‘The taxi took the boy through the busy heart of Glasgow, … . They passed the Victorian train station, and he saw lost-looking boys his own age standing in bubble-shaped anoraks and tight denims, loitering around the arcades and amusements that clustered nearby’.[1]

Booker 2020 Longlist Selection no. 3: Douglas Stuart (2020) Shuggie Bain London, Picador.

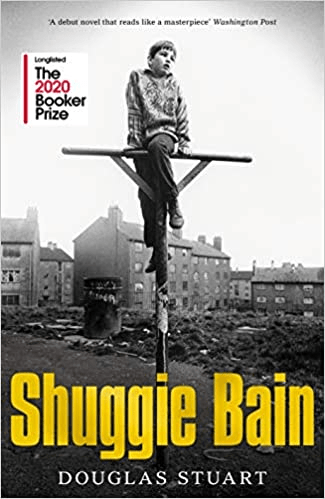

Glasgow still has a busy heart and it is probable that that heart still contains numerous working-class ‘lost-looking boys’ like Shuggie (Hugh). Like Shuggie because at this moment he, like them, he has been papped, a term used by Agnes Bain and her sons Shuggie and Leek (Alexander) to describe being thrown out of his home by a mother.[2] A heart full of papped, and otherwise lost, boys is what the lovely cover-image to this book (by Jez Coulson from a photograph by Martyn Pickersgill) points towards. In that image, a young boy’s torso forms the upper part of a crucifixion icon which bears him as its witness and victim with the gold ‘i’ of the word Shuggie making the base of the crucifix. The image reflects the scarred urban landscape behind the boy, the wasteland of a council scheme that has seen better days. This is a novel that covers a catalogue of areas run into poverty in the 1970s and through the period 1981 and 1992 covered by the novel’s story.

For some commentators, this very much makes this novel about the fate of the ‘inner cities’ of the UK under Thatcherism and its blindness to the effects of mass male unemployment from the traditional heavy industries that set up these cities. It covers areas like Sighthill and its huge area of high-rise tenement flats, out-of-town mining areas (called Pithead here and their sprawling schemes – would be called council estates in England – of standard housing) and the East End.

In March 2020, Eliza Gearty in the Jacobin online magazine, stressed what she saw as a possibly over-exaggerated picture of the degradation of Scottish working-class communities and a stress on the inversion of female and male roles that came with deindustrialisation and Thatcherism.[3] As Gearty says:

… it’s not Stuart’s responsibility to provide an all-encompassing historical overview of the Scottish working class. He’s a fiction writer — and his novel is saved from the “misery-lit” trap it could’ve fallen into by the utter beauty of its writing and the sheer authenticity of its world. Stuart himself grew up in public housing in Glasgow, and he approaches the many social problems his characters encounter with delicacy and compassion.[4]

Although this is undoubtable, it may absolve novelists from social responsibility too easily. There are instances of novels that tread similar social ground and focus largely on working-class boys or youth, akin to Shuggie and Leek, but they resolve the issues in representing the working class very differently. James Kelman’s Kieron Smith, Boy (a masterpiece) and Graeme Robertson’s The Young Team (which is near the same category) both insist that on getting nearer to actually working-class experience by their choice of narrative perspective and the language which expresses that perspective. In Kelman’s view doing this was the solution of a problem that novels set artists – to portray their subject matter without distorting its meanings through the bourgeois conventions of the medium itself. Stuart is doing something quite different, as shown by the relentlessly consistent use of third-person authorial narration from another place that the consciousness of his characters, which the other writers mentioned in this paragraph in large avoid.

Even the use of dialect words is extremely sparse, though necessary to indicate the milieu at the linguistic level while refusing to be absorbed in it. The novel end with a fine example: ‘He nodded, all gallus and spun, just the once, on his polished heels’.[5] The term ‘gallus’ with its roguish sense in Scots, balances against the overall effect of the adjective, ‘polished’, to describe Shuggie’s demeanour and his possible future in a new class and the polish of the syntax of the short sentence itself finessed by beautifully tonalised subordinate clauses.

Other uses show similar effects that display the effect of the native languages of the characters without endorsing it as the voice of the polished narration. Sometimes it is a beautiful metaphor that distances us from both the culture and the consciousness of the character, as in this characterisation of big Shug, in which the word ‘shallow’ does a lot of complex signifying work: ‘vain in the way only Protestants were allowed to be, conspicuous with his shallow wealth, …’.[6] The character is pinned, like a beautiful moth, in its author’s showcase by such small details of apparent ‘style’. See this effect more clearly across an incident in which see the ‘working girls’ are watched by Shug, on taxi-duty (also eyeing them up simultaneously), and us – voyeurs both. Language like ‘short stoat’ and ‘the dreich’ on page 39 just dips the characters, not the prose effect on the reader which remains socially distant, in its social milieu.

And, despite some commentator’s view that this novel is kinder to women than men and is dominated by the trapped dignity of Agnes Bain’s, the same is done so often to her. Thus the reader is asked to see the ‘dining room of the golf club’ that Eugene takes Agnes to, and its menu, in two ways. Once as a sophisticated voyeur to whom this setting and menu is, at the very least, ordinary, and once as something far beyond the social distaste implied by it being ‘common’ (a word to which we will return again).

The dining room of the club was simple, but to Agnes it was the height of class … / …/ She didn’t know what all the things were, but to suddenly see it all laid before her, and know she could have the pick of it made her feel light-headed. It was like a Freeman’s catalogue, only better. She ordered what she understood, and then sat there worrying about the cost.[7]

The balance of the first sentence here is poised on a reader knowingly superior or at least equal to the milieu and another perspective (Agnes’) that sees it as ‘class’ from the base of a working-class origin. It fixes Agnes on her pin. Of course, we feel for Agnes but our feeling is not trained to be that of an equal to her at all but to look from above. The sentence about the ‘Freeman’s catalogue’ types her immediately.

Only having discerned this will we get nearer to the novel’s basis in a social vision. Because this is a novel about how class shapes us and how it frees us, if it ever does from its shaping. Shuggie is important to the novel, its focus, because he learns from Agnes an ambivalent attitude to her class, and that class’s men, that brands it as limiting but is forever its victim, even though all her children make something much more in a position in at least a marginally different stratum that that of the characters stuck in it. Agnes is the incarnation of how ‘class’ appears in the eyes of a working-class woman brought up in the age of a mass market for strong and classy, if fundamentally shallow, images of women. In my view that is the role played by the constant comparisons of Agnes to Liz Taylor.

A primal scene is that in which Agnes sees in a mirror, ‘A facsimile of Elizabeth Taylor’ …, only now it was Liz, the vain and haughty version from the paparazzi …’.[8] From Agnes, and from his complex relation to those shifty signifiers to class to the working class of the 1980s (I remember them well), his mother’s ‘Capodimonte knock-offs’ he learns a fragile sense of value.[9]

The episode in which Shuggie is nearly sucked into the black bog of a coal-mine’s feels to me an allegory of this process rather in the way Dickens sees class descent as being sucked into the mire of a lock in Our Mutual Friend, rather than a realistic depiction of life. The source of Shuggie’s elevation, and Leek’s let it be known, is this mother who mistakes her own class, without any of the bitterness of Paul Morel’s similar mother otherwise in Lawrence’s Sons and Lovers. That is her tragedy. It may be her children’s making. He uses the word ‘common’ as Glasgow boys do not.[10] His mother defines her specialness by differentiating herself by this word and attitude to life. From she Shuggie got it and he will not let it go.

Shuggie also learns a more proper pronunciation of words and as a result a voice, syntax and verbal repertory that divides him from other working-class children.[11] He summarises the two beings that the reader is invited to see in his mother with a binary precision that is very highly comic in this highly social poised and knowing little boy who can look down on Glasgow women who have become nurses, like Sister Meechan, who thinks Agnes ‘a working girl’, in short a prostitute. To Sister Meechan, Shuggie replies, ‘quite proudly, “my mother has never worked a day in her life. She’s far too good-looking for that”’.[12] Walking past the mean-minded working class women on the Pithead scheme streets, both mother and son play at having ‘class’.

She strutted out a confident rhythmic clip and turned her head and said to the boy, “What would you like for your dinner tonight?”

Shuggie looked up at his mother and did as he was taught. “Roast chicken, please. I’m a bit tired of sirloin every night”’.[13]

Shuggies’s difference to others extends to his gait, gestures and stance which recall the dancing he does with his mother.[14] Again, Shuggie is our focus because he, like his mother, will not act ‘normal’, despite the many men that try to shape his behaviour, such as the luckless Jamesy McAvennie and Eugene. He has a ‘trampled grass circle’ in Pithead, trampled because it is here that he, under brother Leek’s instructions, ‘practiced being a normal boy’, only to end the paragraph spending, ‘the day feeling house-proud, … as dutifully as any mourning widow’.[15] Shuggie’s differentiation in his class is from the boys in particular but there’s no accounting for the delight that is ‘Little Mouse’ McAvvenie. And that differentiation is tied, quite uncomfortably I think, to the many ways in which Shuggie is not only feminised by others, presumably from aspects of his body regulation, but characterised as a ‘poof’. Teachers even tolerate such name-calling, as indeed I know they did in the 1980s.[16]

I say uncomfortably (for me only perhaps) because so much of the novel is, as I have noted Gearty to say, about gender-roles and their inversion across social domains. The archetypal male in Shuggie Bain is the taxi-driver, a casual role, often undefended by a union and cut-off from other social bonds. King of these men is Shug Bain, Shuggie’s biological father, but other taxi-drivers mark his and his mother’s life, like the ‘red-hearted ox’, Eugene, for instance who courts Agnes.[17] But taxis also transport Shuggie on his own across Glasgow when crisis hits his relationship to his mother. In the first of those occasions, the man finds a way to push, ‘his warm fat fingers down the back of Shuggie’s underpants’, and ejaculates (though Shuggie does not easily interpret these signs in the man’s breathing) whilst ‘searching the boy with his fingers’.[18]

What are we to make of this man? He is almost replicated in the opening chapter from which the novel moves back in time, where Shuggie, like his mother, searches his reflection in a shared bathroom mirror in his lodgings. Not for Liz Taylor as Agnes searches and finds, let it be said, but for, ‘something masculine to admire in himself: the black curls, the milky skin, the high bones in his cheeks’. Lower down the same page, we learn that he is being observed through the keyhole by Mr Darling, who has a ‘considered, half-closed way to himself’. When Darling further seeks to ingratiate himself, as Jinty does her mother, with a supply of Special Brew, Shuggie feels, ‘the burn of Mr Darling’s finger against the side of his leg’. [19]

The largely unseen presence of Father Barry, Shuggie’s Catholic mentor raises other issues. The only possible healthy attraction to Shuggie from another male his own age comes from a ‘ginger lad with the pierced ears’, whose ‘gammy eye’ may have meant he was not looking at Shuggie at all, at the very end of the novel. Otherwise, Shuggie is continually called a ‘wee poof’, or ‘poofy wee boy’.

Shuggie brings out in some men the need to discipline him, in boys the need to fight and name-call. He is called a boy who ‘likes willies and bums’ and whose mother has told them to avoid (so Francis McAvennie says, but with a mother like Colleen it’s possible) lest, ‘ye try and put yer finger up my arse’.[20] The boy ‘Bonny Johnny’ who defines a ‘wee poof’ for him as, ‘a boy who does dirty things with other boys,’ makes Shuggie’s frail body bleed by an act of treachery, but ends their meeting with the request to Shuggie, ‘”Now you rub me”’.[21] Even Francis McAvennie later seeks a sexual liaison of dubious sincerity with Shuggie, even if it be only a kiss through a letterbox.

We know that Shuggie does have positive desire for boys, if not the abuse of boys and grown men, only when he chews his friend, Keir’s, wad of gum. Keir, though, is not in this seeking a mutual relationship:

“Don’t be a fucking poof. Here!” Keir thrust the gum at him. Reluctantly, Shuggie took the wad and put it in his mouth. … He found he didn’t mind; he rolled it slowly around his mouth and savoured it. He used his tongue to push the last of Keir’s spit into the dry pocket above his teeth, behind his lips, like it might last longest there.

What makes Agnes so important in the novel in this respect is the sense in which she appears to sometimes want but will never be ‘normal’, whatever the available instruction. sometimes such instruction is not necessarily malignant, as in The Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) scenes but It assumes severe discipline is required. Eugene feels that AA is wrong to ask people not to abstain from drink entirely because it is not, ‘what normal people do’.[22] But both Shuggie and Agnes learn together that to be try and act and be normal is not always a positive step, nor possible. Anything else is to turn your life into a ‘lie’.

He had lied to Agnes as she had lied to him about stopping the drink. She would never be able to get sober, and he, sat in the cold with a lovely girl, knew he would never quite feel like a normal boy.[23]

Even Leek who knows how to act like a man, in that he teaches Shuggie to teaching to walk like a man:

Leek made a great pantomime of walking like Shuggie. His feet were pointed neatly outwards, his hips dipped and rolled, and the arms swung by his side there was no solid bone in them. “Don’t cross your legs when you walk. Try and make room for your cock2’.[24]

My suspicion then is that this is not the novel that exposes Thatcherism as its primary target but more importantly, at least in its own terms, a full-frontal attack on heteronormativity, a queer novel, that shows the role of heteronormativity particularly in working-class communities in decay. In its ‘busy heart’, lost-looking boys in tight jeans find a society that is predatory not only economically but sexually. It should not be lost on us, that at the end of the novel, Shuggie attempts to get out a tight corner by offering to sell his body sexually to a taxi-driver, who, this time, is not interested in such an exchange, as his taxi fare. It is a plea to save boys from such lies and some of the male predators on them, who in the light of day would not seek satisfaction in a ‘half closed’ way as does Mr Darling. Or at least it is that in part. It is also a kind of queer bildungsroman with great fun and danger in it.

Steve

[2] I have been unable to find this exact usage in any online Scottish or Scottish slang dictionary, but the meaning is clear from its use by these characters. Ibid: 398 (Agnes “…Get your bag. You’re papped!”), 403 (Leek “… You were papped for being a nagging moan.”). But see these instances: https://www.dsl.ac.uk/results/papped

[3] Gearty, E. (2020) ‘Shuggie Bain, a Window on Postindustrial Glasgow’ in Jacobin Magazine (online) (16th March 2020) Available at: https://www.jacobinmag.com/2020/03/shuggie-bain-glasgow-book-review-thatcher

[4] ibid.

[5] Stuart (2020: 430)

[6] ibid:28

[7] ibid: 297.

[8] ibid: 284

[9] ibid: 307

[10] ibid: 152

[11] ibid: 51

[12] ibid: 177

[13] ibid: 327

[14] ibid: 266f.

[15] ibid: 330

[16] ibid: 378

[18] ibid: 316

[19] ibid: 12

[20] ibid: 260

[21] ibid: 122-124

[22] ibid: 301

[23] ibid: 393

[24] ibid: 152

4 thoughts on “BOOKER WINNER: “lost-looking boys his own age standing in bubble-shaped anoraks and tight denims, loitering” Booker 2020 Longlist Selection no. 3: Douglas Stuart (2020) ‘Shuggie Bain’.”