Reflecting on queer puzzles in Cavafy. Based mainly on reading Cavafy, C.P. (trans Daniel Mendelsohn) (2013) C.P. Cavafy: Complete Poems London, Harper Press & Liddell, R. (1974) Cavafy: A Critical Biography London, Gerald Duckworth & Co. Ltd.

Mendelsohn in 2013 tells us that Liddell’s biography, ‘is still the only book-length biography of the poet in English’.[1] When I looked for one this year I still could not find one, at least in current print, so I purchased Liddell online and read it with growing satisfaction. But far from seeing it characterised as ‘workmanlike’ by Mendelsohn, I felt it characterised the scholarship of another age, the very one in which I first went to university.

Liddell, like most scholars of his time assumes a readership more equipped with knowledge and experience than is usual now – hence quotations in European languages largely remain in those languages without translation, even in the footnotes. This has the beautiful effect in the case of Cavafy of reminding us of the cosmopolitan play of Western languages in the cultivated and powerful across Europe, Northern Africa and the Middle East that was certainly illustrated by him and his family. The family had fallen into genteel economies after the fall of their once famous trading-based status, but remained as familiar with the political and trading Levant as of Egypt.

As Greeks they traced their cultural heritage from Alexander’s creation of a ‘world’ Empire to the later Graeco-Roman ‘Hellenic’ Empire of the East and thenceforth Byzantium. Those Greeks of the Eastern Empire called themselves ‘Romans’ up to the fall of Mystra. Cavafy himself wrote in English and French with equal facility and was familiar with their literatures – his early Greek brief ‘epics’ often showing telling and not often culturally healthy influence of Tennyson’s narrative poems. Knowledge of languages is matched with assumed acquaintance with world literature. This too is respected in Liddell’s assumptions about his audience. On p. 84, for instance, Liddell quotes the final lines of Tennyson’s Enoch Arden to characterise the status of a Cavafy relative’s funeral without saying explicitly that he is doing so.

However, scholarship of that period was also often shamelessly personalised in its attacks on the errors of past critics – the acme of such behaviour being that of F.R. Leavis. Liddell is merciless in his treatment of Greek scholars whether their different thoughts concern Cavafy’s Hellenist politics, details of his working career in Alexandria under British occupation or his attitude to his own sexuality. Whilst these kinds of personalised arguments can be tedious in other contemporaneous scholarship, Liddell wins me over because his scholarship is used to attack the notion that Cavafy’s early poetry was self-oppressive, heteronormative and homophobic. Of course in the 1970s the critique would not be in those terms. Liddell shows that were based on a very lazy equation of a prejudicial view of Cavafy’s life and his poetic craft.

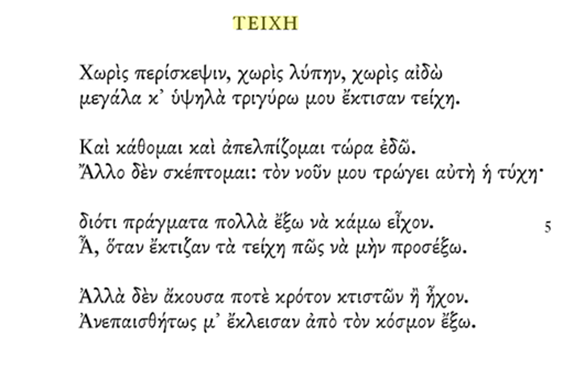

Thus Malanos’ view that the poem ‘Walls’ (TEIXH) written probably in 1896 according to Mendelsohn, contains ‘the cry of the homosexual trapped in his own temperament’ is comprehensively trashed.[2] Here is the original poem in Greek.

We need to see it in the Greek to understand that this early poem is both playful but also highly formal poem in its rhyme-structure. It concerns itself with very many ways in which persons feel trapped by the identity-constructions that are silently built around them by others; by ‘they’ not by the lyric ‘I’ itself. As Mendelsohn shows in his masterly Complete Poems, these early poems use conventional technique to show mastery in the use of sound to echo meaning.

Cavafy’s Greek with its full end rhymes has also a highly regular rhyme structure (ab, ab, cd, cd) as well as internal assonance to heighten the meaning in the last four lines. The poem’s rhythmic effects mime how a sense of imprisonment within oneself feels like an exclusion wherein the barrier walls shutting us off from others, usually external to the self, have been introjected. We sense them in how ‘noise’ that is usually thought to be an external stimulus echoes within ourselves. It happens in the rhymes partly: for example, in the rhyme between the past tense of the verb of possession (had) implying a world now lost “εϊχον” that echo-rhymes with the word for noise itself, “ἤ ἦχον”. These echoes Mendelsohn attempts to suggest with half-rhymes: ‘to do out there’, with ‘no noise … did I hear’.[3] If this attempt is only half adequate, it is much better than the total loss of echoes of meaning in the sound of the poem in Keeley and Sherard’s translation, with no rhymes at all:

…

because I had so much to do outside.

When they were building the walls, how could I not have noticed!

But I never heard the builders, not a sound.

Imperceptibly they’ve closed me off from the outside world.[4]

Hence the aptness and unadvertised appropriateness of Liddell’s comparison with the craft and seventeenth-century wit in George Herbert’s The Collar.[5] It may be that ‘Walls’, as Liddell shows, represents some kinds of repression of connectivity to life as it is lived. However nothing in the poem allows us you see it as entirely self-imposed or as specifically about sex, queer or otherwise.

This is important because contemporary queer readers are thrown off the track in looking for representations of a repressed gay male before the liberation of his feeling. That date of liberation is set by Liddell at about 1910. According to Liddell, before 1910 Cavafy really was a minor poet on the large obsessed with topics from the past of the Easter Roman Empire and Graecia Magna. Liddell also makes it clear Cavafy that became a great poet only once his celebration of class and sexual transgression could be treated as one with a deeper understanding of the flow of Greek history between sacred and profane values in both pagan and Christian orientations (at the time of the Emperor Julian for instance). His Greek historical poems, no less than what is considered his modern erotica, dramatise the life of the subjected ‘subject’ of a distant rule and power: with that power sometimes objectified in the ‘City’ of the Emperors and Empresses.

It isn’t only that Cavafy (in 1910 or whenever) came to terms with his own sexuality cognitively and emotionally (for he was almost certainly physically sexually active before then) but that he historicised and made stories of male-to-male desire that made the boundary ‘walls’ between inner and outer worlds less solid, or more porous at the least.

Liddell endures as a biographer I believe because, ‘workmanlike’ (in Mendelsohn’s word) or not, he defends the central importance of Cavafy as a poet who consciously avoided a large audience in order to maintain a slanted and queer vision of the world rather than one of the norms and phobias that maintain rigid conventions. For Liddell this is related to a transformation that occurred sometime near 1910-11 but was prepared for in articles such as that on Independence in 1907.[6]

The writer who has in view the certainty, or at least the probability of selling all his edition, … there will be moments when knowing how the public thinks and what it likes and what it will buy, he will make some sacrifices – … And there is nothing more destructive for Art … than that this bit should be differently phrased or that bit omitted.[7]

Liddell’s attack on what we now see as Malanos’ homophobic readings of Cavafy is at its best when he examines how queer sexuality and history interact in the cognitive world of the scholarly Cavafy. According to Malanos, Cavafy ‘made his perversion travel through history’ by using history as a ‘museum of safe and useful masks’.[8] The view that love, desire, and confirmed relationships between men, is new to history or confined to the limits set by the invention of the twentieth century term ‘homosexual’ is a common enough one; despite the fact that it denies nearly all the multicultural evidence otherwise.

Cavafy’s historical narratives demand that this view be suspended. Instead we turn to his treatment of situations related to the role of sexual attraction across class, status and its interaction with nascent exchange economies. This is Cavafy’s constant subject as examined by Liddell in extraordinary frankness. Such trading economies spanned those of the trading cities to the sale of one’s body to finance life, or a life more embellished and decorated with things.

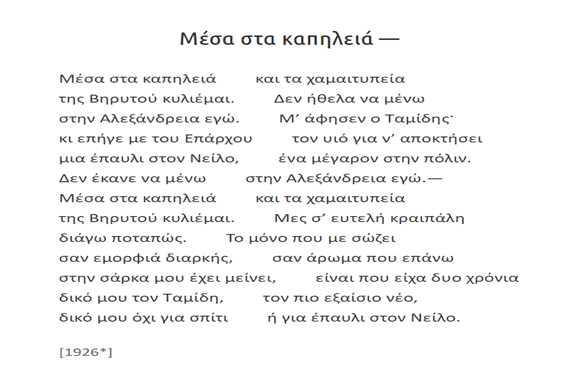

The presence of coins in his poems is not accidental or a sign of numismatic eccentricity but of another deeper queerness. He moved across time and space with the fluidity of the forms into which Greek political life metamorphosised from fifth century BC Greece through to the Alexandria under the Greek Ptolemaic dynasties to the fall of the Christian house of Comnenus in Trebizond in the fifteenth century AD. The geography covers the Levant coat, the cities of Sidon, Tyre, Beirut and Semi-Christian Antioch, as well as Alexandria and Constantinople. This made his range of selection of class typologies huge, more so in that he (in line with the interesting class lineage of Byzantine royal families and historians, including Anna Comnenus). He chose to focus often, even in the poems of more ancient history (but even too of near history), on characters from the lower the very ‘lowest’ classes of society in his repertoire of host cities. A poem that celebrates that spread in historical time, geography and class is ΜΕΣΑ ΣΤΑ ΚΑΠΗΛΕΙΑ, or In the Taverns, probably written in 1926.

I cite the poem in Greek here because Greek readers, should there be any, may be able to correct my perceptions about the poem’s use of language, as I mainly exemplify it from translations. This is because my own acquaintance with modern Greek language has barely the depth to yield enough surface in order to be called superficial. However as with the poem TEIXH, certain intended effects are clear even to that knowledge. A feature of the apparent form, that which is visible from the surface organisation of units of language on the page, are the lines split by spaces, a feature more lavishly and purposively used by Andrew Macmillan. In Cavafy’s use the space also indicates a much more obvious regularity of appearance that is almost conventional, a kind of ‘caesura’.

Indeed so much is this the case that Keeley and Sherrard translate the spaces sometimes, but not always, as full line breaks. They sometimes drop the internal line break without substitution to produce a full line of 14 syllables. Of Cavafy’s poem in Greek they say in a note of this and other instances, where he follows a similar practice: ‘Each line consists of two lines varying from 6 to 7 syllables’.[9]

This assumption that Cavafy used spaces merely as another way of dividing units which some translators treat as distinct line of poetry should be thought as a radical transformation of the poem. It is not an assumption made by Mendelsohn as a translator, who preserves the spaces as distinct from line breaks. So free are Keeley and Sherrard of their assumption about how and why Cavafy, in their view, used lines as the primary unit of meanings, their translation is even freer about how to break lines or not. The first repeated line of their translation has 14 syllables and is not space-divided.

I think we can justify Mendelsohn as much nearer to Cavafy’s practice, and perhaps intention, but it’s worth seeing why the earlier translators might have done as they did. My hypothesis is that for them it emphasised Cavafy’s exact repetition in the poem (in lines 1f. and 7f.) of the lines in the original about Beirut (Βηρυτού)

Μέσα στα καπηλειά και τα χμαιτυπεία

της Βηρυτού κυλιέμαι.

We can compare how these lines are treated in the two earlier translations and in Mendelsohn:

| Mavrogodato (1951) lls. 1-3 & 13-15) | |

| Down in the taverns And in the bordellos Of Beirut I wallow. | |

| Keeley & Sherrard (1975) (l. 1 & 7) | |

| I wallow in the tavernas and brothels of Beirut. | |

| Mendelsohn (2013) (ll. 1f., 7f.) | |

| In the public houses and in the lowest dives Of Beirut I wallow. |

All translations use exact repetitions at this point. It has its strongest effect in Mavrogadato (given he uses three repeated short lines) and the weakest, in my view, in Keeley and Sherrard where the whole unit for repetition is resolved into one line. Mendelsohn’s version is superior not only in that it respects the formal choices made by Cavafy but that it preserves the placement of the verb to the end, ensuring that the inactivity in that grammatically active verb is emphasised to English ears, which, unlike Greek ears, would not expect that order in the syntax.

My response is that the English insistence on lyric ‘I’ in poems as a reflection of our grammar is too insistent in the 1975 translation . It gives too much weight to the activity and decision of the poem’s narrator. The effect is a highly contrived one, where the lack of any poetic economy in the expression of ideas or (in)actions is doubly emphasised by the repetition. I prefer Mendelsohn’s solution to Mavrogadato’s because, although it shares that delayed verb, its short lines have a jaunty rhythm rather than the exhausted feel in Mendelsohn. I sense and believe that Cavafy, where the internal line break occurs, forces a catch of reflective or reactive breath rather than indicating a unit of isolated meaning that is associated with a full line. Better too because Mendelsohn chooses not to archaise, exoticize (or orientalise) the places it names. He has public houses and dives not tavernas and bordellos.

If Mendelsohn is correct to emphasise the innovative formal and the traditional qualities of Cavafy’s form, I’d argue that this better serves meaning. Look for instances at the treatment of the near repetition which follows and precedes respectively the exact one discussed in the last paragraph and again compare treatments:

… Δεν ήθελα ο Ταμίδης (l. 2)

στην Αλεξάνδρεια εγώ. ….

…

Δεν έκανε να μένω στην Αλεξάνδρεια εγώ. (l.6.)

…

| Mavrogadato (1951) (lls. 4f & 11f.) | |

| I did not want to stay 4 In Alexandria, not I. … I would not stay in 11 Alexandria, not I. | |

| Keeley & Sherrard (1975) (l. 2f. & 6) | |

| I did not want to stay 4 In Alexandria …. It wouldn’t have been decent for me to stay in Alexandria 6 | |

| Mendelsohn (2013) (ll. 2f., 6) | |

| … I didn’t want to stay 2 In Alexandria: not I. … …. It wouldn’t do for me to stay in Alexandria 6 |

It is not just that Mendelsohn preserves the literal delineation and its style that makes this half-repetition successful. The element in Greek in these lines that is word-for-word (στην Αλεξάνδρεια εγώ) in the original remains so, even if Mendelsohn must hang the repetition over two lines. Such changes are inevitable given the differences between the languages.

Likewise, although Mendelsohn uses (with better punctuation for the proposed meaning which reflects back on the speaker’s self-estimation) Mavrogrodato’s ‘not I’ to account for the emphasis given in Greek by its otherwise otiose use of εγώ, he finds ways of showing that it is the speaker of the poem who is emphasising his own egotism. This is so even if his egotism is of a passive rather than active kind, an unchallenged assumption of his own self-importance. After all, he gives Tamides, his lover, up, just as much as he is given up by Tamides for the sake of the ruling-class lifestyle of the Eparch’s son, with its villas and palaces in an ancient capital. My own reading of this poem is that Cavafy rather despises the ‘let-him-go’ attitude of the unnamed speaker.

I would argue that this poem is about the dangers of a passive attitude to time as it passes, that manifests itself in the linguistic register of this poem’s speaking character. Self-centredly aware of what would ‘do for me’ the fact that he what actually ‘does’ for himself is to live a life so inactive he will ‘wallow’ and ‘spend his sordid hours’ only in what is ‘low’ and of unredeemable value.[10] He is a kind of inverted snob, just as we suspect Tamides’ new lover might be a ‘real’ snob.

I use the term ‘unredeemable’ purposively since the speaker does find something that ‘saves me’. That is something from the past: emotional, and sensual capital that he lives upon now in the present. Cavafy often speaks of the remembrance of past physical contact enduring for the person who experienced it as if memory were itself a thing embodied in the skin sensations and bodily organs that made it. Here, however, the speaker is constantly obsessing on something relatively recent that is only like, a simile of, ‘lasting beauty’ rather than an enduring symbol.

That is to say that the speaker in this poem shows in several ways that he is wasting time, whether that time be measured in years, hours, ages of a civilisation or of that most fleet of things: the beauty of youth. And that is so whether the ‘most exquisite youth’ in this poem is that embodied in Tamides or that in the speaker himself. Sometimes Cavafy speaks of remembering a delicious male youth in his poems that might turn out to be a memory of himself.

We forget that poetry allows of ambiguity and that in the following more than the one meaning of a complex word with lots of ‘history’ can be at play, even when the context seems to limit it. The ability to find meanings referring to time from abstract (time / ages) to specific (years often but not necessarily) and even the tenses of verbs persist in the Greek term χρόνια, even the name of Chronos himself, the father of all being.[11]

… είναι που είχα δυο χρόνια

And what redeems time is what lasts: εμορφια διαρκής (lasting beauty) for instance. We get near to the queer metaphysic of Cavafy here. For what gives value, and the ability to endure in time is the active touch of flesh on flesh, something like sexual incarnation understand as a relational matter. This is not a person but touch between person and person, a kind of homo-sensuous-ness (to coin a term), never solely owned by any human persona but a quality of human bodies touching in the presence of desire. It is what gives the deliberately anonymous speaker value, it is (rather than a life of palaces and villas) what gives Tamides’ value. It is the deep motive power of history. The most beautiful lines here are rendered very differently in our translations:

| Mavrogadato (1951) (lls. 20 – 24.) | |

| Like a fragrance that over 20 My flesh has remained, Is that for two years I had Tamides for my own, | |

| Keeley & Sherrard (1975) (lls. 10-12) | |

| …., like perfume 4 That goes on clinging to my flesh, is this: Tamides, Most exquisite of young men, was mine for two years, | |

| Mendelsohn (2013) (ll. 10-12) | |

| … like a perfume that 10 Has stayed on my flesh, is that, for two years, Tamides was all mine, the most exquisite youth,…. |

Again Mendelsohn allows us access to the fact that youth is an abstract term in this poem, whilst the other translators literalise it as referring only to the persona of young Tamides. And even though the physicality of the 1975 translation’s ‘clinging’ to describe both flesh and perfume shocks me with its appropriateness, I prefer Mendelsohn’s quiet and more possessive personal agency of ‘stayed’. Of course that may be because it matches my reading. What in the two boys was the same: young desire or desire for youth (remembering that Cavafy often fixes that age for men in their twenties, ideally 23-24) is what gives time meaning and significance. It is the sameness of my term homo-sensuous-ness.

I sense that what this poem illustrates most of all is that any manifestation of Time, even the retelling of global histories, may make the same mistake as Tamides. The significance of history might only seem to lie in ‘things’, like villas and palaces, capital cities, or in passive living on capital from its past, such as is the memory of Tamides’ to the speaker here. In many other poems, Cavafy focuses on unknown young men who have not and will not make a name in history. In others he can begin in a poem to make you feel he is describing any attractive youth and then surprise the reader by showing that boy to have global significance, in the case of Gemistus Pletho for instance. The royal family member and historian of the ‘born in the purple’, Anna Comnenus, likewise can turn out to be a rather trivial power-seeker.

Our poem moreover has a probably purposive lack of specific historical placement. Some translators try to take that away. For instance Keeley and Sherrard translate the literal term ‘Eparch’ into ‘Prefect’ to indicate that this poem is set in the pre-Christian Roman Empire.[12] Mendelsohn keeps the Greek term ‘Eparch’ and says – unhelpfully – that the ‘milieu of the poem is the cosmopolitan ancient Levant’. Certainly, this poem gives no notice to Christianity or its values (unlike multiple other poems set in this changing milieu), although the Byzantine Church was to use the term Eparchy to distinguish its administration districts too. What is meant of the time of the poem is probably the ἐπαρχότης τῶν πραιτωρίων to show the origin of both terms in Roman administration, whose bounds can be seen in the map below:

The term ‘eparch’ is helpfully described in the footnote below from Wikipedia.[13] I’ve gone to (possibly unnecessary) lengths to establish a historico-goeographical milieu not to pretend certainty of knowledge in the academic mode but to demonstrate that, even for Greek readers, these milieu throw up divergent associations between land, peoples, politics and human value that cross the cognitive time-space barriers which assert that ‘history’ is a merely linear sequence. Because the focus here, and in the vast majority of poems set in any period of Levantine history, is on imagined persons from largely unrepresented classes in written history.[14]

The class of the young men in his poems but certainly here is not necessarily that of a working class, as it often is in the poems set in the twentieth century, but of any male who, without established income, parental financial support or expectations from their death, seeks to establish himself financially or does nothing. Liddell shows that even in in 1908, Cavafy’s attraction to ‘poor young men’, those he had sex with and which became his poetry, was in part an attitude to social themes that those men symbolised – a resistance to living, without work and bodily movement, on one’s capital, consuming not improving the riches of the past:

… the beauty of the people, of poor young men. Servants, workmen, small employees and shop assistants. One might call it a compensation for all they lack. All that work and movement makes their bodies light and symmetrical. … It’s a contrast with rich young men who are sick and psychologically dirty, …it is as if their swollen and emaciated faces revealed the ugliness of the theft and robbery of their heritage and interest.[15]

It is as near as we get, Liddell argues, to political statement but it does richly equate the privileged and leisured with dirty minds and bodies, related to misappropriation of their financial and bodily resources by luxuries. Marinetti seemed to grasp that in calling Cavafy a ‘Futurist’, like himself: ‘you have universal ideas, you recreate old times perfectly and enchantingly in our own time;..’.[16] For Marinetti that became a source of an ultra-right-wing National Socialism, in Cavafy it was more an attitude to how the use of body is to make, not consume time that I have tried to illustrate in In the Taverns. The men in that poem will never make their youth develop itself in beauty, activity and agility of desire but will ‘wallow’.

Liddell shows us how Cavafy worked out a kind of independent attitude to the politics of art in his notes on Ruskin, which he read between September 1893 and 1896.[17] After reading Stones of Venice his only note on plastic arts is to take Ruskin to task: ‘condemnation of that kind of architectural ornamentation which “takes for its subject work” is absurd and unjustified’.[18] On a passage from A Joy for Ever, his note equates historical and economic actions, even more strongly than Ruskin, with the meaning of Time itself:

‘ When we say “Time” we mean ourselves. Most abstractions are simply our pseudonyms. it is superfluous to say “Time is scytheless and toothless”. We know it. We are time,’ Cavafy.[19]

What I take from this record of Cavafy’s extremely focused reading of Ruskin’s social and aesthetic thought is that his subject, at least after 1910, was not either poems about Greek history or poems about bodies that make contact and touch each other in small squalid rooms but about both of these things at the same time. And I think, in his own way, Liddell has already said that.

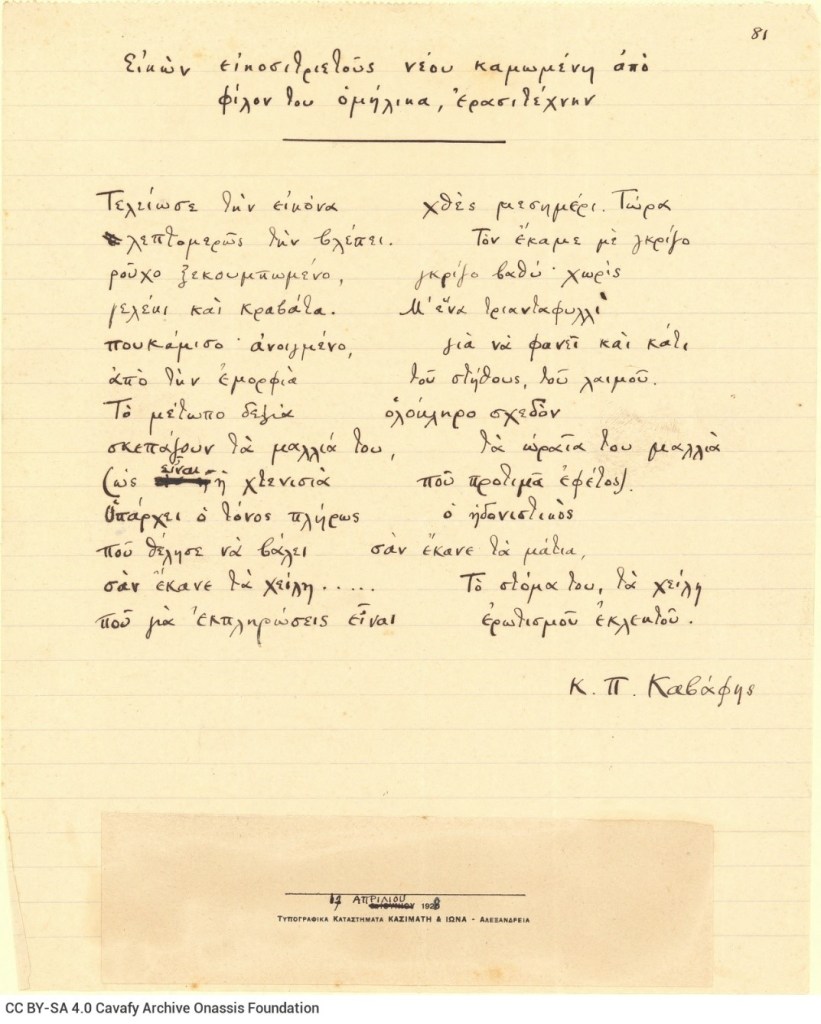

However, I want to end this piece by showing how Cavafy’s invention of a homo-sensuous-ness can illuminate the study of queer poetry by comparing another of his incomparable lyrics with one from Andrew Macmillan’s first volume, physical.[20] The two poems I have chosen are ΕΙΚΩΝ ΕΙΚΟΣΙΤΡΙΕΤΟΥΣ ΝΕΟΥ ΚΑΜΩΜΕΝΙΙ ΑΠΟ ΦΙΛΟΝ ΤΟΥ ΟΜΗΛΙΚΑ, ΕΡΑΣΙΤΕΧΝΗΝ (Portrait of a Young Man of Twenty-Three Done by His Friend of the Same Age, an Amateur) (1928) by Cavafy and Not Quite (2015?) by McMillan.

Εικών εικοσιτριετούς νέου καμωμένη

από φίλον του ομήλικα, ερασιτέχνηνΤελείωσε την εικόνα χθες μεσημέρι. Τώρα

λεπτομερώς την βλέπει. Τον έκαμε με γκρίζο

ρούχο ξεκουμπωμένο, γκρίζο βαθύ· χωρίς

γελέκι και κραβάτα. Μ’ ένα τριανταφυλλί

πουκάμισο· ανοιγμένο, για να φανεί και κάτι

από την εμορφιά του στήθους, του λαιμού.

Το μέτωπο δεξιά ολόκληρο σχεδόν

σκεπάζουν τα μαλλιά του, τα ωραία του μαλλιά

(ως είναι η χτενισιά που προτιμά εφέτος).

Υπάρχει ο τόνος πλήρως ο ηδονιστικός

που θέλησε να βάλει σαν έκανε τα μάτια,

σαν έκανε τα χείλη… Το στόμα του, τα χείλη

που για εκπληρώσεις είναι ερωτισμού εκλεκτού.

Κωνσταντίνος Π. Καβάφης

I’ve chosen this Cavafy poem because it uses the same long lines broken with space as In the Taverns. It also concerns two young men of the same age as that earlier poem, whose youth touches on each other. That touch is often nearly sublimed or hidden, by clothes but involves the trawl of eyes, sensual flow of sound to animate a visual impression, as if it moved, breathed and invited. The language is simple and the use of the ‘έκαμε’, which translates as ‘he makes’ as the artist not only acts to create the man but, as is emphasised in many translations, ‘does’ him at the same time. Although I feel I cannot argue this in detail here, the poem thus mimes the relation of artist to model, to his own projected youth and to the act of sexual fulfilment, the act of ερωτισμού εκλεκτού (Mendelsohn’s ‘choice eroticism, or in Mavrogodata’s term, ‘Exquisite lovemaking’).[21]

In this context the breaks in lines read for me less as empty spaces but as spaces filled with breathing or temporal shifts, particularly as the body of the young man is simultaneously dressed and undressed or when the register turns from a gaze that is appreciative and aesthetic to one that is totally sensual and ηδονιστικός (hedonistic). Space helps us to render the beauty of the body a matter of response in the reader’s body rather than merely at the eyes:

when he did the lips … That mouth of his, the lips

made for fulfilment of a choice eroticism

It is such that the reader must lend their body to its fulfilment (the term in Greek, εκπληρώσεις , transliterates as ekpliróseis) in mouthing its syllables and feeling for the appropriate spacing as a reading response. My main point is that a truly queer poetry will never individualise a body but proliferate it as a effect of multiple senses and complex interacting responses. Hence Cavafy’s sexual poetry is often described as ‘impersonal’ but if it is so, it is only so in that the feel of the body overtakes any search for individuating detail. The lover feels in fulfilling the erotic not only someone’s body but also their own, and perhaps multiple other bodies that have trained the fleshly contact.

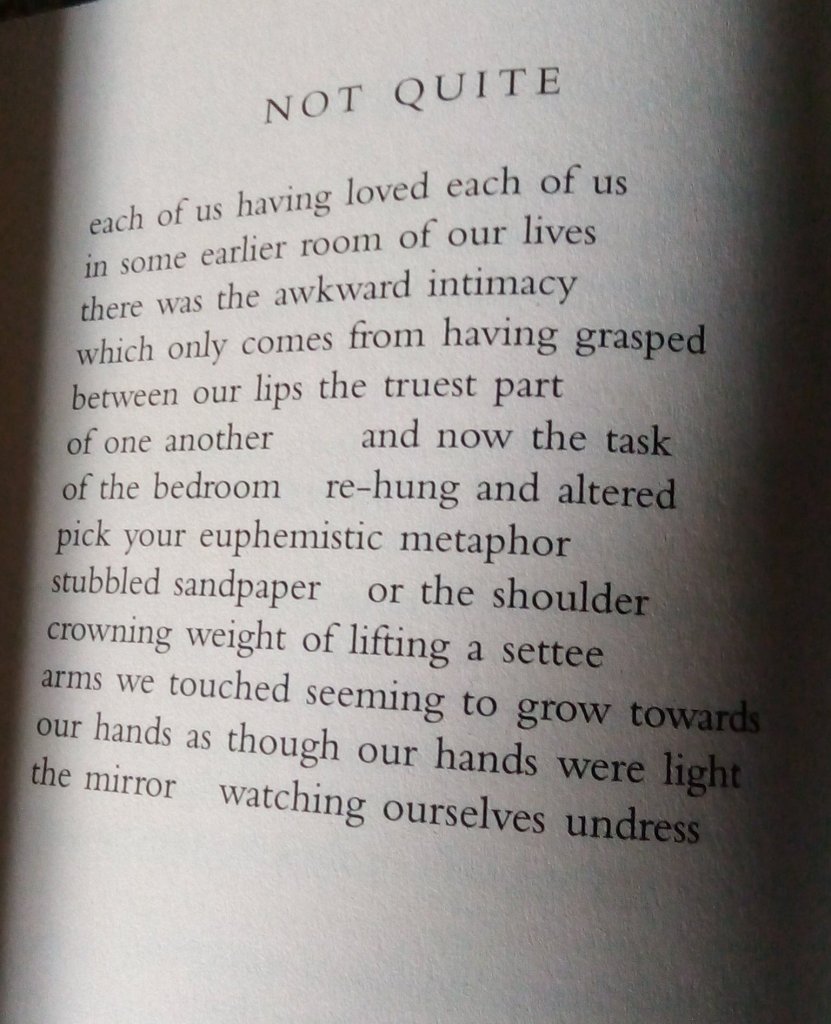

Andrew McMillan may or may not have studied Cavafy. Many of his effects can also be seen be influenced by his favourite poets as he grew up, such as Walt Whitman and Thom Gunn: those that spoke to his discovery and acceptance of a queer bodies and the interaction of queer bodies. Not quite feels to me a poem in the same queer chosen family as Cavafy’s. There are even better Cavafy examples to illustrate this without any implication that McMillan’s are at all dependent on them.

This poem in my reading posits a physical lovemaking that is described in two very discordant contexts. One is that in which lovemaking is learned and recorded in the memory traces of past physical experiences that are sexual or not quite sexual such as feel of sandpaper being like your male lover’s stubble or even how moving furniture recalls certain physical strains in that mental lovemaking. The second is that of using the masculine do-it-yourself task of physically changing the look and feel of a bedroom. These contexts cannot be separated. The second largely offers metaphors for the first, as we’ve seen in the activity of sandpapering and moving heavy furniture.

This mixture of concern with rooms as the locus of sexual congress and the body is even more prominent in more famous and accessible poems than the one I’ve chosen. But both use a legitimate way in which men ‘make’ each other and buffer each other’s masculine physical image to queer male-to-male contact.

The sense of the physical body and what is cognitive or a matter of feeling continual meet and cross each other’s boundaries. For instance consider the end of the poem in which I half imagine two men trying to compass in their arms a heavy settee. Yet in doing the poem almost sexualises the contact of their bodies, if only here extremities of the body:

arms we touched seeming to grow towards (l.11)

our hands as though our hands were light

It is because we do not know here whether these arms are of a settee they’re lifting or their own in cognition that they can become ‘light’, not heavy like the settee. And the final line, which catches sight of the same light in the visual sense in the bedroom’s mirror, imagines the full revelation of these men of their bodies to each other:

the mirror watching ourselves undress

There is in this much that is our Cavafy poem also:

…. He did him in gray (l. 2)

jacket, all unbuttoned, a deep gray. Without

any vest or tie. In a shirt of rose;

so little of the beauty of the chest,

the beauty of the throat, might show through a bit

Here I’d argue that both poets play with the dressed that is, at the same time, the act of being actively undressed in, and by, each other’s gaze, as imagined by one of them. And both poets refuse to individualise their male objects, who because of this can become the reader’s own awareness of their body, felt in ‘awkward intimacy’ and being ‘grasped’ as if physically in the cognitions recognition of its companionship with the body and affect. If anything characterises this making physical it is the fact of the broken lines. McMillan uses them less regularly and with less formal regularity than Cavafy. This may offer McMillan greater local effects. I sense this kind of reading implied too by another poet-translator of Cavafy, who describes the luscious Half an Hour as:

a love poem about frustrated but nevertheless insistently passionate desire. That’s why much of its intensity is conveyed by the rhythm of its discourse, short bursts of pleading words, breath-stopping line breaks, etc.

George Economou interviewed by Randall Crouch. Crouch, R. (2020) Jacket Two Available in: https://jacket2.org/commentary/translating-cavafy-eros-memory-and-art

The break in the last line of Not Quite, after the words, ‘the mirror’, imagines and reflects that moment of shock in which the mirror sees one’s own desire both in its action and object and gives us pause. The same happens in Cavafy where the pause after ‘unbuttoned’ is meant to excite as an apparent description of how the love object is dressed becomes one of how that perception is a kind of undressing. In McMillan, the lack of individual specificity in the loved one, as written, makes the bedroom being altered in the poem important only in the training from other men, at other times in other rooms. And that is true too of how the body of each is known for each of them from their own past body contact with other bodies, ‘in some earlier room of our lives’. How like Cavafy is that metaphor. And how queer, and yet how more truly honest than sexual ideologies of the master bedroom.

Steve

[1] Mendelsohn (2013: 652)

[2] cited Liddell (1974: 63)

[3] Mendelsohn (2013: 191)

[4] p. 3., Savidis, G. (Ed.) [Keeley, E. & Sherrard, P. trans.] (1975) Collected Poems: C.P. Cavafy London, The Hogarth Press.

[5] cited ibid.

[6] He ‘places this point at about 1910’ ibid: 159.

[7] cited ibid: 143.

[8] cited ibid: 158.

[9] Savidis (op.cit.: 184) Note on ‘In the Tavernas’

[10] Mendelsohn (op.cit.: 134)

[11] Let’s use an online teacher of Greek for authority here:

- The masculine word ο χρόνος can mean “year”, “time” and “(grammatical) tense”. In the sense of “year”, it has an irregular neutral plural: τα χρόνια. In the sense of “grammatical tense”, its plural is regular: οι χρόνοι. In the (relatively rarely used) sense of “time”, it just is never used in the plural. It’s also the main word for “years of age”, “years old”, used in the genitive to indicate or ask for the age of someone or something.

- The feminine word η χρονιά only means “year”, and seems never to be used to mean “years of age”. It’s a regular feminine word. It seems to be used mostly in the expression καλή χρονιά!: “Happy New Year!”.

- The neuter word το έτος (plural τα έτη) can mean both “year” and “years of age”, “years old”. It’s a relatively common alternative to χρόνος when asking or indicating age: πόσων χρονών είσαι; or πόσων ετών είσαι;, or just to mean “year”.

So the three words are relatively synonymous to each other in that they all mean “year”, but they are all three used in slightly different ways and in slightly different contexts, with “χρονιά” being the most restricted in its use.

From: Re: Two small questions about some sentences by Christophe Grandsire-Koevoets – Friday, 17 July 2009, 06:12 AM

Available from: http://www.kypros.org/LearnGreek/mod/forum/discuss.php?d=3753

[12] Savidis (op.cit.: 100)

[13] Originally eparchy (ἐπαρχίᾱ, eparchia) was the Greek equivalent of the Latin term provincia, one of the districts of the Roman Empire. As such it was used, chiefly in the eastern parts of the Empire, to designate the Roman provinces. The term eparch (Greek: ἔπαρχος, eparchos) however, designating an eparchy’s governor, was most usually used to refer to the praetorian prefects (singular in Greek: ἔπαρχος τοῦ πραιτωρίου, “eparch of the praetorium”) in charge of the Empire’s praetorian prefectures, and to the Eparch of Constantinople, the city’s urban prefect. From https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eparchy

[14] Although Cavafy himself rightly insisted that Byzantine historians were not so fixated on privileged perspectives in political and world history as those in the Occident (Liddell op.cit: ).

[15] ibid: 93f.

[16] From a transcribed conversation with Cavafy cited ibid.: 204

[17] ibid: 116

[18] cited ibid: 117

[19] ibid: 118

[20] McMillan, A. (2015) physical London, Jonathan Cape

[21] Mendelsohn (op. cit.: 147), Mavrogodato (op. cit.: 170).

One thought on “Reflecting on queer puzzles in Cavafy. Reading Cavafy, C.P. (trans Daniel Mendelsohn) (2013) ‘C.P. Cavafy: Complete Poems’ & Liddell, R. (1974) ‘Cavafy: A Critical Biography’”