‘What people see shapes how they treat you, Ma said again and again’.[1] ‘Sister, one is named, and the other, Brother. Sam swings in, then out, of the trading post’.[2]

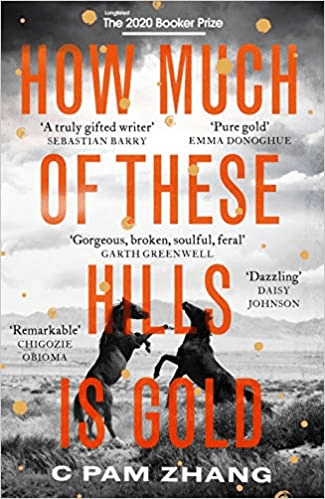

Booker 2020 Longlist Selection no. 4: C. Pam Zhang (2020) How Much of These Hills Is Gold London, Virago.

It is difficult to write about How Much of These Hills Is Gold and I’m doing it just to scratch on a piece of paper a homage to a book bigger than any one person’s take on it. Moreover no-one could be more disappointed than I at the failure to really articulate an argument about the book here. For that reason too, I’d urge anyone who dares, and is kind enough, to read it, to see it as homage first and foremost to a writer.

The setting and imagery of How Much of These Hills Is Gold are much the same thing. That is as usual a circumstance in any satisfying large mythical history in which origins are explored, subverted and reinvented: even potboilers like Gone With The Wind. In this new fascinating novel, the materials are mineral gold, hills in their appearance and stranger geological reality and history, tigers, all-consuming elements like fire, water, muddy earth and underneath all of this the taste of blood and salt.

These features we can, inside the novel, consume and introject – just as Ma stuffs mud into her mouth. But they also are our excretions, not least where we psychologically project our individual and group identities back into them. It is all so rich, whether we use that word to look at an economic status (where vast piles of gold abound and circulate) or as a metaphor for a complex nuanced mix of our organic, socially symbolised (in clothes or other things) and imaginary or imaginative lives like those of the many types of tiger in the book. All of these things interact and this is no philosophical venture as is Love and Other Thought Experiments, a competitor on the Booker longlist. Let’s take a typical instance from some of those interactions in the use of linguistic figures that become realities and then slipped back out into the imagined. Ba has brought back a nugget of gold from a visit to the old sea-bed of the now dry hills.

“You’ve been prospecting,” Ma says. …. “Kan, kan, this is what I think of prospecting.”

Ma tips the pebble to her mouth and swallows. Like bone and like mud, another piece of land slips down into her. Sam wails. Ba looks shaken. But then he grins.

“Mei went ti,” Ba says. “Plenty where that came from.”

“I ate it,” Ma says, slumping. Poor posture pushes her belly out, rounded now as the hills are rounded.

“He ate it,” Ba says, and this time Ma lets him touch her. “Why, he’ll be rich. Come here, Sam. Show your ma!”

Sam comes forward with a dirty old pouch. …..[3]

This feels to me as if it is explicating the very origin of how perception, metaphor and language interact to influence each other. In part this is because of the dialect of Chinese, not explained as such to the reader till much later, that the characters use. That very usage will turn out to have a complex history of acquisition or recapture, especially for Ba, but here it is the children, Sam and Lucy, and the reader for whom its meanings and application are as yet far from clear. We confront language as shapes in type and of unsure soundings, as we do with languages unknown to us. But then a place becomes a simile through the visual potential of a word like ‘rounded’, out of which the hill of Ma’s pregnant belly comes into focus. Gendered pronouns come into play. ‘He’ is the prospective child, a child who will be still-born, but which by all kinds of slippage also becomes Sam. Ingestion turns interiors into a correspondence of exteriors: what is outside slips inside. The signifying system appears in flux, just as the intuited emotional interactions between characters is in flux – ever hardening and softening into different attitudes and tolerance of each other’s relative proximity.

Even more complex examples occur, such as a fire-tiger amalgam of the elemental organic in a crucial moment, that should not be spoiled for a reader: ‘Lucy, I swear those hills birthed a tiger’.[4] Gold, of course, is crucial as a colour and appearance, as a material mineral and deposit of geological events, even the birth and death of seas and lakes. It is at the centre of discourses in the novel about what we mean by value, as in the history of capitalism it always was, under the guise of the economists’ gold standard. And gold, far from being in itself the rare commodity against which value is measured, might also be a mere appearance of the life and death of labour that goes into its ‘production’: as the interior of life-yielding land is scoured from deep within into the outer world and becomes, together with excreted by-products, its pollutant.

See here, for instance how the ‘cost’ of meat derives from gold in the usual rich exchange of figurative language. Lucy contemplates the sacrifices that enabled the purchase of meat on which to live:

Lucy will blame the meat, and even later she’ll blame the cost of that meat, and the long desperate days worked to pay that cost, and the men who set that price, and the men who built the mines that paid so little, and the men that emptied the earth and choked the streams and made the days so dry, and the claiming of the land by some that leaves others clutching only dusty air – but think too long and Lucy grows dizzy, as if sun-stunned on the open hills. Where does it end, that hard golden land that haunts her.[5]

The same exchanges – at the end of the novel in a repeated chant of grass and gold, with the associated chime that ‘all flesh is grass’ moves through the novel, especially in the set pieces which describe not only the geographical but the moral-historical setting of the birth of the Californian ‘Gold Rush’, a phenomenon the novel insists really started between 1841 to 1842 and forced immigration of labour from the East (and not 1848 to 1849 as white history would have it). It is as radiant in the novel as it is also, under its shine, dry, dead, the sign of scarcity itself: ‘the yellow grass of this land, its coin-bright gleam in the sun, promised even brighter rewards’. Instead they get: ‘the land’s dry thirst’, which ‘drank their sweat and strength’.[6]

All the time, this novel questions origins. The origin of the Gold Rush in history is only one theme. The most poignant form being the questioning of immigrants, and onwards in their generations the sons and daughters, whatever the longevity of their birth in a land they have adopted, but which has not adopted them, of, ‘where do you come from.’ Given a specific answer detailing local movement in the USA, entitled and unconscious racism, in the form say of Teacher Leigh’s promotion of ‘civilization’, says: ‘“Where are you really from, child? I’ve written at length about this territory, and never encountered your like”’.[7]

This question still haunts American-born people of colour or other culturally signifying difference. It is the question that excludes rather than includes and it is difficult to answer. The difference in the South East Asian ‘origin’ of Ba and Ma, signified in language amongst other things, is only gradually revealed, and then mistily and under repression, for all kinds of reasons psychological, economic, social-historical, and cultural through a novel where communication must too often ‘pry silence open’ with its voice.[8] The whole story often hinges on the unspoken and the buried (Ba for instance must be buried – indeed with flesh liquified in salt (another ancient determinant of value)[9] – before he speaks more fully in part 3 of the novel.[10] Lies and secrets and language currently hard to comprehend as well as silence bury truth: ‘”Na zhang da lei. Old enough to know what’s a lie, and what’s better left unsaid. remember I taught you about burying? Well, sometimes truth needs burying too”’.[11] The children in the novel hear the word ‘chink’ in the novel for the first time well into their development and the novel. What it originates in human beings is the consciousness of racism.

I am leaving out a long of what further could be said about issues of race, immigration, oppression and nationality though to concentrate on how the novel works on the currently vexed issue of sex and gender. It puzzles me that certain strands of current feminism have tied themselves so much and foe so long to a naïve brand of biological fundamentalism on this issue. It may puzzle C Pam Zhang too, although she has publicly committed the novel to a group of ‘us’ made up of ‘Asian womxn and non-binary people’.[12] There is here again, as in the best non-fundamentalist and scientific biology which I equate with Anne Fausto-Sterling, a refusal of easy myths of the origin of sexual binaries and heteronormativity, which imagine moments of indifference between sex/gender (the basic interactive category of sexual development in Fausto-Sterling) personae and identity role, just as there is such a primal identity for the early foetus before the operation and articulation of genetic coding. In this moment, for instance, in the reunion of Lucy and Sam:

Her hair’s been shorn …. Not a man’s cut, not a woman’s. Not even a girl’s. … Up till the age of five, this was the cut Lucy and Sam wore before they wore a girl’s braids.

She smiles. Her reflection smiles back. Her face is reshaped, her chin looking stronger. This is the cut of a child, androgynous still, who can grow up to be anything. …[13] My italics

I would argue that kind of indifference to sex/gender, even when confined to appearance like a haircut and its effect on the perception of facial structure, is also a kind of claim for persons to develop a constant ability to exchange roles. Both of my chosen title quotations address this. There is an important connection between what we feel we are, the appearances we project and the treatment we receive. That Lucy and Sam ride horses they name Sister and Brother tells us not only of the choice of sex/gender personae but the right of the two persons to choose them. We are not told which sibling rides which horse just as when Lucy looks comparatively at their hands as they eat and those of Indian travelers (sic.), there is really no difference in them. The sense that we use difference to other and exclude that defines the real world is entirely absent. Difference is the condition of our sameness and readiness to treat each other as equals: ‘Same and yet changed. … What people see shapes how they treat you’.[14] And these lessons play around with the way the reader is variously allowed to see how gender originates for both siblings, including the roles of sister and brother and/ or sisters which are never easy to allocate and often times motivated by some other reason in the book.

For instance, Sam’s choice of male garb add convenient value to her for the family as a labourer: ‘Sam’s wish comes true. The red dress is laid away, a shirt and pants cut down to size. Boys get paid more, Ba says, and Ma doesn’t argue …’.[15] That such inequalities feed sex/gender choices is also underlined by the story of the still-born biological son who is expected for a long time in the novel, and which in the slip of speech is the only inheritor of the family’s labour on and possession of land:

‘…“I mean to buy a parcel of land out in these hills. … We’ll all have the space to hunt and breathe. That’s the kind of place I aim for him to grow up in. Imagine that, girls. That’s proper power”’.[16]

The writer could not have emphasised the contradiction more clearly. When girls are asked to imagine ‘real power’, it is male, and is not a space for girls, at least not primarily, to grow up in. That men posses power, wealth, land and rights is a motive to choose masculinity where such a choice offered to you, as is Sam’s wish, but it’s not a solution and Sam’s achieved masculine power by the end of the book is one that knows the limitations of masculine entitlement book sexually and economically. The phallus is never much more than a carrot in this book, like the one the young Sam uses as a substitute thereof: ‘A hard, knarled protrusion’.[17] But it was a choice of Sam’s despite the complex longing for a boy to inherit in Ba. Even Lucy saw that choice: ‘What Ma called sullenness. What Ba called boy. ….with a mixture of admiration and envy’. Sam avoids socialisation as the girl Samantha by choosing to be lost from the social acceptance, which Lucy chooses together with conventional femininity:

becoming precisely who Sam wanted to be. … After five years missing, five years lost, five years without place or person to box Sam in, …. [18]

It’s in those same five years that Lucy consolidates her own choices that lead her desires to ape those of a society that will and must reject persons of her race and class. That rejection will be enacted by Anna, the rich daughter of a successful prospector and mine-owner. Whilst Sam yearns for the great outdoors, a house owned by a teacher of a higher class, unlike that den of Ma and Ba, is what animates Lucy’s desire: ‘a house so orderly it made Lucy’s heart beat fast’.[19] Femininity buries ‘more and more of herself’ in Sweetwater.[20] And that comes with seeing the way in which the association of men with what is hard and unyielding may be necessary even for the excluded woman: She sees that when she learns of why Sam needs a, ‘coiled violence in that voice, like a pulled-back fist.’ Sam can change to look like, and in doing so be, enough to threaten Anna with ruin, the, ‘hardened man unknown to her’.[21] But these sex/gender reversals are only different to those that occur in the gender-normative societies which hide them under a lie. It is only when Ba dies that Lucy and we learn that Ma not Ba only plays at the feminine, a thing in fact that she delegates to Ba:

Your ma spoke prettier than me by the end. Looked prettier too. People thought me hard her soft. We made a good team. … But believe me, Lucy girl, when I say your ma was even more fixed on making a fortune’.[22]

The gender reversals here play games with who is hard and who is soft. I cannot though pretend to know how the complexities around them are best expressed in this novel. It is too good a novel to be absorbed in one and perhaps in many readings. it covers the myth of origins of civilizations (that which is not the tiger), geography, history, sex/gender and racial differentiations but even my few thought about sex/ gender feel to me inadequate as yet and perhaps will remain so. This is the debut novel I would think of a very major novelist.

Steve

[1] Pam Zhang (2020: 108)

[3] ibid: 108

[4] ibid: 182

[5] ibid: 96

[6] ibid: 10

[7] ibid: 92

[8] ibid: 90

[9] A favourite sentence of mine is ibid: 34. ‘She thinks of the plums Ma pickled in salt, the way they took a form more potent than their origins.’ One could write for ever on this sentence.

[10] ibid: 161ff.

[11] ibid: 104f.

[12] See Tweet https://twitter.com/cpamzhang/status/1287907603838722048

[13] Zhang op.cit.: 237

[14] ibid: 243 (note re-quotation from ibid: 108)

[15] ibid: 100

[16] ibid: 110

[17] ibid: 13

[18] ibid: 216

[19] ibid: 101

[20] ibid: 233

[21] ibid: 231f.

[22] ibid: 172

One thought on “‘What people see shapes how they treat you, Ma said again and again’. Booker 2020 Longlist Selection no. 4: C. Pam Zhang (2020) ‘How Much of These Hills Is Gold’ London, Virago.”