Reflecting for a third time on Somerled @Somerled_Art: After Somerled began to work with digital animation of their images and to practice shape-shifting or metamorphosis in real time.

What does it mean for shapes to shift? I’d like to think it’s something more than one thing changing into another thing. If A becomes B that is not so interesting. But if A or something within it remains in some way constant whilst both acquiring new properties and losing others, this is interesting because it proposes that change and endurance have something in common – a principle that ties the series of transformations or its processes together.

A series from A1…… to A∞ – 1, for instance, will propose that characteristics, forms, and features are not ever in themselves the meaning of A. A is something else than the forms in which we know it. I feel something of this sort when watching the new digital art of Somerled – in which images of interiors, faces, exterior landscape or architectures change into each other, and sometimes back again, whilst the visual effect pivots on one constant feature. That is so, even if the constant is, for instance, a network of veins whether near from or deep under the surface of the skin. See examples of these on Instagram by clicking here. This is easiest to see in faces (I’ve tried to say something about Somerled’s faces (click here to see it)).

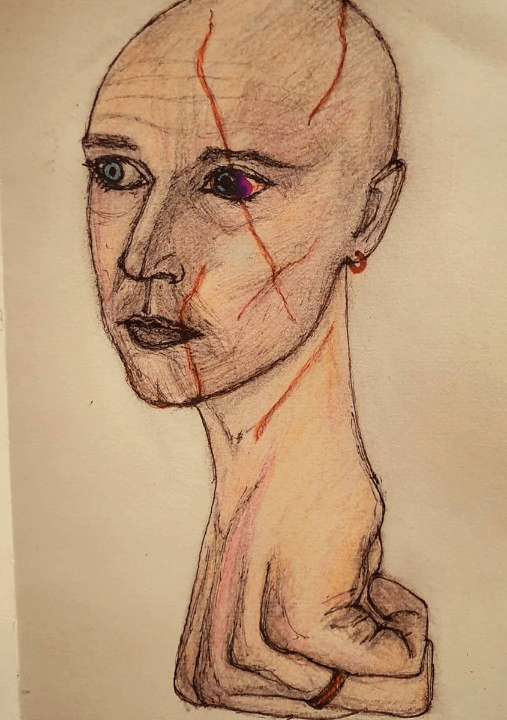

There is no change I think in these morphed images that does not employ a temporary constant to make the link. This might be an eye about which the a face’s morphology changes until an altogether different shape arises around it – sometimes with the addition of other features. An eye from a pair of eyes may become the third eye of another picture (a feature I reflected on in the past – click here). The use of features that in sometimes offer different kinds of portal between the inside and the outside of the body form the majority.

I include eyes in that because they are visceral matter that permits the entrance of external phenomena for internal processing and through which, if in ideal form, imagined forms can be projected onto the external world.

Indeed the whole process of what psychology calls normal visual perception involves what we might call ‘bottom-up processes’, where data from the world is taken in and dealt with, and ‘top-down processes’. In the latter, the brain draws from internal stores and data manipulations in order to identify what we are seeing. These internal factors are usually called, for instance: memory, mental manipulations, or emotionally defensive operations.

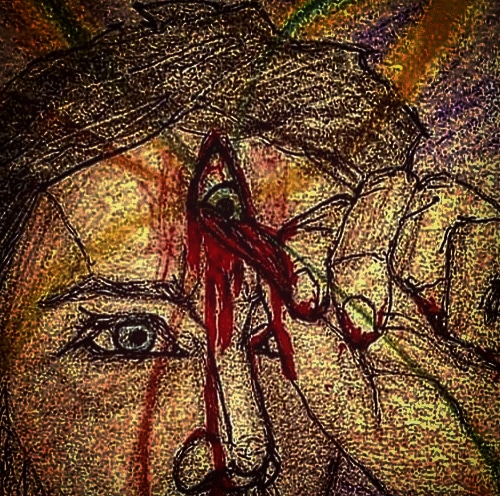

A third-eye is moreover a wound that turns into an eye and reveals the secrets that two eyes hide in order to allow human beings to think perception is only a direct bottom-up process and not one that involves internal processes. Only when such processes act abnormally, it is sometimes thought, do they blur images as well as focus them, shift their shapes, into what we call distortions, as well as make them match prototypes. Yet all of this blending of processes happens in Somerled’s art.

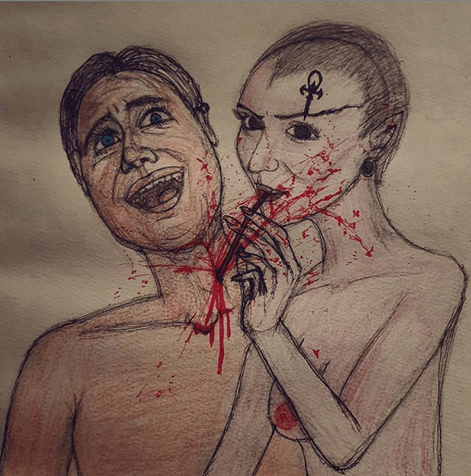

Other facial portals used are more straightforward or at least apparently so. They are facial orifices; other cusps between what remains, and is kept outside, and what returns from within to the external world. Mouths, for instance can be the focus of change and that change involve teeth shape and relative forms of introjection that move from easy absorption to violent destruction through teeth of the incoming object. Ears and noses contain other orifices sometimes employed.

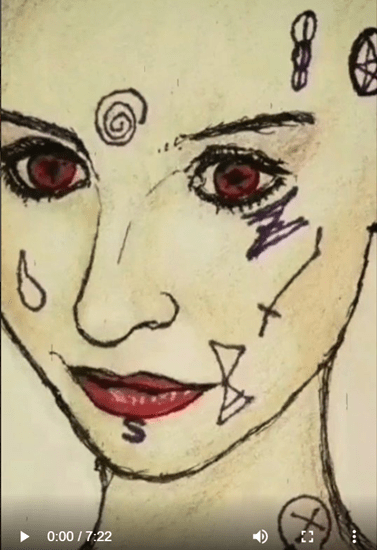

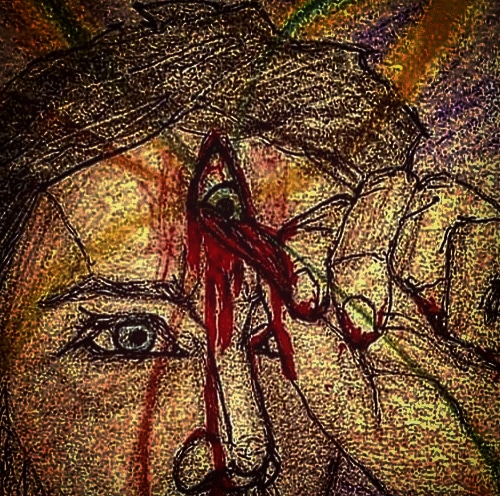

But the characteristic of a sequence from this art will be the compulsion to introduce new portals between the outside and inside of the mind-body or body-mind. These will be wounds of varying sophistication or artifice, such as tattoos which, in themselves mime portal eyes or mouths or even other lower body orifices or projectiles. They all form cuts or punctures – at times these will be heavily overinterpreted by these of the Christian crucifixion model and specific stigmata, others will be in fantasy, such as that of the vampire or succubus, or their ‘ordinary forms’ in murder and suicide.

When these are involved the flow between images is in the form of an apparent cut or splice in the film surface that sometimes verges through the use of colour transformations. In these (as in the example below) lines on a face become flows of blood from orifices, or wounds. The iconography of what we are trained to call self-harm in the West is as important here as forms of body decoration in subcultures (or ‘othered’ cultures). Sometimes blood pools though into a single image or its background.

Within all of these transformations lies the constancy in imagination which unites dead and live flesh, dried and died blood and fluid. Even tears are excreted and form shapes or offer an iconic form for expression, in a tattoo or jewelled image, that may or may not be emotional in its content.

We see things we can’t understand in the changes rung in art. They cannot occur unless we drop ‘common-sense’ distinctions between mimetic and fantasy images. The cutting teeth of Dracula are as real as the mouth of a superstar. Somerled often allows transformations from drawn to photographic images of ‘real’ persons to show this necessary process of entering a liminal world between inside and outside, subjective and objective, fantastic and realistic. It is not only that drawn images are artistically manipulated but that real ones are already pre-manipulated – whether by make-up, body art (or purposeful or accidental cutting) where the difference between dead and live matter, as in hair (including brow and lash hair) and make-up again make for unexpected changes in colouration or shape.

And it does not stop there because Somerled faces can utilise a wrinkle to cut or erupt into the cracks in the walls of an interior space and impel process of hurt, accident, decay – intentional or through neglect. These confuse our grasp of what is interior and exterior. Hence buildings or objects are often an image that might be produced from as a face morphs or vice-versa. And then the relation of foreground and background might play over ones of inside and outside. Sometimes heads and faces proliferate or grow from each other. This can be set in static images or be the illusion formed just within the digital transformation of image to image.

Of course I am recalling many digital presentations I’ve seen here. What if we look at one. For a single example of transformations look at this video which starts with an emaciated splintered face that seems to grow outwards in an effect that looks in part like a fattening of the face, inducing changes as it goes by splitting, cutting that involves changes of perceived age and gender – and of the display rules of body hair. Sometimes a face is reduced to chiaroscuro that can look like the cartography of island shores or mountains before vision resolves it back to face. It can be dead and flesh-less. It can associate with known facial images and then not. And the music queers all this. Sometimes the cuts and scratches fill only a background or at other times they cut over the cusp that is the boundary of the face’s form.

I realise here the superficiality of any comment on very living art.

STEVE