NOTE TO SELF: I’ve got this as far as I can and I doubt I’ll revise. Yet I do sense lots of problems remaining in my own prose. Still it is enough for what I want – to write out how this book seemed to me to work for my own understanding. If anyone else finds it worthwhile, I’m pleased to share. If anyone starts and gets ‘fed up’ I’m with them there too. Steve.

‘”Queerness”, José Esteban Muñoz wrote, “ has an especially vexed relationship to evidence”’.[1] Reflecting on why Mark Doty, a queer poet, insists on the queerness of the body of Walt Whitman’s verse in his reflection on the elder poet’s influence on queer poets, America and himself (Doty, M. (2020) What is the Grass: Walt Whitman in My Life London, Jonathan Cape).

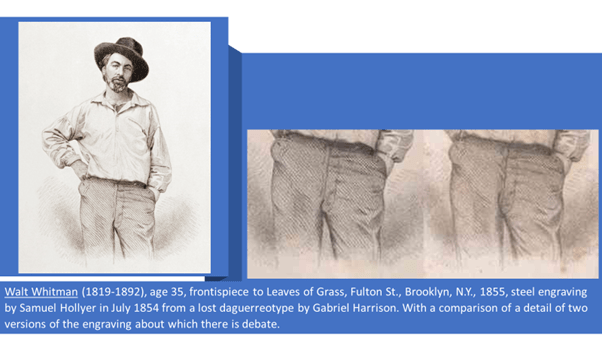

Amongst the many ways that the minutiae of self-representation by poets have been examined, the oddest is the debate raised by Ted Genoways and popularised by Ed Folsom of the Walt Whitman archive. It’s based on the evidence of the engraved portrait for the 1st edition of Leaves of Grass on the left below. There are two states of the portrait because of the volumes revision between 1855 and 1856. The debate centres on the contrasting detail from the two shown on the right.

Folsom writes thus:

“Ted Genoways has recently discovered some intriguing variations in the frontispiece engraving, suggesting that Whitman may have worked with the engraver to enhance the bulge of the crotch in the figure, thus giving visual support for Whitman’s introduction of his name halfway through the first long poem (later titled “Song of Myself”): “I [. . . ] make short account of neuters and geldings, and favour men and women fully equipped, / And beat the gong of revolt, and stop with fugitives and them that plot and conspire. / Walt Whitman, an American, one of the roughs, a kosmos, / Disorderly fleshy and sensual . . . . eating drinking and breeding.” The bulging-crotch version of the engraving appears in all of the copies in the first binding (fig. 5b), but many of the copies in the second binding contain the earlier flat-crotch image (fig. 5a), which was printed using the more expensive chine collé method of printing the image on a thin sheet of India paper and gluing that paper to the page at the moment of impression”.[2]

Doty references this debate in discussing Whitman’s attempt to brand his product: ‘positioning himself for his public, shaping the way he’d be viewed’.[3] In doing so, Doty also rejects Folsom’s argument that Whitman chose a more modest branding for the second version (5a). That the second version was more modest, of course, does not in itself necessitate that this was by Whitman’s informed choice. Doty attempts to evidence his view of Whitman over Folsom’s that his informed choice was the opposite of that stated by Folsom by quoting Fanny Fern’s 1856 review of the novel and its reference to ‘ripe and swelling proportions’. However, the quotation seems not to support that view at all, in that the display of the ripe and swelling is used by Fern to characterise exactly what Whitman was not doing, not what he does. In as far then that Doty seeks academic evidence for his view, I think he fails (in this instance at least).

But I reference this debate to argue that Doty’s arguments about Whitman don’t rely on such evidence, even when he attempts it. In this case he claims honestly that his conclusion that Whitman would have ‘chosen to reveal more than less’ (which is the exact opposite meaning of his quotation from Fanny Fern) is based in the end on nothing more than his subjective impression: ‘My own sense of the Walt Whitman of 1855 …’.[4]

I would say that this is true of the book and its significance throughout. Its achievement, and in my eyes it’s a very great achievement, is to show what the process of reading poetry is: the processing of its words, micro and macro versions of its form (such as delineation at the micro level and the spatial-temporal structure of whole poems, section or volumes at the macro level) and what is ‘between the lines’ or in some ideational affective and cognitive space evoked by the poem.[5] This is clearest in the beautiful final paragraph of the book. His envoi performs the action of ‘silencing’, ‘stilling’ and ‘ceasing’ the work of the book as a whole:

where I … cease my fountain of appreciation and interpretation, and allow him to still my hand and my lips, and mark here my silence as his words accomplish what words cannot.[6]

The word ‘still’ denote the fate of embodied sound at the lips and bodily motion, including that of the writing hand – at least to the point of a ‘mark’ we cannot hear since noise is only a potential of marks when the marks are also words. The only evidence that will reveal Whitman to us, the book continually tells us, is in the liminal area between speech and words, on the one hand, and the unspoken, unsayable, unwritten and unwritable on the other.

Clearly reading and hearing great poetry must involve degrees of reading skill, some reaching into the space of the strictly unreadable: ‘The reader in me believes in words, the poet in what lies beyond them’.[7] Thus the following early passage from the book insists that queer male communities access quasi-spiritual spaces in the poem through the force of their desire and fill that emptiness with what they lack (Lacan lurks in this prose and appears from behind that veil sometimes).[9] That content is not necessarily erotic but a space for a wholeness of being. Writing of his own visit to the men’s changing room at ‘Crane Beach, north of Boston, …’, he says:

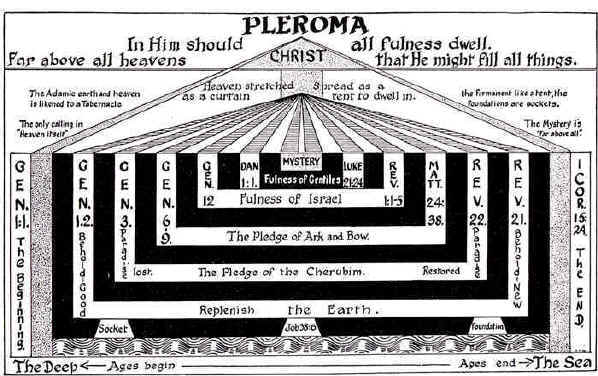

It feels like a box of pulsing, masculine life. Overwhelming physicality, so much of the flesh in one place it seems to be of the soul. Not erotic exactly, unless it is an aspect of eros to be made aware that you are a quantity of skin in a larger field of skin. as if a brushstroke in a painting might be made aware of itself as one of the uncountable strokes that comprise the whole. … The word I want to use here is pleroma, a Gnostic term for the fullness of all that is divine; …, a “space” that is not a space.[10]

There is an explanation in the invocation of Gnostic written traditions of the oft mystical yearning of Doty’s prose, as in Lacan too I’d say. But it also explains why Doty feels it appropriate to use his own biography and that of his lovers to explicate what lies behind the ‘words’ and spatial markings that make up a printed volume of Whitman’s continually expanded Leaves of Grass. And that includes too half-perceptions and hints about what is silent, or even erased by contradiction – sometimes by Whitman himself – in the poet’s biography. For Whitman said he was not erotically attracted to men when asked and his ‘lovers’ were often ‘airbrushed’, as in the painful correspondence between Walt and Fred Vaughan, once a ferryman.[11]

Even in what looks like conventional literary scholarship we see Doty leaning out from the whole queer community’s knowledge of each other and the historical oppression of their mutual desires in order to interpret words ‘between the lines’. The brilliant explanation, for instance, of the genesis of Bram Stoker’s supernatural villain, the vampire Dracula, from the character and poetry of Walt Whitman in chapter 12, ‘Insatiable’, depends on such a hermeneutic leap.

It starts with the evidence of a rather brief meeting between the authors and some supposition about the queer elements in Stoker’s Gothic novels (of which there are many in my view). It ends with a discussion of the poem from the Calamus poems in which redemptive blood, tears, and semen, ‘all ashamed and wet’ are equated and blur with the Gothic and vampire symbols it uses.[12] And, of course, the vampire analogy – positive in Whitman but negative in possible analogies like Poe and Stoker, also links to another reason for itself – that great poets are great because they are ‘undead’: living a liminal life in the words and spaces of what we mean by a life in poetry.

The examination of the poet’s knowledge of death is a lovely part of this book. It feeds off Doty’s intimate knowledge of loss during the AIDS crisis – and improves immeasurably in my view on his earlier ‘Biographia Literaria’ on that subject, Heaven’s Coast.[13] Yet I will not develop this argument precisely because of its magnitude. Suffice it to say that Doty makes the whole life and deaths of the queer community the basis of the literary greatness of Whitman in that community, and perhaps in that community (my community) alone.

In my title I quote Doty citing José Esteban Muñoz view of the ‘vexed relationship’ of ‘queerness’ to ‘evidence’.[14] This is a reflexive and prescient moment in Doty. In it he shows how ‘queerness’ establishes itself in time, both in its unspoken and unspeakable past and in projection towards futurity, by evidence that will be considered by most sciences as literally under the radar. And what is more he shows that the queer scholar or reader of poems achieves insight into the queer content of art only by contesting an ever-present homophobic censor within the products of homonormative cultural institutions. Examples of such might be academic or cultural press guardians in society, or internal to persons, their introjection into our psychological core beliefs, even those of the artist themselves. The role of this censor, external or internal, is to deny the existence of the queer past or past queer people:

there is often a gatekeeper, representing a straight present, who will labor to invalidate the historical fact of queer lives.[15]

So don’t look to critique this book on how it uses evidence from Fanny Fern, Bram Stoker or Fred Vaughan to establish its points about the true sources of Whitman’s greatness, as an academic book would. Rather look at how it reads the poems themselves as evidence for its deep characteristics such as its ‘queerness’. And this evidence is drawn from a truly expansive sense of the processes involved in ‘reading’. At least three types of activity are demonstrated in this book to show how apparently subjective ‘readings’ respond to text:

- The literary critical and expository technique often called ‘close reading’;

- ‘Reading between’ the lines and in the surrounding spaces; and,

- Reading through ‘felt understandings’ which unite the experience of a group of readers to the writer and to each other.

So let’s look at examples of all three, while still insisting that they do not exhaust the list of processes used.

Such readings have become a staple method of academic English studies since the 1920s In England, although they now are often contributed to by the interdisciplinary research method we call close textual analysis which is applied not only to literary text but graphic or plastic forms, including architectural works, considered as texts. Doty’s skills cover both traditions but his much more subjective judgements ensure it is more like the first. An example is of a stanza from Song of Myself in chapter 2 wherein Doty analyses the syntax, verbal semantics, and metaphors. Describing the whole stanza as ‘one of the most beautiful sentences in American poetry’, he looks at how that fact ensures that we read not only its words but their pace, authority, and temporal placing – with references too to its use of repetition in significant line locations. The associative contexts of both rare words and neologisms help these themes, including a reference to ‘the loveliest neologism’ in American English, Elderhand.[16]

Numerous textual extracts are read like this, many in even more skilled ways than you’ll find here.[17] But even here you will see that this stanza is read as no more important than the ‘silent white space’ that precedes the stanza, situated between it and the preceding stanza. This reading of ‘space’, wherein Doty intuits ‘tender sex’ between ‘You’ and ‘I’, brings us to our next kind of reading process.

- Reading the spaces in between words, lines, stanzas, and poems.

Introduced in chapter 8 most fully, it is clear throughout the book that even the most closely read words will not always unearth meanings that are buried as deeply as they are to frustrate that very purpose. Doty argues that sexuality is only ever inferred from poor, and often thin evidence from the past:

Unless someone still living can serve as reliable witness, our knowledge is inferential and provisional, supposition or an educated guess. Try to trace the histories of sexualities outside the mainstream and this is even more the case; queer sex leaves no marriage records or genealogies inscribed in family Bibles.[18]

Not only that but there are good reasons for hiding truths about those marginalised sexualities and / or denying them, as Whitman certainly did in any record likely to reach a reading public, despite open discussion of the possibility globally. The new public included visits from influential foreign adherents of his ‘adhesiveness’ doctrine who were ‘taste-makers’ in their own countries: in range from the hidden interests of Bram Stoker to the open demands of Edward Carpenter, John Addington Symonds and Oscar Wilde.[19]

Hence to read Whitman is to ‘read between the lines’ to find that which is unnamed (‘dare not speak its name’) or ‘mysteriously named’.[20] Doty also calls this thing living between words, lines and stanzas ‘unspeakability’ and he analyses that term.[21] One of the best examples of how ‘unspeakability’ thrives lies in the analyses of what seems to us now the very open homoeroticism of the Calamus poems in the 1860 edition of Leaves of Grass. As Doty elegantly puts it: ‘no one save men who shared the poet’s desires seemed to notice. … The subject of male same-sex desire remained firmly unseeable’.[22] The calamus plant itself is described by him as:

something wild and untamed – half savage

coarse things

Trickling Sap flows from the end of the manly tooth of delight[23]

The fluidity here is of the sexually active and engaged body yet this detail, even its ‘coarseness’ can, perhaps, only be understood by those who know the male body as the focus of desire. This is even more beautifully spoken by Doty where he examines Whitman’s invocation of bodily touching, wherein close reading of the multiplicity of meaning in words and the structural features of the dynamic flow of the verse and its sound quality (down to alliteration and assonance) in section 29 of Song of Myself become an enactment of queer sex:

this touch is blind, loving and wrestling all at once. … It’s simply not possible to conceptualize this touch in a logical way, yet the overall sense created by this collision of terms is unmistakable : an evocation of sexual activity that is loving and rough, combative and piercing.[24]

But Doty’s word ‘unmistakable’ here is playing games, because the truth is that most readers of his time did ‘mistake’ the poem. Some, even now in 2020, look to see only the veil of metaphor over some quality of abstract thought and feeling rather than its insistence that spirit includes body. This brings us to a final process of reading identified by Doty.

- Felt understandings that unite a group and make them whole or more whole.

Doty insists that the ‘felt understandings’ that complete the poems of Whitman in the reader’s mind are not those of the ‘troop of Whitman biographers and scholars … who will tell you Whitman was not queer’. Instead he insists that its ‘intent’ is to infuse ‘description’s of men’s bodies with such palpable longing’ that is really only knowable to ‘anyone sympathetic to such desires’.[25]

This extends even to understanding the poem’s ability to make its ‘God’ knowable through male sexual congress and amativeness. A thing which will be understood in a word such as ‘bulging’ to describe delights that are covered by towels in one beautiful section, wherein God’s presence may or may not be metaphor:

As God comes a loving bedfellow and sleeps at my side

all night and close on the peep of day,

And leaves for me baskets covered with white towels

bulging the house with their plenty ….[26]

Doty tells us, if we needed to know, that the condition of being a gay man has historically been that of someone who must read and disambiguate the world in order to maintain one’s safety and the integrity of one’s feeling by understanding a range of certain signs and codes. Words and spaces in poetry constitutes such codes of marks and space or speech and silence. This is the truth of Whitman’s ‘body of work’ which is ‘his only body now.’ That body qua re-imagined flesh one can touch and be touched by if and only if you queer the superficially accepted norms of the world:

Sexual life carries him beneath the social surfaces, reveals the flesh beneath the uniforms, and calls appearances into question, disrupting what’s assumed to be true.[27]

This book is wonderful because it insists that in asking us to read excerpts from Doty’s own life, his thoughts and feelings as a gay man and those of other gay men, gets us nearer to the meanings in Whitman’s work than either scholarship or diligence.

Doty even excludes his own researches into the ‘mystery of desire’ from giving any exclusive entry to these poems. That is because the poems fail just as much as desire does itself to tell us in words , ‘what is that compels us, what is that we want’?[28] In as much as the poems can tell you, it is because they move in the same direction towards understanding what constitutes fulfilment as do our own desires that have not been locked into objects (which bodies also can become of course) alone.

Connecting this to the body of the experience of all queer men and women is the role of another concept from Muñoz: ‘Queer Utopia’. This is not a matter of ‘rainbow-decked celebrations of pride’ or a pretence that there is NOW no difference in loving outside of norms but, ‘a horizon, configured in our desires, informing our actions and dreams, never exactly reached’.[29] But it is a communal dream like Whitman’s imagined city of male lovers of each other. Let’s assume then that some reading sets not the norms of a group but the feelings of a group who have so long been excluded from what are considered the norm for groups.

I can’t state this in my words. You need to read the book. An easy task if you’ve read this. It is pure joy.

Steve

[1] Doty (2020: 177)

[2] Ed Folsom (2005) ‘Whitman Making Books/Books Making Whitman: A Catalog and Commentary’ in The Walt Whitman Archive (online) The second comparative illustration above this quotation (on the right) contains Folsom’s figures 5(a) and 5(b) respectively in that order. Available at: https://whitmanarchive.org/criticism/current/anc.00150.html.

[3] Doty op.cit.: 191.

[4] ibid: 191f.

[5] ‘Reading between lines’ is a subtitle of a section of the discussion in the book; ibid:109.

[6] ibid: 276

[7] ibid. Beginning of last paragraph.

[8] Missing.

[9] He invokes Lacan by name in explaining Cavafy ibid: 164.

[10] ibid: 42

[11] ibid: 135ff.

[12] ibid: 168f.

[13] Doty, M. (1996) Heaven’s Coast: A Memoir London, Jonathan Cape. I see this book as one of the genre established by S. T. Coleridge’s Biographia Literaria.

[14] ibid: 177

[15] Muñoz cited ibid: 178

[16] ibid: 28f.

[17] Such as in the opening of the brilliant chapter 8, ‘Buds folded beneath speech’, ibid: 100ff. But this chapter is also the source of Doty’s definitions of what it is to ‘read, literally between the lines’. (ibid: 107)

[18] ibid: 88

[19] ibid: 110 for Carpenter, since the quotation is interesting

[20] ibid: 107

[21] ibid 109

[22] ibid: 126

[23] cited ibid: 125

[24] ibid: 102

[25] ibid: 177

[26] cited ibid: 178

[27] ibid: 91

[28] ibid: 81

[29] ibid: 145

3 thoughts on “‘”Queerness has an especially vexed relationship to evidence”’. Reflecting on why Mark Doty, a queer poet, insists on the queerness of the body of Walt Whitman’s verse in his reflection on the poet’s influence. (Doty, M. (2020) ‘What is the Grass: Walt Whitman in My Life’”