The ‘literary event’ and David Mitchell’s (2020) Utopia Avenue London, Sceptre Books, Hodder & Stoughton

On the 14th July 2020, on the day of publication of Utopia Avenue , David Mitchell appeared with Claire Armistead, the latter moderating on behalf of The Guardian, in an online literary launch under the then Covid-19 conditions. David Mitchell described the title of Utopia Avenue as an oxymoron, with something like the following explanation. If Utopia is ‘no place’ it therefore describes something other than a world we know, whilst an ‘avenue’, even when used metaphorically, is very much a kind of place that describes one bounded thoroughfare or route between one state and another. So together as a term, ‘Utopia Avenue’ binds, Mitchell argued, the otherworldly possibilities of nowhere that can be physically known to us with a world of thoroughfares made real and physically locatable, things that have, as he said, ‘a postcode’. From there it was not a long leap, within this session at least, for Mitchell to describe the whole novel as an ‘oxymoron rich rabbit hole’.

I think we can play some more with this chosen description. A ‘rabbit hole’ is a term defined in an online slang dictionary as a means of transport to another world, the obvious reference point being Lewis Carroll’s fantasy of the way a young girl, Alice, accesses her Wonderland. In its more recent history it has also been associated to any experience that is over-extended and, at the same time, troubling, disturbing and/or psychedelic. It could also describe a pathway to a domains outside normal experience, sometimes by using means like drugs. Utopia Avenue has many such rabbit holes including voluntarily adopted addictive activities, substances, behaviours or involuntary psychiatric conditions. The deepest rabbit holes are those inhabited by Jasper de Zoet and at some points those involuntary states of mind are called schizophrenia. However schizophrenia is not the only way in which Zoet’s inner consciousness is described.

Other ways include notions of magic, horology and a compendium of links to Mitchell’s earlier novels and characters who recur between them. Jonathan Russell Clark has called Mitchell’s oeuvre up to Slade House (2015), ‘one gigantic story’ that involves a growing revision of plots and characters; characters such as Dr Marinus in The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet (2007) and The Bone Clocks (2014) as well as Slade House.[1] However my chosen dictionary definition suggest another way of interpreting the term:

Kathryn Schulz observed for The New Yorker in 2015, rabbit hole has further evolved in the information age: “These days…when we say that we fell down the rabbit hole, we seldom mean that we wound up somewhere psychedelically strange. We mean that we got interested in something to the point of distraction—usually by accident, and usually to a degree that the subject in question might not seem to merit”.[2]

I think this observation a rich one in approaching why Mitchell should calls his novel an ‘oxymoron rich rabbit hole’. It points to his fascination to what gives extended treatments, as in most Mitchell novels, of any subject that might be off the beaten track, ‘merit’ rather than them being merely a ‘distraction’ from what matters in history. For Mitchell, the subject is the peculiar ‘window in history’ that he named in this interview as bounded between 1967 and the early 1970s.[3] And what makes this period important was how music attained ’merit’ (from ‘three star acts’ you get ‘five-star songs’ is how Mitchel put it) because of the that time-period itself. It is a phenomenon called inside the novel ‘scenius’ (although I fear I can’t refind the page reference for that concept’s appearance in the novel) wherein individual or even group ‘genius’ cannot be such without the ‘scenius’ which facilitates such ‘genius’. It is a ‘electrical, revolutionary, experimental time’, where:

if you want it badly enough you can wish – [pause] – you can will – a different sort of society into being.[4]

The genius of these single characters and of the short period in which they are a group, works together with the scenius that enabled the production of albums. That new genre, Mitchell insisted, reshaped musical narratives and the moments that are the songs therein. Moreover these re-shapings have a political (that includes ‘the personal’) significance for characters who are examples of working class men, the ‘mad’, creative women and gay men, (such as the manager Levon ) and the most marginalised of all, ‘drummers’. Now, as with the period of time itself, which includes the Vietnam marches in London and the USA, May 1968 in Paris, no enduring political significance emerges as an outcome, ‘end’ or purpose of the novel. All that remains is the sense that we must maintain the oxymoronal state that is, on one side, seeking a better society with, on the other, the sense we have of the world in which we live in ‘avenues’.

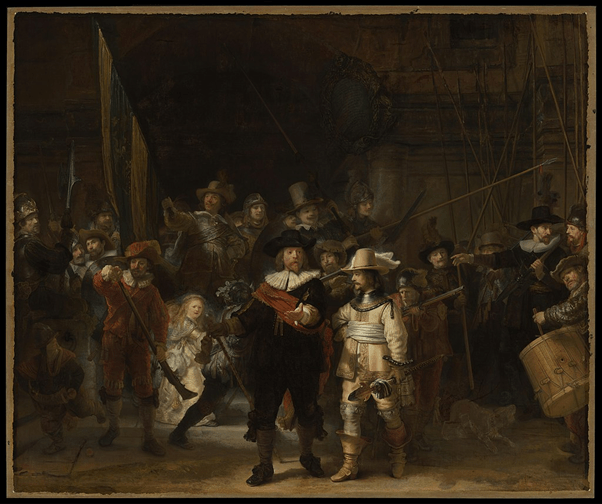

It is a novel that I found I couldn’t put down, even in the difficult to orientate within world down the rabbit hole of Jasper de Zoet’s schizophrenia or whatever his disturbances of perception and cognition are in the novel. It is a novel where influences come and go, making play for significance that is difficult to pin down, such as the working into a de Zoet lyric the sight of Rembrandt’s picture of a moment of historical insecurity in a Great capital in The Night Watch. In the chapter ‘Nightwatchman’, this magical realist passage might or might not record the unusual beliefs and perceptions of what we could, if we wanted, call ‘schizophrenia’ but it also presumes a role for the artist in thinking through social change:

… Jasper pauses at the corner of Amstelveld and holds up his thumb to test the half-moon’s blade. It’s comfortable being an Amsterdammer again. The English distrust duality. They equate it with potential treachery. In the Netherlands, having a German, French, Belgian or Danish parent is no big deal. The city’s bells begin their midnight round. Iron boom by bronze chime, stroke by stroke, the proud houses and the churches fade away. The conservatory and the poky room above the bakery in Raamstrat, where Jasper lodged for three years, vanish. Going, going, gone are the squalid brothels, shipping offices and scruffy cafés; the venerable hotels, fusy restaurants and concert halls; the Paradiso, the Rijksmuseum and the ARPO studios; Dam Square, the shuttered-up shops and the Anne Frank House; maternity wards and cemeteries; Vondelpark, its lake and chestnuts, lindens and birches, not yet in leaf; the city’s sleepers and the city’s insomniacs; even the bells in their towers that weave the impossible vanishing act melt out of reality until all that remains of Amsterdam’s ancient future is a brackish marsh, swept by gales, home only to eeels and gulls, hut dwellers with leaky boats and hungry dogs …[5]

Such passages of melting lyrical beauty and the dissolution of all orders in history to something more basic, including the orders of conventional grammar, are unusual in the novel. They largely appear up to the cusp of de Zoet’s redemption in the novel in the chapters based on his songs (the chapters are imagined as songs from the specific sides of the LP albums this fictitious band record). Other writers are as transparent as the characters themselves unless they go into the rabbit holes of drugs, love, need or grief. But the passage works as others to show that no political order, or its architecture, endures forever and that death, life and even records of mass extermination (Anne Frank) are as one to the possibilities of change that could be wished – could be willed – if we wanted it enough. In one of the lyrics Mitchell writes for his characters (such lyrics characterise each chapter) ‘Nightwatchman’ ends with:

I am the lone night watchman

This is my night watch.[6]

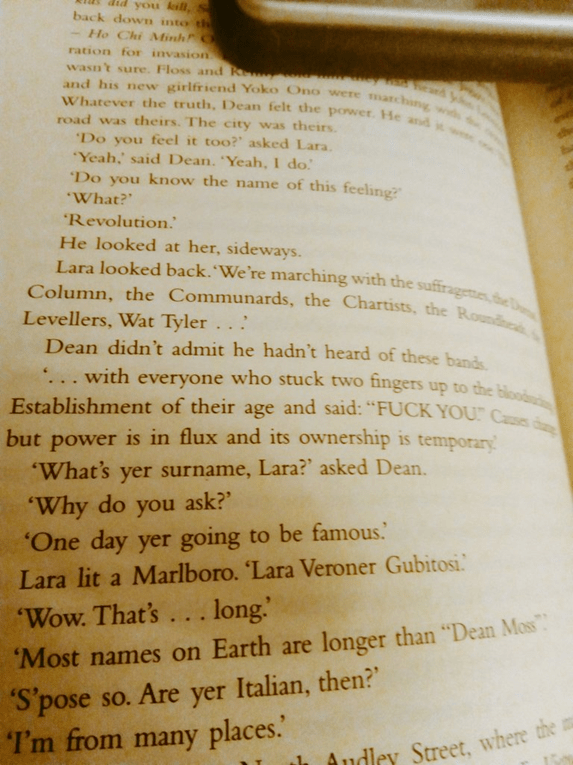

If you like a good accessible story, the prose does not utilise abstraction like that above in the main. Its main character, Dean, has limited knowledge but a great heart and his story therefore continually plays ironic jokes on his limited political consciousness:

This page (again the reference is lost) is important because Dean is shown to know no significant political history – only the Communards’ was also a band (yet to be) for instance – but Lara thought she was talking to Dean about episodes of left-wing assertion, however ill-enduring. The line, “Dean didn’t admit he hadn’t heard of these bands”, is just pure fun. But Lara’s statement that ‘power is in flux and its ownership is temporary’, is tremendously important to this novel.[7]

But his final song shows how scenius lifts him to political genius, even if by, again, the ironic means of ‘getting it wrong’:

If you were there in Grosvenor Square

where Anarchy killed Tyranny –

Dean realises his mistake immediately: it’s ‘Tyranny killed Anarchy’. Anarchy killed Tyranny means the good guys won. Maybe no one will notice, he tells himself, or maybe everyone noticed. …[8]

Mitchell uses italics here to note that these words are a thought not a speech but here this convention of his own is working hard. The novelist is allowing even Dean to become a focus of political genius, fused by the political culture itself where anarchic political movements at least modified how Tyranny operated, whether that be the tyrannies of contemporary American imperialism or De Gaulle in the Paris of 1968, who features elsewhere in the novel.

I don’t want to develop an argument here though – just show how wonderful and beautifully various this novel is. It should have been on the Booker list. It should …

Steve

[1] Clark, J.R. (2015) ‘The Ever-Expanding World of David Mitchell: One Novel Out of Many, Filled With Eternally Recurring Characters’ in Lit Hub Available at: https://lithub.com/the-ever-expanding-world-of-david-mitchell/

[2] Dictionary.com (2020) ‘rabbit hole’ in Slang Dictionary, Dictionary.com Available at: https://www.dictionary.com/e/slang/rabbit-hole/

[3] David Mitchell cited from Mitchell, D. & Armistead, C. (2020) In conversation with David Mitchell on You-Tube. Available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vxSlvxTfXBc

[4] ibid.

[5] Michell (2020: 293)

[6] ibid: 299

[7] See tweet at https://twitter.com/steve_bamlett/status/1287707706443345921/photo/1

[8] ibid: 501

“– only the Communards’ was also a band (yet to be) for instance”

Durutti Column were another band to be, on Factory Records in the 80s (home of New Order) whilst The Levelers were a 90s indie act.

LikeLike

Thanks Kieran

LikeLike