‘”… we overload summer most out of all the seasons, I mean with our expectations of it.”

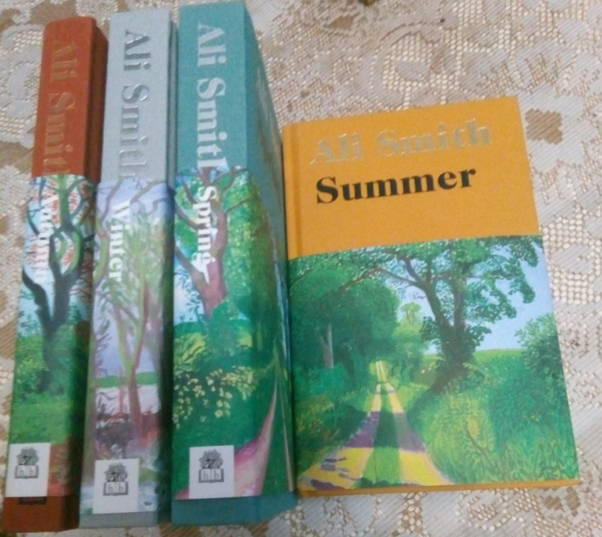

“… Summers can take it. That’s why they’re called summers.”’ Reflecting on Ali Smith’s (2020) Summer London, Hamish Hamilton

How long have we hoped for and expected the arrival of Summer? Since, at least, the Autumn of four years ago. That’s a time space in which it is clear at least two different interim summers have each predicated a novel published in its appropriate season, such that one summer’s succeeding winter became Winter and then Spring came before the summer preceding this summer’s Summer. Even such a cursory description of the publication history of this great modern four volume shows why this, and the other novels, play games with time. Except they are games forever associated with art: where time might variously be represented as an icon or symbol in background or foreground, in setting, figures or objects, imagined spatially as a lateral, vertical or mixed sequence, or depth effect or as variation of expectations such as might be brought about by anachronisms or temporal oxymorons (of which a good example might be the central place in the narrative cycling of Summer of visits to ‘Winter’s Tale Summer 89’).

Even subjective impressions of any one person, which in their sequence are vital to the structural and semantic impact of any novel are based on the dependence of such impressions on universal universal animal cognitive processes such as memory and anticipation.[2] Many of these effects in literary art are effects of language and have always been at issue in Smith’s fiction and quasi-fiction. And that might be because we cannot tell stories without the sense that, in the vey telling over whatever duration that takes, stories relate to our power to control the meaning of passing time, whether in the relative permanence, or inertia, of some art, the maintenance of optimal control in a narrative strategy that apportions no agency of their own to the retrospective or prospective in the storyteller’s imagination, or the eradication of the events in passing time upon meaning in the phrase ‘So what’ (abbreviated in this moment of passing time and fashion to the term, ‘So?’), a meditation on which opens the novel.[3]

And the ‘Winter’s Tale Summer 89’ instance is an excellent example of that, in that the fact that even art takes meaning from the contingent effects of its re-presentation (it’s presenting again in a different context) where contingencies include not only re-interpretations of the past, but the events contemporary to the presentation again – whether the events of 1989 or Brexit or Lockdown. This is complexly part of how we read. Grace, for instance, takes meaning from the play on her name and its association with Hermione in the Winter’s Tale and the reunion of a blessed Mother with a lost child, Perdita [the name that might be given to all those lost, estranged and outcast children produced by the lack of adult governance]:

… she has to hold the statue pose while they all look at her, first as a statue, then as a living body, and 120 lines before her cue to speak: turn good lady our Perdita is found. She gets lines ready in her head:

You gods look down

and from your scared vials

pour your graces

upon my daughter’s head.

…..[4] My italics for ‘graces’ only.

This beautiful moment is an icon of how time is redeemed in art of course in the standard interpretations of the play, wherein deficits in human behaviour from the past are mended morally and time is stilled or held ‘in statue pose’. Hence the concentration of how Grace here both presents Hermione in techniques of mimetic art in which she must be an artwork and a ‘living body’, each of which is a variant of art and artfulness.

Grace is merely one of the graces poured down by art to cultural transmission through her own children in the messy present. It is how the meanings we give to time past and time future in time present work. And how skilfully the memory of Grace enacting Hermione in the Winter’s Tale emerges in Smith’s own telling. It emerges as a necessity and a contingency in the narrative.

- It is a necessity, because the story is fixated at this point on motifs of a mother reunited with a lost child that are difficult to interpret. They refer to a sculpture by Barbara Hepworth, whose mother and child parts had been separated. It is owned by Daniel Gluck who was interned as a political immigrant with Kurt Schwitters and Fred Uhlman by the British in World War2, and whose stories have just been told in the novel. Daniel himself first appeared in the novel in Smith’s novels in the first section of Autumn.

- It is a contingency because the pursuit of Daniel, itself locked in the present novel and in the preceding one Spring (in which the theme of internment comes to prominence). The contingent connection to The Winter’s Tale is that the Hepworth statues mother and child parts are reunited In the very place where in the past the Shakespeare play The Winter’s Tale had been played by Grace. This prompts Grace to remember her past enactment of the play, precisely because her mind is looking at that very point to be ‘back into a story she could take some control of’.[5]

- Never has necessity and contingency – the very stuff of novel writing – been so well linked.

It was the old cinema –

and this was the point at which a memory, one she didn’t know she had, cracked open inside her head like the green of a seed cracking through the husk around it –

backstage in the little town cinema,

…

1989

summer of discontent,

they’re doing a two night run here, Shakespeare tonight, Dickens tomorrow.[6]

The metaphor of return from an imprisoning husk of a renewed life that is also a lost memory is one of the ways narrative too manipulates time and its sequences here, and it helps Grace to find meaning and a sense of control over her life, including its future with her own children. But she does this precisely because there remain elements of which she is not in control that are prompted by a Barbara Hepworth sculpture.

Hepworth’s sculptural meme of Mother and Child recurred throughout her work but I’ve chosen one with two semi-autonomous stones to illustrate one like that described in Summer. Hepworth’s interest was itself associated to her own deep interest in memory archetypes of mother – child relationships, that, though built into her own autobiography, was influenced by the Kleinian psychoanalyst and art critic, Adrian Stokes.

Smith shows how, after witnessing the reunion of the stones which compose a Hepworth Mother and Child in the hands of Daniel Gluck who had once owned both of its parts, it prompts in Grace a dream-like experience of her ongoing relationship with her own dead mother. The passage also utilises 2020 contingent material about the mortal fears associated on our present with face masks:

A mask of her mother’s face beyond both life and death, beyond happy and sad, alive and dead at once – no, not at all dead, nothing dead about it, not in any way. … Next to it a smaller stone mask was the face of Grace’s fourteen year old self, the age she was the year her mother died … In her head as she walked along the pavement the two faces sat blank-eyed next to each other.

Ali Smith’s attempts to capture how the unconscious in memory might work in art and how art might itself also prompt its unconscious source material, by creating complex troubling and anachronistic dream-like scenes. Here the main aim of anachronism is bring the agency of the dead and a dead past into a present, and possibly future life. It is how certain very difficult-to-read stories make sense of our experience of time. And its use will be to link Grace’s unworked through material in her relationship to her dead mother to the ongoing relationship to her own daughter, before she herself dies.

I wonder if I can really convey above both how complex and how significant Smith’s self-conscious story-telling is and yet how connected to everyday experience. Summer has got me nearer to this than I’ve ever been. Smith seems to suggest this in an essay she wrote recently for The Guardian:

So what happens when you tell some of the stories of the time and space between the coining of the words “Brexit” and “Covid?”

Time, art, though, history, language; who gets to speak and who doesn’t; people real and fictional and how their stories are and aren’t told; ….[7]

Ali Smith’s statement above clearly states her fascination of a storyteller with the politics of voice: the terrain in which claims are made about, for instance, about ‘cancel cultures’ in which some noisy and powerful voices claim they are silenced at the same time as they actively suppress or do nothing to ensure untold stories of the truly marginalised and disempowered in unequal societies are not told. Dominant cultures and social groups can be thus described because they negate, in often very subtle ways, the voices of those who challenge that dominance.

Those voices and stories are often not literally silenced but pressed into the margins of the unconscious, forgotten or lost through the actions of time and selective significance where ‘now is not the time’ to be heard. Lost stories in all of the Ali Smith Seasons Quartet are often tied to the themes in national consciousness of this and other periods of exclusion and internment. Whilst thrown into the contemporaneity of the novels telling of stories of Brexit and immigration control, the novels insist on anachronism in order to show silenced voices had already spoken of those themes.

Hence in summer the vastly important place of the artists Fred Uhlmann and Kurt Schwitters (anti-fascist political asylum seekers) whom Britain identified as ‘undesirable aliens’ and interned. Such stories and their relevance to contemporary debates are oft forgotten and made to seem like irrelevant episodes in a dominant hi(story) of British fairness. This is I think why each of the novels choses an artist to resurrect whose work challenged dominant cultures using ‘othered’ and silenced voices but whom are now rarely remembered, from Pauline Boty of Autumn to Lorenza Mazetti of Summer. Indeed the ‘deaf mutes’, one of whom was played by then unknown sculptor Eduardo Paolozzi , of Mazetti’s major film, Together (1956) make massive appearance for this purpose in Summer, of which more later.

Summer explores untold tales and silenced voices in so many ways that are transparent and obvious. Less so is the way it demonstrates how social mechanisms in dominant culture like the attribution of original, and therefore definitively challenging, thought to the ownership of individuals, rather than communal shared, ownership. Those functions in thought of attribution fuel the massive psychosis about referencing in modern academia and have challenged what were originally more communal forms of the ownership of thought like Wikipedia and other internet communal sharing of ‘free’ knowledge. The battle cry to force ‘acknowledgement of one’s sources’ may seem a specialised one but Ali Smith makes it matter at focal points of her novels – novels which search and utilise thought as a means of taking an attitude to social, political and personal change.

For instance few novelists cite the thought of the past as obviously as does Ali Smith, the other obvious example I think being A.S. Byatt, a champion of Smith’s writing.[8] Novelists who use past writers and artists, whether well-known ones or otherwise, take liberties with those sources of thought for their own novels, moulding the former writers’ themes and analyses of the present with their own ends. Using older thought that refers to a different contemporaneity in a new temporal context, that of the present and future, is a means of reviving it, making it useful for today and the audience to which it is addressed.

This is what even the youngest writers might do in their beginnings and many of Smith’s young girl characters are novice writers, be it only for a school essay for the moment, pressed most especially by external deadlines. The very deadlines, it should be noted that Smith invented as a temporal dynamic for her writing of her four seasons novels – publication date being in the appropriate season of each of 4 consecutive years with therefore only one year thence allowed for writing, proofing and publishing.

Sacha in Summer, for instance, harassed by deadlines and aiming to meet criteria in her audience, must take on board, for instance, a nuanced approach, subjectively new to Sacha, to the concept of ‘forgiveness’. She does this through a ‘quote’ from the website, Brainyquote, without knowing or caring that the sentence taken is attributable to Hannah Arendt.[9]

The quotation from Arendt (‘ Forgiveness is the only way to reverse the irreversible flow of history’) is, in fact, seminal to the way that Summer, and its companion novels, play with notions of time, temporal sequence and temporal order. Even the word ‘devoutly’, which Grace queries as adequate to the quotation (‘it sounds more philosophical than devotional’) will play a part in the novel, in as much as it takes the ritually redemptive nature of linking ‘Grace’ (the virtue) and the reversal of the cruelties of experienced history, including exile, displacement, migration and separation anxiety, later in the novel. It is forever united by the motif of the lost daughter that links Grace and Sacha to Hermione and Perdita in The Winter’s Tale, Schwitters mouldings from waste porridge and Barbara Hepworth’s various Mother and Child statues.

This is all the more important though in that Ali Smith makes this scenario focus on a believable and everyday debate between mother and child about attribution and acknowledgement of accurate ‘sources’. Smith invests Grace with conventional ideas about being faithful to source, that convince because of our knowledge of her university education.

…. What’s the source?

Brainyquote, Saca said.

That’s not a source, her mother said. Does it give the original source? Look. It doesn’t. That’s terrible.

The source is Brainyquote, Sacha said. That’s where I found the quote.

…

You need better source reference than that, her mother said. Otherwise you don’t know where what Hannah Arendt said comes from.

…

Yeah, but I don’t need to know that, Sacha said.

Yeah but you do, her mother said, Check and see if any of those sites mention a primary source.

The internet is a primary source, Sacha said.

…. (my omissions – they should be restored if you want o see the authenticity in Smith’s dialogue)[10]

This is not only a debate filtered into the everyday from the present psychosis in teaching universities about attribution and referencing in academic culture and its conventions – ones rooted, I believe, in ‘them and us’ distinctions and contradistinctions of value in which the academic is differentiated and seen as more valid and authoritative than everyday discussions.

Thus Grace’s ‘Yeah but you do’ mimics the teenagers stereotyped filler (‘Yeah, but’) and in doing so asserts authority – a command that sources can only be what an external academic tradition demands they be. And this argument is also an argument about time and authority or in Smith’s earlier terms, ‘who gets to speak and who doesn’t; people real and fictional and how their stories are and aren’t told’.[11] Adults impose on their children the values of the world that were in their earlier turn in the cycle of generation imposed on them by a world constituting itself in these rules and which it disguised as realities. Sacha’s world is as intellectually valid as Grace’s world we will acknowledge if we enjoy and appreciate such exchanges appropriately. Reading it helps me to query how and we organise thought in a way that demands that all ideas are traced to an ‘original’ source, a person locked down in the past by attribution and referencing placement, in the past and not treated in terms of their usefulness in the present and for moulding possible alternative futures, as we shall see Sacha doing later in this novel, restoring to Grace the grace to act rather than re-present the message of The Winter’s Tale.

Ali Smith shows further interest in the term ‘source’ later when she tells the story of Hannah Gluck who helps political migrants who seek British names from graveyards: ‘This was a good source’, because the data they contain are usually held in two different categories of information, namely birth and death certification.[12]

You see the name and the dates on a stone.

You ask a silent permission of the person gone.

You bow your head to their memory.

Then you pass on the gifts, the names and the dates, to the person who needs the new self.[13]

What has happened here is that a ‘source’ is validated not as an end-stopped occurrence in the past – one of the functions of academic referencing – but as information given new present use and a life in the future. This is how young Sacha wants to use Arendt’s aperçu.

Smith uses this coded paradigm even to distinguish her own authorial narrative voice in the novel, in a passage that may strike the academic reader as bold, given it apes their discourse otherwise in introducing the forgotten work of Lorenza Mazzetti:

I can’t remember where this next quote you’re about to read is from. It’s nothing to do with Mazzetti, though it’s everything to do with her, and us all. but I copied it into a notebook some years ago and now I can’t find its source.[14]

This is an author that plays with words. The point here is that, as in Sacha’s earlier insight, no source is ‘primary’, or automatically the top of an evaluative hierarchy, because of a person, work or time IN THE PAST to which it is attributed in reference, rather it is validated in its usefulness in its present context. Do readers silently upbraid Ali Smith’s narrative voice as Grace upbraid the young writer, her daughter, Sacha: ‘You’d have to go through all those sites until you find what it is they’re actually quoting from. Context. It matters’.[15]

Looking at this last quotation in contrast to Smith’s playfully innocent voice above we see that it’s a radical re-interpretation of the word context. Creative novelists create their own ‘contexts’ for an utterance, even a quotation, not rely on one it was purported to have been by dint of academic retrogression in the past.

So again this theme is about time. We see it in the way that Grace only gradually learns what the significance was in her youth of her drama group taking a primary source like the literal opening of Dicken’s David Copperfield and changing it so that it is about how women rather than just male writers have to routinely refashion themselves.[16] It is about how writing can take the past, whether stored in print or cognitively as memories and regrets and CHANGE it, by re-finding what it had lost through timely processes – its original significance. In the same way, a migrant takes a name and dates for the same purpose of giving it present and future meaning with the aid of Hannah Gluck.

Even contemporary politics stories play games with significance and the ‘consequences … of the political cultivation of indifference’.[17] Our obsession with primary sources can obviate from a concern with how we apply standards to the use of political discourse now: ‘the lying, and the mistreatments of people and the planet’ that characterised the Brexit campaign, climate change politics and now, Covid-19.[18] Hence Smith’s desire to resurrect the truths underlying the lives even and perhaps especially, of forgotten and marginalised artists in each of her books.

The biography of Lorenza Mazzetti and the description of her art which shows her art focusing on the significance of London and a migrant with it both:

having to rebuild themselves in those years nearly a lifetime ago, after the tens of millions of people of all ages across the world had died before their time.[19]

That this quotation itself quotes the most empty phrase used by a Prime Minister to unconsciously predict the effects of his Covid-19 preparations makes it all the more poignant and moving. Smith uses Mazzetti’s ‘moving image’ of a man balanced above London on a thin roof ledge from Mazzetti’s Together to literally ‘move’ us by not quoting ‘a still or a photo’. This play on the meaning of move might be seen better if I provide that still in Smith’s stead.

Mazzetti and her films resonate through the novel as a few page references can show the reader without overt over-quotation.[20] The more difficult operation is to show how the re-finding of Mazetti’s work links to the refinding of Daniel Gluck by Hannah, the union of mother and child Stones and the finding of Perdita in The Winter’s Tale. It is about reversals of time, not just history, by the rediscovery and reanimation of past relationships. It is an attempt in art to prove, in the darkest hours of our history over the four years of this novel’s completion that ‘time had (not) quite undone us’. ( a silent citation of course from that part of T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land where the poet himself cites Dante’s Inferno.

Where’ve you been all this time? he says.

The traffic was busier than they thought it’d be, Hannah says.

But so very long, Daniel says. I thought time had quite undone us.[21]

Time plays a part in wounding and healing in very obvious ways in this novel as Robert Greenlaw’s autistic experiments with it show (as he proves it can harm his sister by supergluing a timepiece to her hand) and in saying it has a multiple nature and is ‘dimensional’.[22]

But what seals Smith’s play with time in this novel is her constant insistence that she can reinvent summer as a symbol of hope for the present, even in the year oF covid-19 and the onset of the political and economic isolation that is Brexit, while ice caps thunder into rising seas. Summer is written thorough even the dissected bodies of swifts and in their song.[23] It is the hope underlying any winter’s tale.[24] It’s the real hope in the acknowledgement that every light has its darkness but it also has meaning, it ‘means something’.

And summer’s surely all about an imagined end. We head for it instinctually like it must mean something. … We’re always looking for the full open leaf, the open warmth, ….[25]

The most impressive rewriting of Summer comes from a passage that reads to me as if it brought together in dialogue the hope that might lie in religion and psychoanalysis, both robbed of their literal versions. Here summer is the beam supporting a church and even though we do, as we’ve seen even in novels we write about it, ‘overload summer … with our expectations of it’, we also know: ‘summers can take it. That’s why they’re called summers’.[26]

[1] Smith (2020: 289)

[2] ‘Winter’s Tale Summer 89’ is oxymoronic in that it juxtaposes a reference to the season Winter in abstract with one specific instance of a particular Summer, and its political and personal associations for Grace. Ibid: 24, 276ff.

[3] ibid: 3ff.

[4] ibid: 279

[5] ibid: 276

[6] ibid: 276

[7] Smith, A. (2020b:9) ‘For all seasons’ in The Guardian (Weekend Arts Booklet) Saturday August 1st 2020. Also available: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2020/aug/01/before-brexit-grenfell-covid-19-ali-smith-on-writing-four-novels-in-four-years

[8] I have often thought that Autumn gently satirises Byatt’s The Virgin in the Garden, both being about Elizabeth, an ‘old queen’ in the wake of a new one, Elizabeth II. Elizabeth in the novel refers, to her daughter’s great displeasure, to Daniel Gluck, an old anti-fascist German internee who appears again in that role in Summer, as an ‘old queen’ in the first novel with quite another reference.

[9] Smith 2020: 10 for the list of what are all ‘real’ internet sources.

[10] ibid: 9f.

[11] See note 7 above.

[12] ibid: 199f.

[13] ibid: 200f.

[14] ibid: 263

[15] ibid: 10

[16] See these references for instance: ibid: 7, 97, 187f., 276.

[17] ibid: 5

[18] ibid: 4

[19] ibid: 5

[20] See, for instance, ibid: 125, 255ff., 263f. For a brief critical account of her see Boettcher, S. (2018) ;Lorenza Mazzetti: Free’ in Luma Vol 4 (13) Summer 2018 Available at: : https://lumaquarterly.com/issues/volume-four/013-summer/lorenza-mazzetti-free/

[21] Smith 2020: 195

[22] ibid: 47f.

[23] ibid: 119

[24] ibid: 300

[25] ibid: 289

[26] ibid: 296

One thought on ““… Summers can take it. That’s why they’re called summers.”’ Reflecting on Ali Smith’s (2020) ‘Summer’ London, Hamish Hamilton”