Two blogs on the Bensons: No. 1 of 2:

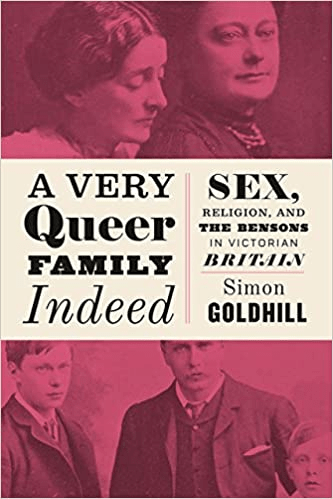

- Writing the complexity of a family: Simon Goldhill (2016) A Very Queer Family Indeed: Sex, Religion and the Bensons in Victorian Britain Chicago & London, The University of Chicago Press

- How then do we read novels queerly, avoiding oversimplifying categories? Reading E. F. Benson (1916) David Blaize London, Hodder & Stoughton. This second blog can be accessed here: https://stevebamlett.home.blog/2020/06/05/how-then-do-we-read-novels-queerly-avoiding-oversimplifying-categories-reading-e-f-benson-1916-david-blaize/

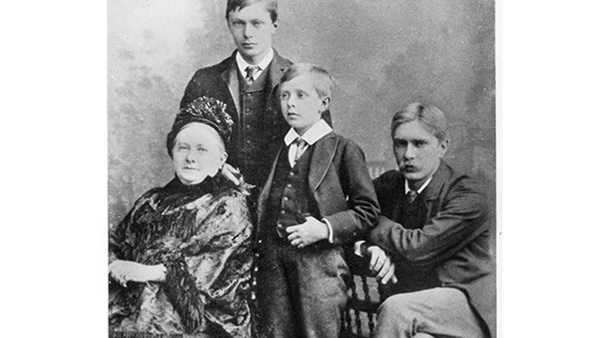

I felt the need to write these blogs after being ‘blown away’, as they say, by Simon Goldhill’s insistence that queer history is not, or not just, the story of LGBTQ+ people from history. Indeed it often is about the complexity with which we ‘name’ emotional and cognitive self-and-other-identifications, even at the level of interpersonal bodily experience, like a kiss. Indeed the book ‘starts with a kiss’ (as the song goes) that the already established adult young man Edward White Benson (who was to become an influential Archbishop of Canterbury) gave his 12-year-old fiancée, Minnie, whilst she was sitting on his knee.

At this august point she, with what informed consent we might guess, took on the role of future wife in the encouraging presence of her mother. It deals with how both Minnie and Edward, and their incredible children, dealt with the love affairs of mother Minnie as an adult with other women whilst maintaining simultaneous devotion to the Archbishop. Influential themselves in ecclesiastical, literary, and political life, the male children continually rewrote the story of those engagements and only semi-secret narratives. Likewise the children, most of whom had exclusive (or non-exclusive like Minnie) same-sex relationships of one kind or another as well as other ones sometimes, went on to write and act transitions in the life of a national class bound culture.

Goldhill shows us that it is to resist complexity to say that we can confidently name these relationships as we describe them in writing by the terms gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transsexual. Ben says his work is ‘a plea for the value of complexity’.[1] In speaking of the difficulties involved in naming the relationships dealt with, by the Bensons as writers of letters or public texts and by himself, Goldhill says:

… each was aware and expressed their awareness strongly of how they were out of place – not usual, normal, typical – …

The Bensons are a very queer family indeed, then, not because they are sexually, intellectually, socially transgressive – though there are many ways in which they are just so, just as there are many ways in which they are as establishment as it is possible to be. … Queerness is what makes naming and the understanding that comes with naming, uncertain. (One should always hear the query in queerness.)[2]

The first blog reviews Goldhill’s brilliant re-reading of what the person in history means and how historical agency is understood. The second awaits me reading David Blaize for the first time. I want to see what the consequences of Goldhill’s achievement intellectually is on my reading of that minor novel, without confining myself entirely to what Goldhill says of it. It was if minor, read by so many young male soldiers on the front line.

_______________________________________________________________________

Writing the complexity of a family: Simon Goldhill (2016) A Very Queer Family Indeed: Sex, Religion and the Bensons in Victorian Britain Chicago & London, The University of Chicago Press.

Goldhill’s book, whilst it is a history of how family and personal lives touched on and were embodied in institutional and political lives, also takes on certain forms of modern history of social identities.

The oddity of the Bensons, the ways in which they do not conform to conventional models of sexuality, provides a refractive historical mirror for our contemporary drive towards labelling the pathologies of desire. True queerness is what is hard to name.[3]

The aim to critique a ‘contemporary drive’ is pointed at books which categorise and label types of desire, fetishizing in the process the names of those types. Whilst showing those ‘modern’ name-labels fail to understand the complexity of a ‘Victorian’ family’s inter-relations within itself and with external society, it also admits that contemporary label may not itself be more than a conveniently oversimplified way of categorised contemporary desire too. I think I hold that truth to be self-evident.

The term ‘Victorian’ too came in use and has somewhat stayed in use as a way of referring to a kind of rigidity and repression of wider sexual nature in Lytton Strachey’s Eminent Victorians. It suited a society claiming a kind of openness about the privilege of difference. However suited to Bloomsbury this idea of the outmoded Victorian was, especially in its emphasis on the privileged classes, it is oversimplified by Strachey. Virginia Woolf, at least in her private correspondence, is used by Goldhill to make his point that wherever we try to name things that are genuinely complex to ease our worry about their destabilising queerness, we lose the essence of what we are trying to describe. She says this is true, in describing love between women, from whatever ‘historical age’ these women derive. That view is sort of axiomatic of Orlando.

…: Where people mistake,” she wrote, “is in perpetually narrowing and naming these immensely composite and far-flung passions – driving stakes through them, herding them between screens.” Naming such queerness is like driving a stake through its heart …. So, she concluded pertinently, “what is the line between friendship and perversion?” …[4]

With this I am content. In our own time the queer revolution is an attempt to free people from labels that restrict complexity in identity. It has spawned social movements like the LGB Alliance to assert that sexual orientations are essences shared by a distinct group, not the potential of a mixed and queer range of desire across persons, and sometimes one person. So too in Gender Critical Feminism, asserting that gender is not merely essential but a pre-determined biological fact. These movements belong to a conservatism that is as rigid as Strachey defined the ‘Victorian’ as being. The notion that histories of identity are separable from intersecting histories of cultures and power feels to me an obvious nonsense. A central historical given of reading this book is that terms describing, say, queer sexuality, but also queer form of religion and fiction, were not fixed and stable during that supposedly stable Victorian era. The language for naming things, especially forms of sexuality and, to some extent, gender were in an enduring age of formation.[5] Arthur is captured as queer because, ‘although he cannot stop talking about it, he never can quite find the words for himself’.[6]

Hence this book ties the queerness in and of the Benson family to topics and domains equally definitive of the family and the range of its responses to the worlds they lived in. At its heart is the experience of ‘conversion’. And in speaking of Hugh Benson, his conversion to Catholicism via the Oxford Movement is clearly shown to intersect with discourses of gender, sexuality, class, and identity. When we name identities, especially those to which we are subject by conversion or change, we don’t expect one aspect of that identity to name nor to reduce the meaning of the others, although that is sometimes the case with revelatory gay biographies of the past. So if, “Hugh’s conversion was the defining point of his life”, it is so only in understanding the process and rational of conversion as complex set of patterns occurring in and between self, culture, and historical dynamics. Conversion is not explained by any one force in history, culture or identity-formation (the subject of the Bildungsroman).[7]

Patterns of conversion are thus integral to this history of change, both as a narrative form and as a mode of knowing. The peculiarity of this family and their personal stories of change are also a history of a culture’s development. But the relation between the story of a culture and the story of a family is fraught and hard to disentangle.[8]

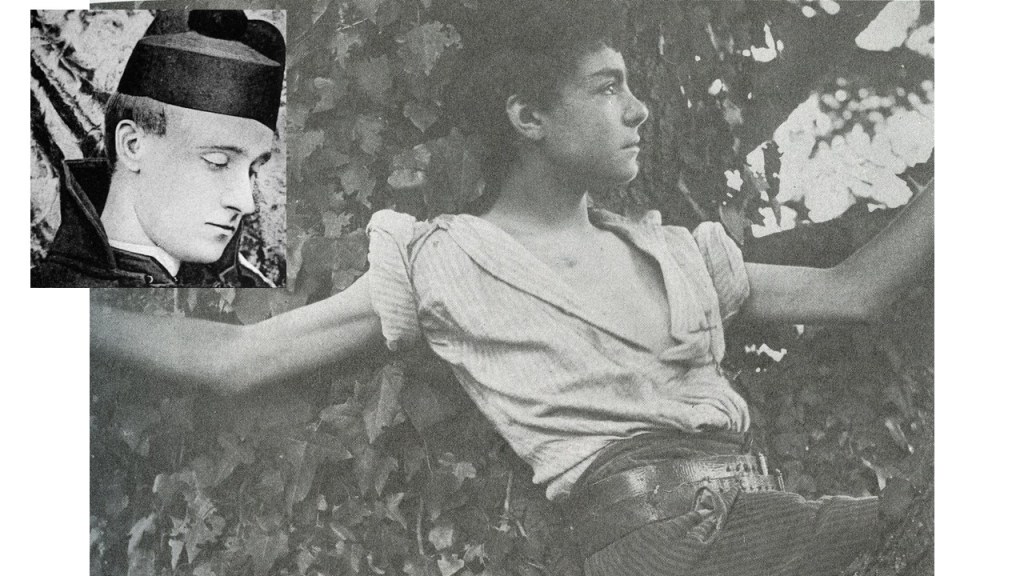

This is so important. Families undergo conversion experience in the meaning of the individual lives as they develop and in the meaning of the individual’s family experience to the person. This relates to their personal, sexual, and career developments and the meaning of their interventions into history. Such meanings can’t be confined to one type of conversion, such as I became a Catholic or a ‘muscular’ Anglican or a writer or bishop or bisexual, gay or heterosexual. These and other ways of knowing what we are becoming or have become are patterned in complex ways, such that for Hugh, conversion via the Oxford Movement, was also a conversion to ways of articulating gendered masculinity, sexuality, and politics as well as religion. And it involved Hugh’s close gay-religio-literary alliance with Frederick Rolfe, aka ‘Baron Corvo’, his Cambridge bathing companion and early gay pioneer in the view of the ‘history of homosexuality’ that Goldhill finds inadequately simple.[9] When that relationship broke down, Rolfe wrote scathingly of Hugh under the name ‘Bobbugo Bonson’. It was a thinly veiled reference to Hugo Benson , whom his family and friends knew under the name ‘Robert’.[10]

Arthur Benson, Goldhill finds never quite swung to any one outcome of conversion – his sexuality, religious nature and writing and reluctance to grow up in some ways being a kind of ‘havering’: ‘tensions of reticence and disdain, critical dismissiveness and social form, recollection of fear and longing for love,…’.[11]

Charles Kingsley, for instance, who was the radical writer of Alton Locke, a novel of conversion and class politics, took on Newman and the Oxford Movement by seeing their interests in conversion to ritual practices in the Church in ways that ‘seemed a sign of “unmanliness”.[12] Such was the case of many practices for Kingsley in degraded effeminate, over-civilized’ races, ‘exhausted by centuries during which no infusion of fresh blood had come to renew the stock’.[13] In this one sentence, from Hypatia[14], Kingsley raises issues of how gender is articulated, the role of sexuality in national cultures and contemporary debates on eugenics. These same issues will be found woven together in the life and fiction of Fred (E.F.) Benson, the life and religio-political mission of Arthur (E.C. Benson) and, as we have seen the life and ecumenical career of Hugh. Sorting out where the gay male element of all this inheres is a complex and perhaps purposeless reduction of the way the issues pattern together.

So this is the contribution of this book. It uses the notion ‘queer’ to get nearer to the ways in which lives were seen by their subjects across a number of domains where norms where in the process of changing and in which they emerged as multiple versions of what they were simultaneously or in correlation. And such emergent types of conversion or change of not only persons through history but also family groups and narratives about both, which the age called forth as its speciality in biographies, autobiographies, and epiphanies. Nothing changes but as within the systemic co-changing networks Freud called ‘family romance’:

… a marriage of conflicting desires, the interaction of widely different ages in erotic bonds, different generations responding to each other.[15]

To read the book fully then is to be aware that its sections may name different foci of interest but that all are bound up in the difficulty of ‘naming’ the things undergoing transformation and/or emergence within the Victorian period. The first section is nominally on the obsession with writing especially about self and the formation of selves generally (bildungsroman). The second about sexuality and wherein queerness comes into its own sphere of sexuality but only to be applied both prospectively and retrospectively. The third about religion and religious change and conversions. All are about change in history as a Benson ‘family romance’, all are suffused with the liminality and queerness change brings about. All bring to bear on questions of ‘form’: in literature (aka the Bensons but also their links to Henry James amongst others for whom ‘form’ in literature was to be both overturned and yet absolute), in sexual and ‘other’ unions, in religion and the liturgy, and various other life-domains: ‘Form meant a great deal to Arthur Benson’.[16]

And yet when talking about what is ‘sexual’ in literature, Arthur is at a loss for forms of suitable expression and categorisation. It is so not homely that it is, in Freud’s term ‘unheimlich’ or uncanny.

There is no place, no sense of fitting in when it comes to sexuality, not just as a subject for literature but as also a way of writing a life. It is not where he is at home.[17]

This is a rich book that no simple summary like mine will get right. It should be read and, despite the dryness of my description is a very lively read. What it inspired in me was a wish to read E. F. Benson’s David Blaize. This is a novel I have put off for a long time but it is a fictional autobiography, deals with sexual transitions and metamorphoses and the historic morphology of religion in education, architecture, and modes of life. As I write this and set up the blog, I have not finished the novel but have grown to enjoy it. Thence when finished I’ll blog on it in the light of Goldhill’s statements on it and my own ‘take’ on the novel itself, as a form of life, sexual and gender excursion and play with changing systems of belief, including the ‘hero-worship’ Thomas Carlyle made so fundamental to religion.

When I have completed this second blog it can be accessed from this link:

Steve

[1] Goldhill (2016: 298)

[2] ibid: 287.

[3] ibid: 216

[4] ibid: 193

[5] ibid: 133. Re; issues of ‘lesbian’ sexuality see ibid: 175, Re sexology see 1788ff.

[6] ibid: 149

[7] ibid: 285f.

[8] ibid: 286

[9] ibid: 247

[10] ibid: 245f.

[11] ibid: 281

[12] ibid: 200

[13] Kingsley Hypatia cited ibid: 201

[15] Freud’s term cited and applied ibid: 215

[16] ibid: 271ff.

[17] ibid: 129

2 thoughts on “Writing the complexity of a family: Simon Goldhill (2016) ‘A Very Queer Family Indeed: Sex, Religion and the Bensons’ (1 of 2 blogs)”