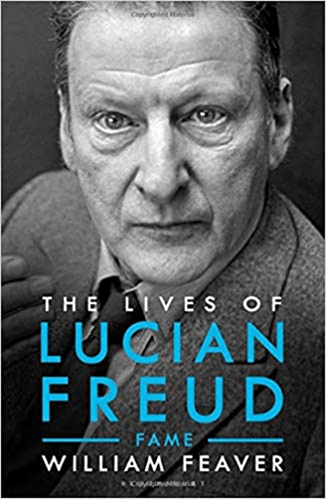

‘We are all queer. If you say you are not you are outed’. Volume 2 of a life of Lucian Freud: William Feaver (2020) The Lives Of Lucian Freud: Fame London, Bloomsbury.

Note on Volume 1 appears in: https://stevebamlett.home.blog/2019/09/16/first-reading-of-william-feavers-2019-the-lives-of-lucian-freud-youth/

In commenting on Volume 1 of this biography I tried to define the way in which we must understand the ‘queer world’. I wanted to look at queerness both as Freud and contemporaries talked about it and as a bridge to queer theory readings:

It is queer because it escapes certainty of interpretation and categorisation and I think the sexuality of the period truly to have been more like this than is presented by some witnesses.

That helps us, I think, to make at least one interpretation of the quotation from Freud in my title, in which Freud reviews his relationship as an artist to John Craxton and that time in which they shared a studio: ‘We are all queer. If you say you are not you are outed’.[1]

At one level Freud is denying he is gay and, at another level, showing that his sexuality is already queered in precisely the way it resists being either outed or internalised in any simple terms. It describes his heterosexual relationships, including to his biological offspring, as well any putative or secreted relationship. As Francis Bacon put it, once their relationship had soured: ‘”She’s left me after all this time,” he said. “And she’s had all those children just to prove she’s not homosexual”’.[2]

The grandson of Sigmund Freud can easily be seen as the heir to the notion of genetic predisposition to bisexuality in human being proposed by psychoanalysis. But Lucian Freud’s queer sexuality is not attributed to such a binary explanation. Feaver’s second volume comes near to explaining, perhaps semi-explicitly, why. Sexuality in Freud’s art can’t be reduced to the stories of his temporal affairs with so many women and those who love his art work know it emerges most forcefully out of a complex relationship between artist and model; the most enduring as well as time-consuming feature of his interactions with otherness. Although he judges it a fanciful statement, Feaver’s book does evidence why it is appropriate to think about Freud’s characteristic as a painter, and of his desire to paint flesh – usually but not always human, as the things which happened when someone or thing ‘sat’ for him:

Sitting was a ‘a most special’ unique and privileged experience: ‘there is an enormous sense of kindness and thoughtfulness which envelops the person in front of him’.*

‘I like to think I can work from anyone’. …[3]

*The quotation is from Sally Clarke’s Lucian Freud Remembered. Note 6 for Chapter 35 on p.539.

The relationship between artist and model(s) is, after all the best explanation of desire in Lucian Freud. It is a constant play between perceptions of depth and surface, light and shade, colour and tonal variation, even in the relationship of flesh to objects and its own ‘objectness’, as it metamorphoses through the artist’s subjectivity into something enduring, at least relatively. ‘I am not an object’, Freud said on his death to a child who tried to touch him. However, so much that he touched must have felt so objectified in the process of being enveloped by the subjective relationship between themselves and the artist. Most of his paintings ask us the question: ‘what is the thing I look at and what are its boundaries?’. To ‘work from anyone’, would be to not differentiate one thing from its properties and Freud’s sitter do that, neither personal nor typical, they yet avoid names and the social markings of clothes most often.

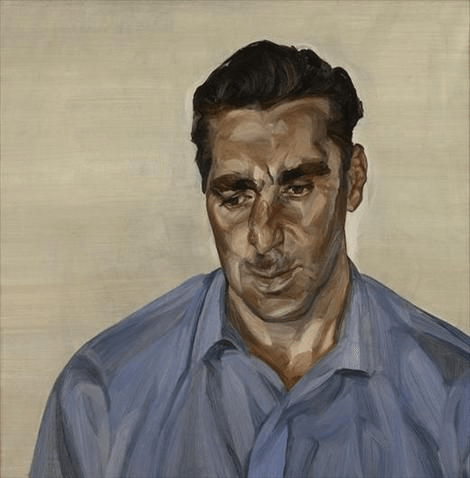

What are personal characteristics in Freud’s ‘subjects’, so easily transforming into quasi-objects (if clothed into their clothes as objects– such as The Man in A Blue Shirt (1965) of George Dyer. Dyer’s shirt queries the desire that made him the object of Francis Bacon’s fascination: a query clearly shared by Freud, whose art pulls apart the shirt to the shadowed flesh, to which Dyer’s gaze almost descends.

These characteristics or attributes (personal and social) of ‘sitters’ include familial bonds and identity, sex/gender, unity or multiplicity (the games played with the painting Sunny Morning – Eight Legs 1997 for instance where legs and bodies appear merely to be counted rather than be personified), flesh, body and its defining characteristics (especially in fat people), boundaries in the relationship to setting?

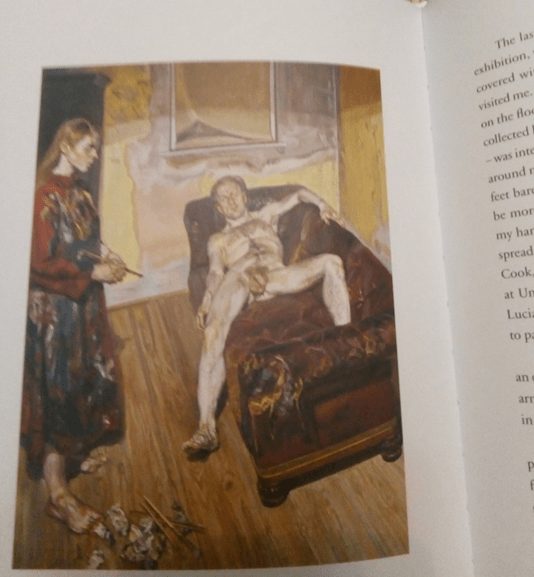

They are all of these things but their relationship to artist and setting is entirely liminal, in the act of emerging as something else, as in the wonderful portrait of Celia Paul (Painter and Model, 1986-7), herself painting the model and friend of both, Angus Cook.

Freud’s queer sexuality is those sets of complex relationships in my view and is read in the transformations of Leigh Bowery, Sue Tilley as well as his own artist lovers such as Celia Paul, other lovers, children and casual sitters and people employed or learning (David Dawson). Aren’t they all transformed by the painter’s desire and their relationship to their settings, including other forms of life or animation (like paint squeezed out by feet) in their vicinity.

This second volume of the biography continues to illuminate because it too uses Freud’s own words like the first volume, so often. They are woven into the fabric of other people’s words and the writerly friend’s critical and other perceptions but they dominate the piece so that we know exactly why the last chapter is called ‘I am not an object’. Feaver weaves those words from their context into an analysis of Freud’s life-project and this is stunning. I will leave you to find the passage yourself.

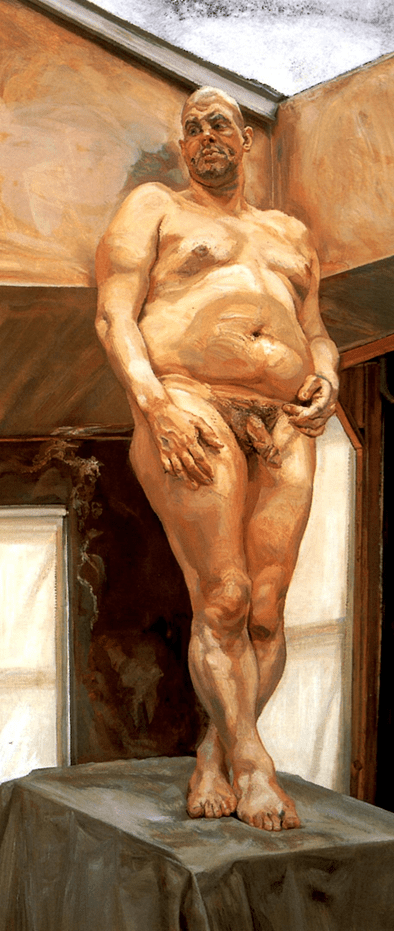

In looking at Volume 1, I said I thought there was an no deep critical analysis of the paintings. I may have been wrong but in Volume 2 that is certainly not trye. Life, art – and the objects and subjects that are their common elements as well as the difference that make leaving a work as finished as it will be, art and not life, are all comprehended. There are moments of sheer critical brilliance – such as when he compares Sue Tilley as a subject to Leigh Bowery. He suddenly weaves in Leigh’s knowledge of his own HIV status and how Leigh willed more into his self-presentation. We see Freud as consummate in bringing together those contradictions, in which Feaver’s every word is so thoughtful. Look for instance at the brilliant use of the word ‘spectacular’ here, which blends ideas of spectacle and the wish to look great with critical precision. A spectacle is both to a thing to be desired and a thing that places what is seen in a harsh light:

… these spectacular helpings of body weight and disposition, complement Leigh Under the Skylight (1994), the painting that proved to be Leigh’s last stand, a salute to the statuesque performer and former Burger King assistant manager, raised up and cast as a caryatid or …. a Samson readying himself to bring the house down.[4]

There are so many levels of ambiguity and fun, loftiness and reductivism here. It is in the very writing.

And there are longer analyses of individual works that illuminate, too many to example but one.

If I had to pick a fault, it’s one I felt less in Volume 1 than in Volume 2. Biographers or partial biographers of Freud often make much of the evidence of their own acquaintance – Geordie Grieg, Martin Gayford, David Dawson. Some, particularly the latter who thought of himself, according to Frank Auerbach as ‘Lucian’s other half’ as he provided physical care, support as well as being the major model, have that undoubted moral right.[5] ‘Villiam’, as Freud calls Feaver throughout the biography is one such too. This is particularly evident in the late stories of the artist’s dementia and Feaver’s role in maintaining Freud’s social life up to death. That privilege of observing and interpreting may seem galling to the family subjected to Feaver’s gaze as the artist dies.

Notice this exchange between Dawson, whose 2011 conversation with Feaver is cited, and Feaver’s supposedly more benign interpretation of the behaviour of the Painter’s daughters:

‘…. The daughters come around and are obsessed with reading to him’. A sensible thing to do in that it relieved the reader of the strain of making conversation and, being read to, the patient could doze. Better poetry and Middlemarch than faltering bedside chat. …[6]

The two men here interpret the daughters in a way that allows them not a word in their defence should a reader find their response as both belated and compromised, which, though it could have been, is merely intuited in male conversation about the feelings of women for whose actual motivation we have little other evidence. But without such interpretation, there could be no true biography that is readable and relevant to the humanity of all of us. Please read this book. It is a monument to Lucian Freud.

Steve

Other Freud material blogged (if not otherwise indicated below:

[1] Cited Feaver (2020: 174)

[2] ibid: 99.

[3] ibid: 497.

[4] ibid: 304

[5] ibid: 509

[6] ibid: 512

11 thoughts on “‘We are all queer. If you say you are not you are outed’. Volume 2 of a life of Lucian Freud: William Feaver (2020) ‘The Lives Of Lucian Freud: Fame’”