Does the paranoia of fantasy thrillers help us understand complex events in real life?: Examining Peter May (2020) Lockdown London, riverrun Quercus Editions Ltd.

Peter May wrote this book in the wake of the fear that spread the world over a possible bird flu pandemic in 2005. Written in 6 weeks, he tells us in his Foreword, book editors in the UK rejected it because it was ‘unrealistic and could never happen’.[1] Yet it was researched using credible science during the period in which avian flu was the expected source of a second pandemic to rival and overpass the 1918 pandemic which is still rather startlingly called ‘Spanish flu’.[2] May himself does not make this point but the vey name of the pandemic is built on paranoia, as if a nation that first experiences an infectious virus were actually the responsible cause of it.

Paranoia often influences us most when we try to understand things we do not in truth understand and lack, sometimes though a possibly innate psychological resistance, resources to research. It is not just a name for fear or anxiety however but of beliefs that name without evidence a particular cause of the fearful phenomenon. Even a world leader has tried to name the current Coronavirus pandemic ‘Chinese flu’, to feed off swelling fears of being overtaken by the foreign, alien or different that come to light in periods of widespread fear. At such times the continuing tendency for human beings to prefer the cognitive miser effects of attributing causes of the unexpected to ‘folklore’ beliefs to the complexity of the factors actually involved in the aetiologies of all things.

Thrillers tend to use conventional narrative structures whose outcome is the answer to the question ‘who-done it?’. These structures maintain the interest of reader, working best where there are many optional pathways to follow to a probable answer. However they also depend perhaps, if they are to satisfy the reader’s desire for some closure at the end, on there being a single answer. That single answer will in itself be based on folklore beliefs – most disaster movies (like Jaws or The Towering Inferno for example) end with the answer that this event was caused by some instance of greed or other self-interest that is thought to be endemic to systems, like capitalist or communist economic systems. It is likely that this is a pathway to a final cause readers will be imagined in Lockdown, even though it be, as most systems are, hidden under the dramatic interplay between characters and character-types. I wouldn’t want here to say, since so much of our joy is in this pursuit in the footsteps and through the eyes of different points of view in the characters in the novel.

Shouldn’t we view thrillers then as art that fails to help us to understand real catastrophe or even wishes to do so? Was it wise, we might ask, to publish this novel now because of similarities and prompts that recall Coronavirus and our response to it. Yet that is the economics of publishing books – the salience of an idea increases the sense of what ‘realism’ is and what can be imagined to happen.

Joe Sommerlad quotes May telling the story of his rejected 2005 Lockdown novel to him and of the events occurring when he represented it to an editor who suggested he exploit the theme of lockdown in a new novel:

“I told my publisher about it and my editor just about fell out of his chair. He read the entire book overnight and the next morning he said, ‘This is brilliant. We need to publish this now.’”

The writer describes himself as “extremely creeped out” by how similar the current crisis is to his treatment.

Sommerlad, J. (2020) ‘Coronavirus: Novel rejected for ‘extremely unrealistic’ portrayal of London in pandemic lockdown published 15 years later’ in The Independent (4th May 2020) Available at: https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/books/news/coronavirus-lockdown-novel-peter-may-books-thrillers-kindle-a9447181.html

We have to use the word ‘exploit’ here because what we see here is how parasitic are popular thrillers on the accessible at the time of publication of belief systems which yoke imaginary to what we judge as ‘real’ worlds. It almost asserts that the time and space of successful creation is felt to require the co-operation of a present-time audience and the more external forces that aid to construct worlds we think of as ‘believably real’. Yet is this ‘exploitative’ of an audience forced to fear in a world that no longer mirrors its deep assumptions? If it is, it isn’t a malign exploitation necessarily, I’d assert. The world felt physically strange to all of us as we were forced by reasonable accommodation to a new threat, law and fear to change our social behaviours and our relationship to assumed continuities of life – such as seeing friends or loved one, visiting shops, cinemas and theatres for pleasure or even to justify our need to feel ‘busy’, significant and needed in a world larger than our homes.

Reading Lockdown not only validates our sense that our imagination and the assumptions about living made strange by art co-operate in the production of worlds we call ‘real’, but also can help us to explore the multiplicity of possible responses to that ‘reality’ and its variants in different minds. So that even when we understand what caused the severity of the viral outbreak in this novel, we are also aware that we do not live merely in a world of known cause of a known effect but in one that is perceived in a myriad of ways and with the possibility of surprising change in our assumptions about people and their motivation.

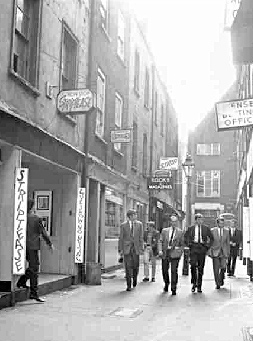

May knows that to find the events and people in a story engaging, in multiple ways, we need a setting that can be created for the reader, and which ideally reflects something we know or know about or believe in because of knowledge of the words which make it a known place. In this case, that place is London. It is the relatively static nature of London streets, sights and associations that hold he novel together, even as its characters traverse its known spaces. A place that is known or knowable allows for its estrangement – in the placing of street barriers staffed by the army, unknown uses of known architectures (as in Jonathan Flight’s South Kensington art studio), or the lockdown and curfew desertion of usually busy known places like St. Anne’s Court off Dean Street in clubland Soho.

We know exactly why, if we know London at all, and this is central tourist London, MacNeil, the policeman, fears that in this, ‘narrow pedestrian street between tall brick buildings’, that ‘he was going to lose him’.[3] Sense of place in some circumstances is all the more important when it is queered by the drivers of the fiction, that create the effect called by Freud ‘the uncanny’, where the familiar is de-familiarised and the known world estranged or queered:

MacNeil tilted his head gently back against the brick and breathed deeply. He felt something like hysteria slip slowly over him, like a shroud. Everything seemed somehow ought of control. His life, the city, his job, this investigation. It was if he were being swept along on a tide of events he was powerless to affect.[4]

There are moments, of course where we feel this rather than, as here, being told it – when following Amy home, for instance, where norms that have already been adjusted for her physical disability, are further queered, even by their unexpected and silent success and details of unexpected light and other ambient sensed phenomena in the restored Docklands, now gated communities.[5]

The lack of control, strictly true in this novel of hidden motives and near-Gothic activity taking place under apparently normal facades, of either building, faces or relationships for not only McNeil and Amy but a rather lovely and unusual, for a heterosexual male’s novel, gay couple, Peter and Harry. Harry is a kind of a hero, Peter who seems to being set-up as a stereotyped villain, is in the end just an ordinary and unheroic lover.

And this estrangement goes on to, if not in the actual villain of the piece but in the stage one. His back-story, gradually revealed makes his role in the novel believable, even if its final twist from psychopathy to empathy. And this is done, as is usual from a writer so literary in his interests as May even in popular novels, by making this man name himself Pinkie after the anti-hero of Greene’s Brighton Rock. An anti-hero who reads in order to further invent himself for us and open patent, almost Gothic-horror nastiness, into other possibilities of character-choice and self-determination is a lovely stroke in the novel, satisfying in interesting ways. And more than that we know, because we are told, that Pinkie has read Aldous Huxley, William Grassic Gibbon and Ernest Hemingway as well.[6]

Because thrillers may ask us to find the eventual one agent or cause of their story’s complications, but they don’t merely kill off the complications by embodying them in an arch-villain or Moriarty, a Communist plotter, a greedy capitalist fixing the market or suppressing facts. These live on in passages that show us how lives estranged, the sense of events beyond our, or any human control can be experienced, interpreted and re-interpreted.

The virus in this novel remains the true killer literally. Hence, it ends not with total resolution of matters but of a sense of continuing uncertainty and lack of control despite the fate of the person who caused all this mess by the most horrible and graphic cruelties described – and expected even from the ‘Prologue’ of the novel.

I am not a thriller reader normally but I have loved Peter May’s work and I’d claim this novel did make me more understanding of my own reactions to lockdown, whether potentially shameful, decent or middling ones. It showed the interaction of the uncanny as something that unites social circumstances with byways in our own psychology in groups or as individuals. Of course, the usual suspects arise – is it right to represent a disabled woman primarily as a victim, for instance? There are arguments against this position in the novel as well as for it.

But most of all, I think the novel does make itself open to a kind of reflexiveness. Once central character is a popular but arcane ‘artist’. McNeil is forced to investigate him over two visits which are extremely near to each other but which have different outcomes in terms of how we assess Flight as man and artist. On the first visit, we are deliberately though being asked to say what makes art acceptable or not, especially in terms of the manipulations of the human body it uses. Now this book is obsessive about how human bodies (bones, blood, flesh, hair and everything else) can be broken down and partially reassembled, even the body of the main female character, Amy. Hence I find this passage about the very ‘ordinary’ response of MacNeil to art really interesting:

… The arts column of the broadsheets had been full of him last year, and some of his work had been controversial enough to make the tabloids, where MacNeil had read about him. He specialised in the grotesque, often overtly sexual body sculpture. A headless man with his, often overtly sexual body sculpture. A headless man with his erect penis partially inserted in the anus of a female torso. A woman with one arm missing, holding her severed breast in her remaining hand. … MacNeil could not imagine who might buy stuff like that, or who would want it in their homes. But his exhibitions attracted thousands, and his work sold for tens of thousands.[7]

There may have been a model for such an artist in May’s mind but I’d venture to say that May’s art is not a million miles away, in the interests in both sex, murder and dismemberment, from, Flight’s: even if not in visual form but in words. Amy is an artist of sorts, reproducing bodies from evidence, the startling virologist Dr Castelli, an older woman with an amazing bodily and moral strength, reassembles tragic stories from the effluvia of bodies. Detectives, and the authors of thrillers who fetishise them, make their living from a grim interests of hopefully thousands who are hoped to find reading motivation from novels with passages like this near their opening:

…”What the hell’s that smell?”

“The bones,” A crinkle around the young pathologist’s eyes betrayed is amusement.

“I didn’t know bones smelled.”

“Oh, yeah. Two, even three months after death.”

“So this kid was alive quite recently?”

“Very recently, I’d say, from how much they stink.”

“so what’s happened to the flesh?”

“Someone’s stripped it off the bones. Using some pretty sharp cutting gear.” Tom lifted out a long-shanked bone, laying it delicately across both hands. …[8]

Tom, the pathologist here, is one of the gay characters, by the way. More relevant to our theme at this moment though is that there is a deliberate objectification of a girl child’s remains, handled and discussed by men, that feeds appetites for popular art not that different which feeds the art-audiences of the fictional Jonathan Flight in the novel. May’s novels research death and dismemberment as a matter of course and perhaps as a matter of the conventions of a detective thriller but manipulated bodies disabled of their own agency mark the sex in the novel too:

Amy lay on her back gazing up at the ceiling. Her right leg was raised and propped on MacNeil’s shoulder. He knelt in front of her and his big hands worked down the muscles of her calf, strong flat thumbs kneading giving flesh … She wished she could feel it. ….[9]

There is a deliberate analogy here of men who sculpt women’s bodies and perhaps their image as desirable like Jonathan Flight mentioned earlier in this piece. The reminder that Amy has lost all nervous sensation is complex because it renders Amy’s subjectivity for us without overly objectifying her as entirely the representative of a man’s desire. In fact Amy’s viewpoint is always more a matter of mind than MacNeil’s.

These manipulated bodies, shaped by inner desires and identities go throughout the novel and can easily be unnoticed. Let’s look at how the gay couple are introduced. Surely here, May is playing with folk beliefs about transsexuality and homosexuality that he mentions in order to subvert them through the story. It is Pinkie who makes an unreliable point of view for these perceptions and that is why we can know that is important that we realise that some narrators under-estimate the being of otherness they talk about:

The flat in Parfrey Street was opposite Charing Cross Hospital. Pinkie knew it had a reputation for amputations and sex changes – although not necessarily in that order. Before the pandemic, residents used to joke that they couldn’t tell if someone coming out of the hospital was a man or a woman. The perfect place, Pinkie thought, for the couple he intended to visit.

Tom and Harry’s flat at13A was just above a florist’s shop, ……

This is clever. Tom and Harry are gay men and the links made by Pinkie are Pinkie’s own, it is he, and perhaps the locals at Fulham that equate these categories. And yet they show how supposedly familiar landscapes, like this part of Fulham, are in part made up of assumptions that we might call social cognitions and which can be false.

This is why novels like this can help us. Feelings of loss and bereavement, and these are dealt with here in terms of acquired disability, loss of children to disease and even abuse, divorce or separation and of parents, like Pinkie’s mother and even, growing up and away from old love objects. These feelings are nearly always as Parkes tell us, of assumptive worlds, worlds that are really made up of assumed or habitual thoughts, sensations, or feelings. It is these we need help with and I’d say most reading helps us with this. However, this novel is about this.

Reading it is not to be exploited by a novelist or publisher, though we need to be aware perhaps of the economics of publishing, but also to be assisted to work through the losses that lockdown brings and open up the world, if you let it happen and not all people do, to new, or even forgotten old, ways of being seen and valued.

Now, as he sat on his bed his so would never sleep in again, he thought of hs (parents) for the first time without anger. Remembered things he had forgotten. Things from his childhood. Laughter, kindness, safety. … It was very Scottish, very Presbyterian. You could feel affection, but you mustn’t show it.[10]

I am, unlike Peter May, neither from a Presbyterian nor Scottish background, but this feels meaningful to me and healing.

Do read this novel. It is also very fast paced with a can’t put-down end if you find my approach to it unappealing.

Steve

[1] ‘Foreword’ in May (2020: p. x)

[2] He had researched this for his 2002 novel, one of the ‘China’ thrillers, Snakehead (ibid: ix)

[3] May (2020: 195)

[4] ibid: 202

[5] See, for instance, ibid: pp.63f.

[6] ibid: 58

[7] ibid: 203

[8] ibid: 25

[9] ibid: 75

[10] ibid: 114