‘Writing is routinely described as ‘creative’ – this has never struck me as the correct word. … To plant a bulb (I imagine, I’ve never done it) is to participate in some small way in the cyclic miracle of creation. Writing is control’.[1]

‘Intimations: Six Essays’ (2020): Zadie Smith. London, Penguin.

How refreshing it is to read a writer who emphasises the unfashionable and hard aspects of her craft, such as the resistance and difficulty involved in writing. It’s a kind of work where we attempt controlling the uncontrollable. An ever-ongoing process in which: ‘We try to adapt, to learn, to accommodate, sometimes resisting, other times submitting to, whatever confront us’.[2]

Whoever said learning was easy. Of course it is not. It confronts us with the inadequacy of old conceptions and we can choose, if we must, to live on and in these old conceptions. Or we can tread into those liminal spaces where we have no guide and then try to control the direction and paces of our course to a destination of which we can know very little except that it too will one day become inadequate to our needs.

To write is to learn and to ‘never relax….’.[3] Because however skilfully the tension of experience is released, by the alert imagination or a clever masseur, the need to control and to tighten up sets in. Take Ben the masseur, for instance:

His hands are incredibly strong. He takes each knobble of the spine and works around it, freeing something (what?) and the effect lasts about forty-eight hours before whatever was free begins to knit itself back together in pain and ….[4]

I like the fact that this sentence doesn’t end there. It contains its own contradiction. As it tries to relax, it wonders quite what (‘(what?)’ it was relaxing and turns in on itself again seeking an answer. As it proceeds so the sentence rigidifies the very things it wants to free. They must accept the pain of that constriction and rigour as either a hopeless desire as in this sentence or as a fact: ‘Writing is control’. Ben’s ‘head and face’ may be ‘optimistic in construction’ and he himself, indeed look: ‘like optimism’. However, the act of freeing experience is never complete without some acknowledgement that, if you cross the street and look at Ben without him noticing, he is bound up in the art of control of something much darker, that is even more prominent under the economic conditions of lockdown:

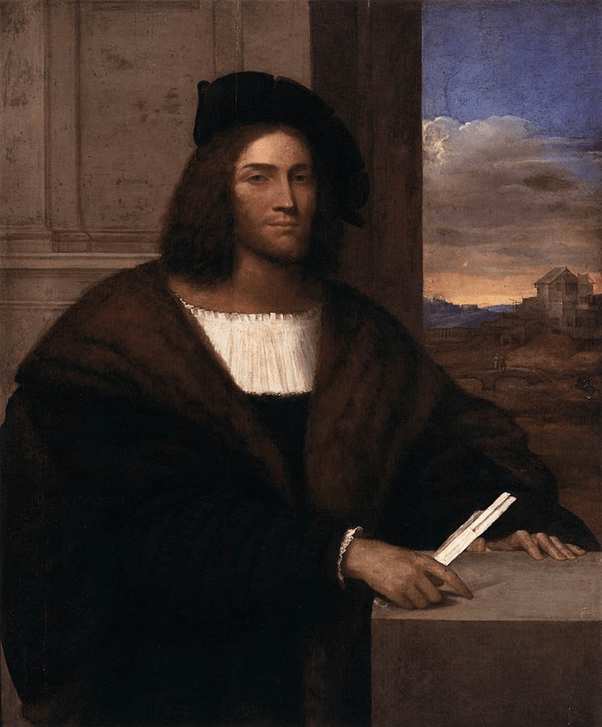

… standing anxiously by a hand-dryer, looking out on the street, his optimistic face transformed from the cartoon I thought I knew into a stern portrait of calculation and concern, at once mercantile and intensely humane, backlit like a del Piombo, and evidently weighed down …[5]

You need to look at a Sebastiano del Piombo (like the one below perhaps) to get the full force of that. A controlled act of art is controlling the man who is himself the image of control and calculation but must look and preach a relaxation from control. it is the human condition. Sometimes I like to say it is thus under capitalism but perhaps it is thus under many known regimes of political organisation of scarce resources.

Of course Smith is too intelligent to let unrestrained capitalism, like that of the Trump era, off the hook. Her beautiful short essay, The American Exception, on the advent of Covid-19 into the American dream is savage, speaks in a beautiful and just way about the Trump phenomenon. It speaks hopefully of the withering of the competitive and aggressive means of becoming ‘great’ in the world or elsewhere. Trump restored to zombie life such a deathly image of the world and what was important in it: supremacy of the fortunate, aggressive self-interest, and war in the name of those things. But; ‘Death has come to America’, in the form of a pandemic now:

What was once necessary appears inessential; what was taken for granted, unappreciated and abused now reveals itself to be central to our existence. strange interventions proliferate. … people thank God for ‘essential’ workers they once considered lowly, who not so long ago they despised for wanting fifteen bucks an hour.[6]

So like the USA and so like the United Kingdom! But the period between infection spikes in the UK showed how chirpy was zombie high-finance capitalism in re-asserting its methods of merchandising illusory ‘freedom’ from controlled regulation and the state’s mitigation of the costs of selfishness. Zadie Smith ends that essay by showing how the choice of Churchill as a source of war imagery and rhetoric can and need be replaced by another model: Clement Attlee. She quotes him thus: “…. Why should we suppose that we can attain our aims in peace … by putting private interests firsts?’

And though, she also examples the successful example of state health-care in Europe as a lesson for Trump’s USA, and unfortunately now necessarily for Boris Johnson’s UK, that applies to other areas mentioned by Attlee, such as ‘food, clothing, homes, education, leisure, social security and full employment for all.’

I would extend Zadie Smith’s insistence that the North American insistence that there, ‘may be many areas of our lives in which private interest plays the central role’ is questionable. I’d expand it to this business of writing. Private interest is like a kind of writing that doesn’t examine its public role, either in its obligation to readers or to those that are subjected to the function of writing even though they may not be its readers. The latter are its ‘subjects’ so to speak.

My favourite essay in the collection is ‘Suffering like Mel Gibson’. It addresses whether an artist has the right to find an equivalence in their experience for examples of individual suffering otherwise outside their experience. It is for the writer to address why it is necessary to convey the absoluteness and ‘reality of suffering’, such that in:

… that next painful bout of video-conferencing, (…) you don’t roll your eyes or laugh or puke while listening to what some other person seems to think is pain.[7]

I have seen this in multi-disciplinary conferences about service users who are, in one way or other, expressing the absoluteness of their pain. For a true writer doesn’t make the problems of a privileged audience easier; they have to expose those people to what absolute pain is.

Hence Smith’s ‘intimation’ is that we only really ever scratch the surface when we use a word like pain. In privileged persons pain it’s little more than experiencing a ‘bout of video-conferencing’, a descriptive term for the excruciatingly unpleasant. Likewise on twitter we boast of rolling our eyes (or collecting a meme to display) or find a ‘puke’ emoji. The reality of visceral pain, that makes the young woman mentioned in that essay kill herself is harder to contact, less absolute unless someone like an artist makes us feel it.

Likewise with mental illness which Smith effortlessly but suggestively points to in her essay A Provocation in the Park. Writers should bring us near to contact with these very real things. Her sentences play on the edges of those real things, always controlling and regulating the fact that we know they could happen and are coming nearer to us than our platitudinous sentences think. As in this example from her intimation on the unplanned closeness of things we push usually to the back of our mind: ‘That my fear is stronger than my desire – including my desire to self-harm’.[8]

And if anything the COVID-19 crisis used in this essays as a revelation that art has responsibilities as well as being ‘Something to Do’.[9] And those are social responsibilities. Once all of us have ‘time’ on our hands through a furlough scheme, for instance, we become like artists. But that time is not and never has been ‘free’ time but an opportunity to:

(… create a collective demand to reassess and reconfigure, as a society, how we protect the rights of those whose work exists only in the present moment, without security or protection against unknown futures, …). The rest of us have suddenly been confronted with the perennial problem of artists: time, and what to do in it.[10]

There has to some regulation and control and that is why writing demands it. ‘Free’ time is a myth. Writers know that all of the time. If they don’t use it to raise questions about ‘the rights of those who only exist in the present moment’, including non-readers, they abuse it and themselves. Because after all as the intimation on Darryl realises about a word we commonly use but rarely elaborate: ‘Identity … as the form in which you’ve chosen to expend your love – and your commitment’.[11] As a clarion call to an engaged literature it has more style and more push than do Sartre’s novels. Will we buy it? I hope so.

Steve

[1] Smith (2020:4f.)

[2] ibid:5

[3] ibid: 39

[4] ibid.

[5] ibid: 41

[6] ibid: 14f.

[7] ibid: 35

[8] ibid: 81

[9] ibid 19ff.

[10] ibid: 21f.

[11] ibid: 79

Hi Steve Very interesting my next blog is that it’s on social media

LikeLike