“Possible failure or disaster seemed to lurk round every corner: … Why on earth does one go submitting oneself to such torments?”[1] Creativity and imminent disaster in Stanley Cursiter: reporting on Beasant, P. (2007) Stanley Cursiter: a life of the artist Kirkwall, Orkney Museums and Heritage

I’d like to start with the usual personalised note, explaining why I write at all. Sometimes I get a conviction about something that is so strong it must lie deeper than I know. That has to be written out by looking at the stimuli that provoked the conviction. But I still find the need makes demands on me that I can’t altogether meet, even were I to try much more than I now allow myself to do. Hence writing a blog and not worrying too much about how, or whether, it is received by others is the best bet. That is possible when you are retired from more overt demands on how you self-display, from ‘paid work as an employee’ that is. But I remember that feeling that seemed to motivate work and underlies my endeavours still for better or worse: the fear of failure. Elliot and Thrash in a study trace it to a psycho-affective cognition that is transmitted intergenerationally:

In essence, by transferring fear of failure to their children, parents saddle their children with a dispositional burden that they must carry with them into each new achievement situation and that affects the goals they choose to pursue in these achievement settings.

My italics. Elliott A.J. & Thrash, T.M. (2016: 968) ‘The Intergenerational Transmission of Fear of Failure’ in PERSONALITY AND SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY BULLETIN Vol. 30 No. 8, August 2004 957-971 DOI: 10.1177/0146167203262024 Available at: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.987.7233&rep=rep1&type=pdf (Accessed 27/05/2020)

Now I don’t want in using this study to validate its theoretical and methodological assumptions, but I do think it registers an association between a commonly co-occurring cognition and affect in front of endeavour that I find in self and others, including the time I spent in therapeutic treatment of others with depression and anxiety.

These issues came to a head again in re-examining the work of Stanley Cursiter. The motive for that was when I found myself generalising about Cursiter’s non-Futurist works. I had chosen Rain on Princes Street (1913) as the focus of a brief essay on the crowd meme in Vorticist and allied art around the time of World War I on a course I did. I love the painting and had recommended it to a lover of art interested in Nevinson on Twitter. I found myself saying something like: ‘The rest of Cursiter’s work was all highly conventional landscapes, portraits and interiors’. No doubt I’d read that somewhere but on reviewing what I’d said I became aware of how shallow a judgement that was in my adoption of it. In what follows I’ll introduce how I have been developing my thought about Cursiter following reading this book, before returning to why it relates to the sense of imminent disaster that is ‘fear of failure’.

So to try and go a bit deeper into Cursiter I read the whole of a book I had used in part in the past – no hardship since it’s a beautifully written but brief life with additional essays on the range of genres and ‘styles’ addressed in his career by different experts. In that book we learn something of an only lightly expressed and yet ever-present conflict in the man, that seemed to me as I gazed at the pictures in it and reflected present in the painting too. It might be expressed as a kind of ambition that reached grandiose proportions, at least in intent, squashed by a sense of reality that offered to him less flattering reflections of his capacity. One could, and I’ll try later, relate that to the extraordinary fact of his almost single-minded brief pursuit of a Scottish Futurism but even experts on this brief period show that there were important links between the underlying theories of Futurism in Marinetti and Severini, whose paintings and writings he knew. Thus in this book Jeanette Park shows how theories of sensation, dynamism and ‘simultaneity’ in time-space adopted from Bergson by the Italian futurists are also useful in understanding his seascapes:

Cursiter’s sketch books of 1912/13 reveal an avid fascination for compositional designs of the ‘modernist’ type, especially those that deal with what could loosely be called ‘force lines’ and their impact on perspective. … the sketch book drawings lean mainly towards organic forms, such as the geological forms of cliffs or quarry faces, the structure of the drawings deals with the effect of one solid plane as ai collides with another. Another theme experimented with at this time was the movement of the sea. He deals with the rushing momentum of the tides as they crash into the static solidity of the rock. Although they may not seem very Futuristic, the sensation of motion, sound and force are all being explored.

Park, J. (2007: 131) ‘The Futurist Works’ in Beasant, op.cit. 125 – 136.

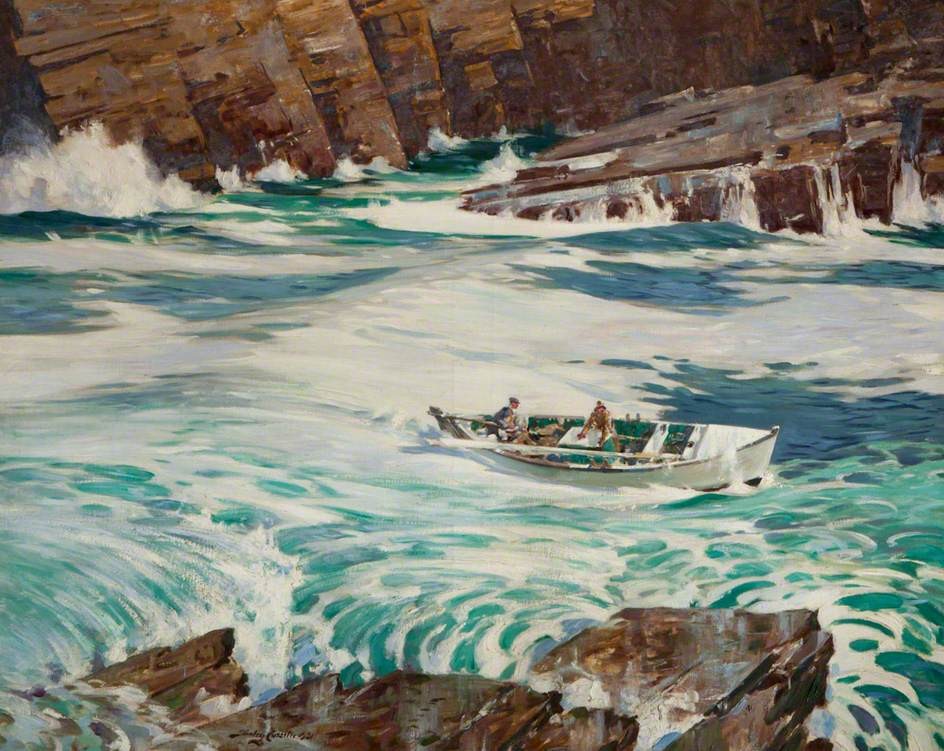

In particular, Park mentions a huge (110.5 x 127 cm.) and momentous painting I’d already become fascinated by: Linklater and Greig (1931).

In the ever-present view, even in his admirers, of Cursiter as a middling painter, and even he is called in by some to show the ‘fact’, Cursiter was not up to such grand statements in a ‘studio’ painting such as this. Neil Firth, in this book, says the painting has ‘impact’ but rather damns it by saying he, and Cursiter too by implication, thinks it’s ‘bravura of ( ) studio statement’ lack the ‘”spontaneity” and “sparkle”’ when contrasted with en plein air ‘smaller oil sketches’ of more sedate Orkney coastal landscapes.[2]

John Morrison’s more admiring view puts the larger Orkney seascape paintings in central position to understanding Cursiter’s achievement. He traces their effects to principles lying deep in the writings of Paul Cézanne. He quotes Cursiter’s lecture on that painter, comparing him to the Impressionists. Cézanne, he writes, felt the Impressionists too concerned ‘with surfaces and appearance’ :

It was his great merit that he as able to convey a complete sense of the weight and shape of the objects he was painting without sacrificing the brilliant light and colour …. His landscapes have an air of permanence about them.

Cursiter in 1935 lecture cited Morison, J. (2007: 123) ‘The Orkney Landscapes’ in Beasant op.cit. 117 – 124.

Now in 1935 any comparison with Cézanne suggests that Cursiter’s artistic ambition was high. Of course the comparison is tacit rather than asserted but Morrison argues that it explains how and why Cursiter uses paint in a way that renders it visible and concrete to our eye rather than to create an appearance of a scene that is being copied. We are meant to see the artist’s brushstrokes and the marks they make on the canvas. It is these that give a sense of ‘permanence’ to painted objects and to the project of being a painter rather than a landscape photographer. This may also suggest why he, like Picasso was known for ‘unfinished’ paintings in which canvas left bare formed part of the painting.

In the 1930s Cursiter was still considering whether taking his daytime job, as the National Gallery Of Scotland’s Director, was too ‘ordinary’ for his powers. An unknown correspondent in 1933 tries to counsel him in relation to his job as ‘being so inadequate an employment’ of his ‘powers’ and the constraints of having to ‘fit into a “normal scheme”’. He is the correspondent says a ‘creator, first, last and all the time (writer’s own emphasis)’.[3]

What I’m struggling to convey here is that Cursiter often looked to achieve ‘permanence’ in his subject matter and in his artistic achievement and reputation. He could look at that desire as exemplified in Cézanne’s career and paintings and as almost superhumanly ‘creative’ in its meaning, but, at the same time he was riddled with doubt about his ability to achieve that status in a way that would endure, at least in the Scottish tradition.

Hence then the fact that Linklater & Greig is a painting about the sensation of achieving something in the teeth of possible disaster. Its figures may themselves be important. A master local mariner, Robert Greig is being steered through a difficult pass in the seas by Eric Linklater – hand firmly on the tiller. The assurance speaks out from the 1933 portrait of Linklater, who loos down benevolently from a large portrait directly at the viewer.

Linklater is better known as a novelist of the time when he was artistically and politically tied to the Scottish Renaissance movement and Scottish nationalism. The painting precedes Linklater’s move to Orkney, which was not his native region, but not the beginnings of his ambitions. In 1950 Cursiter painted Linklater in the foreground of other Scottish Renaissance writers (without significantly the troublesome chief Hugh MacDiarmid): Edwin Muir, James Bridie, and Neil Gunn. But in 1931 Linklater, like Cursiter, has still only just achieved some early fame (from 1929 it is often said). He is still facing the issue of how permanent and forceful his reputation will be.

Linklater & Greig in my eyes is a painting about the kinds of forces that make the distance short between success and imminent disaster. And those forces are painted in paint that does not belie what it is. Like Cézanne the paint brush strokes are layered and have their own solidity and dynamism of multidirectional flow. The flow of a brush is not unlike the flow of the sea. Yet that flow comes and goes and criss-crosses in contradictory motion, with patches of stiller paint contrasting with it and creating a kind of unstable solidity. The layering of the rocks carry through paint a history of geological forces that resist and invite erosion at different rates. Cursiter shows this by the use of blue paint slashes on the rocks that meet the picture frame. The perspective of the looker is constantly queered, those fore fronted rocks pull us down from those at the top of the picture and supposedly at greater depth. In fact the depth illusion is hard to maintain.

The boat, it was named the Margaret, leaves a clear and apparently straight path in its wake, giving assurance of securing its destination through the mouth of the rocks on the viewer’s right. That assurance is, however, disrupted by the effect of the occupation of the mid and bottom right of the picture-frame by uneven and very painterly effects of sea colouration and relative motion. The colour contrasts here make the maw out to the sea less stable and promise disaster. On the right of the frame the viewer finds little rest and permanence on which to fee that the boat may not list to the sharp layered rocks.

Even on first seeing it, this painting felt to me one which veered between confident ambition, in Linklater as man and boatman, in the painter holding in his brush the right to determine the play of directional and physical forces, and the sensation in the viewer trying to reconcile the painting’s insistence on movement and stasis. The sensation for me, and in that very Futurist, is of the simultaneity of forces in the vortex to which the viewer’s eye is drawn. Yet that vortex seems to shift position.

This makes me look again at Cursiter. At his interest in surf in particular or of unlikely shapes that have permanence whilst looking threatened (The Old Man of Hoy 1957) or full of alluring danger where depth perspectives shift (An Island Farm, Stronsay 1954) and Hoy and the Entrance to Scapa (undated) and the myth-filled Selkies Hellier, home of the seals (c.1955), a ‘selkie’ having the local reputation of Homer’s Sirens. This is another topic but I also feel it in the playful way he shifts the roles of his main female models in his paintings – his wife Phyllis and main model, Peggy Low. In House of Cards (1924) an apparent unflappable woman modelled on Phyllis watches another, the later in a kind of dressing gown, precariously mount towards failure and destruction a pack of cards into a house or tower. It is fearful to watch and oozes direful imminence that is someone’s fear of failure.

But I want to finish by returning to whence I started, the Futurist paintings. If we look again at The Sensation of Crossing the Street – The West End Edinburgh 1913 we might find it more fulfilling if we see in it that its business is not emotion free, The flows of pedestrians have a simultaneity that does match the fearful as well as the confident crossings of streets in busy cities, We may catch the impression of a beautiful face, but its green shadows predict the movement of the tram behind and above the face, which has already moved behind her, when we see its passengers on the right of her. People appear, as they do when caught in the travelling eye of pedestrians, to collide or appear to be doing so. It may even be that a collision with a bus is possible.

Similarly in my favourite Rain on Princes Street (1913), rain and light takes the form of a solid military bombardment, with something of the burst of Vorticism present. The fantastical animals on the lampposts appear to come alive and threaten the faces that appear in the separate frames of the umbrellas, which are variously missing. Two male faces to the right seem to ponder disaster, in one the eyes are merely dark holes.

Now my feeling is that Cursiter is forever painting that flow between ambition and its quenching by natural or human forces, that fight with a kind of randomness. As he settled in as Director of the Scottish National Gallery he may have felt that in the end he embraced the assuredness of settled contemporary reputation that represented in fact what he had feared to be the death of his reputation as an artist. I wonder. perhaps there is greatness in that theme alone when you realise it as Cursiter did in excellent paintings about imminence of failure.

Steve

[1] Cursiter 1966 cited Beasant (2007: 90)

[2] Firth, N. (2007: 115) ‘The Summer for Orkney – Yesnaby’ in Beasant op. cit. 111 – 116.

[3] Cited quotations from Beasant, op.cit: 63.