Art Deco By the Sea: Reflecting on class, sex and the arts of the shaped environment. A blog on an exhibition (seen at Laing Gallery Newcastle) & catalogue: Ghislaine Wood (ed.) (2020) Art Deco By The Sea Norwich, Sainsbury’s Centre for Visual Arts.

Exhibitions like this one make an important contribution to how we understand the role of what we call ‘art’ in the way our everyday lives are shaped socially, culturally and psychologically. We could start with basic concepts, for instance such as leisure, pleasure, fun and relaxation. These words are not innocent of social construction across the range of variations in their meaning. They are terms for thoughts understood in the form of images and other sensations – that is, not just by the eye but other senses. Hence the key importance of the part of the exhibitions title, ‘By the Sea’.

That is because the seaside is a means by which concepts like leisure and pleasure changed historically in the minds of great numbers of people with the advent of a less austere notion of the meaning of ‘life’. The meaning of the term ‘holiday’ for instance shifts from the licence to escape toil in the name of Church or God to a right. Hence the frequent references in the exhibition to the Holidays with Pay Act of 1938. The formal and informal social governance of leisure and access to it became by such measures the business of many institutions in complex societies and mixed economies.

Without pretending to be at authoritative about this link, this felt to me as a viewer of both exhibition and catalogue to make connections to the words which network with the architecture of seaside pleasure areas and domains, particularly the advent of the lidos, as a phenomenon of the history of the 1930s. The term Lido meaning ‘shore’ or ‘bank’ in Italian was generalised from its use to identify the seaside pleasures of a isle in the Venice Lagoon by English visitors to identify seaside pleasure areas and beaches. It would be nice to think that this underlay the name of a late nineteenth phenomenon of the pleasure beach, but these were in fact earlier creations, even though this exhibition shows the importance architecturally of the Art Deco additions to the Pleasure Beach in Blackpool in the 1920s and 1930s. Blackpool Lido of the 1930s was one of many such. There is excellent footage from the 1930s of the ‘lido’ (not officially called that but generically identified thus) of Portobello Open Air Swimming Baths.

That film and this photograph show the commonalities of lidos as places for outdoor mass recreation with mock class architecture (the Blackpool Poll was officially called a Coliseum), such as cupolas and columns, the use of such architecture to exploit tiered platforms for viewing and promenading. The presence of such tiers often marked the vertical aspect of art-deco buildings as did stairs that were not only spirals (here probably from French Baroque models) but made to look dynamic so that one might think of them as performing a screw motion. Photographs and paintings of such are legion in this exhibition, though I use a populated example of Mendelsohn and Chermayeff’s De la Warr Pavilion at Bexhill-On-Sea here in order to show the relation of body, stair and in-congruent rails on seeing someone ascend or descend them.[1] The finest example in the exhibition is that staircase placed in the Casino in Blackpool Pleasure Beach.[2]

A prominent feature of the lidos were the tiered platform towers, structures only enabled by the existence of reinforced concrete as a material that acted as diving boards. In fact as in all the examples these were also as properly known as platforms affording a view from and of them and this is exploited in the painting, where the phenomenon of pleasurable viewing is the clear subject. The viewer of such railway holiday posters is caught in the high desire to view the mass s(he) inhabits, like dots below them in a vista that offers itself and is symbolised in the half-returned gaze of an anatomically impossible bathing belle, whose right toe seems visually to touch the water she is, in purely visual perspective, much higher above. She is reduced to body parts and these parts find no whole image, being rather laid out to the view and filling the picture space. Meanwhile the masses below have their own platforms for viewing. It is an intriguing image. The Lido is a domain of the eye in the design shown by Septimus Scott.

But the same idea of viewing platforms outside meant to enable views out towards us feels characteristic of the Art-Deco of the lido. If more examples are required look at the examples of the Funhouse in Blackpool Pleasure Beach.

Now the Funhouse has no external stairs although the experience of the interior involves climbing up and down to moving walkways, slides and other vertically challenging pleasures. This idea is expressed in the layering of the architecture into faux tiers against the flat background of the concrete, almost like tiered viewing platforms, and towers with over-sized platforms dominating their top. Flat backgrounds become a feature of themselves, almost as if a non-supporting wall becomes a static flag or page on which to write or draw (in mock fresco) the pleasures they contain and advertise to those still outside the building. A pleasurable aspect of such architecture is the use of complex or unusual large fonts used to name the buildings on their outside. The Funhouse is a fine example but Dreamland cinema, leisure and restaurant complexes have a similar look.[3]

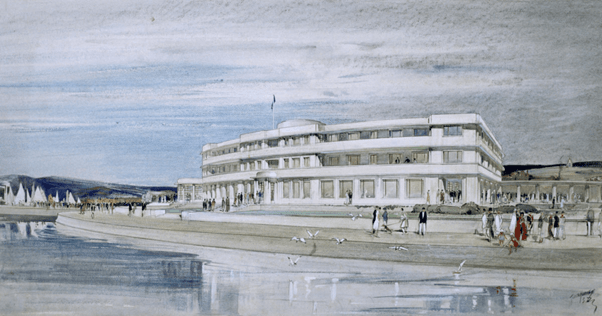

This is even the case where Art Deco work was meant to appeal to a non-mass market as in the case of the Midland Hotel at Morecambe.

This is a venue that enables the rich to view from above the poorer denizens of the mass holiday destination Morecambe at the ‘base’ of the building. Its features play at classical values and forms while not being such, its interior art refined by contemporary masters, notably Eric Gill’s mock-Abyssinian relief sculptural wall plaques. There are the same elevating staircases. But the purpose of the Midland is, unlike the Funhouse, not to invite hoi-polloi in but to exclude them into the background in favour of those linked to Morecambe’s marina and its higher class associations.

Such differences in the representation of subjective viewpoints is examined in Art Deco painting and some examples make rather splendid use of the concept of the desirous, concupiscent or envious gaze. These are two paintings I found to excel over others in this regard. It also points out that the exhibition is brilliant too about transportation modes and their architecture, although I’ve chosen not t consider them in this blog. The first is Leonard Taylor Campbell’s Restaurant Car (c.1935) now stored in the National Railway Museum. Here it is:

This painting manages to dramatise a set of ways of gazing that are not otherwise connected. Thus differences in the gaze of those engaged in the scene as a worker are contrasted with those who engage in it as leisure. The rail steward’s gaze seems to me to dominate as a function of his height in the triangle of eyes which fills the viewer’s right of the picture. Looking between aged male leisure (with opulent book on the table and glossy periodical filling time) and female enactment of being seen pretending not to be seen, this is almost a summary of the class and gender politics of the1930s. The woman is viewed by her husband or lover but is demure to that gaze as to that of the viewer. Only the viewer is offered the gaze out of the windows on the seaside to which we look with longing. This reading is less suspect if we remember that contemporaries compared Campbell’s methods as a painter (of light but I would say of gaze too) of Vermeer.

But a painting that grabbed my attention most was Fortunino Matania’s Blackpool (1937).

I find this intriguing most in its handling of gender. Throughout woman are to be viewed rather than viewer’s. The man sitting on the viewer’s right is sharing a gaze with the viewer, an effect I found quite homoerotic, though not (though I am gay) pleasingly so. The other dominant male figure is alone and leans against the promenade wall. Both clearly look at things we cannot really identify and seem therefore as gazers to have a consciousness that can apparently float free of the otherwise visible scene – one towards the viewer, one merely underlining his isolation from other groups. The women in the scene invite the view as objects. The woman on the stone has a statuesque aspect and reminds of a figurehead or car bonnet figurine, so popular in the Art Deco car. Her appeal is that of the symbol of the healthy mother-figure that, as Ghislaine Wood (2020: 136) shows in the catalogue was not only a feature of eugenic and sporty health promotion ideology in Fascist Germany, citing Margot Bagot Stack’s work on promoting the ‘body beautiful’.

Women are the natural Race builders of the World. It is they who should be responsible for its physique … they are the “Architects of the Future”.[4]

Blackpool is a painting which celebrates those nubile and fertile ‘architects of the world’ in a group on the viewer’s right, caped and muscular and clearly available in that they cluster around one man who looks not at them but at the viewer. Yet her posture and gesture are entirely phallic, the only phallic vertical or diagonal to match the effect on the sky of the painting except for Blackpool Tower. A single woman ascends from beach to promenade and captures our gaze on the left. I find it a remarkable, if not beautiful, painting that politicises pleasure as a function of white nationhood and patriarchy. It is a symbol of the very worst of the 1930s Art Deco and the meaning and power of mass pleasure.

See this exhibition of you have chance. It continues at the Laing Gallery in Newcastle until 27th February 2021. If you can’t, buy the lovely book.

Steve

[1] A purer example photographically in Wood (2020: 35)

[2] ibid: 151 (outside), 156 (inside)

[3] ibid: 56 for exhibition version

[4] Ghislaine Wood (2020: 136) ‘Building the Body Beautiful …’ in Wood (op. cit.)

3 thoughts on “‘Art Deco By the Sea’: Reflecting on class, sex and the arts of the shaped environment. A blog on an exhibition (seen at Laing Gallery Newcastle) & catalogue: Ghislaine Wood (ed.) (2020)”