PLEASE NOTE: This review contains spoilers. If you haven’t read the novel, and prefer discovering how the narrative unfolds for yourself, don’t read it.

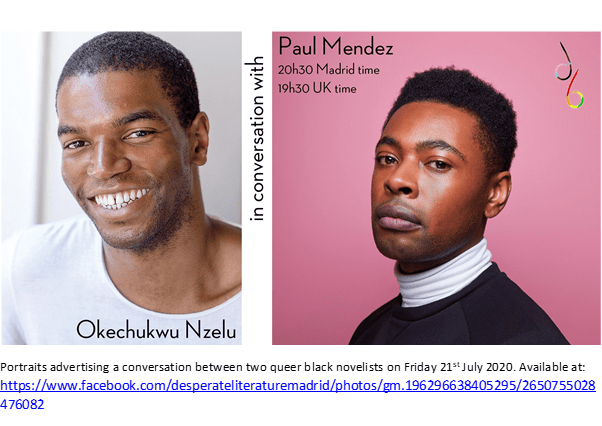

‘I’d be like your girlfriend, or summat. I’d look after ya’.[1] Exploring what intersectional identity might mean in the queer novel. Paul Mendez’s (2020) Rainbow Milk London, Dialogue Books.

Intersectional identity theory insists that social identity is only properly addressed when the multiplicity of markers which are mobilised to speak out one’s identity are considered. These markers include being identified as of black, white or brown skin colouration, race, gender, culture or religion, class, sexual orientation or position on the cis/trans continuum, variations of body ability, or mental state. They are not only not only multiple but can be sometimes experienced in differing configurations with each other that might differ too on the basis of whether that configuration is conceptualised by the person identifying or the person identified. Moreover, these configurations are not necessarily harmonious in their composition and different subject positions may conflict and / or co-operate with each other according to variations of place, circumstance or time. I would give examples but a better option is to ask you to read this novel – which by no means requires the abstract approach to identity I start with – but which can feel like the experience of so much conflict in the means by which one person learns diverse identities, empowering all or one selectively at different times.

Sometimes persons collude with the disappearance or disempowerment of some of those markers of identity. At other times, the perceiver themselves is unable to ‘configure’ the relation of marker signal and performance of role for which it could be the sign in a specific setting offered to them to read. As an example of this see Jesse as a Jehovah’s Witness attempting to read the signs and what they mean in the home of Carl and Abdul:

They lived together in that house as a couple. Two men. They ran a window-cleaning business together and had finished for the day. Various sexual configurations went through Jesse’s mind. They were both masculine; he thought he might be able to understand it better if one of them was a girl, but these two – men – lived together. They seemed so free.[2] (author’s italics)

Likewise the instance I cite in the title relates to young Jesse, the main character of the novel, who is trying to explain what his relationship might be to Fraser, his friend, were they to share a flat together. It can only be expressed in the state of both Jesse’s consciousness and Fraser’s receptive powers, as Jesse guesses them to be (even after meeting Carl and Abdul), by proposing a transitional status in Jesse’s gender role vis-à-vis Fraser’s assumed stasis in the masculine role. This is one of the many tender moments wherein Jesse proposes to a man a more permanent status in a relationship only to be cast off by the other’s choice of ways symbolic reaction, such as exiting the scenario. Thus he proposes a more enduring relationship with the first man he has had any sort of sexual relationship, in a railway toilet, only to be made conscious that identity markers not only conflict but establish, in some circumstances, hierarchies of status between them:

“Can I ‘ave ya number?” Jesse whispered, shuffling up from a crouching position, …

“Nah, mate,” the man said, and showed Jesse his wedding ring. With that, he kissed him on the mouth, … and disappeared right out of the toilets without washing his hands.[3]

Here, markers of masculinity include details like the appellation, ‘mate’ and behaviours such as leaving a urinal ‘without washing his hands’ (will that sign of stereotypical masculinity be readable after Covid-19?). These signs mix uneasily with others like the kiss directly on the mouth. For intersectionality is not only about the range of identity markers but about how you interpret and use such markers in an enactment of the roles in which they are the properties, settings and costumes. For markers, such as a ‘wedding ring’ can indicate the role (which here and at the date of setting means married heterosexual identity) but not how it is played. This is true of many identity markers, such as words attributed to skin colour and the roles they are supposed to point towards. For all identity markers are mediated by how the roles are conceived, by whom and for what purpose – for scripting actions or interpreting those scripted actions from another subject-position. Jesse’s sensitivities to being ejected (‘disfellowshipped’) from his Jehovah’s Witness community are read as too distant from the hard masculinity associated with being black by his work teammates at a McDonald’s restaurant:

His teammates circled him, challenging him to become harder, more aggressive, their idea of black. … They were mostly white and Asian boys who acted like black boys. He tried to change his accent so that he sounded more black. One of his colleagues joked that Jesse was like a black boy trying to be a white boy trying to be a black boy. …[4]

As the novel progresses we will see ‘accent’ become a further means of further refining the sectional-identity markers out of which complex identities form, even down to differences indicative not only the sound imagined to be that of black men in the quotation above, and in the mimetic 1960’s Jamaican accent of the first section of the novel, but class and English regional affiliation in 2020 multicultural England.

Jesse as a sex-worker in London encounters a whole range of people, where identity markers are to be read complexly if we are to understand the nature of these relationships, not least in his white partner-to-be, Owen. A key figure is his customer Thurston, who appears early in the novel, out of the linear sequence of the time of the narrative. It is his role to safeguard Jesse’s sexual health, thus helping to ensure his survival through the AIDS years. He appears again near the end of the novel, where he also plays a vital, if hardly self-conscious, role in informing the hidden family relationships uncovered by the novel.

In both points of meeting Jesse and Thurston cover some of the same ground in making the story of their encounter significant. Both occasions focus on the likeness of Thurston to Jesse despite their opposing sexual preference markers as gay men. Such markers are the very traits emphasised by participants who seek rendezvous with compatible others on Gaydar, a gay male dating site. Profiles on this database serve to match trait to trait people looking for another gay man on the basis either of a desired likeness or of desired difference . Let’s look at the descriptions side by side:

| Thurston as met on Gaydar in ibid: 56 | Meeting both again, but in Jesse’s perspective, recalling what they knew of each other in ibid: 308f. |

| Jesse had wanted to close the deal straight away but Thurston slowed him down with his respectful tone. He was looking for someone to get to know and see for some periodic, safe and sensual attention. He was fifty-one, tall, slim and passive. His pictures were all of him smiling, with paintings behind him in a gallery, or in a fancy restaurant or bar, where someone else had been cropped out. They found they were both born in the Black Country, Thurston in the semi-rural village of Tettenhall, outside Wolverhampton; Jesse in the industrial village of Wordsley, outside Dudley. | They reminded each other that they born in the Black Country – Jesse in Wordsley, a village near Dudley, Thurston just down the road in Wolverhampton – which amused Jesse. Thurston was too elevated and grand; … Thurston stressed its first syllable, like a Pathé newsreader: WULL-verhampton, while most people from there say WULL-VRAMpton, slightly rolling the r. Thurston told Jesse he was the son of a rector, who’d grown up in Tettenhall (Tetten-hall; TETT-null), a historic village in what was then Enoch Powell’s constituency, attending the private school there; … Thurston, growing up five miles away in a pretty village where everyone was white, saw little of the racism Jesse’s mother’s generation had to endure, though everyone his parents knew sided with Powell. |

There is a conscious recall of the prior passage by the later one. It is marked by the near similarity of chosen descriptors of the places named Wordsley and Tettenhall. However, the difference between the passages play new games with a reader around this original difference, intersecting it with further differences created from sectional-identity markers. In the second passage the apparent names of those villages have a kind of innocence and sameness in both being no more than two relatively places of little distance from each other in ‘The Black Country’. In the second passage, it is emphasised that each person in this interaction understand different things even by these place-names that tell us about them and the societies they understand to be their norm. This is not just because we know that how you sound these names itself is a marker of differences of class.

That difference is indeed one indicative of the class of the speaker but it is also associated with the racial characteristics of the areas and to the patterns by which racism reproduced itself in these different classes. The play around the significance of Enoch Powell to each area is very skilfully built into these expansive passages about the two of otherwise multiple intersectional and conflicting differences focused upon here. The placing of class in the sectional-identity marker that is accent is just one of the many signs Jesse has learned to read in order to differentiate people in the duration between these passages. Mendez even gives us a moment in this learning in Jesse’s initiation to the life of Owen, as he reflects cognitively and in his feelings on his difference from that man:

Jesse … was slightly resentful of Owen’s encyclopaedic knowledge of things, though felt another wave of infatuation at the mention of partner for life. He hoped one day to be the sort of person who could confidently answer any question thrown at him, but suspected that the versatility of Owen’s mind was a result of its Cambridge education. Even the word sounded smug. If it was in the Black Country it would be called Cam-bridge, with a hard a, not Came-bridge.

It is the power differences based in class, English region and educational status that conflict to make one resentful, the other smug, at least in Jesse’s mind and which will be used to belittle him again later in the words of Lady Pamela Groombridge, the wife of one of his once customers for closeted and costly sex.[5] These are differences that he will also apply to Thurston, who, at the least comes from the same region. My point here is that the prose of this novel relishes intersectional differences. It raises them of them separately at points and, to some extent validates them separately, but at the same time shows that intersectionality may invalidate hanging the meaning of even one person’s life on such a single difference.

This is even the case I’d guess in the single difference which animates much of the novel, that of race and its analogies with skin colour. For instance, the symbolic highpoint of this novel is the discovery of Jesse’s father in a self-portrait he first saw in Thurston’s ‘fancy’ home with its many paintings. He discovers that ‘spitting image’ of himself in that portrait’s black nude of which he had been previously warned. [6]Before knowing of this father – who is born in Section 1 of the novel in the 1960s – the portrait seen on his first rendezvous with Thurston, who owned it, but which he haunted before this more specific identification through his acquaintance with painted images of ‘Christ on the cross’.[7] That nude has the same skin, and the same large penis and the same sectional ambivalence between male and female, strength and vulnerability: ‘The nude’s dick lay thick across his groin, almost purple; his body in soft focus, a black male Ophelia’.[8] And despite the prominence in this moment of discovery of a production of Othello, the only Othello to match Ophelia’s passivity in Nude with Othello is the hybrid rose of that name bred by a white man.

And that red rose signifies blood, suffering and mutilated bodies – the image his father had used to show the progress of his progression through AIDS’ attack on his body in these early cruel days of the virus’ conquest of people. This could have been an image of an achieved black identity but it is not, not at least without taking into account his father’s bisexuality and martyrdom to AIDS, because his newly discovered black family have the ultimate understanding of intersectional identity paradigms. As Glorie says of the picture of Owen, the white man Jesse will marry (wherein even the historically situated circumstances of his mother are understood by both): ‘“With what’s going on in the world, it’s best to be with someone who makes you feel loved. Nuh waste your time with people who don’t”’.[9]

But my focus on the queer aspects of this novel needs to take into account the way that intersectionality impacts on the process of growing up queer. And the aspects recognisable from this novel are twofold and depend on the fact that performing love and sex to a man is anyway a fractured reality, intersectional by virtue of each of its often warring parts, even at its best. Nadifa Mohammed in a fine review in The New Statesman picks out from the novel a ‘stretch in the middle where the prose is fine, fluid and luminous’. That piece describes Jesse’s discovery of a possible intimate love for a white academic poet, Owen, at this point, an unknown flatmate. Of that love, she says admiringly, and as if in explanation of the strength of the prose therein: ‘Here both Jesse and Mendez’s sinews seem to relax and you can see how, once the sexualised power-play has diminished, there can be real intimacy between men, ….’.[10]

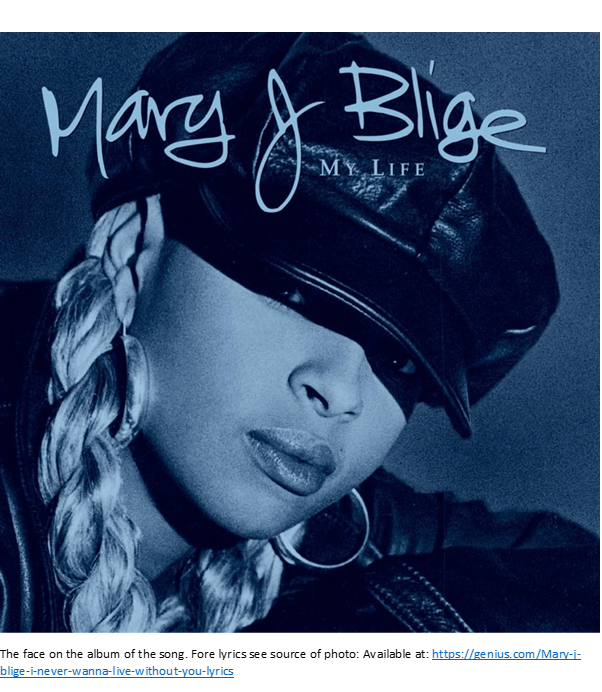

That this novel is semi-autobiographical is without doubt but here I think Mohammed gives too much weight to the connection between Paul and Jesse, and to some extent misreads the prose and the recording of gay male experience it holds. It is an intimate ‘stretch’ but it is as dependent on foreclosure of its intimacy as even the less ‘romantic’ sections describing types of male rendezvous. After all once Jesse falls asleep in a romantic dream extended from hearing Mary Blige’s ‘I Never Want to Live Without You’ whilst clinched by Owen and being fed a spliff, Owen drunkenly finds another sexual outlet across London and drives in an inebriated state towards that second-best bed to his fate in a car accident. In contrast to Mohammed, a fine novelist herself, I’d say this ‘stretch’ displays at its finest how Mendez’s prose modifies the intimate dreams of ‘married’ male-to-male union by exquisite ironies derived from the intersectionality of all relationship making and the power embedded in all relationships.

Identification of male desire with that of classic female performances of love for a man in pop and other musical cultures runs throughout the novel – not least in the older stocky gay man Rufus’ statement, delivered from, ‘perfectly fluffed-up pink and green damask cushions’, and italicised in the original text: ‘Inside every gay man is a fabulous black woman’.[11] This theme is at its height in this lovely scene but shoots it through with a kind of irony wherein a model of female desire is co-opted to romanticise submission to male will. If anything what the ‘stretch’ signifies in its prose is precisely power-bound relationships in which male identifications with women carry another power relationship over into the space occupied by two men performing their love for each other and, in which the entitled white gay male cuts up that borrowed female role as they do it in the name of his own pleasure.

An escalating blaze of strings and brass immediately retreated to a whimpering guitar phrase like a pining dog’s, over which Mary pleaded. Owen sat down and chopped lines again on her face, while Jesse sang along, every word, in his low tone, unintentionally performing for Owen, who sat quietly, watched and listened, smoking the spliff.[12]

Thus, whilst I agree there is exceptionally fine and luminous prose here in this middle passage, it is more nuanced with power and almost subliminally violent potential in the depiction of ‘intimacy’ than Mohammed’s representation of it allows. Intimacy as a concept is as locked in how the sectional roles with which we perform our identity articulate power and differences of power. Of course Owen is merely said to be ‘chopping’ lines of coke on the face portrayed on Mary J. Bilge’s album (as pictured above) but the words chosen perform repressed violence underlying the prose. For, in these sentences, the pursuit of the love of the white man becomes a power by Owen transforms of Jesse into the black woman who ‘performs’ for the white man.

Hence I think there is a kind of misunderstanding of the relationship between intimacy, race and gender in Mohammed’s reading of this novel and, in this particularly detailed treatment of ‘being loved by a white man’.[13] Owen is a truly interesting character in this novel but, in my reading, I do not think he escapes analytic distance nor is his destiny as Jesse’s husband, a mitigation of the fact that he like other white men represents the operation of complexly structured privilege, including the privilege of being cast as romantic hero. For Owen, in this section, is no more than the product of Jesse’s romantic fantasy, the equivalent of those in Mary Blige’s lyrics.

Jesse’s point of view is after all constantly unreliable, constantly creating romantic potential about the most unlikely of white men: whether it be the unknown quantity that is young Fraser, a bisexual office-worker in a toilet whose sexual organs were ‘intimidating, urinous and pungent’, the sentimental loser Rufus or any others.[14] I love the passage in the section pointed to by Mohammed where Jesse, lying back on Owen’s thigh, wishes, ‘he had saved himself for this moment, that he had never been touched by a man in his life’. He goes on to list those men in a near breathless 26-line sentence, which reads like one of the lists in a poem by Whitman but with more comic effect. Some of these multiple experiences we know of as reader, others we don’t. How they act is to deflect the reader from being swept up with Jesse’s ability to say all that rich human experience ‘didn’t matter now’.[15] After more projective romancing of the story of his current contact with Owen that would ‘make sure Owen never needed anyone else’, he easily slips into another concern:

Besides, what if Owen was just another bad man waiting to reveal his true self as soon as he’d taken from him the sex he wanted? What if he was another Rufus? Were all the men the same? Jehovah destroyed Sodom and Gomorrah because the men wanted to fuck the angels he sent. …[16]

This is a prose whose skill in ironic comedy is its real strength. Jesse’s vision of intimacy is smashed within pages as Owen heads for more timely sex, despite his own lethal inebriation, with any man he can find who has not fallen romantically asleep as Jesse has. When we see Owen again (rather a broken (in a car crash) romantic hero like Jane Eyre’s Rochester), it is with the knowledge that the marriage will not be a romantic dream but a realistic exchange in which the knowledge of the commonality of men – they are not ‘all the same’ but they are all men – is fused with other sectional identity markers that make Owen what he was, is and will be. Jesse, for instance, will be the force that turns Owen into a poet who can explore the queer voice.

And the later Owen will be acknowledged as, in some ways, a product of the way desire has been moulded for black men in a racist society. This seems to be the main function in the novel of the meeting between the affianced Jesse and Owen with Owen’s (white) publisher from Endymion Press, Nick, and his black male partner, Jean-Alain. Jesse, even in Owen’s presence recognises Jean-Alain’s, ‘glowering sexual presence that makes Jesse glad for his black privilege, in that he cannot be seen to blush’.[17]

That reference to ‘black privilege’ is won against his discovery that there is nothing personal about ‘white privilege’. Both Nick and Owen (and Thurston and etc.….) are white, they bear the advantage of white privilege. In this section Jesse learns that this will not go away but it can yield some advantages to him of not expecting white men to be other than white men. This is a redemptive perception – of a truth that need not hide the fact that a white man may still be a reasonable choice of married partner to Jesse, with some openness to otherness that such realistic wokeness as a black person and gay man marriage might bring. I do not doubt that both Mendez and Jesse still validate the following perception of Jean-Alain, whom we learn here has also been a past lover of Owen’s:

… I just couldn’t deal with what I was feeding into my brain, the dichotomy of wokeness and the attraction to lick, suck and fuck white ass or worse still dreaming of licking the oppressor’s ass at the very same time as being fed the truth about the long history of his terrorism.[18]

And this redeems, to some extent, other white men in the novel, even the drug-addled and needy ‘Dave’, who can only work to male good or ill changes in the power awarded to them by the beliefs and privileges enshrined in sectional-identity markers.

This perception is also true of the writer, who may hope to make art about their pure identity but will inevitably have to compromise with complex realities even in the identity of black writers and artists such as those listed by Jean-Alain: ‘Franz Fanon, the non-fiction of James Baldwin, CLR James, Audre Lorde. etc, etc. 12 Years A Slave …’.[19]

… if I blame individual men for all that, I can’t live. … I actually came to the conclusion that I was never going to speak to a white man again as long as I lived, …. But how can that be? If I write a book, who’s gonna buy it? White people. ….[20]

Jean-Alain speaks those truths, including the revelation of Owen’s past with him. Jesse listens and learns. The end of this novel then is not that of a romantic novel unless the cynical knowledge of doing what is possible within complex power-situations in great novelists like Charlotte Brontë, George Eliot and Jane Austen are included in that genre.

For me this novel is good, and perhaps better in my view than in Nadifa Mohammed’s, because it is a strong representation of what it means to say that our apprehension of identity and identity politics cannot rest on over-simplistic categories, over-simplistically interpreted with unchanging attributes, like gay (even queer), men, black and white, disabled and enabled and so on. There is so much more that I love about it but here I rest.

Do read it!

Steve

[1] Mendez (2020: 83)

[2] ibid: 68

[3] ibid: 109

[4] ibid: 101f.

[5] See ibid: 341

[6] ibid: 296f.

[7] ibid: 306

[8] ibid: 312

[9] ibid: 348

[10] Mohammed, N. (2020) ‘Paul Mendez’s Rainbow Milk: A bold and raw novel’ In The New Statesman (1 July 2020). Available at: https://www.newstatesman.com/culture/books/2020/07/paul-mendez-s-rainbow-milk-bold-and-raw-novel

[11] ibid: 130

[12] ibid: 243

[13] ibid.

[14] ibid: 108

[15] The whole sentence nearly fills the page, ibid: 244f.

[16] ibid: 245

[17] ibid: 322

[18] ibid: 330

[19] ibid

[20] ibid: 331