‘The cold renunciatory beauty’ (1933): A poem by David Gascoyne

The cold renunciatory beauty of those who would die

to hide their love from scornful fingers of the drab

is not that which glistens like wing or leaf in eyes

of erotic statues standing breast to chest

on high and open mountainside.

Complex draws tighter like a steel wire mesh

about the awkward bodies of those born under shame,

striping the tender flesh with blood like tears

flowing; their love they dare not name;

Each is divided by desire and fear.

The young sons of the hopeless blind shall strike

matches in the marble corridor and find

their bodies cool and white as the stone walls,

and shall embrace, emerging like mingled springs

onto the height to face the fearless sun.

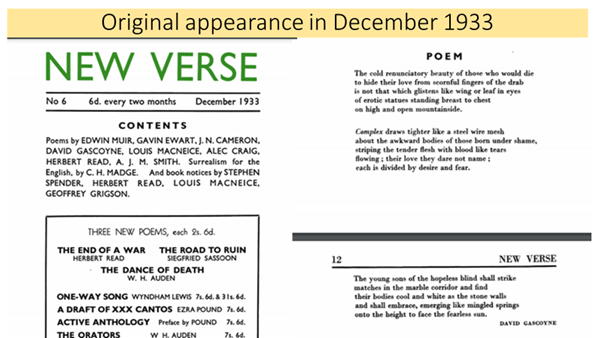

It’s important to get the dating of this poem right because Roger Scott’s Edition of the New Collected Poems does not. That book dates it in about 1936, just prior to the collection of poems that Gascoyne acknowledged as surrealist of 1936. There are odd things going on with dating in the text and notes of Scott’s edition that may be a result of uncorrected errors.[1] It is clear that this poem had in fact been written sometime before December 1933, because it appears in the edition of Grigson’s Modernist magazine New Verse for that month (see figure above). Pedantry about the date can be justified by Gascoyne’s special affection for the year 1933 which he calls his ‘Annus Mirabilis’.[2]

That appellation owed much, he says in an Introduction his Collected Poems, to Geoffrey Grigson’s ‘small, adventurous, and soon influential periodical’.[3] The influence is also clearly in that passage associated to the excitement of the dawn of what was considered the dawn of a specifically English surrealist movement and the first book collection of our poem was indeed in a 1936 collection usually described as surrealist in intention, Man’s Life is His Meat. But 1933 was turbulent in many ways as the long treatment of it in Robert Fraser’s excellent biography of the poet shows.[4] In that year, Gascoyne went to France, becoming acquainted with major French surrealists, both poets and visual artists.

It was a year though not only of initiation into artistic movements and the debates from which they were born and which they further developed. Fraser’s biography stresses that it is important not to equate this Paris visit, and the taste for that visit he developed in the radical company of David Archer and ‘his flair for making young male friends’.[5] Archer’s radicalism focused on a London bookshop and a group of left-leaning and often decidedly bisexually orientated set of such young men, including Philip Toynbee, Michael Redgrave and Geoffrey Grigson. Here the young men discussed, amongst other things, Rimbaud, himself an index of interest of for both budding surrealists and men with fluid not necessarily binary sexualities.

Hence I think we should never, as most people do, merely emphasise the surrealist component of the Paris trip without realising that there was much more at stake for young men in Paris than a taste for the concept of automatic writing, writing that flowed from the unconscious with as little mediation from logic, reason or mimetic form as possible. One of the benefits of that concept anyway was poets could explore suppressed cultural, economic, social and psychological drives. Fraser’s view that artistic endeavour in Paris in 1933 ‘transcended all -isms’, including a pure form of surrealism if any such thing existed.[6] With left politics Gascoyne could visit and study literary travellers like Hemingway and learn of an equally important movement to Surrealism at the time, New Romanticism of artists such as the extravagantly queer Pavel Tchelitchev.

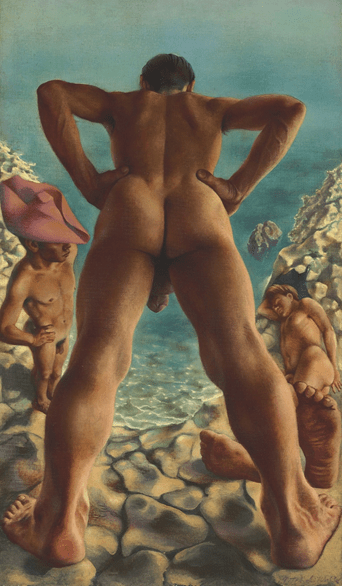

He fell in love with a woman, Kathleen Hime, but also on one of his dates with her took time out to follow up an introduction to Tchelitchev’s American lover, the poet Charles Henry Ford, who appeared so openly reproduced amongst sets of male nudes in Tchelitchev’s work. Though it was later, the best example is the picture of Ford in Tchelitchev’s Bathers, where the oft used body of Ford can be seen and the queer context read. Similar pictures (if not so homoerotically detailed but clear enough) had appeared in Herbert Read’s Art Now.[7] What Gascoyne discovered in France was then not only surrealism but a queer culture in emergence, that was to underpin his open (in his Journals for instance) expression of bisexuality throughout his life.

In an interview in 1991, Gascoyne insisted that in remembering this very Paris trip, he thought of himself as ‘essentially bisexual actually’, although insisting ‘the heterosexual part has not been successful’ throughout his life, including his later marriage.[8]

Now the poem we are interrogating in this piece is often thought of as an example of ‘automatic writing’ in the Surrealist tradition with characteristic confusions of the animate as living or dead, and of internal and external landscapes (mountainsides and marble corridors) or internal or externally observed characteristics of the body (flows of blood or tears on the surface of the flesh). However, the poem does not strike me as displaying the unconscious but rather an open and conscious but repressed or secreted sexual landscape. And with this goes an entirely bisexual or queer non-binary sexuality. Look for instance at the way the ‘erotic statues’ are ‘standing breast to chest’. There is a cultural tendency to pull those two words referring to the frontal torso into different areas of gendered association but in truth (and in anatomical terms) neither is gendered. The result is that the lively (‘wing or leaf’) embrace of these dead statues is neither heterosexual not homosexual but always either or both.

Moreover, it is unlikely that Gascoigne in 1933 would not expect his audience to recall when they heard of ‘their love they dare not name’ (rhymed of course with ‘shame’), Lord Alfred Douglas’s poem with the lines, ‘the love that dares not speak its name’, that was used in Oscar Wilde’s indecency trial. Even at the time, it would have been clear that Gascoyne’s line was as much a euphemism for homosexuality as a reference to closed or hidden sexual liaisons of any kind. Similarly the term ‘complex’, used uncomfortably without an article clearly references the psychoanalytic use of the term to identify ambivalently charged and driven behavioural and emotional traits, which appears to describe something repressed.

The final stanza concentrates entirely on the ‘young sons of the hopeless blind’ and surely counteracts the negativity, shame and repression forced on those ‘sons’ in, by using the homophone, ‘sun’, to indicate a movement to sexual self-awareness of men amongst other men, other ‘sons’:

on to the height to face the fearless sun.

This is an early poem of a good poet but it is not in itself a good poem. It suffers from an over-abstraction and its pictures are not so much unconscious of meaning as too forced in the abstract meanings to which sometimes those over-abstract images tend. But as a poem of ‘coming out, ‘emerging like mingled springs’ in which the surface boundaries of bodies blend into a new reality it is beautiful. If we really valued queer culture, we would value this poem. Its aim is to combine contradictions like soft and hard, pain and love in one ‘Complex’, that is not entirely the signal of repression but of something yet to be widely understood in the culture. And the repressors here are not seen simply as evil but rather, and maybe it is more damning, as a mix of scorn and commonness (‘scornful fingers of the drab’). In 1933 Gascoyne is trying to create a new socio-cultural and sexual reality.

Steve

[1] Gascoyne, D. (Ed. Scott, R.) (2014: 45f. for poem) New Collected Poems London, Enitharmon Press. For instance, the 1936 collection Man’s Life is His Meat is dated 1932 in the notes on p. 377.

[2] Gascoyne’s ‘Introductory Notes’ to the 1988 edition printed ibid: xxviii.

[3] ibid.

[4] Fraser, R. (2012) Night Thoughts: The Surreal Life of the Poet David Gascoyne Oxford, Oxford University Press Chs. 4-7 swim around the year 1933.

[5] ibid: 51

[6] ibid: 64

[7] ibid: 65f.

[8] ibid: 429