Do see this great film! Reflecting on Jane Austen’s Emma after seeing a recent magnificent screen version of Jane Austen’s novel: A film directed by Autumn de Wilde with screenplay by Eleanor Catton.

I studied Jane Austen’s novel, published in 1815/16, Emma for A level in the 1960s. It opened my eyes to the link between the highly structured tonal contrasts of the prose and the intensity of the ethical decision making that animated those effects. Decisions about what to do, say, think and feel are predicated within a sentence in a way that would change the potentialities of the later novel.

Emma Woodhouse, handsome, clever, and rich, with a comfortable home and happy disposition, seemed to unite some of the best blessings of existence; and had lived nearly twenty-one years in the world with very little to distress or vex her.[1]

The word ‘seemed’ in this opening sentence has a moral weight that first weighs against some unstated standard of truth the question about what in truth constitutes the ‘best blessings of existence’. Second, it suggests the probability of some artificial and unworthy over-contentment in the moral developmental of a young woman, approaching the symbolic age of 21, with a life lived without ‘very little to distress or vex’ its subject, Such a life is one Plato’s Socrates called ‘unexamined life … not worth living’ and, as with Plato, the sentence questions the truth and reality of such a life.

In our school our English teacher, a late Downing College, Cambridge scholar had been taught by F.R. Leavis. For me, for a period well into my English degree in the 1970s, Austen was as Leavis named her, the first of the great novelists of The Great Tradition Leavis identified because she made art animate nuanced moral decision-making. Leavis summarises this quite aptly in his tortured prose.

But her interest in ‘composition’ is not something to be put over against her interest in life; nor does she offer an ‘aesthetic’ value that is separable from moral significance. The principle of organization, and the principle of development, in her work is an intense moral interest of her own in life that is in the first place a preoccupation with certain problems that life compels on her as personal ones. She is intelligent and serious enough to be able to impersonate her moral tensions as she strives, in her art, to become more fully conscious of them, and to learn what, in the interests of life, she ought to do with them. Without her intense moral preoccupation she wouldn’t have been a great novelist.[2]

A weighty subject indeed was the Emma I inherited from the teachings of this paradigm of tradition and its insistence that every decision we make – in reading as in life – was a judgment on one’s moral sensibility as well as efficacy. One way in which this sense of weight expressed itself was in an extraordinarily strong tendency to despise dramatics adaptations of her novels, and particularly of Emma. The lack was equivalent to seeing a ‘life unexamined’, that of Emma herself through the first half of the novel, as a merely decorative or humorous thing. This adaptation is a quite different thing. It uses the script and dialogue of the novel at crucial times but it reimagines many of its episodes in the manner of someone who understands not only the tradition of the novel but the import of contextualising its scenes and episodes with a difference for modern viewers and in a language that is dramatic and visually cinematic.

The changes that tell most and feed a contemporary moral sense into a view of history include the much larger part played in the telling of the story by the effect on the business of modern life of the presence and function of non-speaking servants and indeed of occupations, like medicine, that served the ‘handsome, clever, and rich’. It may seem strange to see Mr Knightly naked so early in the film, setting him up as an object of sexual interest in a way that it’s difficult to find easily in the original text. but that nude scene is actually one that stresses the way in which the everyday lives of the handsome, clever and rich are lived with a kind of dependence on one’s own position and wealth and the purchase in part of one’s own everyday helplessness without money.

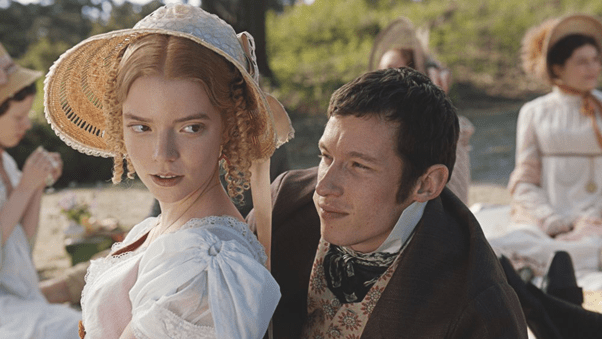

Strangely enough that gives even greater focus to the moral centre of the novel and the major episode of the moral education of Emma – the picnic at Box Hill. For here, her poor judgement of men and their power, based on exceedingly superficial appreciation of the role of patriarchal inheritance and the very real dependence of women on men, makes her insult Miss Bates. as Knightley says, she is a woman who once commanded social respect but has lost all claim to it by not being marriageable and, if she lives, ‘must sink further’. And it is clear she does this by misunderstanding how she should act with powerful men like Frank Churchill, she succeeds in humiliating thereby not only miss Bates but at least two other vulnerable women in the novel, Jane Fairfax and Harriet Smith. The following still from the fil exemplifies these moral issues almost without words.

Here Emma turns her back on women and her responsibility to them and herself in making a supposed secret, but very publicly secret, understanding (that turns out to be such a gross misunderstanding) with Churchill. Much is being done with the directed vision of eyes here, even of the pupils of eyes and the semi-closure of eyelids that is morally precise – as beautiful in its own media as Austen’s moral prose.

As a result, an adaptation that takes obvious liberties with the text, is nearer to what I see as its ethical and socially critical heart of the novel than I ever imagined to be possible.

Do see this great film!

Steve

| Short Cast list (excerpt from: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt9214832/fullcredits?ref_=tt_cl_sm#cast ) |

[1] Jane Austen’s Emma in the Gutenberg Project version. Available at: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/158/158-h/158-h.htm#link2HCH0001

[2] Leavis, F.R (1948) The Great Tradition. Available online: https://archive.org/stream/greattradition031120mbp/greattradition031120mbp_djvu.txt