Queer ethics and re-reading Vikram Seth’s (1986) The Golden Gate: A Novel New York, Random House & London, Faber and Faber.

‘Ed frowns: “ I can still strive for purity / Of heart – “ “… While in its sweet maturity / Your lovely body dries unused? / Ed, if that’s so, you’ll have abused / Your self – and God’s gift – far more truly / …’

(Stanza 8.27)

I think the literary production of the 1980s is often disguised because thence starts its ‘professionalisation’. This includes increasing reliance on writing on courses in universities and the understandable choice of writers in precarious economic situations of beginning to rely on funded posts in those universities teaching creative writing, or worse, academic approaches to literature. Vikram Seth started writing poems at university but not as a learner in ‘English’ but in ‘Economics’. His position was privileged by the wealthy background from which he emerged and the high culture, independent of academic pressure, of his family. That family must have been somewhat like that of the Chatterji family, with its penchant for the production of comic rhyming couplets, in A Suitable Boy.

What it wasn’t was dependent on those professional parameters that were to make modern literary production dependent on distinct institutions that mould literary production to the demands of a notion of the ‘modern’ in the networked worlds of journalism and academia. As Seth says in the ‘Introduction’ to the 1994 edition of his first published poems (published in a ‘slim, stapled, paperbound volume’ in 1980), Mappings:

I was studying Economics, not English, I stood outside the orbit of the latest critical theories, and did not realize that writing in rhyme and metre would make me a sort of literary untouchable.[1]

I’d argue that this poetry also had a more direct line of relationship to the debates outside of the institutions that shaped the discourse of the modern as something distant from the conceptions of what by what were, even then, the guardians of an elitist discourse. When Seth addressed changing sexual identities, he addressed them directly and without the need for an ‘objective correlative’ or the avoidance of rhetoric merely formed into musical measures This was a poetry of literal statement that paid no heed to James, Eliot, Woolf or Joyce. He even dramatized this literary problem in the ‘apology’ (or perhaps apologia) for writing his novel in verse that starts Book 5 of The Golden Gate.[2] See below two poems from Mappings:

These poems do not evade the self nor do they avoid controversial neologisms. They are as direct a reflection as you can get on queer identity (this is more than merely gay identity as the term Dubious already insists). Being ‘Stray or Great’ is as near as you can get to the contemporary definition of queer as an amplification of the refusal of norms. Similarly the experience of Guest is that of how an incident common to queer people of simple attraction gets lost in obfuscation of the meaning of any sexual event as these two men face the morning after of something that, for all intents and purposes to any person outside the space called ‘his room’, may or may not have happened. Even the use of ambiguity, wherein the ‘lie’ about where they ‘lie’ makes sense in two ways of the trust that was broken by their need to appear not to have slept together. To lie ‘coiled’, like a snake, is not to care to preserve the trust of any embrace that might have happened.

If this is poetry that used more than one type of ambiguity, it did so in the interests of conveying the reality of queer lives not the cultivation of an art outside the messy stuff of life that so hooked the pursuit of poetry in other places – increasingly a ‘pursuit’ (think of I.A. Richards and F.R. Leavis) tied to the academe and / or (but not the latter for Leavis) the London metropolitan clique that stemmed from Bloomsbury once upon a time. Nothing like these early Seth poems was common in the poetry published in the mainstream. It wasn’t just unusual because it was highly regular in its form – the sonnet that shapes Guest would become the basic form of The Golden Gate as a novel in verse. It was also directly relevant.

The direct voice of queer experience in Mappings is not so clearly heard in the later poetry nor his novels till the largely but beautifully melancholic An Equal Music. The queer content of A Suitable Boy has to be unearthed from the heterosexual love-object choice which forms its ostensible subject. I’ve already blogged on this. The narrative work that precede it had a central concern with queer experience but, in a way he perfected for A Suitable Boy, subsumed it to the dominant and ideological heteronormativity of its narrative. It appeared but it couldn’t form the story, just as the poem Guest is end-stopped before it becomes a story that anyone out of ‘his room’ might, in more public space, hear.

Likewise in The Golden Gate, which I prefer to see as a poem on queer sexual ethics that is also tied to a narrative based on the exchange of sexual partners between men and women. The only character left without a story without progression to a knowable end is that character upon which the discussion of the ethics and ontology of love in sexual relationships depends, the old-fashioned High Catholic, Ed. Ed’s moral guidelines come from John Chrysostom, a Neo-Platonic Father of the Early Church. His words to Phil are inappropriate in their tone. The ethical imagery, such as the charioteer allegory (used also by Mary Renault in her 1953 novel about gay men in 1940s London), are lifted from Plato’s Phaedrus and feel sadomasochistic when imagined as speech rather than as thought about human perfectibility. It’s hard not to interject into one’s reading, Phil’s, “Fuck Chrysostom!”, before he does.

8.33

As someone skilled in charioteering

By rein and will and effort must

Control his horses’ frantic rearing.

The body’s turbulence and lust

Must yield to reason’s interventions.

Chrysostom, following Plato, mentions –“

“Fuck Chrysostom. Fuck all the fools

Who play the game by others’ rules ….

….”

This works because no reader blames Phil for cutting off Ed’s diatribe. The verse itself dramatizes less embodied self-control, in fact bodily repression, than that praised by the Greeks. The mouthing of the conjunctions between monosyllabic abstracts slows the line: ‘By rein and will and effort must’. In doing so the reader feels the restrain of the ‘must’ command that ends the line. This is not the grace of embodied integrity that characterises, in the Ancient Greek term used by Plato, σωφροσύνη, which ought to be something different than personal or spiritual pride.

Rather control is seen as violence done to the dynamic and organic body – even in the very physical mouthing by its reader of the verse. The debate between Ed and Phil soon turns into a physical fight in which ideas of the body are not debated but championed by violence, as the wild horses and these lovely bodies are ‘curbed’.[3] The picture of this as the restraint that accompanies the divide between lovers as their cognition is divorced from body and they fail to know each other reminds me of Meredith’s Modern Love:[4]

8.36

No more to say. They change. Unsleeping

On the same bed they lie apart

(What terrifying miles), each keeping,

Unshared, his bitterness of heart,

The longing each feels for the other,

Their unburnt love. ….

The source of that bitterness is never strangely only based on what each of them feel it is. Ed insists it is because of his own personal need for religious purity yet he feels also jealous and shut out by Phil’s history of sexual communion with women. For Phil, bodies of any gender are sweet and their non-use is actually abuse of that for which bodies are for, as suggested by the debate I’ve already cited in the title of this piece.

8.27

….

Ed frowns: “ I can still strive for purity

Of heart – “ “… While in its sweet maturity

Your lovely body dries unused?

Ed, if that’s so, you’ll have abuse

Your self – and God’s gift – far more truly

…”

However, at one point early on in the courtship between the men, he seems to realise that the real problem for him is the same one as for other exclusively gay men, who have encountered ‘falling’ for a bisexual man:

5.10

…

As a strict rule he’s tried to steer

Away from men of Phil’s persuasion.

From common funds of lore he’s learned:

“Fall for a bi, and you’ll get burned.”

My italics

I find that ‘common funds of lore’ really interesting. It is the only representation of the guiding voice of a community of exclusively gay men, whose relationships have faltered on the necessity of ambivalence of desire implied, if not demanded, by the active and continuing bisexuality of one partner. Moreover, if the ascetic Ed is, within the duration of the novel’s story, not destined for an exclusive human relationship, he still maintains his independence of parental needs and wishes and presumably this source of common lore to guide him. This is not to say that Ed is insincere about his Catholicism and the ascetism of his sexual morality but that there is more to him than that. His silent exclusion from end-stopped narrative after the breakup of his love affair with Phil leaves him with just the odd individuality that he shares with his soul mate, the iguana, Scharzenwegger: ‘I may / Find someone who can point the way / Or wait, (…/ …) I’ll decide … next year.” …’[5].

The truth is perhaps that Phil is not what the rather immature young and excessively good-looking Ed requires in a partner, at least not yet. I’d say that was even predicated on the love he feels for Phil that springs from a kind of fascination, which is worth examining in detail. So let’s recall it as already shown on a figure from above which I’ll recopy here.

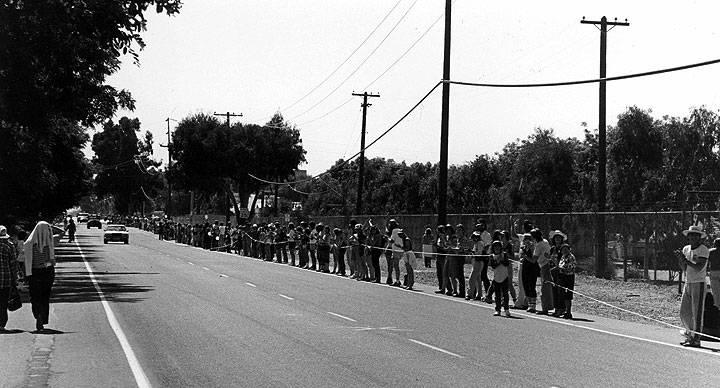

Of course, Seth does not provide the El Greco painting as an illustration as I do here, but the painting contains a lot of meaning for me and I will use this to read the poem. Seth (and Ed) would have seen the painting in the Boston Museum of Fine Art. The context is important since here as later the purpose of a partner is ‘someone who can point the way’ for this man, younger than his years. The main attraction of Phil to Ed is his words. At this point Phil is discoursing in a party on his ideals of political action, relating to the environment and the threat posed by nuclear, and particular neutron, bombs which attack life but not capital, or its architectural infrastructure: it ‘batters / Live cells and yet – this is what matters -/ Leaves buildings and machines intact -/ ….’.[6]

Phil’s part in the attack is on the ‘Lungless Labs’, which ‘Bay Area readers’, like blogger Pessimisimo, recognise as, ‘a thinly veiled allusion to Livermore National Laboratory, where atomic weapons are designed and where a series of nonviolent blockades took place in the early 1980s’.[7] Phil’s articulated politics lift this novel but Seth concentrates on the effects of words on Ed, in making him the something very different from ‘words’, as the very embodied form a listener: ‘wordless, … / Drinking Phil’s speech’. Wordlessness makes him an entirely ‘image’ and captured therein in the person of Fray Hortensio Félix Paravicino, half body and half religious visual icon.

In examining literature we cannot assume that the use of such references implies knowledge deeper than is evinced in the verbal description of Seth, yet the consciousness of Ed seen as ‘image’ does recall salient facts in the relationship of El Greco, the artist, with his subject, the usually voluble poet of Baroque, or Gongarist (volubility in poets is implied in this categorisation), proportions who was Paravicino. Paravicino wrote a poem dedicated to El Greco (‘the Greek’) which says much about what the transformation of human bodies into visual image might mean in the art of the seventeenth century:

This poem employs the same wit about divine subjects as we find in the religious poems of John Donne in England. However, in the context of the Counter Reformation ideology of Imperial Spain, the contexts in religious thought are much more weighty. To call El Greco ‘divine’ is amplified by further metaphors which speak of the duality of the world and the divine in art. To further type his project as Promethean carries the sense of the sin of Prometheus in stealing the gifts of God – life-giving fire – and gifting it to humanity. Hence Paravicino’s request that El Greco not create ‘false fire’ that might gift life to a painting that God desires to see dead rather than alive at the hand of an artificer of icons, a handler of inert materials like paint and brushes.

Yet Paravicino in his poem falls prey to not knowing which body his 29 year old soul should inhabit – that one he inhabits currently or that in the painting. The blasphemy implicit here is obvious: El Greco is challenging God. However, this is a portrait not just of a man but a man interrupted in silent reading, his finger still stuck in the page of a missal, itself resting on a larger book.

Of course, it is difficult to read the iconography of Baroque Spanish art – even more so to know how well a later reader understands that iconography, but it is certain that the reading of holy text was an important icon in religious art. Paravicino’s ascetic Catholicism was extreme – he advocated for instance the destruction of all art containing female nudes. He was therefore without doubt an iconoclast in his thinking and such thinking pervaded the Counter Reformation revival of religious imagery. Victor Stoichita in 1995 argued that such problems in dealing with ‘images’, which might defy the role of God as the only creator, were overcome in seventeenth century art by the iconography of the painted book.

In brief the body portrayed in image is that of the Holy Book’s reader. He is, at a remove from artistic creation an ‘image’ of the embodied Word of God. ‘The Word made Flesh’ is not an act of a painter but of God’s word itself in the Holy Book of which God remained the author. Stoichita’s argument is long and complex but is used well to illustrate El Greco’s The Vision of St Anthony of Padua (1577-9) and other versions of this story, by Murillo for instance. I don’t intend to rehearse it in this already long periphrasis but do recommend the book.[8]

Now how can this help us with the part of the poem in which Ed appears as the ‘image’ of Paravicino.

The same pale, slender, passionate face,

Strength and intensity and grace.

These lines employ assonance, alliteration and rhyme to emphasis the beauty of Ed’s body and the meaning he potentiates. Again the significant use of conjunctions between abstract words give weight to the line in which they appear. So much so that I can’t see other than a deliberate employment of ‘face’ and ‘grace’ (with its Catholic associations intact) in the poem to make material the ‘religious feeling’ that, for a moment Ed incarnates. But ‘religious feeling’ is not here as in the later instances, a violence to he body but a completion of it. And the word it incarnates is the word of a mass political potential, that already in Phil’s ‘speech’ before which Ed stands in embodied grace just as Paravicino embodies the Holy text of the religious books he holds next to his body.

I’d contest that, even though I ask these lines to do a lot of work here around the context of a famous painting in Boston, that the reading of Seth this supports, however tangentially, is far from fanciful. In a sense, what we are shown here is what Ed’s listening body looks like as, in the very next stanza he is introduced to Phil. Phil’s bisexuality is hardly a threat to Ed if we realise that what Seth is showing us here that beautiful bodies can incarnate the beauty of words of action and change, such as those which promote the defence of breathing life from the lifeless ‘zombies’ of ‘Lungless Labs’.

Hence the religiose tone of Seth’s presentation of the very real political action from the1980s that he presents most especially in Chapter 7. As for the protestors of that time, the world of nuclear weapons is our equivalent of apocalyptic Hell: ‘that day of wrath / When the smooth doomtoys hurtle forth’.[9] Even art itself won’t redeem us: ‘a weird vibration / Congenial to a brain-sick race’.[10] What we need is a spiritual recreation, replete with resurrection. Not surprisingly the main speech in the Lungless demonstration is delivered by a Catholic priest, Father O’Hare, as Phil reminds Ed, who has stayed away from the day:[11]

7.34

… Let me close

With Deuteronomy’s plain prose.

Here it is: “I have set before you

Life and death … therefore choose life.”

Or as that sign says, “Strive with strife.”’

For me, this long neglected poem remains important because it finds within it a means to life through the commitment to each other’s lives that each man could have given to the other in fighting for political space and life. Yet Ed is immature. His life is contained by values that neglect his own beauty and its effect on other men – bisexual or otherwise. Hence his commitment to Schwarzenegger the iguana, as ‘cold, and trembling’ as he.[12] After Phil’s imprisonment following the Lungless demonstration, he uses O’Hare to show that not all spirituality evades the needs of the living bodies of the present day:

8.3

…

You two should meet Ed. He’s compelling.

It may do you some good to find

A man of God who doesn’t mind

The temporal dunghill. …

So I think it appropriate to end this piece by speculation about why a poem of the 1980s, ostensibly about changes in relationships that by the end are only heterosexual ones, is in my mind a political poem with the Ed and Phil relationship at its queer unresolved heart. In the end queer literature was then, and to some extent remains, a censored literature. When Ed and Phil first meet their sexual hunger is clear. But ‘making love’ is easier for them to do than for a writer to write about it. As thing are ‘getting tenser’, Seth relates:

4.34

…

The imperial official censor

-Officious and imperious – drove

His undiscriminating panzer

Straight through the middle of my stanza.

…

Forgive me, Reader, if I’m surly

At having to replace the bliss

I’d hoped I could portray, with this.

What is the ‘this’ referred to at the end of these lines? Does it refer to ‘this’ intrusively narrated and voiced stanza that removes from the characters and what they feel of ‘bliss’. Or does it refer to the whole poem, which likewise must follow the censor’s line. That that censor is ‘imperious’ (perhaps after the likes of the Raj in India) and owns a tank as named in Fascist Germany sets the political tone. It’s worth noting too, though, that what Seth is saying is that the bliss of two lovely bodies ‘making love’ cannot be portrayed at this time, and hence our long poems and our long novels must be very different from art that aims to comprehend life without exclusions, especially the exclusion of the non-heteronormative. Or so, at least, I think.

Steve

[1] Seth, V. (1994:5) ‘Introduction’ to Mappings’ (1st ed. thus) in Seth, V. (2015) Collected Poems London, Weidenfeld & Nicholson. 5 – 7

[2] He uses the term ‘apology’ in stanza 5.5 line 1 whilst addressing the reader: ‘Reader, enough of this apology; /…’.

[3] Stanza 8.21

[4] See https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44703/modern-love-i

[5] Stanza 13.40. Only the omissions in brackets are mine.

[6] Stanza 7.6

[7] Pessisisimo (2013) ‘Reaching the end of the line: Vikram Seth’s Golden Gate and A Suitable Boy’ available at: https://exoticandirrational.blogspot.com/2013/10/reaching-end-of-line-vikram-seths.html

[8] See c. p. 126 and whole of Chapter 6 in Stoichita, V.I. (1995) Visionary Experience in the Golden Age of Spanish Art London, Reaktion Books.

[9] Stanza 7.2

[10] ibid: 7.3

[11] ibid: 8.2

[12] ibid: 11.7

Hello home.blog administrator, Thanks for the well-structured and well-presented post!

LikeLike