Some reflections on ‘Waiting for the Barbarians’ Director: Ciro Guerra. Writers: J.M. Coetzee (based on the novel by), J.M. Coetzee (screenplay by). Stars: Mark Rylance, Johnny Depp, Robert Pattinson

… – if I had gone on a hunting trip … , and come back. and without reading it, or after skimming over it with an incurious eye, put my seal on his report, with no questions about what the word investigations meant, what lay beneath it like a banshee beneath a stone – if I had done the wise thing, then perhaps I might now be able to return to my hunting and hawking and placid concupiscence while waiting for the provocations to cease and the tremors along the frontier to subside.

J.M Coetzee (1980: 9) Waiting For The Barbarians London, Secker & Warburg.

Coetzee is a writer who writes about writing and the relationship between readers, writers and the truth. His subject then is often about the kind of gaze and the quality of its attention on text that does not yield its message easily. We should expect then that an audio-visual dramatic interpretation of the text will require text and acts of reading and/or writing to be a feature of the film. And so it is in Guerra’s film. There are many moments in which text is literally focused upon and the only action is writing or variants of reading. Letters are written and read, for instance, between the capital and the frontier administrators that show mutual incomprehension.

There are advantages, the magistrate finds in the words I cite above in skim reading, in letting one’s attention wander. We don’t in such reading find any horror that oppressive practices like torture hide under words like ‘investigations’. We enable ourselves to survive and live on by being careful not to notice what is under our eyes, though under some slight cover.

This was the world of Apartheid South Africa where government report after report need not hide some of the oppressive activities of the State but merely rename them in a manner that identifies an activity of governance. Think of Israel in the Gaza strip or the ‘acts of rendition’ in which the USA and Labour governments colluded, and will again perhaps in the new attitude to ‘security measures’ in Keir Starmer’s Labour (the jury is still out on the latter). If we do not look we do not find. Hence the act of censorship can be nuanced, allowing out certain truths under a veneer of renaming, suppressing only those on which we dare not look.

In the scene when Robert Pattinson playing a junior officer under Joll explains to the magistrate what the meaning of the action is (in the still below) is little more than words that identify no actions and justify the utmost violence under the look of authority (desks, books on library shelves and immaculately worn uniforms). He says Joll: “is taking actions to correct the situation you have allowed to develop here”.

The actions go undescribed in these words as does the situation requiring redress or the actions which had been allowed to develop. As the magistrate knows there is in fact no situation, no danger from the Barbarians, other than that in the imagination of those who rule the Empire from its central capital but know nothing of the real frontier or border.

So the novel and the film feature ways in which our vision might be masked or lost – by blindness, pretend blindness or dark glasses (crossed in the film with an X over Johnny Depp’s representation of Colonel Joll’s inscrutable forehead. Dark glass not only change the vision of the wearer in some ways, it hides our ability to see and assess the gaze of the wearer. And Depp acts this kind of mutual occlusion of vision with characteristic brilliance, as we see perhaps in the stills below.

And if we are to focus on how to see, the film has to co-operate in the endeavour. This film with script by Coetzee employs styles of acting whose sheer brilliance lie in showing both what behaviour shows and what it tries to hide from showing. It creates the mannered and ‘laboured’ pace the film and gives it depth, so that we are continually on the look out for the screened meaning of visual effects and for that which is there but hiding in plain sight. We need to look in at least two, but probably many more, ways. Coetzee elsewhere speaks of being a writer working in an air of the suspicion and mutual distrust required by oppression. Acts of mutual censorship include those of both the censoring authority and the writer self-censoring before being actively censored, in oppressive regimes. Such writing is:

… like being intimate with someone who does not love you. with whom you want no intimacy, but who presses himself upon you. the censor is an intrusive reader, a reader who forces his way into the intimacy of the writing transaction, forces out the figure of the loved or courted reader, reads your words in a disapproving and censorious fashion.

Coetzee, J. M. (1996: 38) ‘Emerging from Censorship’ in J.M. Coetzee Giving Offense: Essays on Censorship Chicago, University of Chicago Press.

We see this strange relationship described between the magistrate himself and the blind barbarian woman he saves but then unknowingly and unseeingly abuses so that he cannot see she hates him for his appropriation of her. The magistrate finds it impossible to divorce love from collusive ‘concupiscence’, as Coetzee calls it above. This abuse in fact plays the same game of oppression of the barbarian ‘races’ as that played more obviously by Joll. Joll tells us that war in the film, for instance, is ‘all about’: “…compelling a choice on someone who would not otherwise make it”.

It is about abuse of the eyes. Yet exactly what kind of torture occurred that removed central but not peripheral vision from the blind barbarian’s eyes is never clear. ‘What have they done to you,’, the administrator, so brilliantly played by Mark Rylance, say in this scene, as he continues to dominate the limit of her vision in another way, kindly oppressive but oppressive, nevertheless.

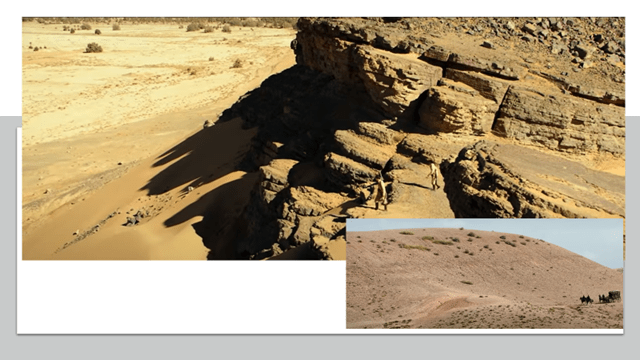

Human civilisations and the paltriness of their surveillance of, and transport over, the land that does not belong to them are in this film swamped by the sheer space of visions of it offered by the film. Land and space of which there are no reliable written maps, but yet of which barbarians, always on the move know every inch. The ‘civilised’ rely on poor narrative reconstructions based on ‘tales by travellers’ and are and will be defeated by such thin knowledge. This is the perception that the film best offers: something beautiful but wild and untamed, only to be known by living on, rather dominating, it with our civilized tools of books and maps.

It’s a great film but it needs seeing more than once. I have to see it again on DVD. Do the same (Region 1 only it seems though – so adapt your player if it’s R2).

Steve