‘The water was cold but it soon warms up when the boys are made of sunshine.[1] How queer is the love of heterosexual boys?: Andrew O’Hagan (2020) Mayflies London, Faber.

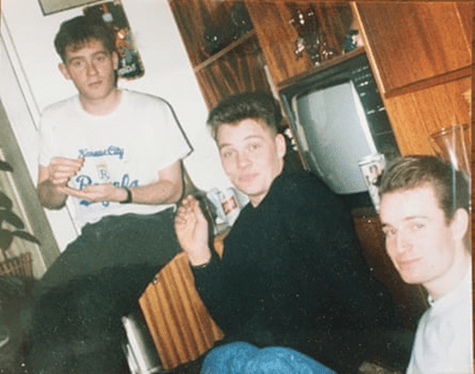

Mayflies falls into two parts, the first set in Summer 1986 and the second in Autumn 2017. It tells the story of an interrupted relationship between the narrator and Tully Dawson as teenagers and the as heterosexually married adult men. Yet that fiction aside, it is well known to be based on the author’s relationship to a friend, called Keith Martin, whose death from cancer prompted the novel’s elegiac mode and change of mood from the period of hopeful achievement and escape from a working-class past to a present circumscribed by a more comfortable middle-class married life.

The mood change between those parts might be set by the change in season between them, but there remains the sense that a gap of 31 years exists in which there have been other distances made. The last sentence of the first part is quoted in the title. It relates to Tully and the narrator (affectionately in the novel called Noodle or Noodles) in a roof-top swimming pool, housed in glass, with Tully having succeeded in persuading Noodle to join in the cold water. Arriving at the pool, Tully quotes James Cagney’s character, Arthur “Cody” Jarrett (‘Made it Ma! Top of the World’) from the 1949 film White Heat.

Cody shouts the line Tully echoes as he blows up a huge globe-like gas tank on which he has climbed to escape capture after a robbery. His elevation and achievement which mirrors the use of ‘top of the world’ earlier in the film, being his death. It s an auspicious moment in which to leave Tully and Noodle in the novel, since it links aspiration from lower class origins to dreams of being some kind of contender in a world of clear class distinctions.

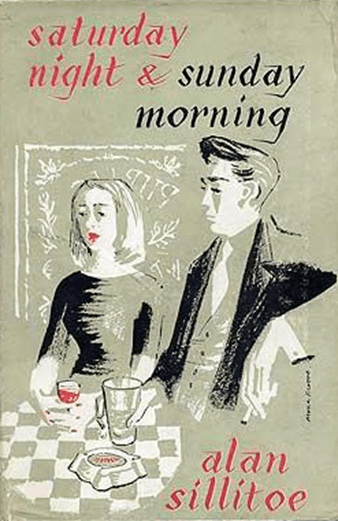

By the end of the novel Tully, a young man ‘who impersonated Arthur Seaton from Saturday Night Sunday Morning’ builds a myth of himself based on that myth of an alienated, marginalised but striving working class man.[2] And the striving is striving, as in O’Hagan’s first novel, to leave behind in class, status and time their own fathers. Noodle aims to ‘divorce’ his parents and is adopted spiritually (which means in class terms) by his English teacher making way for his rise to become a novelist and journalist and like her plying a ‘trade in sensitivity’, much like O’Hagan.[3]

Tully’s relationship with his Dad has a deeper ambivalence and is tied to notions of loyalty, and acceptance of the limits of the life of a former miner. Both Dad and son have green eyes.[4] The tension between them pulls them apart whilst emphasising a deeper unity. Noodle compares his aimed divorce, as he lays on a double-bed with Tully in a furniture shop, to Freud’s version of Sophocles’ Oedipus. Tully is unconvinced. This contest is about men who win their manhood in competition with the Father and all that stands for – a man whose world is disappearing together with historical changes in the world of both work and the accessibility of much wider spaces. Tully says his Dad:

“… blames me for being younger than him. Blames me for the Miners’ Strike. Hates me being in a band. He resents us for wanting to go places and I can’t speak to him and now he’s dying”.[5]

That men die and that the circumstances which define their manhood also pass from history is the deep ambivalent heart of this novel. It is an elegy for manhood and for definitions of manhood. It is deeply significant that the boys play out this debate in a pastiche of two men buying a bed for their mutual use.[6] It is one of the many ways that playfulness is used to queer the relationship between men, without ever intending to indicate sexual union. Look for instance at this characterisation of the young Tully Dawson.

At that time, he had the kind of looks that appeal to all sexes and ages, and his natural effrontery opened people up. … He had innate charisma, a brilliant record collection, complete fearlessness in political argument, and he knew how to love you more than anyone else. Other guys were funny and brilliant and better at this or that, but Tully loved you. …[7]

There is ordinary irony here which belittles the felt seriousness of what teenagers mean when they talk about ‘love’ in the beautifully timed reference to Tully’s ‘brilliant record collection’. This rather trivialises what these boys mean by loving each other just as does Tully’s singing a Glasgow pub song with, ‘his eyes closed and his hand on his twenty-year-old heart’. It’s irony because we do not need otherwise to know that the hear that the heart clasped by his hand, very bodily, is only 20 years old. Other elements do not use these markers of irony.

In the initial description of Tully above, love becomes something known by its existence in behavioural and emotional interactions rather than in objects of knowledge or merely having better skills in things. And who says these looks ‘appeal to all sexes and ages’. This is not narration borrowing young Noodles’ point of view, it is an emergence of the adult writer in his own prose as a development out of his past life as Noodle. We can say as often as we like that this novel is not about embodied love but mimes the experience of a trivial teenage period of practice of loving but it does not seem like that to me. So, if not sexual in a very thin interpretation of that word, it is about love felt in and with the behaviours of the body.

At one point, which I can no longer find, Tully kisses Noodle on the lips, but there are plenty other instances of love exulting between the bodies of developing men. As he invites Noodle to stay with his parents rather than his own, he, ‘leaned over and kissed me right on the forehead’.[8] Though they try out nights with women that are clearly desired, Tully’s ‘best night’ of his life shows in the ‘huge’ eyes he points at Noodle whilst, ‘leaning into’ him and then clasping him ‘round the neck’. Both boys embrace a changing world and will go: ‘All the way’. [9]

The novel plays with the queer possibilities, the possibilities outside the heteronormal, whilst never representing them directly. The very next chapter after this clasp and mutual vow between the lads is followed, merely contingently it would seem as far as the boys are concerned, in a ‘gay bar’: ‘Limbo told him every man should be just gay enough’.[10] Tully’s sexual adventures are more literary than real. He plays with the notion that he is, ‘familiar with the literatures’, in order to justify an entirely stereotypical notion of what nurses are – they are female for instance – where the literature leans much upon the scripts of Carry On films.

When Tully really wants life, its context is intensely queered, without the validation of his conscious wishes. In the chapter that starts in a gay bar, uses the significant term, ‘CHEEKY BASTARDS UNITED’ first spoken by the drag queen in the club, Tully seeks more of life and he ends up, with Noodle, in the pastiche of White Heat I’ve already mentioned.

It was his idea: I was drooping, but for Tully the night could not be over. he wanted further adventures, more time, more everything, and he liked the darkness in the marble halls. We found a huge, weird space at the top of the building, a whole room under glass with a swimming pool.[11]

Tully’s desire for more (of everything) impacts most on Noodle Both boys ‘are made of sunshine’ and their bodies warm together the very cold water of the pool. The bodily sensuality of this is undeniable. We are in weird spaces that go beyond the norms followed otherwise and in their conscious chat in the novel.

Similarly when both men are married and elevated in class (Noodle significantly more than Tully who had to eke out his future by night school learning and is a teacher), the significance of the relationship painted in the teenage section is a bond between men that is often interpreted as competitive with heterosexuality. The contest often takes the form of feelings of exclusion of women from decisions about life bound up in a kind of inexplicable queer romance. The latter in the novel serves the heterosexual bonds completely by the end of the novel but not without deep impact on the lives of the women in the novel that needs to negotiate male bonding and its power.[12] Here again the text is played over with queer potentials, although often in memories, as when Tully circles a male gay lonely heart advert: “Any port in a storm”.[13]

There is also an attempt to place male bonding as a passing phase in the description of Tully’s wedding., in relation to Goya’s 1778-9 painting, Boys Playing At Soldiers (below).

Goya’s painting shows boys playing adult male roles that reveal in them what is solely a matter of play-acting but that also seems to show how emotions such as mischievous envy and admiration belong to young hearts that do not age. Seeing a reproduction of the painting in the marriage venue, Noodle ‘felt it must have waited for us all our lives,…’.[14]

This enigmatic placing of the picture would seem to render ironic the queerness of Section 1’s embodied feelings and thoughts, once seen in the framework of heterosexual marriage. That framework is described prior to this quotation. Marriage involves Tully and Noodle, ‘knocking on all the doors of the past and running away’. But if Anna dominates the beautiful onward description she , ‘like a cinema bride’, her appearance almost typifies a stylistic reproduction of heterosexist marriage motifs in literature such as Spenser’s Epithalamium.

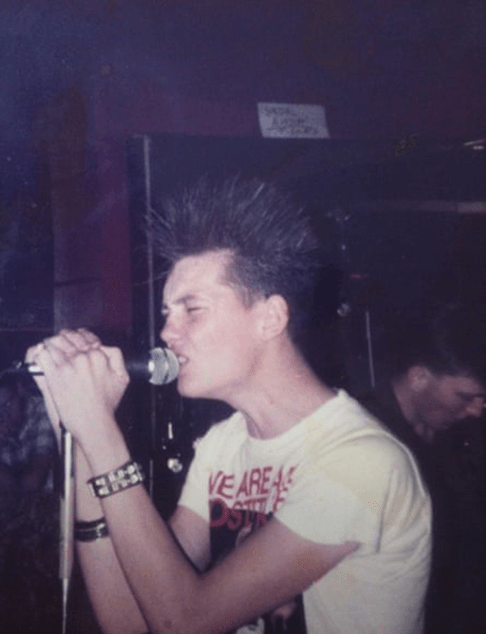

But the soft kiss Tully gives Anna is, in my mind somewhat still necessary to put into a context of touch between male bodies, wherein, ‘Tully gripped my hand for a second …’.[15]. But I do not know what to make of this as a queer reader. All I would urge that it is not as straightforward a prose elegy as it seems. Because boys who are living the struggle to become men is about living the ambivalent paradoxes of how masculinity is constructed. The final passage I quote is perfectly illustrated by a picture of Keith Martin wearing the t-shirt mentioned in it. But it is also about how a ‘taste for ambivalence’ must lie within any judgement about categories like what men are. So I leave it for a reader to reread.

He was wearing his “We are All Prostitutes’ T-shirt …. Now the other men in the bar were heroic to Tully and me: they were sacked workers, guys who were struggling in a town that had been designated an unemployment black spot. But Tully had unearthed an irony: they were victims, these veterans of the fight against Thatcher, but he was the first person I knew, and perhaps the only one, who saw they could also be victimisers. Tully understood that difficult things did not cancel out other difficult things. he had a taste of ambivalence, and I’d never met anybody before who possessed that so naturally.[16]

So can we read the male relationships queerly. Well: ‘difficult things (do) not cancel out other difficult things’. (We should cultivate) ‘a taste of ambivalence’. And ambivalence is very queer.

O’Hagan is at his best here (he really is) and this novel helps with reading his early work in many rich ways.

Steve

[2] ibid: 4

[3] ibid@8

[4][4] ibid: 4, 101

[5] ibid: 101

[6] ibid: 102

[7] ibid: 4

[8] ibid: 6

[9] ibid: 129

[10] ibid: 130

[11] ibid: 132

[12] As in ibid: 246f.

[13] ibid: 232

[14] ibid: 185

[15] ibid: 184

[16] ibid: 12f.