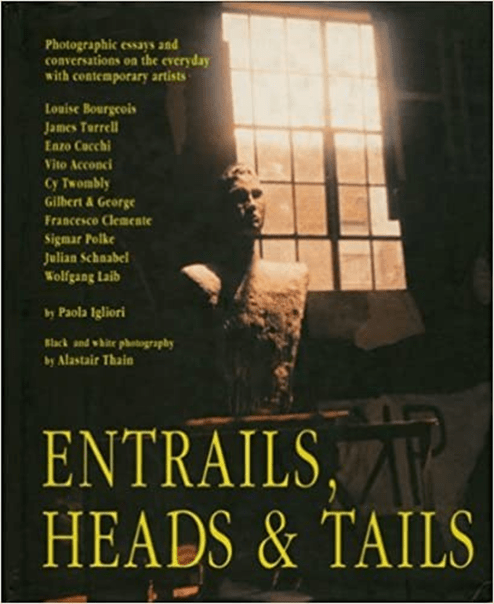

Sense and Nonsense, Determined or Free: Making sense of a subjective project that is the making of Paola Igliori’s (1992) Entrails, Heads & Tails: Photographic essays and conversations on the everyday with contemporary artists New York, Rizzoli International Publications

This book could be seen as a map that indicates some extreme point of entrance to the core of expression and takes us past it. It is also a discourse on prison and freedom, on how far a human being can go with himself, and on predetermination. … I started working on this book almost unconsciously – in all my life I had never developed the instruments that most people develop to bridge the chasms within. ..the going hand-in-hand of death and life, destructiveness and creativity … . Contraction: our experience of being born repeated throughout our life: fear, aggression, passivity, difficulties. And then the expansion: the flow – the ever-reborn second – in which we are one with the action, whole, movement beyond the mind.

From Igliori, P. (1992) ‘Introduction’ in Entrails, Heads & Tails

Some books are designed to create an aura of estrangement between a reader and their expectations of ‘a book’. The extract from the book’s introduction, which I cite above, merely adds to this sense of estrangement – of ‘mapping’ (the metaphor’ she uses above) an arena that is unknown, unfrequented and whose features might be relatively unconscious rather than grasped cognitively. A minor point about estrangement from normative book conventions is worth making from the start. This book has no page numbers and cannot therefore, itself, be mapped cognitively or by external reference as readers are wont to do. It is as if, we must ‘map’ our way differently in this ‘terra incognita‘, as she was to call it in 2016.[1]

What is the book about? If we take the title, for instance, associative and interpretive work is already demanded. ‘Entrails’, the innards of an animal, including a human animal, refer of course to the bloodied freshly excavated viscera of the internal organs as well as what it is within, in contrast to the ‘heads and tails (or remnants or metaphoric substitutes thereof of the latter in human animals) which are evidently external body features. Yet none of this is spelled out in the introduction, which stresses the need for unmediated responses to the books epistemological contents (the knowledge it contains) and their relationship to its external ontology as a book (what the book simply is).

By 2016 Igliori is obviously prepared to mediate between the book and its readers a little more as she shows in an Italian interview with Manuela De Leonardis. She refers here to her her response to the ‘great pain’ of the termination of an impossible relationship with her fist husband, with hints of the self-harm and cutting with which it was expressed, as the tumult of internal and external worlds, like armies ignorant of each other, clashed together at night.[2]

Questo grande dolore mi portò ad un’instancabile ed inarrestabile esplorazione di quella terra incognita da cui scaturisce la sorgente dell’ispirazione. Però, solo dopo aver realizzato il libro – il mio lavoro procede sempre in modo organico, non so mai dove va a finire – capii che allora era stata una necessità, per me, entrare nella quotidianità degli artisti. Il titolo è altrettanto significativo: in italiano vuol dire viscere, teste e code. Volevo affrontare le pulsioni creative, la visceralità, la sessualità, la mente e il cuore. Cercavo di capire se la creatività e la distruttività devono andare necessariamente mano nella mano, oppure no.[3]

This writing makes access to the pulse of blood clearly easier in the terms ‘le pulsioni’ and ‘la visceralità’, but there is also the ‘head and tails’ to make senses of. It is a rich colloquial idiom in the English chosen by Igliori with the implied meaning of making sense of nonsense, such as top and bottom, head and tail are seen in the organisation of things physical and organic. Another meaning associated with ‘heads or tails’ is the act of deciding a binary choice by the toss of a coin and this association with chance, makes me conscious of the classical use of entrails as texts in which the decided will of the Gods could be read, known as haruspication. I think therefore the title indicates much that Igliori later glosses – that we will look within (inside the spaces in which artistic creativity and the the objects of their everyday life are in balance for artists) for clues of whether we can know anything about whether human work is freely associative or determined. If art is determined by a search for meanings, we might look for these in the human spaces between where artists live in the own everyday world, semi-created spaces in which they interact, even if by minimising interaction as in the case of some (I’m thinking of Cy Twombly) with others.

During the several years that I have owned this book with its conversational interview contents, I have consulted it more often to gaze at its ‘photographic essay page-sequences’, especially those recording Twombly, the only ones with no interview or explanatory material at all. Twombly was interviewed for the book at length like the other ‘subjects’, but, in the end, Igliori reveals in a 2016 interview, ‘mi chiamò al telefono e mi chiese di non pubblicare niente di tutte quelle parole’.[4] Twombly’s refusal to mediate his art with clearer explanation may have much to do with his well-know secrecy about his private life but it is a path that leads us nowhere with our interpretation of his art. Instead, we might see his reluctance to mediate his art with words is entirely at one with the intentions of the book itself, that meaning should be free to achieve its own level in interaction with any person who may who hold the book and looks and ‘read’ (if that is what they do) for themselves rather than having their interpretation determined by the authority of a creative or critical external voice.

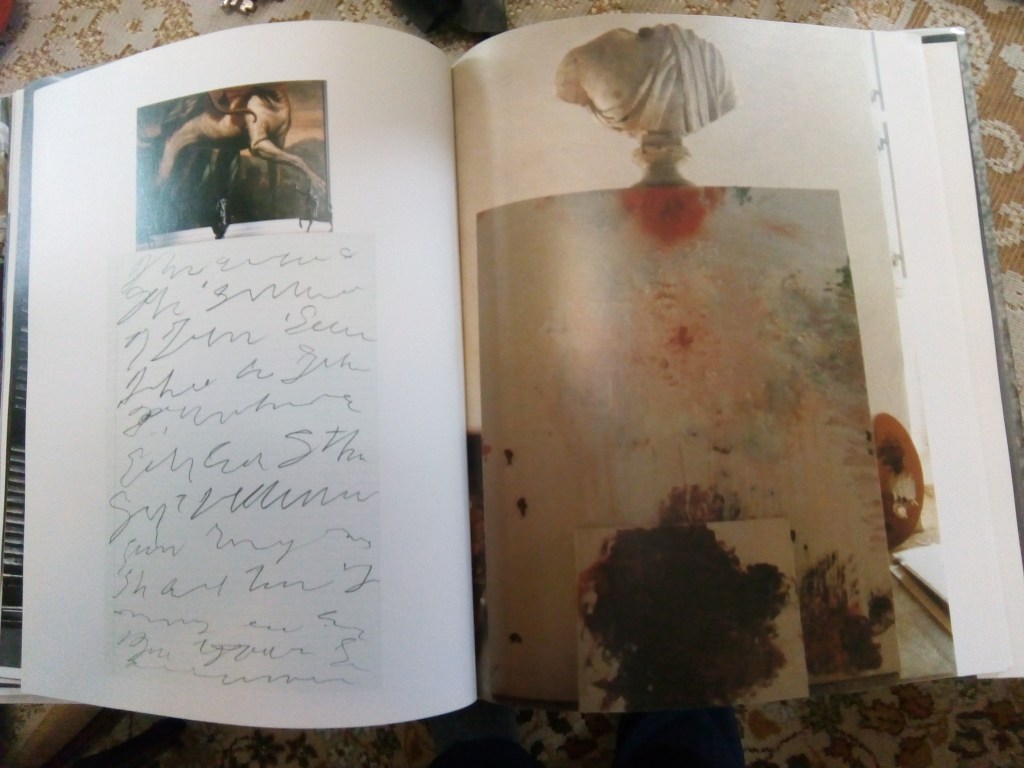

Given that Igliori’s introduction does urge us to do something with our freedom, why should we not do just that and, as she says in her 2016 face what we don’t know or understand, ‘con i ricettori tutti aperti’ (with all receptors open). It is typical anyway of Twombly’s work to make work look accessible in ways that it is not. See, for example the one double-page opening from the ‘photographic essay’ on Twombly below.

Our difficulties in understanding relate both to the spacing and of the graphic images on the page and to the images within each graphic image.

For instance, start with the photograph at the top of the first page here. It takes time to see that it is a detail of a room taken from an angle that both baffles and confuses us about its ‘subject’. So partial is our grasp of the scene or of our viewpoint on it that we must struggle even to grasp such as perspectives as render consistent senses of depth and distance. I puzzled out, for my own temporary but not secure satisfaction, that there is a furniture mantel upon which black figurines stand, of which the two extremes ones seem to represent classical centaurs. The central figurine is so confused with what might be colouring or other shading in OR on top of , in the form of a shadow, the graphic behind it. It appears to represent some fantastic animal with possibly a rider but still looks to my senses nought but shades of black and white chiaroscuro.

If the juxtapositions and gaps between objects confuse me, I found that magnified in the layout of the two printed figures on this page. The photograph of a scene of mixed representations seems literally pushed against, with no gap – or ‘gutter’ – (such as one would expect between separate figures on a printed page) in order to indicate their independence. What we are left with is the possibility that these figures are not independent but have some link or association.

Yet the lower graphic is equally inaccessible. It appears to be lines of prose writing and some marks seem to invite us to ‘read’ them, sometimes with partial success, or what me temporarily seem such. For instance on line 5 I felt I saw the abbreviation ‘5th’ before noticing it might more likely be that for Sthern (‘Southern’ where the superscript form ‘th’ is broken up so only the ‘t’ remains in superscript, whilst ‘h’ is with in the form of the tail of the adjectival form). Many people shown them identify other specific words or abbreviations. Even, at the risk of having been seen to have failed to ‘read’ what is there, few can really say that is much more than it is, in the end, illegible writing, writing that cannot in truth be ‘read’ and remains nothing but a visual representation of writing with such meaning as derives from that visual data alone.

This relationship between the panels containing separate graphics can also however associate with the internal representations of the larger photograph on the second page, where the relative independence of different panels becomes an issue as does the nature of objects. Is, for instance, the painted surface a panel painting leaning against a plinth, as the smaller panel leans against it, or the painted front of a solid object on which the fragment of a headless Roman bust stands. I would say that the issue of what is standing in front of or on top of what has become an issue in comprehending the visual codes across these pages. As a result other associations and contrasts emerge in the photograph on the right particularly around formalised and literal representations of the body. It’s hard not to see the reds and pinks as figuring out a bleeding and blood-filled body that is so unlike the stone replica above it. A red heart seems near the surface of the tonal display surrounded by a penumbra of pink skin. Below is visceral waste and excremental brown smears.

My reading replicates I would argue those dualities which Igliori felt she needed to bridge in her introduction – between dead material and organic living flesh, the static and that which flows across boundaries , destructive fragmentation and holistic creation and finally between various intersecting domains of what is intuitively felt and sensed inside and what is objective, in the form of separate objects with clear boundaries, in the outside and everyday world of the knowable. Of course bridging these dualities means recognising their possible admixure at their seams, a metaphor Igliori also uses in her 2016 interview.

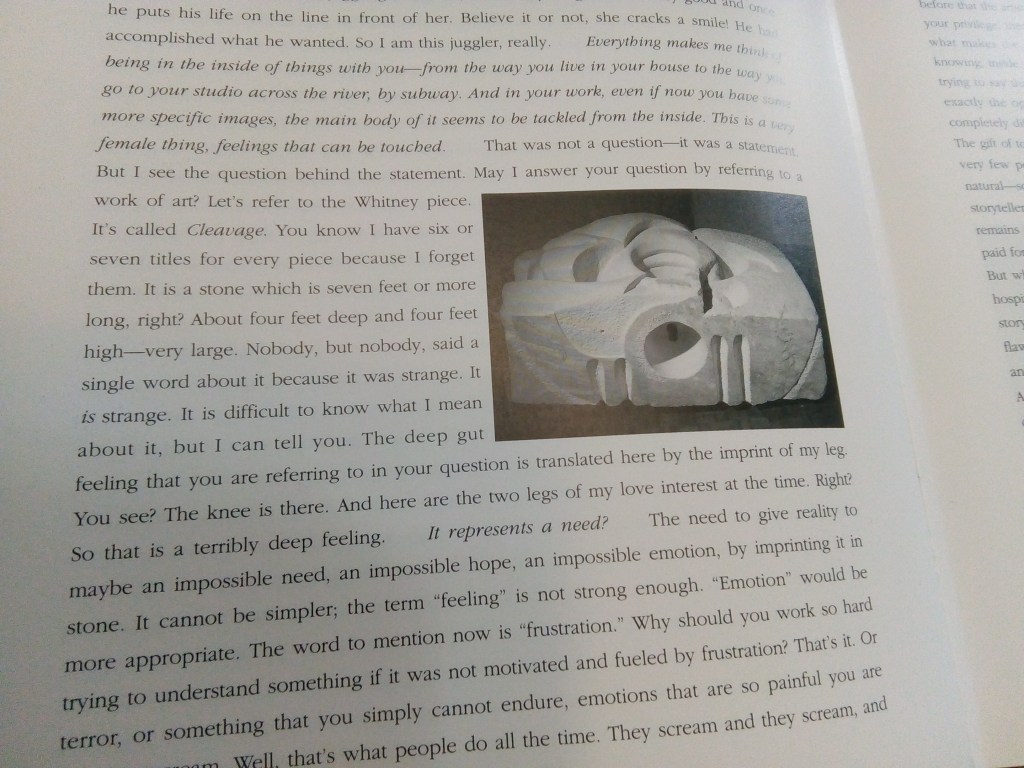

However, to establish how this happens across the many varied types of inside and outside comparisons made by the artists she features in this book. They are at their most approachable for me in two of my most favourite artists she choses: Cy Twombly, whom I’ve mentioned above, but also her first chosen subject, Louise Bourgeois. Bourgeois did allow her interviews to be published and Igliori’s seems at her nearest to this artist of fragmented body parts and things felt from the inside. We see this proximity in the photograph below of a section of that interview with an inset photograph of the artwork by Bourgeois they are discussing.

The photograph inset is unlike the version of Cleavage of 1991 and may be an unfinished copy or earlier state kept by Bourgeois. Hence I give a contemporary photograph below, where the organic features such as those mentioned by Bourgeois appear more obviously.

However, this is immaterial to my point, which is to show that a discourse of the body which inbuilds an interior perspective that symbolises unseen and repressed emotion and thought as a function of independent female sexuality that it is still difficult to see regarded as important in public art. Bourgeois sees them as disregarded even in even critical accounts of her art and as difficult to bring into public life other than by transmissions of empathic feeling and sensual knowledge between women who know the ‘frustration’, as Bourgeois calls it, that erased complex but real, non-conforming sexualities involve.

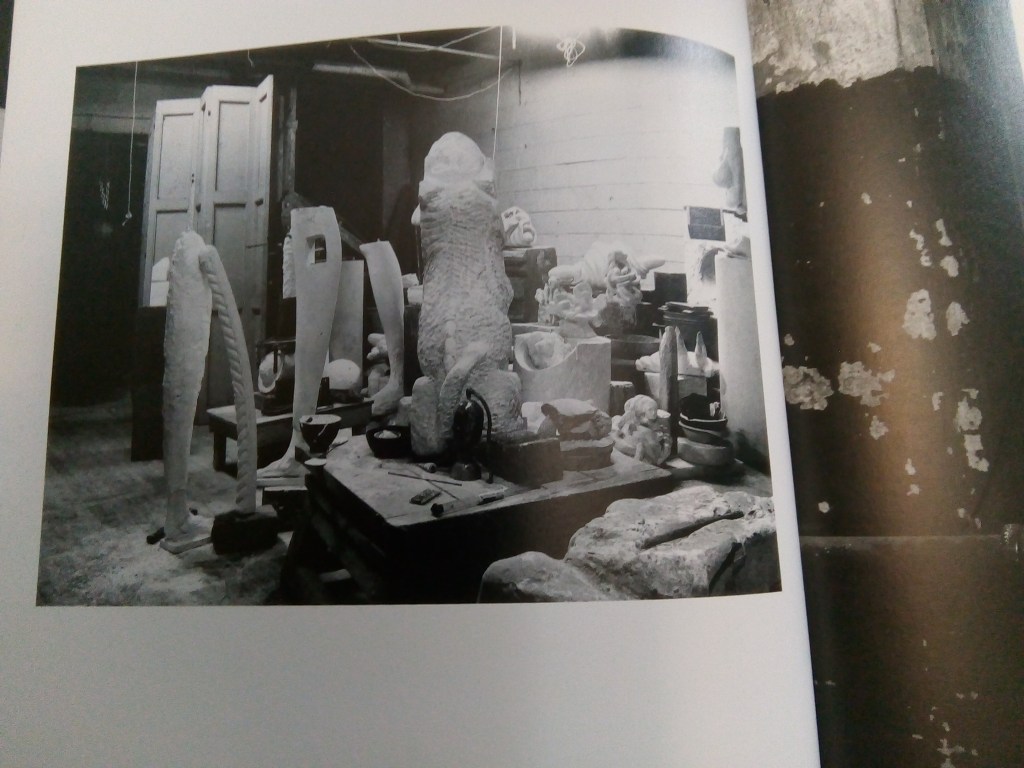

When seen within Bourgeois’ home, these yearning organic wrinkled but hard looking structures combine intuited softness, even the phallic tailed animal seen below, with their very threatening intrusive hardness and weapon like quality. Bourgeois’ home here islands them in front of the flexible folds of a screen. And light in this everyday scene in Bourgeois’ home falls on a soft cleft carefully and smoothly carved out of stone.

But strangely enough, I don’t feel I’ve got to where I wanted and made this book appeal to others as it appeals to me. Hence, I’ll just leave it as a recommendation for the book and those artists.

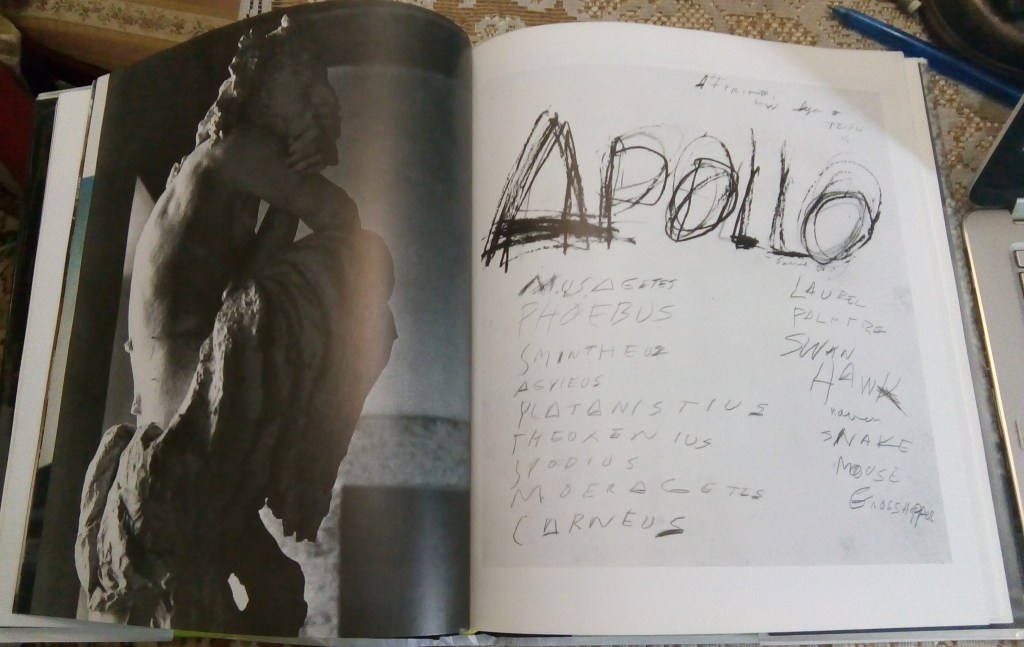

And perhaps I can also leave without commentary another dualistic view from Twombly where what looks like a satyr, perhaps Marsyas, confronts, for the purposes of Igliori’s momentous book, the conceptualisation Apollo on the facing page.

[1] De Leonardis, M. (2016) interview available at: https://www.artapartofculture.net/2016/08/14/paola-igliori-poetessa-e-scrittrice-fotografa-e-filmmaker-manager-culturale-inesauribile-viaggiatrice/

[2] With my apologies to Matthew Arnold’s Dover Beach.

[3] De Leonardis (op.cit) Google automatic translate gives: ‘This great pain led me to a tireless and unstoppable exploration of that terra incognita from which the source of inspiration springs. However, only after making the book – my work always proceeds organically, I never know where it ends – I understood that at that time it was a necessity for me to enter the everyday life of artists. The title is equally significant: in Italian it meansviscere, teste e code. I wanted to address the creative impulses, viscerality, sexuality, mind and heart. I was trying to figure out if creativity and destructiveness must necessarily go hand in hand, or not.’

[4] ‘he called me on the phone and asked me not to publish any of those words’. From De Leonardis, M. (2016) interview available at: https://www.artapartofculture.net/2016/08/14/paola-igliori-poetessa-e-scrittrice-fotografa-e-filmmaker-manager-culturale-inesauribile-viaggiatrice/