‘[D]etails, chopped up finely, reduced to the state of impalpable dust and arranged … as to multiply their effect many times over and together form an impression of a landscape’.[1] Visualising space in reading and recreating Guiseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa’s The Leopard.

This blog is not what I intended, although it does try to look at the use of ideal space and time in Lampedusa. It is as far though as I can go at the moment. If anyone reads it and find clues to take it further in any direction I’d love you to share them. But if not, never mind …. It’s all about growth for me.

Lampedusa’s great novel came into my orbit in the sixth form in the late 1960s (the first edition of the English translation by Archibald Colquhoun appeared in 1960) and I was introduced to it as a political novel of great interest to the Left by a particularly beloved History teacher. It’s a view I introjected and lived happily with, through all my readings at university. I was bolstered by its role in European political debate initiated by some but not all European democratic Communists from Louis Aragon and, best of all, Palmiro Togliatti, the Father of Euro-Communism.[2] Now re-reading it once again, I’m less convinced that the heart of the book does not lie in its politics, which are profoundly contradictory, but in impressions and images of spaces (spaces in time and place) whose historical meaning is blurred and unclear

I felt that particularly when re-watching (last week) the 1963 Visconti film. For me, the film is still dominated by the image of the bleeding flood of Garibaldi’s Redshirts (the historical shirts were designed for slaughterhouse workers) in early scenes which create an image of popular revolution carrying the flag of Italy into Palermo. It isn’t an image that I find in the novel at all. And in the film, it serves only to enforce later betrayal of the Redshirt cause.

But I still think it significant that image of those, in every sense ‘moving’, redshirts and the lower classes who mainly wore them, together with the cause of profound change of which they are a clear symbol is absent from the novel. Indeed I’d now argue that, in this novel, there is no place for a consistent vision, understood as other as an obscurely defined space, whether it represent something seen in the future, present or past. No spatial image is clear and open.

I think all images and impressions are perceived cognitively, and felt emotionally, to be enclosed or obscured by barriers or some deficiency in the quality and quantity of light, whether it be too much or not enough of it. This I have found too in visual artists, other than in Visconti, who have tried to grasp the novel in graphic, or other visual form. In 2004, twenty artists, including a musician, were invited by the Francis Kyle Gallery in London to visit Sicily at their expense in order to produce works containing still impressionistic images, writing and music that each represented the end of a ‘search of Lampedusa’s Sicily’.[3]

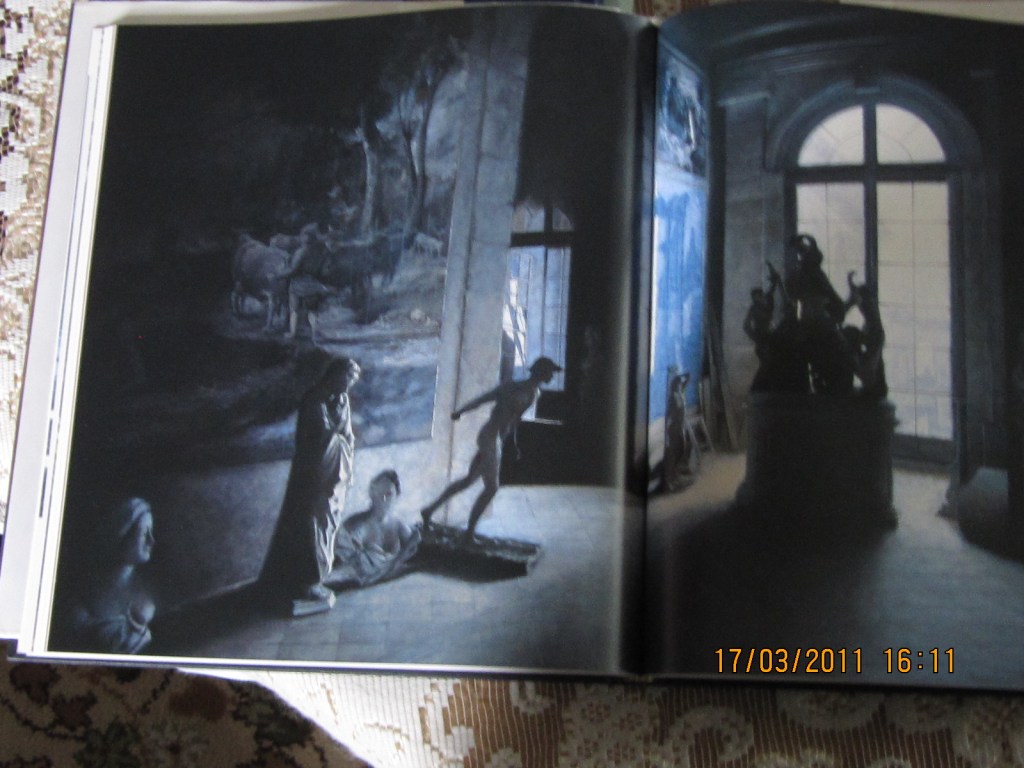

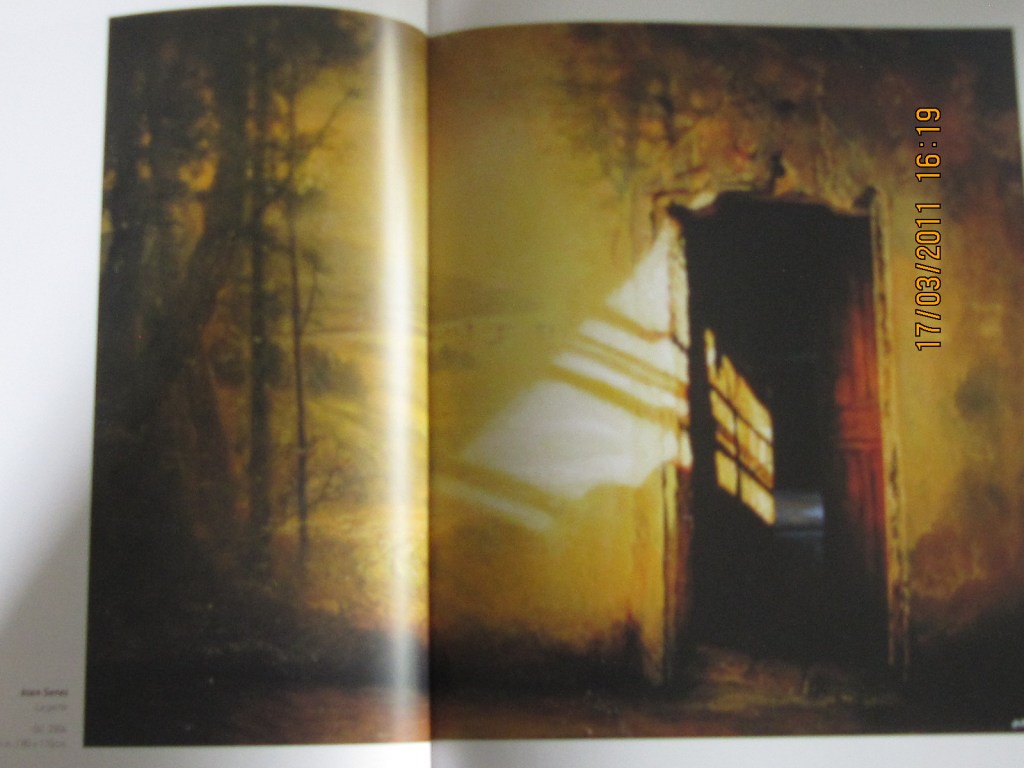

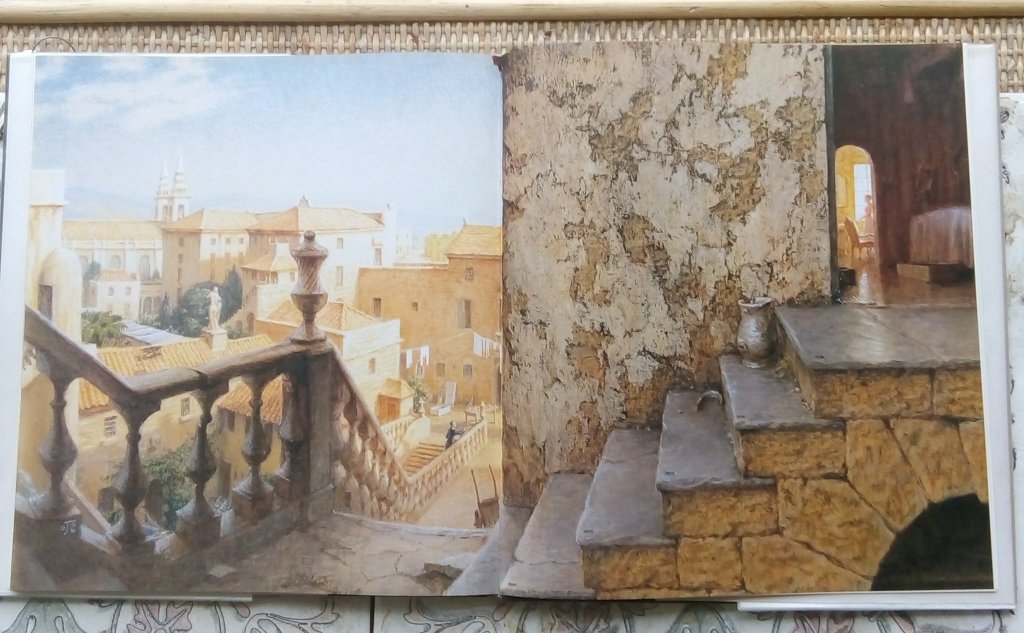

Their response to the Leopard, in particularly those that struck me most, rang bells with how I now read the novel, as these examples show play with space and time. Here, however, I choose only images that obviously express themselves in obscure forms in one way or another.

In each case here the artist employs a complex multi-perspective approach that draws out the strangeness of things, whether it be the spaces or the objects and their shadows in that space. We will return to look at some in more detail, after considering the novel, especially Julian Bell’s fantasy recreation of the palace at Donnafugata with its close reference to both the narrative and moods of the novel. All the artists concern themselves with frames within that of the picture itself, such as margins, doors, windows or drawn lines around patches of colour. In every example there is much reflexive play with the realities that might be presumed to be conveyed as if they were more easily approached through an external shaping of form rather than an internal essence. I think that this reflects my current reading of the novel. I’d now say that it only fails to capture the historical and geographical reality of Sicily because history and geography is not the space it seeks to fill.

The Leopard’s perspective on time and space is perhaps influenced by its piecemeal writing and posthumous editing and publication. Whole chapters were inserted after seeking initial publication. The Donnafugata scenes were, for instance, increased in volume from one to three chapters. One chapter on Father Pirrone’s holiday was added after the second rejection by a publisher.[4] The fragmentation shows in the overall feel of the novel, whilst it insists on itself being seen as preserving a sense of ideal continuity, in relation to which the power of individuals, groups and classes and places is somehow diminished. Thus the Prince ‘notices’ that he is dying with ‘instants of time escaping from his mind and leaving him forever’, yet without discomfort or sense of overwhelming loss.

On the contrary this imperceptible loss of vitality was itself the proof, the condition so to say, of a sense of living; and for him, accustomed to scrutinising limitless outer spaces and to probing vast inner abysses, … this continuous whittling away of his personality seemed linked to a vague presage of the rebuilding elsewhere of a personality … less conscious and yet broader. … some more lasting pile … great clouds, light and free. [5]

This passage strains to escape the constraint of determined limits of space and time in human geographical and historical identity to something larger and freer but that is not easily ‘described’. In fact its indescribability seems another function of its freedom from constraint, as if capturing a thing in language and grasping it cognitively were only a way of literally imprisoning what is strained for. Language here aims for a ‘vague presage’, that is not in consciousness: not bounded or bonded to anything and essentially impersonal and without any other such limit. A similar quality is attributed to the Siren, Lyghea, who says of herself:

“I am everything because I am simply the current of life, with its detail eliminated; I am immortal because in me every death meets, …, and conjoined in me they turn again into a life that is no longer individual and determined but Pan’s and so free.”[6]

The mystical Pantheism herein is probably indebted to Lampedusa’s favourite work by Freud, ‘Beyond the Pleasure Principle’. Impersonal life shares somewhat of the boundless feeling of the Es (id) and much of the Todestrieb[e] or death-drive(s). The yearning for freedom in both passages is escape from the determinism implied by personal definition in the biological, psychological, and social domains and an insistence that nothing in anything changes until everything in it accepts its essential mortality as the condition of ongoing life. Within this idea lie a very certain politics that renounces any continuity based on concepts like the individual body, the person and the class or group. That is, I think, why it is so essential that Fabrizio sees himself as the ‘last’ of the Sicilian aristocracy, as something not transmissible by family or elective choice to the future, not therefore represented in Tancredi.

In The Leopard, Fabrizio is an astronomer and it is this practice that accustoms him in part to metaphysical time-spaces outside of sublunary ones. For this reason, I felt I could only grow my view of this novel by exploring how it dealt with time and space as something that is more than history and geography but impressionistic images of thoughts and feelings like the graphic art I’ve already exampled.

Lampedusa’s long reflective thoughts on reading international literature very often focuses on ‘landscape’. This landscape is not really conveyed by the idea of a representation of an external vista or scene, especially not one seen from only one perspective point as in the history of, say, English landscape painting, but of spaces that contain multiple features that may include interiors, and which engender an image of a whole world traversed by the writer:

… possessing the ability to live independently of its creator, illumined by its own particular light and enriched by its own special landscape.[7]

Tolstoy, Lampedusa thought, was like Shakespeare in that they both used:

… details, chopped up finely, reduced to the state of impalpable dust and arranged with such mastery regarding characters and events as to multiply their effect many times over and together form an impression of landscape.[8]

One could see this as a reflexive comment by a writer on his own practice. An example of such working might, for instance, be in Fabrizio’s and Don Ciccio’s hunting expedition and the evocation of the detail Fabrizio expected to, and presumably did, see in the ‘immemorial silence of pastoral Sicily.’

soon they would meet the first flocks moving towards them torridly as tides, guided by stones thrown by leather-breeched shepherds; the wool looked soft and rosy in the early sun: then there would be obscure quarrels of precedence to be settled between sheep dogs and punctilious pointers, … [9]

These details, such as the leather breeches, describe a distinct enough space but only by also evoking that they are not ‘details’ limited to one specific sighting in time. Instead they derive from time that is continuously repeated from the past (and hence ‘immemorial’) and expected to repeat onwards through future time. This effect is conveyed interactive play of tense and mood of the verbs in the sentence and summarised in the paradox of an immediate change of felt space and time that nevertheless feels to be a perpetually enduring increased distance from the small town of Donnafugata and its ‘new rich’: ‘All at once they were far from everything in space and still more in time’.[10]

This passage is quite unlike the thinly spread and barely noticeable details of either evoked landscape or the passage of felt time Lampedusa finds in Stendhal’s Le Rouge et Le Noir.[11] David Gilmour points out that Lampedusa call his writing magri, or ‘lean’, and spoke of it as of the finest novelistic art whilst writing himself in its opposite mode, of the grassi or ‘plump’, as he describes Proust and Shakespeare.[12] It is highly conscious writing which continually reframes itself between metaphors that are reflexively conscious of their sources in literary conventions and that yet can also convey moments of social and natural realism; somewhat like baroque art and architecture.

It is as if the boundaries between the everyday and the highly worked and artificial in art were continually showing off this paradox by trompe l’oeil effects that characterise the baroque and rococo he knew so well in Sicily. Thence ideas of everyday physical times and spaces overlap disturbingly and pleasingly with ideal external and internal space and time: ‘limitless outer spaces and to probing vast inner abysses’. Flocks can recall tides in the sea but are also brought back to the earth they tread by the meticulously noticed detail of the stones thrown to guide them by shepherds. Country and hunting dogs have as many ‘obscure quarrels of precedence’ as the ‘new rich’ in Donnafugata.

This ambivalent prose is an example of an effect I’ve found throughout my reading of the book on this ‘pass’. Undoubtedly influenced by art images in The Lair of the Leopard it nevertheless made me pause in ascribing easy labels to the politics, history, and geography of this great novel, even though it does still contain such insights amongst its fragments. Now it seems to me about the claims of art to make us see time and place differently. I’m going to tackle this by looking at how two artists visual images have helped me to revision the prose art.

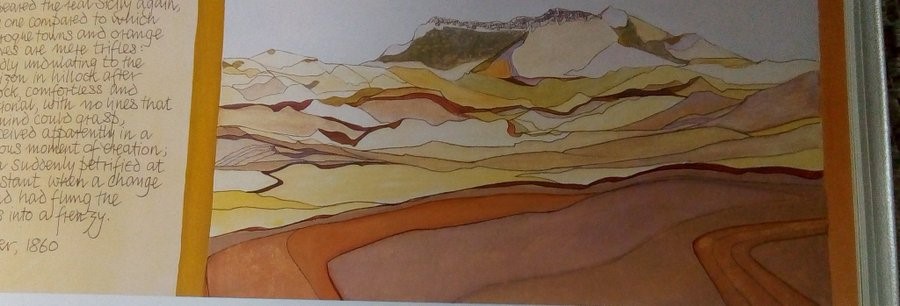

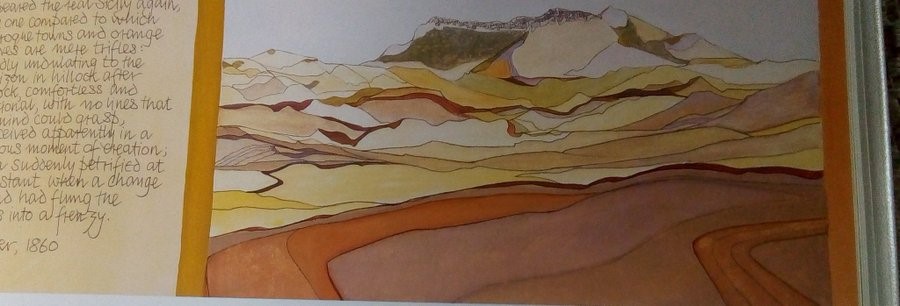

The photograph here inadequately represents Hughes. The sky takes up at least a third of the vertical frame rather than as cropped here and hence the composition of the whole work is not fairly represented. However, what I wanted to ask about it, since the calligraphic setting of the passage to the left of the work as seen here isn’t legible, was in what sense the visual and the narrative prose talk to each other. So let’s see the passage again:

…, there among the tamarisks and scattered cork-trees appeared the real Sicily again, the one compared to which baroque towns and orange groves are mere trifles: aridly undulating to the horizon in hillock after hillock, comfortless and irrational, with no lines the mind could grasp, conceived apparently in a delirious moment of creation; a sea suddenly petrified at the instant when a change of wind had flung the waves into a frenzy. Donnafugata lay huddled and hidden in an anonymous fold of the ground, and not a living soul was to be seen; …

Here I have given a partial sentence at the end not included in the monogram of Hughes’ work. I do so because it illustrates in small the effects of the passage, in its stress on the absence of life-figures and anonymity, a radical depersonalisation in what is ‘real’ in Sicily is a Sicily stripped of its living surface features. The passage haunts because it sees the ‘real Sicily’ as under a cover of living trees that are in essence stripped from the concept by the syntax of the sentence. Hughes chooses therefore not to represent them since only prose syntax can indicate an absence whilst noticing what is irrelevantly present. The real Sicily is ‘among’ the trees but not comprised of them. Rather it tends to an abstraction of space which can conceivably be seen as both a sea and a set of stone planes and layers stilled (petrified) in the moment of ‘a change of wind’. Hence the passage frames the novel between the list binaries of which it is neither extreme; wet and dry, changeless, and changing, in frenzied motion and still, real and merely apparent, named and anonymous. The invisibility, in this picture of Donnafugata, a place with history and geography, is a means of suppressing the human endeavour other than in terms of a more basic spatial contrast between what is permanently living and in creation and that which is petrified or stone dead.

Hughes shows this by highlighting patterns and layering of colour that are nevertheless incomplete patterns – as in the effects of purple that run laterally across the tempera painting. We strain to see relative depths and heights but the picture remains defiantly flat, all its effects being in the change and frequency of pastel coloured shapes, particularly those clustering to the top of the hill or wave. At points we think we may see a river but there is nothing in the coding to rationalise that perception. The effects here could be of perceptive – but they might also be of more abstract size, form, and colour contrasts. Indeed, this is even more the case in Hughes’ painting The Prince declines Chevalley’s offer (2005) where rational shapes, representing the Ancient Greek temples of Agrigento contrast with abstract shapes caught between rise and fall, motion, and stillness.[13]

In Lampedusa’s literary commentaries landscapes may be townscapes as well as tradition landscapes, but they also may be interiors as well as exteriors as well as a mix of the two. Many artists in Kyle’s The Lair of the Leopard respond to such opportunities as indeed does Visconti in his use of vistas of baroque door within a linear perspective guiding us through rooms with many sources of light and causes of shade. The use of door and window frames to create multiple perspectives, with their own vanishing points is a common device. It tells us a lot about the novel’s obsession with what visual perspectives can make ‘huddled and hidden’ as in our last passage. Lampedusa even admits that this device is so common in his novel it may be as much a subterfuge as the use of mystery by Sicilian lands people:

…’ in this secret island, where house are barred and peasants refuse to admit they know the way to their own village in clear view …, here, in spite of the ostentatious show of mystery, reserve is a myth.[14]

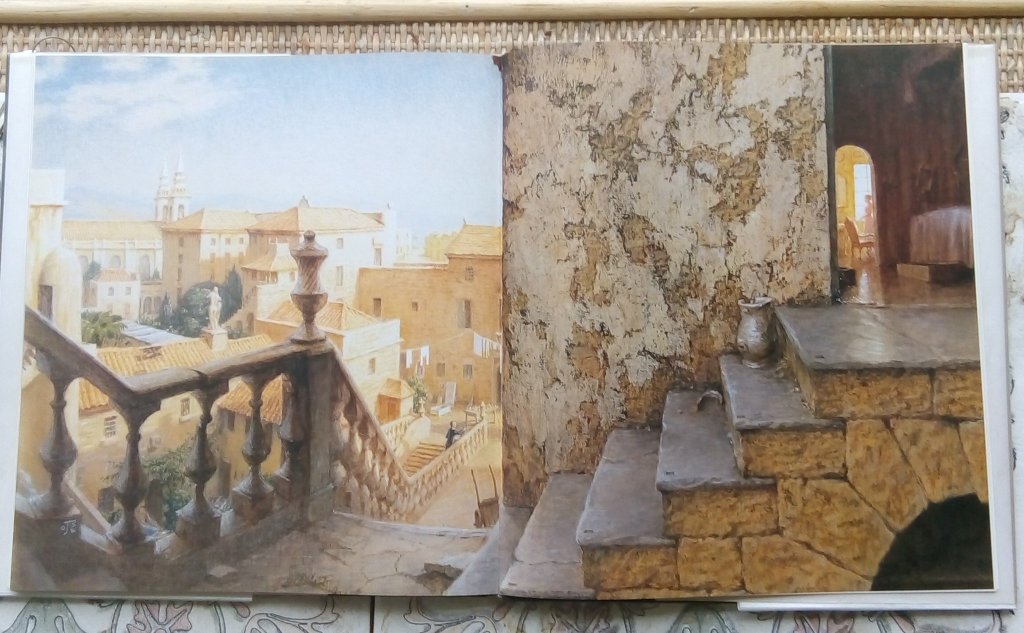

Of course theatrical use of secrets and reserve is a characteristic of Baroque art anyway, especially the Baroque version of the Gothic in Horace Walpole, a writer Lampedusa knew if not one he claimed to value. Interiors can have secret or hidden access to exteriors or other, sometimes endless other interiors in such structures of architecture, or indeed writing – witness The Castle Of Otranto. Hence confusions of outside and inside characterise the visual art in Kyle’s collection. Above, for instance, see Senez’s La Porte, in which interior walls project half-lit scenes from the external world but in which shadows and unexplained damage dominate and beyond the door is only darkness. Dael’s Comme des Ombres has an obvious play of perspectives, multiple light (and shadow) sources. There are many great examples in the book but I want to end with Julian Bell’s Hide and Seek in Donnafugata, with its obvious nearness to the text and narrative of the novel.

This beautiful painting seems to celebrate the baroque but its narrative and iconic features also play on Gothic secrets and motifs that Lampedusa made central to his picture of sexual foreplay in the lovers’ ‘mysterious and intricate labyrinth of their own’. Freud, whose work Lampedusa knew extremely well, characterises such foreplay as a game of delay fighting against the wish for culmination, of emergence against negation and other repeated patterns. We see such games here in the hide and seek motif where almost everything may be hidden or not.[15] Usually both possibilities play on even in our attempt to understand the action of characters:

Tancredi did not realise, or he realised perfectly well, that he was drawing the girl into the hidden centre of the sensual cyclone; and Angelica at that time wanted whatever Tancredi did. Their wanderings through the seemingly limitless building were interminable; they would set off as if for some unknown land, and unknown it was because in many of those apartments and corners not even Fabrizio had ever set foot – …[16]

The passage plays with the fact that what is ‘hidden’ at the centre is in fact known to both participants – they look for each other, and at the same time a room, in which consummation of their meeting can be again delayed. The pictures of sexual frustration in these and other characters is very much on the surface. Even the elderly retainer Mademoiselle Dombreuil ‘lay down on her lonely bed’, where she ‘would stroke her withered breasts and mutter indiscriminate invocations to Tancredi, to Carlo, to Fabrizio …’.[17]

But what we might note here yet again is that the palace must be experienced as ‘seemingly limitless’ space-time, even in only in a much lighter mode that the continuities offered by death, ‘interminable’. This is mimed in sentences as Baroque-Gothic as the scenes, mounting and falling excitements, open passages, and enclosure by ‘grilles’ which they aim to represent:

… it was not difficult to mislead anyone wanting to follow; this just meant slipping into one of the very long narrow and tortuous passages, with grilled windows which could not be passed without a sense of anguish, turning through a gallery, up some handy stair, and the two people were far away, invisible, …[18]

One or more of those ‘wanting to follow’ but ‘mislead’ is the novel’s reader. Now Bell builds some of these narratives into his painting by employing complex perspectives in which he hides his figure, secreting them so that, as we seek and find them, we experience in our wandering gaze somewhat of the giddiness of circling staircases, open and closed passages through portals and semi-independent lighting sources for each perspective.

Kate Quill describes the 2 figures of Tancredi and Angelica as ‘tiny figures seen at the bottom of a stairway and silhouetted in a faraway window, like memories or ghosts’.[19] On our search for her we pass one of the many beds on which the lovers never reach fulfilment in the novel and beneath the entrance to these room is a dark passage portal. Dominating most of the right of the painting is a decaying facia wall whose patterns reveal some of the muddle and time-bittenness of the structure. This old wall contrasts with the light which obscures the shape of the tall Gothic buildings to the left. If the sun makes vague it also gilds and makes young, as in the nude statue central to the left panel. To get into the shadows and to Angelica we pass unused and broken object, a near upturned cart, a broken mosaic stone at the intermediate landing and a broken jug with its handle separated from it on the bold stairs that crowd into the picture-plane.

But for me the main surprising effect of opening up perspectives are those which contrast effects of looking up to supposedly high structures and down to deep recesses. I’d know this picture a long time before my high was called down to the lowest courtyard we see over the balustrade as seen on this detail.

The effect on the viewer is to make us the feel the fall to which this recessed depth invites us, and perhaps the place where it would culminate. In this detail we see, what it took me a long time to see, almost hidden in plain sight as it is, cracks in the balustrade railing, structure, and ornament, that invite an empathetic vertigo and hard-to-name fear. This is not just play, it is danger. In my view, it shows us the constant changes of tone in the novel itself – from life to death, dark to light, height to depth and play to something uncontrollable about death which we might need capture within the art presented.

Lampedusa and Bell use space here as a kind of means of transference of the anxieties of the characters, sometimes ones unknown to themselves, onto others – and here onto reader and viewer. We know Lampedusa was a reader of Freud. His wife was the Director of the Italian Psycho-Analytic Society and Gilmour tells us that she would read case notes to him from her patients. In the very same ‘hide and seek’ passage I’ve already quoted, Lampedusa says that everyone is drawn into the loving couples’ secretive erotic game, ‘as psychiatrists become infected and succumb to the frenzies of their patients’.[20]

I leave this blog as unsatisfied as no doubt are its readers that I have managed to reach any firm conclusion about the use of ideal space and time in Lampedusa, but I think the pursuit is worth the biscuit. If you find clues I’d love you to share them. But if not, never mind …. It’s all about growth.

[1] Guiseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa ‘Macbeth’ from ‘English Literature’ (1962: 130) in Guiseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa [trans. Colqhoun, A., Gilmour, D. & Waldman, G.] The Siren and Selected Writings London, The Harvill Press..

[2] Gioacchino Lanza Tomasi [trans Gallenzi, A. Nichols, & J.G.] (2013: xiv) Guiseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa: A Biography Through Images Richmond, Surrey, Alma Books Ltd.

[3] Published as Kyle, F. (ed.) (2006) Lair of the Leopard: Twenty artists go in search of Lampedusa’s Sicily London, Third Millennium Publishing

[4] See Gilmour, D. (1988) The Last Leopard: A Life of Guiseppe di Lampedusa London, Quartet Books, pp. 138 – 158.

[5] Guiseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa [trans. Archibald Colqhoun] (1996 op.cit.: 164) .

[6] ‘The Professor and the Siren’ p. 81 in Guiseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa [trans. Colqhoun, A., Gilmour, D. & Waldman, G.] (1962: 119ff) The Siren and Selected Writings London, The Harvill Press.58 – 84.

[7] On ‘Dickens’ from ibid: 151.

[8] On Shakespeare’s Macbeth in ibid: 130.

[9] Guiseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa [trans. Archibald Colqhoun] (1996 op.cit.: 64)

[10] ibid.

[11] Lampedusa (1962: 170f.) op. cit.

[12] Gilmour (1988: 122) op. cit.

[13] Kyle (ed.) (2006: 48f.)

[14] Guiseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa [trans. Archibald Colqhoun] (1996 op.cit.: 25)

[15] Hide-and-Seek is a form of the Fort-Da game in Lampedusa’s favourite Freud book Beyond the Pleasure Principle wherein he traced the beginning of repetition compulsion and death instinct)

[16] ibid: 107

[17] ibid: 106

[18] ibid: 107

[19] Quill, K. (2006: 61) ‘Looking At The Leopard’ in Kyle, op. cit. 58 – 63

[20] Lampedusa (1996: 106)

One thought on “‘[D]etails, chopped up finely, reduced to the state of impalpable dust and arranged … as to multiply their effect many times over and together form an impression of a landscape’. Visualising space in reading and recreating Lampedusa’s ‘The Leopard’.”