Queering the plot of the romantic novel: The role of the Rajkumar and other queer doings in Vikram Seth’s (1993) A Suitable Boy (with some reference to the 2020 BBC adaptation).

When vast novels like A Suitable Boy are televised we expect cuts, and perhaps compensatory minimal additions, that have an effect on the plot or even the range and/or role of certain characters. Indeed, in the novel itself, Amit Chatterji’s (Amit being almost certainly modelled after a part of Vikram Seth’s own character as a writer) ‘lack of compression’ is discussed. His prospective novel is predicted by a ‘rather fat’ lady to be: ‘More than a thousand pages’.[1]

But 5-part TV scripts demand compression. Even if we know the novel, we may not miss characters who appear relatively infrequently and with less apparent active role in advancing the plot of the novel. Very few early readers for instance will have noticed a character who is constantly named only by his social role, the Rajkumar or Prince. He is the son of the Raja of Marh, another person condemned by their weight of fat (of ‘bulk … thickly beaded with pearls and sweat’), whom from the start represents the worst aspects of the Hindu Zamindari, or right-wing landowning aristocracy.[2]

In as far as representing that political class goes, Davies is surely right that these functions of the novel’s politics are fulfilled without the Raja of Marh having a son. Yet a son represents the ongoing life and the survival, of a class too, as in the novel, The Raja himself says when he, ‘thinking of his ancestors made him think of his descendants,’ reflects on his son’s clear sexual preference for men. In the terms of the novel young men who have reached their sexual maturity are called ‘boys’ of course, suitable for heterosexual and generative marriage or otherwise. Even the way the Rajkumar ‘follows’ his father, in that father’s eyes, shows his inadequacy and unsuitability to that particular role:

… he looked with perplexed impatience at his son, the Rajkumar, who was trailing in a reluctant way after his father. What a useless fellow he is! thought the Raja. I should get him married off at once. I don’t care how many boys he sleeps with as long as he gives me a grandson as well.[3]

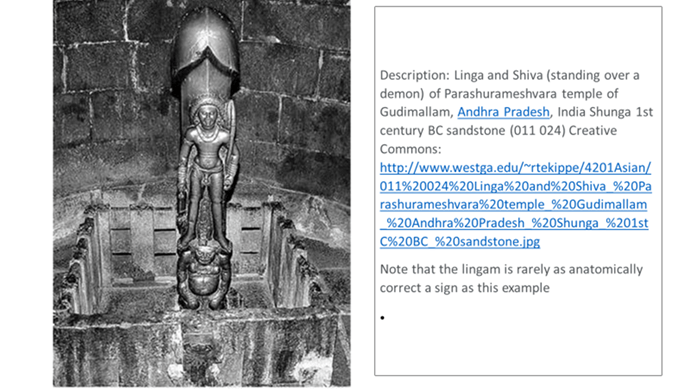

The point that failure of fertility is a prime problem in assessing the suitability of boys is just one way in which this novel is much bigger (big as it is) than the choice of ‘a suitable boy’ by Lata and Rupa Mehra when it tackles why and how boys are thought ‘suitable’ to their role, and that, I think, is what makes the Rajkumar central to it. Even when the Raja feels that he can fulfil his role in Hindu regeneration by enforcing an army of young ill-clad men to drag from the muddy bed of the Ganges and up the steps onto its bank a huge phallic ritual stone known collectively as Shiva-linga. They are not all as anatomically moulded to look like what they represent as the example below of course. The aim is to erect it such that the Muslim mosque worshippers when facing Mecca also face this symbolic phallus. In the novel he must do it with the aid of the Rajkumar.

The young Rajkumar of Marh, an arrogant sneer on his face, resembling that of his father, shouted ‘Faster! Faster!’ in a kind of possession. He thumped the young novitiates on their backs, excited beyond measure by the blood on their shoulders that had started to ooze out from under the ropes.[4]

This is a troubling scene in that it utilises the queer desire of the Rajkumar and perverts it into something violent and death-bound using the ritual masque of the phallic God Siva’s role in the destructive (since it involves death as well as life) regeneration. This sexualised power and violence is both masturbatory and bloody, and in pursuing it, the Rajkumar glories in the deathly sacrifice of young male bodies.

As a symbol to interpret, this is extremely uncomfortable for a queer critic who looks for imagery that allows us positive access to the role of the queer in literature and history. The association of queer masculinity for instance with infertility, pain and death is a homophobic trope. But discomfort is short-lived if we see the point here that the Rajkumar, far from becoming a symbol of queer sexuality has actually become a symbol of the link between masculinity and the structures of power and the state. The arrogance here is the arrogance of unrestrained male power to which all people become objects, sexual or otherwise. It is in this respect and at this point that; now more ever, his attitude to men is clearly ‘resembling that of his father’ rather than ‘trailing after’ it.

Indeed, we need to be good novel-readers here, to see that the Rajkumar is at this point a victim of the homonormative. He starts in the novel as ‘a basically decent man and not bad-looking but somewhat weak young man’.[5] That he, at the same place as that description, is said to also like Maan sexually hardly matters; his function being to represent one of two bifurcated moral poles ‘struggling for his soul’ as a man. The other pole is Rasheed: ‘One was coaxing his soul to hell with five poker cards, one beating him towards paradise with a quill’.[6]

He is expelled from a university, one that contained better models of male-to-male affinity such as Maan for instance, for the misdemeanour of visiting brothels with the wastrel straight boys he hung around with. Thus, the prince has been secluded for a long time from the influence of any man but his father, the Raj, whose sexual brutality, to his favoured courtesan Saeeda Bai, for instance, only matches his irresponsibility as a landlord and ruler.

Attitudes to ‘homosexuality’ were imported with the word ‘homosexual’ by the British onwards from the late eighteenth century. [7] Though privately ambivalent, in public, they were entirely negative in the imported institutions of government, such as public schools and government offices. This is shown in the incredibly significant but minor sub-story in which Dipankar and Amit Chatterji rescue their thirteen-year old brother, Tapan, from the lust of three ‘seventeen-year old’ boys in his school. Dipankar, who ‘knew the system from experience’, thinks of it as ‘invested with the power of a brutal state’.[8] This appears like exaggeration but is less so if one sees that this ‘brutal state’ was the British Empire and, in many ways, accustomed to initiate young boys as brutally and with no models of loving male to male relationship, as in the brutal court of the Raj of Marh.

I hope I’ve established that the Rajkumar is important in the novel – to its themes of suitable masculinity but also to the attitudes of others. These attitudes vary. Mahesh Kapoor is intolerant and describes him as the ‘pederastic son’ of the Raj of Marh.[9] On the other hand straight peers among the brothel-haunting ‘wastrel’ sons of the Zamindari are happy to describe him as merely being not ‘interested in that kind of thing’.[10] He is never seen as a sexual threat to Maan: even when the Rajkumar places his ‘friendly hand’ on Maan’s thigh, the ‘ticklish’ appendage is easily and without rancour on his or Maan’s part dismissed at the very point that the Rajkumar ‘moved’ that hand, ‘significantly upward’, presumably nearer to Maan’s genitals.[11] Indeed I think his main function in the novel is to confront the reader with his perception of the bond between Maan and Firoz as men who are considerably attached to each, and perhaps sexually.

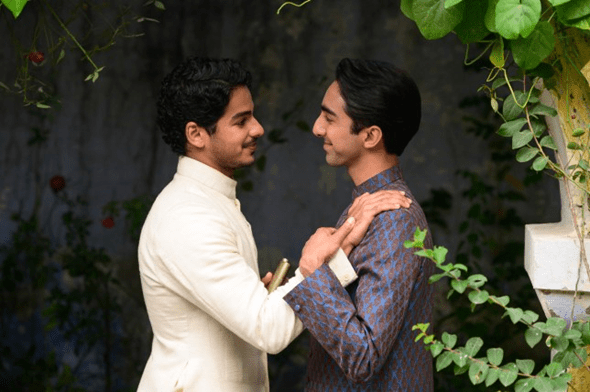

They are first seen together at a meeting between Mahesh Kapoor and the Nawab Sahib, a Muslin zamindar (large aristocratic landowner) to discuss the Zamindari Bill. It is the accidentally present Rajkumar who presents our point of view of what Maan, Kapoor’s son, and Firoz, The Nawab’s son, look like when together: ‘The Rajkumar of Marh, who was interested in young men more than in the jargon of the Zamindari Bill, looked at the handsome pair with a little approval’.[12]

Of course the reader need not view either of the young men in this pair as does the Rajkumar, but liking both men (as all the country people love him) seems to be a sine qua non of reading this novel appropriately. For me, the Rajkumar not only raises their profile as a couple in his own eyes but in ours.

Firoz’s role in defining Indian manhood is crucial to the novel. Towards its end, recovered from severe stab injuries and his youthful charisma beginning to fade, Firoz considers whether he is, is, ‘a man without attributes, very handsome, very forgettable’.[13] Indeed reflecting on this, I consider the theme of the ‘suitable boy’ as a somewhat wide-ranging set of questions about the attributes that make up a memorable and significant man in post-Partition India, one which questions that category in terms of what sex, gender, sexual orientation, class and status contribute to the need of nations and species facing large barriers to their continuing survival.

I stress this because I find the view that this is just a novel of character, a kind of compliment and complement to George Eliot and Jane Austen, whose novels are both read and discussed within this one, less than satisfying. Although definitively muted, this novel makes bold movements in its detail to query the efficacy of sex as a means of defining the worth of human actors.

When we last see Firoz and Maan they stand there together: ‘silent for a while. A rose-petal or two floated down from somewhere. Neither bothered to brush it off’.[14]

Nothing has advanced. Neither is much more than a symbol of a rather beautiful male-on-male semi-passivity, with much beauty but little action, not enough to knock off a petal from their kurta-pyjamas. This stilled picturesque male beauty that passes over two young good-looking men otherwise desired because of their active, if disengaged, dynamism is I think all we get from these men, who even by nearly 1500 pages of the novel fail to have much meaning that can be attributed to them other than to each other. Even at the opening, what we know of them is about their concern with being attractive, one that sometimes playfully questions issues of sex:

‘Don’t interrupt,’ said Maan, throwing an arm around him. ‘If you were to go down into the garden, a good looking, elegant fellow like you, you would be surrounded within seconds by eligible young beauties. … They’d cling to you like bees to a lotus. Curly locks, curly locks, will you be mine?’

Firoz flushed. ‘You’ve got the metaphor slightly wrong.’ he said. ‘Men are bees, women lotuses’.[15]

But are men only suitable when they are productive like bees, as the wonderful shoemaker, Haresh, who wins Lata, certainly is? Some men replace productivity with inactive continual cognitive and spiritual expectation of their future worth, like the younger Durrani. Some are productive in ways that wear out the man in his product – such as the poetic novelist, Amit. But if Amit is redeemed by producing art that is deeper than he himself is, Firoz and Maan do not produce art – they ARE art. And that art is the underlying and unfulfilled longing for each other.

When I say ‘unfulfilled longing’ above, this does not mean that I think them virgin to at least their sexual attraction to each other. That unfulfilled longing is more that of spiritual romance. It is like those lost traditions from the days of Aurangzeb, referred to in describing Saeeda Bai’s sexual strategies: ‘… Much Urdu poetry, like much Persian and Arabic poetry before it, had been addressed by poets to young men, ….’.[16]

However, when Andrew Davies, perhaps the foremost of openly gay male screen writers, re-read A Suitable Boy in order to write the recent BBC screenplay, he said:

I think Maan and Firoz have a delightful romantic friendship which at times has become physical, I think they’re both on that great scale of which we’re all on from all out gay to all out hetero. ‘They’re both slightly towards the hetero end of it but they have a delightful relationship. Sometimes I think it is classed as physical and certainly, I’ve been indicating that.

Davies cited by Yeates, C. (2020) ‘A Suitable Boy: Gay undertone between Maan Kapoor and best friend confirmed by producer’ in The Metro (26 Jul 2020 9:58 pm). Available at https://metro.co.uk/2020/07/26/suitable-boy-gay-undertones-confirmed-producer-13039983/?ico=more_text_links

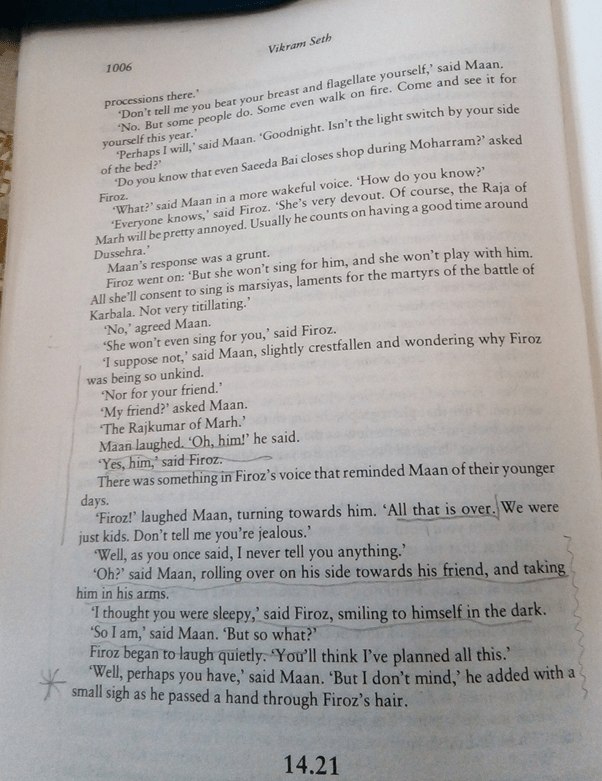

So far, so much agreement with what kind of queer sexuality best describes these young men, in as far as we think of them as types of young men who happen to be also characters in a novel. However, here I want to return, as these boys often do in their talk, to the Rajkumar. A key scene for me is the night these young men spend together in the vast rural Baitar Fort hunting animals and each other. Andrew Davies does not show this as a night scene but in the day where the boys just happen to lounge on the bed in what appears a very temporary interaction.

Davies also transposes the discussion such as it is given by Seth below, and reallocates some lines, so that the ‘plan’ the two mention appears to relate to Saeeda Bai rather than the opportunity for Firoz to receive physically expressed love from Maan, as I think it definitely does suggest below. The passage in the novel establishes that:

- The two boys had a sexual relationship when younger that is, at least for Maan (‘All that is over. We were just kids’), considered at an end, and if revisited, revisited only on a one-off basis this very night.

- That both boys use the easy sexual attraction to Maan from the Rajkumar as a prompt to a night when they will again come together sexually. They play at jealousy in order to play at a committed relationship, with whatever differences of feeling. Firoz seems to me to play with the less playful end.

- However playful, this passage is also heavily romantic like the rose-petals which fall on them at the end of the book. It speaks of a relationship in which both salvation and symbolic murder will later play a part in uniting not just them but two communal traditions in intent. The Hindu boys who attack the Muslim Firoz turn on Maan as a Hindu boy who ‘likes circumcised’ (Muslim) ‘cock’.[17]

In essence this entire reflective consideration emerges from the way the two boys in the scene I give from the novel below (p. 1006) use the role of the definitively gay Rajkumar in relation to that light of heart somersaulting nice boy who is Maan until forced to see how serious might be his relationship to Firoz (a life and death matter).

But it is also about why in a long novel we can’t assume that some characters, themes or episodes don’t matter – including the vast number I purposely also don’t mention here. They can and do matter but no translation into a different medium, even critical thought like this but especially TV with all its other determinants, can ever satisfy every facet of a great novel. What I would query is Davies’ solving the problem of the two boys’ relationship by placing them on a gay male continuum of individual types. The problem for this novel is not how to represent these characters’ sexual orientations as individuals but how to represent real love between men in the art of a largely heteronormative world as an element of a novel that does many other things.

Steve

[1] Vikram Seth(1993) [pages from 3 vol. ed. October 1993] A Suitable Boy London, Phoenix House: 1254.

[2] ibid: 1318.

[3] ibid: 704

[4] ibid: 1318

[5] ibid: 333

[6] ibid: 337

[7] This case can be amplified through scholarly channels but I don’t feel thus bound here. They can be seen even in Indian psychiatry, which is similarly burdened by British imports. See https://www.apa.org/monitor/2019/02/homosexuality-india. Seth does include some of the evidence of acquaintance with LGBTQ+ traditions also utilised in the West, around transgender role-play in Shakespearean theatre for instance (a lovely instance in ibid: 780), but also that based in comic folk narratives (ibid: 1232) or snotty upper class mandated tolerance of the ancient traditions of the Hijra and their role in marriage ritual (ibid: 1347).

[8] ibid: 1097

[9] ibid: 754

[10] ibid: 786

[11] ibid: 342

[12] ibid: 331

[13]Ibid: Apologies but I’ve lost the page reference.

[14] ibid: 1341

[15] ibid: 19f.

[16] ibid: 84

[17] ibid: 1060.

This is very interesting Steve thank you

LikeLiked by 1 person