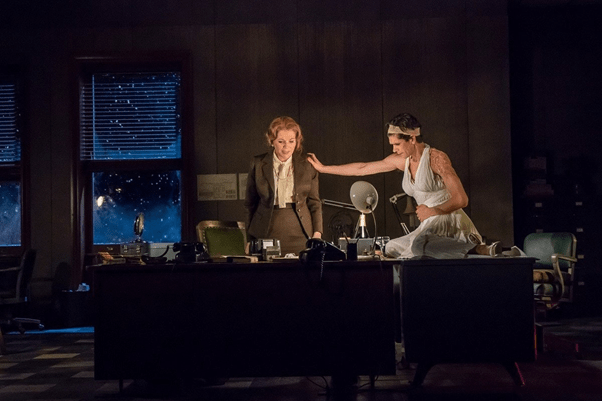

“Says he can’t believe how much I look like her.” (εϊδωλον “image, likeness, simulacrum, replica, proxy, idol”): Reflecting on Anne Carson’s (2019) Norma Jeane Baker of Troy London, Oberon Books.

A very waspish review of this play by Maya Phillips in The New York Times says that:

… while Carson’s writing feels innovative and thematically relevant—her study of femininity and female agency, sexuality and ownership, mythology and celebrity, and duplicity and illusion—…, it still feels lesser than the language.

Phillips, M. (2019) ‘Review: Norma Jeane Baker of Troy at The Shed’ in Exeunt NYC (online). Available at: http://exeuntnyc.com/reviews/review-norma-jeane-baker-troy-shed/

But to separate the themes mentioned in the play from the functions of its language is itself a problem, precisely since it is in and through the production of context through someone else’s scripted language that themes are made potent. Euripides’ play, Helen, is about the use of artifice in the prosecution of the Trojan war and particularly in the re-imagining of the trope of female beauty and the danger to men of that attraction which Helen represents. In a 2019 interview with Sarah Moore, Carson highlighted that her interest in Euripides’ treatment lies in what he does to changing the way Helen as an iconic character interprets womanhood (her ‘moral and emotional quotient’):

the sheer boldness of his reimagining … which was not just a reimagining of the structure of Helen’s fate but of Helen as a moral and emotional quotient. Her passions are here directed not at men or sex but at her daughter. Euripides takes the flat cartoon of the mythic Helen and makes it into a completely different kind of credible human complexity. He widens her heart. How did he do that? Small, amazing changes are what make theatre work.

Moore, S. (2019) ‘Anne Carson on Helen of Troy and Marilyn Monroe: an interview’ in The Literary Hub (online). Available at: https://lithub.com/anne-carson-on-marilyn-monroe-and-helen-of-troy/

We might not notice that Carson discusses Helen merely as a trope, an artefact of written language, if we concentrate, as Phillips does in the review quoted above, on her only as a means of studying ‘femininity and female agency, sexuality and ownership, mythology and celebrity, and duplicity and illusion’. It is as simple a point as saying that such themes are essentially about language and the way language pre-structures our access to notions of femininity and sexuality. And it does so precisely as a prescription of a performance, a prescription open to change -in-performance. Phillips’ review ends I feel rather by suggesting that the plays lack the ability of suggesting any essence of character drama (with a concomitant of ‘depth’ of character implicitly demanded therein) in its actors, so burdened is it by a glittering surface of poetry.

But if that were the case, surely poetry would have failed in its function of offering itself up to be performed, with all the ‘amazing changes’ that performance adds to written script, especially script in highly self-conscious language. It is in this arena that the play is and must be about the other theme mentioned by Phillips – ‘duplicity and illusion’.

A central scene taking up that theme is a prose-poem monologue by Norma Jeane about half-way through the play. Here Norma attributes learning how ‘to fake it, with men’ to her psychoanalytic sessions with ‘Dr Cheeseman’, a clear fictionalisation of the ‘real psychoanalysts’ who worked with the ‘real Norma Jeane’. Yet there is no clarity in all of this discussion either about whether what she learns has anything really to do with ‘faking it’.

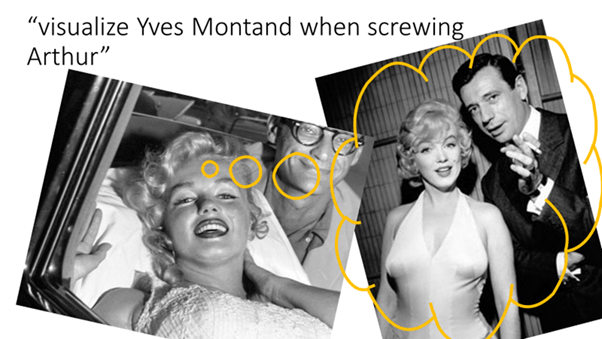

… – one day we were talking about Arthur’s dimpled white buttocks and how I felt no sexual attraction for them or for him, … – and Dr. Cheeseman went into his Lacanian riff, about how “desire full stop is always desire of the Other capital O”, which I took to mean “visualize Yves Montand when screwing Arthur” but that didn’t work for me and what did work for me, oddly enough, was when I found myself one day describing Arthur to Dr. Cheeseman as an Asian boy – Asian boys being Dr. Cheeseman’s own little problem – and so discovering Arthur to be desirable by seeing him shine back at me from Dr. Cheeseman. Is this too weird? I don’t think it’s uncommon. Psychoanalysts call it triangular desire. [1]

Jonathan Mandell, reviewing the play, uses this passage and the scenes which teach ‘The History of War’ in the genre of ‘mock-lesson-plans’ to characterise the writing in a way that is implied by Maya Phillips above. He says: “While there are some clever, enlightening and even entertaining passages, the text can feel like something one would be assigned in school to study”.[2]

Yet the assumption that the play is, or ‘feels’, since both critics use this term, over-academic or overly like a writerly monologue in its concern with language lies more in the critic’s core beliefs about what constitutes the everyday, the ordinary and the normal than in any attempt to read the passage they use to evidence this. And I’d say that is true of whoever performs the text, even Anne Carson herself.

It is possible that the scene we are currently dealing with has a consistent thesis lying behind it from Lacanian discourse theory (even down to a characterisation of the l’objet petit a as the ‘unattainable object of desire’). In such a scholarly reading, the phrase, ‘Desire is about vanishing’ would seem to a reader aware of Lacan, as particularly fitting. But to seek such readings isn’t what I believe the scene does. Instead it dramatizes the effect of a person subjected to Lacanian discourse attempting to make sense of it, lifting significance where they can. This is most clear when Norma Jeane interprets ‘Cheeseman’ as saying to her that she ‘visualize Yves Montand when screwing Arthur [Miller]’.

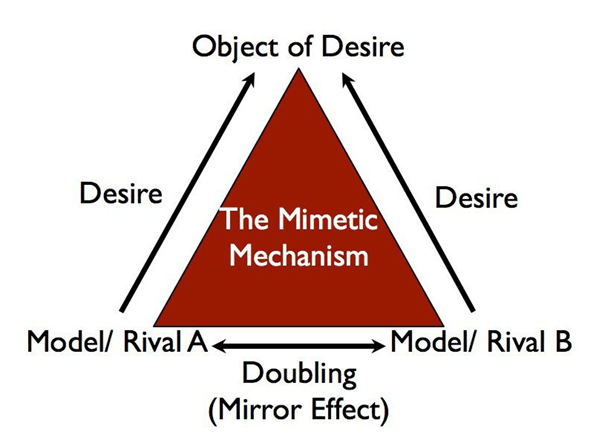

Similarly she adopts psychoanalytic discourse from other sources than Lacan, as reported by the fictional Cheeseman, and blends them with such readings as they seem more or less plausible to her in the narrative of trying to understand herself as ‘faking it’. For instance, as she shows herself learning to see Arthur as an object of desire because Cheeseman desires such ‘objects’ (these ‘objects’ being fictive ‘Asian boys’ at this moment) she weaves into another myth in discourse: “Is this too weird? I don’t think it’s uncommon. Psychoanalysts call it triangular desire”.

The phrase ‘triangular desire’ derives from post-Lacanian literary theory. René Gerard used it to characterise moments when the object of desire is transferred and counter-transferred in a triangle of displacements from one rival angle of a triangle to another – the desired object being the third angle. He also called this the mimetic mechanism since it is how free-floating learns to represent itself inadequately in the everyday world. Thus, If I propose Arthur looks or feels like (represents) an ‘Asian boy’, I awake Cheeseman’s desire for ‘Asian boys’ that is transferred to Arthur and then counter-transferred by representing that ‘Asian boy’ as ‘Arthur’ to me.

Yet the heard text does not demand the schoolboy scholarship I’m demonstrating here. The psychoanalytic borrowings are all about representing the impossible in desire, the thing we can’t grasp but which keeps on wounding us when we become its prey and are captured and possessed by it momentarily. No doubt a comprehensible form of this theory would explicate Norma Jeane Baker’s life as Marilyn Monroe or the one of the two Helen’s in Euripides’ play who becomes a ‘cloud’ to cause rivalry between men who have nowhere to put their desire but in rivalry.

Having said all this, Norma Jeane decides thar ‘most people’ think of ‘faking it’ as just ‘acting’. But she goes on:

Well, in the first place, acting is not fake. And number two, acting has nothing to do with desire. Desire is about vanishing. … Most men like what slips away. A bit of strange. But I digress.[4]

Now by this point Mandell, in his review, finds himself lost. But I don’t think, had he not been thinking at the moment of what he could say in tomorrow’s review piece, he should be. For the play is at that moment at its most self-referential. It is talking about itself as enacted words. It points us to what we see we is the body of the actor acting and that includes, but not only, the mouthing of words and songs. Ben Wishaw reflected on this in an interview with Phillipa Snow. Snow describes the interview thus, starting by citing the French feminist artist, Delphine Seyrig:

“The common denominator that I share with all women is that I’m an actress,” … In Norma Jeane Baker of Troy, …, the role of “all women” is filled by an amalgam of Helen of Troy and the ur-actress, ur-femme Marilyn Monroe: two fatal beauties with a knack for splitting into two distinct real and unreal selves. More literally, onstage, the role of “all women” will be filled by Ben Whishaw, the mercurial and fine-boned English actor who has worked with Carson twice now, and for whom the piece was written. “Which is,” … “a somewhat peculiar thing.”

Snow, P. (2019) ‘Ben Whishaw Is Man Enough to Play Both Helen of Troy and Marilyn Monroe’ in Garage Magazine (16) [online] Available at: https://garage.vice.com/en_us/article/a3bj7b/ben-whishaw-is-ready-to-play-helen-of-troy-and-marilyn-monroe

And therein lies the crux of this paradox of ‘acting’. When one performs a role, we have no reason to see ourselves as ‘fake’. Of a role there is only the possibility of performance, of being acted or not by someone. The choice not to act that role is not always there. Most certainly for Wishaw who sometimes plays under the texts instruction ‘Norma Jeane’, ‘Norma Jeane as Norma Jeane’ and ‘Truman Capote as Norma Jeane’. Under this, Wishaw and his director also invented another character – a man who dictates a story he is writing to be typed by a stenographer, who, in the form of Renée Fleming, also acts as a chorus and/or additional operatic-actor when that is required. Even down to the fact that Capote’s name ‘Truman’ is as indicative of the theme of gender as performance as any other sign in this play, we cannot escape the fact that Carson allows queer theory to play over her feminism.

and that was true.

I can still hear his funny little girl voice – Truman

had a voice like a negligee, always

slipping off one bare shoulder,

just a bit.[5]

We will need to return to the theme covered in the play by discourse on the word ‘ἁρπάζειν “ to take” which shows language at the heart of gender oppression, even to investigate themes like ‘rape’, which unites ‘all-girls-and-women’ of the play. At this point however, I want to stay with the idea of ‘faking it’ as a central theme of both Carson’s play and that of Euripides to which it refers. Helen is known primarily as the casus belli, the ‘cause of war’ in the Homeric (re)invention of the Trojan war. When Carson uses that term in the poem it is to indicate that it is the casus belli which is the true fate of both her and Euripides’ work and that it is solely under control, should they have exerted any control, of a man: “Main point being: he got his war prize, the whole reason he went, his casus belli”.

The ‘taking’ of Queen Helen from her husband King Menelaus by Paris – is described as: ‘‘… all a hoax. / A bluff, a dodge, a swindle, a gimmick, a gem of a stratagem’, in Carson’s words. Yet perhaps all violent and non-violent masculine rivalry about anything is a matter truly of male desire seeking a mere image of his role in the sexualised (because phallic) symbolic order as a warrior. I think this is indeed the reason that Lesson 1 of ‘History of War’ is woven around the word, “εϊδωλον “image, likeness, simulacrum, replica, proxy, idol”.[6] Arthur ‘Miller’ / Menelaus is in love with such an image of sexualised order that goes to war only ‘to get a cloud’.

Arthur is a man who believes in war.

Men standing shoulder to shoulder,

tempered in the fire of battle.

Himself

in a crested helmet,

his army rippling around him

like bees, smelling honey.

Norma Jeane sets this war within a sexual context by forcing out the reference to Matthew Arnold’s Dover Beach, that is already quoted in the Fritz Lang film in which she starred, Clash By Night:

Speaking of ignorant armies though

that cloud scam fooled everyone.[7]

It would seem that the object of desire fools us all and that ultimately the object of male desire for female beauty is as easily described as a blurred vision of a repressed desire in males for other males to compete with, and to ‘ripple’ around them. Indeed the issue is that men become men precisely by taking the ‘Other’ and subjugating it. Carson derives this in word-images, that through Greek and Latin:

gives us English rapture and rape – words stained with the very early blood of girls, with the very late blood of cities, with the hysteria at the end of the world. Sometimes I think language should cover its eyes when it speaks. [author’s italics][8]

That language, in the form of the verb ‘to take’ for example, hides the fact that the shame of violent rape is at the centre of the plays various interspersed ‘lectures on war’. This is true despite their apparent focus on words derived from the Greek. The verb ἁπάτη is then glossed “deception illusion trickery duplicity doubleness fraud bluff beguilement hanky-panky dodge hoodwink artifice chicanery subterfuge ruse hoax shift stratagem swindle guile wile wiles The Wiles of Woman”. In each case ‘the blood of girls’ is made to run because of male desire from Paris to Jack the Ripper.[9]

Rape unites ‘all-women’ in this play – its exemplars being Helen, Persephone, and Norma Jeane/Marilyn. That this behaviour has become specifically gendered has much to do with distributions of cultural and social power in a community but Carson has never believed that it derives basically from biological sex. Her first great critical book Eros the Bittersweet says that violent chase and reluctant acceptance of the fact of being taken ‘is a social expression of the division within a lover’s heart’.[10] Her examples insist that such codes though based on rape actually are demonstrated in marriage ritual but also, and here we see the qenderqueer asserted in the Ancient Cretan right ‘ritual homosexual rape’, wherein younger men are taken by older men. She cites a 4th century historian Ephoros: “If the man is equal to or superior to the boy, people follow and resist the rape only enough to satisfy the law but are really glad …”.[11]

The secret of rape then is social power. That this is most commonly used against girls has a lot to do with how social power is symbolically distributed. Even the common Greek sailor met by Helen in Euripides on an Egyptian beach and re-experienced by Norma Jeane lives his power in sexualised symbols of violence, where emission of spit equates to emission of semen to punish women for male desire.

Says he can’t believe how much I look like her.

Thought he’d never see a pair of tits like those again.

Like these. again.

Goes into a rant about Norma Jeane Baker the harlot of Troy –

that WMD in the forked form of woman! he curses her! he spits on her!

He calls the gods to spit on her.

And so forth.

I let him unload it all.[12]

And beyond all this we have to remember that the woman speaking these words is a man: he is Ben Wishaw, for whom the play was written. The complexities of the analysis of sexual power and the psychology of ‘taking’ lie herein, without ever denying that ‘rape’ remains usually, but not inevitably, the fate of women rather than men because they are marginalised from power in essential ways.

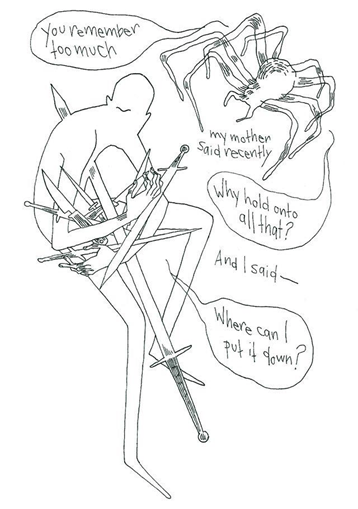

The most troublesome of the lectures on war is on the word trauma, from the Greek for ‘wound’:

τραῦμα “wound” / CHANGING ATTITUDES: …….. Lasting psychological damage, however keen a concern of modern research, does not seem to have interested the ancient poet. / …. / DISCUSSION TOPICS: Compare and contrast catching a spear in the spleen with utter mental darkness. …..[13]

Earlier I took issue with Mandell’s view that ‘the text can feel like something one would be assigned in school to study’. Anyone who has read my blog may feel I have demonstrated exactly why he was right and I was wrong. But that is perhaps because it is so difficult not read the text analytically even though you are insisting that this isn’t how it ‘feels’ to an audience or reader who has not got the text before them. However, there is no doubt that one could invoke notions of the wound from various traditions in psychodynamic theory and practice, from the relatively simple-minded to the complexities by which Lacan and his interpreters talk about the alienated ‘subject’ in language. They are all there but I would insist that they do not demand that you apprehend them cognitively. Indeed if you do, you get lost in trying to make sense of what operates as associations of emotion, of affect.

One care-experienced person’s view of ‘the wound’. There are many such on the web.

And that may be true of life too. The link between self-cutting (important for Marilyn and thousands of other survivors of someone else’s idea of what constitutes mental health), pain and desire (or of being the object of desire) can obviously be explicated through the wound. It is an example of the inseparability of ‘catching a spear in the spleen with utter mental darkness’, the exterior and interior wound, the symbol worn on the skin, sometimes as decoration (in some body art), sometimes as hidden pain. When Phillips saw the play she remembered this line, which she says was repeated, as its moment of extreme self-destructiveness: “Once the cutting starts, a wound shines by its own light”. Such a line unites reaction to psychic pain in a physical symbol of a performed ‘operation’ upon the self. It is felt because it embodies affect in our response to hearing of pain and tells a story about some of the meaning in self-harm.

However, on reading the play, I did not find this piece of language but something even more complex, where even the wound is displaced by an early metaphor from the play, not of pain, but of desire. Thinking of how the Gods see human events, Norma Jeane addresses herself to Helen’s daughter, Hermione, thus:

Does it all make sense to them – war? Clouds?

Fakery? People in flames?

Do they like a good war show? Cover their eyes

at the bloody parts?

Poor gods!

…

We don’t cover our eyes any more, do we – we mortals, we creatures of a day?

We’re more or less blind –

shooting day for night.

And anyway, a heart surgeon told me once,

no need to worry: once the cutting starts,

a cherries

shines by its own light.[14]

It may be that in the production ‘a cherries’ was substituted for by ‘a wound’, which is what Phillips heard. It might have been done precisely to meet the kind of objections to the obscurity of the psychology in the verse. We understand ‘a wound’ anyway because of the surgical context. But ‘cherries’ takes us back to the metaphor it was in the preceding scene, where it also stands for the vagina – the ‘cherry’ that a man gets and takes. In that scene Norma Jeane says, in explaining why she did not dye her pubic hair blonde, : ‘the thing is – talk about a bowl of cherries – most men like it dark’.[15]

Hence we feel in the line ‘a cherries’ the force of how the object of male desire becomes a wound in its own experience. A highly academic response might read the number error in the use of the definite article as a reference to Lacan’s objet petit a, as already mentioned above. But such cognitive contortions are not required in the ‘bittersweet’ feelings of the verse here. Woman has become the wound men seek but then project on the Other in our deepest of emotional responses.

If I had to justify that I would say that the dramatic poem is what it is to “someone, anyone, a person, a certain person, who?” of indefinite gender and that is why the poem’s last lecture is to that ‘indefinite’ and its barely distinguished interrogative pronoun in Greek: τις, τίς. No doubt this may still make the poem a choice of Marmite. But something in me, says it ought not to be so.

Steve

[1] Carson (2019: 22f.)

[2] Mandell, J. (2019) ‘Norma Jeane Baker of Troy Review: Ben Whishaw as Marilyn Monroe! Renee Fleming! Euripides! But…’ in New York Theater (online) Available at: https://newyorktheater.me/2019/04/09/norma-jeane-baker-of-troy-review-ben-whishaw-as-marilyn-monroe-renee-fleming-euripides-but/

[3] MISSING! (SB)

[4] Carson (op.cit.: 22f.)

[5] ibid: 10

[6] ibid: 5

[7] ibid: 2. The last lines of Dover Beach referenced here are: “And we are here as on a darkling plain / Swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight, / Where ignorant armies clash by night.”

[8] ibid: 13

[9] ibid: 31

[10] Carson, A. (1986: 24) Eros the Bittersweet: An Essay New Jersey, Princeton University Press.

[11] ibid.

[12] Carson (2019 op.cit.: 6)

[13] ibid: 9

[14] ibid: 26f.

[15] ibid: 23

3 thoughts on ““Says he can’t believe how much I look like her.” (εϊδωλον): Reflecting on Anne Carson’s (2019) ‘Norma Jeane Baker of Troy’ London, Oberon Books.”