trinity).

Charlemagne in especial sought to harness the power of the imagery that bridged possible contradictions between his claims to be an Emperor over all things earthly and spiritual on Earth (and dressed in the coin above as Roman Emperor par excellence), in the name of The Holy, whilst the champion of the one true religion. He was thus adopted for his Imperial Palace a whole set of cosmological and iconographic elements of the architecture, art and motifs of Theodoric’s Ravenna in his palace at Aachen, including a now lost original statue of Theodoric.[3]

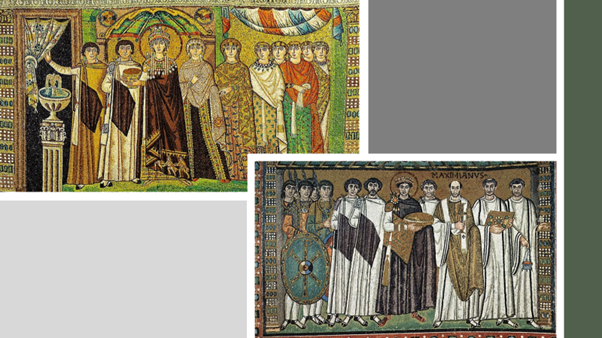

Characteristic of Herrin’s brilliance as a writer of history is the way in which, as she compares the use of the great cathedral of San Vitale, a building originated by Theodoric, with the Aachen Palatine Chapel. There is in this short section a moment in which Herrin imagines Charles seeing and identifying a model for self-making that acknowledges even the trivial glitz of adopting, ‘an unforgettable image of how to display oneself as an emperor’.[4] And at the centre of this metamorphic image in which self and social, religious and political role are united in an image that is one of the key ones of the whole book and is constantly and beautifully revisited, the mosaic images of Justinian and Theodora.

This imperial couple never visited Ravenna other than in this aesthetic-symbolic iconic form, faced each other across the beautiful apse of San Vitale, with only their ecclesiastical representative, Ravenna’s Archbishop Maximianus. And the imperial image is of an Emperor who took charge across an Empire, even parts of which he might never visit and to which he applied a new code of Roman law hereafter called Justinian. That Charlemagne could be both Justinian and Theodoric in his self-image showed how he bridged the actual divisions of sixth-century Ravenna. The real Maximianus replaced Theodoric’s loyal Arian Bishop Victor’s image with his own, leaving only Victor’s feet in the image on which the victorious new Archbishop could stand, in San Vitale to indicate there were ‘new rulers of the city … the distant but all-powerful political leader’.[5]

Taken as a whole those panels unite military, spiritual and courtly medieval values of a nation’s court. Their importance is great. But it is equally clear that Herrin sees their values as stemming as much from a Ravenna of the West, the Imperial imagery of San Vitale finding itself at home with Western aspirations to Rome that were so beautifully symbolised in the art associated to the daughter of Theodosius I, Galla Placidia, educated by Goths. Even Maximianus is associated with a new phase of insistence on a Latin bible rather than the Greek of the Eastern Empire, and therefore with at least the margins of Western hubris.

I learned so much from this book because it does not so localise its history of Ravenna that it misses its lost world significance nor idolise its aesthetics without rescuing the lost meanings of roads in history that led nowhere, in as far as the modern world is concerned, but an oasis of beauty.

For me it is history at its best. I can’t do justice to the insights into the evolution of Roman law, the establishment of western Empire and the hubris of Peter’s Church of Rome. And indeed so many lovely things. It makes me love history as a cherishing of what powerful contemporaneity feels is better lost, forgotten or dismantled.

Steve

[1] Herrin (2020: 387)

[2] ibid: 360

[3] Plate 62 (facing ibid: 379), ibid: 379.

[4] ibid: 371

[5] ibid: 170

One thought on “‘There is a great deal of losing and forgetting about Ravenna as well as physical dismantling, which is also a form of forgetting.’[1] Reflecting on the ways and means of history as a form of remembering the lost body of the past’s being. Judith Herrin’s (2020) ‘Ravenna: Capital of Empire, Crucible of Europe’”