NOTE BY BLOGGER: Sometimes a blog makes you query why you create blogs at all. This is the case here. I started with the view that there was a sub-textual message to the volume that promised a way of reviewing our queer lives. As I approached it’s end, I realised that the elegiac poems, although linked to these themes in some inarticulable way, for me at least, they couldn’t be reduced to it. Hence when I got to the end I realised more and more why Hewitt entitled his own comment on his poems: ‘I would give all my poems to have my father back’. Such statements are in fact irreducible. Some forms of individual love will not be reconciled with theory. So, since this blog is really for me, I’m letting those contradictions remain. They are my contradictions!

‘Our life is a theophany.[1] … Reflecting on Seán Hewitt’s (2020a) Tongues of Fire London, Jonathon Cape.

In a statement about this book, Hewitt summarises the connection in it of some key themes: the reflexive examination of the queer self, the body and what we might call ‘description of nature’:

When I took a step back, I realised I was joining the poetry of nature with the poetry of the body, and the queer poetry of the body in particular, and those seemed to be the two strands I was working with. ….

And then also life happened along the way, and so the shape of the collection changed as my life did….

Cited (p. 2 of 7) in The Nan Shepherd Prize Interview with Seán Hewitt available at: https://nanshepherdprize.com/resources/who-to-follow-and-what-to-read/interview-with-sean-hewitt/

It is obvious from this that whilst both themes (nature and the queer body) is explored throughout the book, the concern with the queer body is with a body that changes and develops in shape. This is not a matter of reproduction of a changing life in the facts of a biography but the creation of a literary autobiography, an autobiography that is subject to the shape-changing and metamorphic propensities of literary fiction. An easy way to indicate this simple fact is to show that the work in no way attempts to organise itself simply along the lines of the chronology of its poems production. We can never, of course, be certain of that order in any poet. For instance, the germ of Tennyson’s Maud appeared in 1835 and was his first response to Arthur Henry Hallam’s death in a love poem, well before its much later publication in 1855, five years after In Memoriam.

But, in relation to the art of Hewitt’s ordering of the poems, mentored in its craft as it must have been (and indeed he tells is it was), consider the relation of the placement of Sean Hewitt’s earliest published poems, from his collection Lantern, first published in 2019.[2] The published poems from Lantern are by no means the first poems of this collection, apart from the first three, which are. They are republished in that same order, though in some respects, explored by Juliano Zoffino, changed in some phrases.[3] Nine of those poems are in the first easily identified section of Tongues of Fire but not in order. Five are in the penultimate section preceding those reflecting on the death of the poet’s father, and again not in their original order in Lantern.

For my purposes, even more interesting are the two poems left out of Tongues of Fire, ‘And I will lay down …’ and Waterlily. [4] Both of these poems reflect what I would call socially ritual poems using a high degree of abstraction from religious discourse to evoke the spiritual. Although I think neither are of Hewitt’s best work, both may also have been left out because they would have been too early a revelation of the destination to which the poems reordering as literary biography was tending. For instance, ‘And I will lay down a votive to my silver birch’, is nature already slanted to the supernatural (including the association with ‘witches’ broom’ (l. 4.) and specifically to a ritual votive offering of self to a male deity via the mythological attributes of the silver birch. Even the capture of the deity by the masculine gender, given the feminine attributes it had in some of the mythologies, is dealt with as part of the somewhat camp humour of the poem

for he can pass as a woman (l. 28)

for often his skin takes the pink of dawn

This poem plays with a queer take on nature that ignores the anachronisms in its attribution of qualities between myth or forestry maintenance (‘the improver of soil quality’, l.20), such that contradiction of a binary kind – even across two lines of the poem merely does not matter:

for his body is an instrument of the wind (l. 23)

for he is pure and purifying

for he is vulnerable to fungal pathogens

I see the pagan hymnal quality of this as deliberately comic, just as the ‘wind’ that plays around the trees branches is, in its juxtaposition to the overwrought character of ‘pure and purifying’ takes on the bodily attribute of a fart, the ‘fungal pathogens’ to which the tree is subject a play on the confrontation of fungal pathogens experienced in sexual bodily contact sometimes. This tone is not largely those of the poems at the close of Tongues of Fire but it deals with the same relationship of the queer body to its supernatural penumbra in acts of worship. The description of what it means to give oneself to another is laden with metaphors of church worship: ‘choral evensong’, ‘holy fonts’, ‘liturgical time’, and ‘resurrection of the dead’.

Similarly the other rejected poem, Waterlily, is an extended conceit, such as we might find in George Herbert, of the plant to the concept of a church. It raises a hymnal repetition of ‘glory be’, ‘praise’ and seeks among the congregated multitude of its leaves on a pond’s surface, ‘its searching / root as the mystery of faith (l.11f.)’. It ends to with the concept of votive sacrifice.

It again has a modern as well as seventeenth century understanding of poetic ‘wit’, both as humour and overt cleverness in the extension of a base metaphor. My strong feeling is that both poems would have seemed false in tone, given the exploration of the leap into a deeper supernatural and a deeper sense of what deity (called just ‘God’) is after the experience of personal suffering, even though it is still a queer God, a God of the social, instead of just the individual, body of the queer. I’m taking the concept of a revelatory religion emergent from the collection and aggregation (I’m tempted to say ‘congregation’) of the poems much further than does Zoffino, in probably the first careful study of the body of the whole volume. He says that, onwards from the poem Adoration, :

There is a gradual move towards the Pentecostal, beginning there. As the poems move towards their end they acquire an increasingly acute taste of grief, as Hewitt’s “pre-elegies” for his father ask us to consider such things that we may never be able to fathom: “Are we all / just wanting to see ourselves / changed, made unearthly?” he asks in ‘Petition’, …

Zaffino, J. (2020) ‘Seán Hewitt’s Tongues of Fire’ Available at: https://severinelit.com/2020/04/28/sean-hewitts-tongues-of-fire/

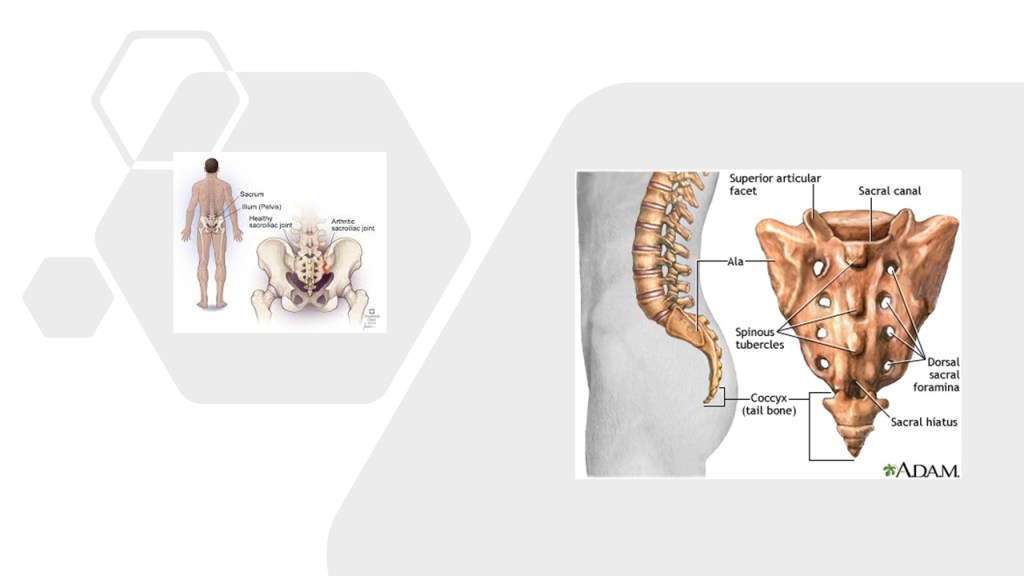

Where I differ from Zaffino, which is in matter of detail probably rather than in direction of a large part of the interpretation, is that I see the concern with ritual diving ‘deep under the sacrum’ as a development from the queer sensuality of the poems placed earlier in the collection. Indeed the quotation ‘deep under the sacrum’ is from one of the most exploratory poems dealing with the poet’s individual body, Callery Pear, to which I will return.

The sacrum, an anatomical domain of the human skeleton is pictured below for the anatomically challenged, amongst whom I include myself. The sacrum was identified as identified and named in Classical Greece and the assumptions it concerned carried over into Roman religion and health-cognition.

Even a cursory look at an encyclopaedia definition of the word’s history shows that the anatomical area contained by the sacred bone (actually the pear-like shield formed by the fusing of the 5 anatomically vertebrae and the remnants of a tailbone, the coccyx) was largely filled by ‘reproductive’ and sexual organs. And it is to sexual rather than specifically ‘reproductive’ function of the surface and interior individual queer body that this poem refers to as will see in its closer reading below. In this poem and this phrase (‘deep under the sacrum’), we cannot know if Hewitt intended the mythological associations of our knowledge of this bony area to link to the sacred and, possibly to Greek and Roman sacrificial ritual, where some think sacral organs were so called because they were the votive parts of the sacrificed animal. Thus, although I would not claim that any sacred associations play a large part in this poem seen and read on its own, it does mark a point wherein the sacred will in the continuity of the poems serial development is invoked. Because this seat of orgasm claims depth (‘deep under the sacrum’) and it is into sacred and ritual depths that the rest of the poems will lead us, just as celebrants at Eleusis were led to a final theophany or vision of the appearance of God or the Catholic Mass leads us to find in the bread we make and eat the ‘real presence’ of God and God’s son in the fleshly body.

The poems as a whole have a kind of teleological purpose revealed finally in title poem at its end. This is for humans to see in experiential time:

what flesh can hold, the moment (l. 112)

in which a magnitude

can be carried inside a form

without it breaking.

Now this theological moment is in part the aim of the collection and the significant weight of the volume of poems. It investigates the flesh of the body as a container and inhibitor, both forms of ‘holding’ in real time. It looks for what is more than a body ‘inside a form’ of the body in the moment before that body fragments and bursts in death or ecstasy. I think the seventeenth-century idea employed by John Donne of death as orgasm ‘deep under the sacrum’ is implied here too. This vision – fulfilled through its connection to the carriage of a votive offering to God, the ‘host’ as in the Eucharist – is deeply informed by sacrificial ritual – the meaning of votive offering. In Adoration, this is experienced when his lover presents a blackberry to his mouth, prefiguring a kiss and a further taking into the mouth, as the poet kneels in adoration of the lover and the spaces they inhabit of each other including the interiors of the body, his head ‘is tilted up to God’, yet, like the material blackberry ingested, ‘I am a wild thing’:

distilled then taken gloriously (l. 58)

inside – host of the world –

The lines quoted earlier from the final and title poem are an elaboration of a line I see as key to the volume: ‘Our life is a theophany – ‘ (l. 111). Theophany is a term derived from the Greek (ἡ) θεοφάνεια to designate the manifestation of a God. It is a term utilised in understandings of Greek religious rituals or cults, and via Neo-Platonic readings of the pagan religious mysteries is used by Eusebius in 4th century AD Christianity to indicate the Incarnation of the Logos – the Word made Flesh.

But the key term in that phrase is ‘OUR life’. It is not only in an individual life and body then as at the end of Adoration but a life made up of multiple bodies in communion – the social body. In both the initiate mysteries (of Eleusis for instance as described by Plato) and Christianity that social body in toto shares in communion with God’s body and becomes its visible sign.

In Christianity, this is ritualised in the shared feast of Communion or Eucharist in which the body of Christ is made, shared and eaten by the social body. I agree with Zoffino that the key to this moment in the lovely poem of mutual queer love incarnate in Adoration, a poem Hewitt dedicates to ‘Nick’.[5] That poem is, as Zoffino remarked, the kernel of the religious and ritual vision of Tongues of Fire. I want to spell that point out much more to show that this is not by merely using ritual as a symbol or allegory but by impelling into queer bodies, whether singly or in congregations of two upwards the stuff of a human religion.

At the end of this piece I will assert that Hewitt does not make an easy end of this spiritual quest. In real terms the poet confronting the death of his father throws up more questions about his queer project than answers and I think the volume’s spiritual quest, like that of any Holy Grail, founders on questions of implacable mortality and the import to human life and art of reproduction.

However, on the strength of reading these poems, I’d argue that this religion is one cognisant of all the factors, including relations of unequal power, of the queer social body, as of all human bodies, whether of church, state, or communal organisation. A shared theophany – the revelation in ‘our life’, lies in communities of celebrants, or in one lone celebrant, bearing its votive offering of self to the appearance of deity it itself becomes through sexual love. This deity, I’ll argue (though oft named God in the poems), is nearer to a kind of Feuerbachian natural supernaturalism experienced in the communities of bodies.[6] I have no source as evidence traceable to Hewitt’s intentions to assert this of course.

In Adoration, the transcendent moment I’ve already quoted in which the poet ingests the ‘host’ of his partner’s body, is set on a heath where the poets are secret by the isolation of a ‘waste space’. but I think we are allowed to misread the poem if we think it in fact has a narrative that ends in isolation, because the event on the heath is a memory in time, which may or may not be prospective from the clinching moment experienced in a gay club where the lovers have found;

…a hidden place, turned

ourselves outwards in the humid cell –

bloom and spirit unspooling.

This is a moment of metamorphosis, focused on the word ‘turned’, which takes the inner and outer realms of the body and confuses their boundaries, as love does with the body and the embodied cognitions, even ‘waste spaces’, it contains and makes available to supernatural reading.

And that ‘hidden place’ that is a portal to the experience of each other’s bodies is in a gay club that is described as a cathedral of the body where liminal experience can happen: ‘vaulted columns’, ‘organ-warm, pulsing’, ‘ censer of white menthol swung’, and

… the music, a congregation

undoing their bodies, over

and over into beaming shapes.

This latter is quite a precise capture of the vision of bodies apparently fragmenting as they themselves move in the movement of strobe lighting but it also presages the shape-shifting liminality, on the threshold of the spiritual within a sacred space which presages the vision of the blackberry. It is a moment of sacred sex between two people in the context of a whole social body of other worshippers where things within and things within any setting lose their boundaries in the sacred confusion in which god make their appearance, a theophany.

I’m asserting then that Adoration is an early theophany in which ‘our lives’, queer lives lived in queer places, slant our nature into the literally adorable, the supernatural to which we tilt our head. Such moments though exist too in the Lantern poems. particularly the beautiful Dryad which explores a wood in which men meet for ‘casual’ sex, ‘acts of secret worship’, which becomes a portal, with its own threshold goddess marking a liminal boundary, of taking in the votive host, although not given a Christian context here:

….. an act

of kneeling to the earth, a way of bidding

the water to move, of taking in the mouth

the inner part of the world and coaxing it out.

However, though Dryad may prefigure the queer social communion of the later poems in which the queer world is allowed to slant nature and perception from its norms, it is far too secret, individual and alienated to constitute more than a repressed moment in which the men in the wood fail to see each other. I’d say that the volume as a whole needs to encounter private space in which queer men develop themselves before entering the social acceptance of each other, something that only finally happens though well prepared for in those half-elegies to his Father, and the Father. These poems are too difficult to successfully confront but I’ll come back to them, using the Tree of Jesse later.

To get to that point of experience Hewitt shows himself growing in acceptance of his own queer body before he confronts a queer sociality. To do so he learns strange lessons, like the meaning of orality as social ritual between male bodies, in the wonderful Old Croghan Man or in lesser more individual theophanies in the queer body in disturbingly beautiful and literally visceral poem The Callery Pear. These lesser theophanies I am going to describe, with no support in Hewitt’s own words, as epiphanies

The Callery Pear is one of the easiest of the poems to begin with for looking for what is meant by the queer body in epiphany or, to use a word from one of Hewitt’s acknowledged influences its ‘inscape’. Hewitt discusses his poetic mission in a revealing pieces, written on the day of his first major publication, in The Irish Times, of course.[7] He speaks there of two themes within the book: a community with recent queer writing, including of course Andrew McMillan, and ‘a passion for the natural world seen slant’, attributed to, amongst others, Gerard Manley Hopkins. ‘These two’ themes, as I have already shown here to are, in his words:

… never distinct. The body is the receptor, the focus of all of the poems here because they are, quite necessarily, all focused through my body. And so, in Tongues of Fire, the natural world is also a queer world, a bodily world.

Hewitt, S (2020b) ‘I would give all my poems to have my father back’ in The Irish Times, Thursday April 23rd. Available at: https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/books/seán-hewitt-i-would-give-all-my-poems-to-have-my-father-back-1.4218852

This gets nearer I think than the earlier quotation to how body, self, specific life-circumstances, and the observation of the natural world interact in the poems as a whole. However, for Hewitt, Hopkins’ theory of inscape, seeing things in their essential or epiphanic selves was already consciously a product of Hopkins’ self-acknowledged ‘queerness’. Hewitt quotes Hopkins in a 2018 piece:

“No doubt my poetry errs on the side of oddness… Now it is the virtue of design, pattern, or inscape to be distinctive and it is the vice of distinctiveness to become queer. This vice I cannot have escaped.”

cited Hewitt (2018) ‘A century on, the poetry of Gerard Manley Hopkins is still ahead of the times: Tortured visions of a poet priest’. in The New Statesman 08 August 2018. Available in: https://www.newstatesman.com/culture/books/2018/08/century-poetry-gerard-manley-hopkins-still-ahead-times

Now without a doubt, Hopkins uses the term ‘queer’ without any theory to interpret it and it is not therefore Hewitt’s intention to say that. However, Hewitt makes it clear that Hopkin’s notion of inscape is not only linked to Joyce’s notion of ‘epiphany’ by their common origin in Aquinas’ idea of haeccitas, or thisness but also to the sense of inner ‘vice’ with which he characterised his own sexual queerness.

We can see the conflation of the epiphany achieved in nature and queerness in Callery Pear. The poem refers to and captures, in an embodied perspective ’on slant, a tree (Pyris Calleriana) found in a cultivated form known as the ‘Bradford’ in the USA but also uncultivated in South East Asia. The poem however clearly locates these trees in an urban not rural environment. In tweets written in May 2020 Hewitt says that he had located those trees in Manhattan in earlier drafts of the poem. He also shared his own photographs of the trees there, taken in April 2018, which prompt the visual and olfactory experience of the poem:

the same smell, loosing now

in drifts, through the hot sheets

Hewitt choses ‘smell’, rather than ‘scent’ to signify the trees blossom as it fills the air and wind. This touches his body in the process of being taken in through nose and mouth. Hewitt stands out amongst postmodern queer poets for his insistence on apparent distance from ‘the political imperative’ by inhabiting a lyric tradition, best exemplified in Yeats: ‘its patterning, its rhyme, its insistent “I”’.[8]

It is then in unexpected slanted versions of nature that the ‘insistent “I”’ finds both its ‘breath’ in this air of a lyric air, patterning itself in movements internal and external to itself. We have seen how ‘the same smell’ indicates not only the repetitive sense in which the smell endures but how it spans the time-space from its capture in the daylit streets in ‘sheets’ and ‘billows’ to instance where the smell of self (sweat and stain) also is that of ‘another man’, where the object of desire is projected from the interior to the exterior congress of queer bodies in a congress across time and space of ‘sameness’/homo-sensuous-ness (if I may coin a portmanteau word):

sweated; the stain of myself

(smelling almost of another man)

held like blossom to my nose.

That last line bends back, in the way fluid lyric patterns do, to ‘the same smell’ in the second stanza, such that experience of nature is ‘slanted’ and queered. It is not only made strange to any normative expectations of the natural scent of blossom but to expectations of the love lyric. When I first read this I felt it was a poem about masturbation but if it is, it is only this as well as potentially about love shared within the agencies of more than one body, the agency which ‘held’ the blossom to my nose.

Because this is a poem where self may be acting on its own body is also whilst evoking the ghost of another who acts upon it (as the poem Ghost, preceding this one, shows more obviously. This may be because in writing from and about one’s own body attends not to bodies as wholes but as parts. The ‘fist’ clenching down ‘deep under my sacrum’ (already discussed above) may be his own or another’s, acting frontally or anally on his body, or a metaphor for how the action of smell feels in the sympathetic nervous system and the internal organs, such as the prostrate, surrounding that particular area of anatomy and involved in sexual stimulation and the production of semen and the sensation of orgasm.

At their fullest, Hewitt’s poems mark the rhythm of sex, as described by Freud as an effect of the greatest art too (in The Interpretation of Dreams speaking of Greek tragedy) as a cycle of nervous stimulation and inhibition – holding back before final all-consuming release.

and then, as I breathe, clenching

deep under my sacrum: a fist

of longing, call of silvered

nights when I would make

my body burst its bloom

then ….

That piece blends violent images and/ or sensations, such as the clench of the fist, acting also as a synecdoche of clenched buttocks (‘deep under the sacrum’) and the motion of the blood conveyed in insistent fast-paced rhythm and alliterative plosive ‘b’ sounds. If the body has a bloom it also, like the ‘Callery Pear’ emits a smell that is also loosened, ‘wafting / in sheets’ in the same place we ‘snug down, half -/ sweated’. That smell is also true both to the chemistry of both body odours (sweat from different hotly contained parts of the body and of semen and that which it stains. Hence these trees that represent nature to us here slanted to the bodies of conjoined men (I use the specific gender marker here purposively).

Semen has always been posited in the sexual emissions of the Callery Pear Tree, as have the rhythmic pulses of movement on and inhibition so important to the effect of lyric lines in poetry. ‘Stops me’ is a performative in the first line – it part helped by a Dickinson-like dash:

All of a sudden it stops me –

acrid and sour-white, wafting

in sheets as the pollen catches the sun

The poet whose lyric starts by just as suddenly stopping captures a moment of stasis where nature is almost surprised at itself, in the fullness of its air and ‘breath’ with stuff, its sense too of containment as an effect of nature trapped in what contains rather than releases it. And then there is a multi-sense observation of the blossom that is visual colour, taste, smell, and something slanted or off: ‘acrid and sour-white’. That sour is brilliant. It’s the moment the poem admits to the taste of semen as a function of the olfactory senses. As for smell, it’s ‘wafting’, ‘loosing now’, as if sometimes realised only in illusions of an object resolving into wind and light. As I’ve suggested those ‘sheets’ in line 3 live on through the short lyric to illuminate the bed conveyed in a synecdoche of action in one in stanza 4, wherein poet’s (and perhaps another’s or not) body will ‘snug down’.

The time-frame of this poem (early morning where pollen catches the slanting sun and the night) is part of the queerness of this poem, what Hewitt himself names in talking of the night-time feel of the volume as a whole as ‘an inversion of the world I grew up knowing’.[9] Poets who work with other queer poets do not use words like ‘inversion’ lightly, since they were the popular appellations of homosexuality in the first flowering of sexology. And here I think we need to look again at how and why Hewitt treats so sympathetically Hopkins sense that his queer way of performing things in the world, whether that be celebrant at a religious ritual, or as a writer or as a sexual being were a vice. Queer men, Hewitt knows are brought up in a world that not only looks aslant at them but also with shame. As Hewitt so beautifully says the bodily world of young gay men is one inhabited by internalised sense of being ‘in-the-wrong’ too: ‘growing into sex and shame that queer people experience’.[10]

The language expresses this in the contested nature of its attempt to express sensuous, sensual and queer experience, whether in the morning at the foot of blooming pear trees or at night in a mix of sexual action and fantasy whose participants may be one or more as half disgust and half engaged stimulation, half fearful violence and half celebration of life at the senses. Hence the ambiguity of ‘clenching’ and ‘fist’, separated so that they are not normalised as a known thing, longing and violent fragmentation in that alliterative ‘burst’. The idea of a sexual self, and/or emission that might be a ‘stain’ like Hopkin’s ‘vice’.

A reader who had not noticed that might retreat in horror: either, because the queer sexual element seems ‘unnecessary’ or because, they have so far progressed in self-knowledge that sexual activity is no longer a matter of dualities of good and what is feared to be evil (as I think it might be in Ghost) but only of celebration. The answer is that this is a poem of growing up into queer sexual being not of its attainment. We can see, if we expand our cultural grasp, in the Callery Pear tree, and cognitions of it, an objective correlative of such ambiguous developmental moments. Look for instance at the piece from corporate US literature in which the standing of the tree is discussed in the note marked here, which identifies here the chemical composition of its smell.[11]

That the flower and its emissions are so associated not only with the sexual but of body-odour considered as repellent rather than as sexual attractants tells us a whole story of the ‘civilisation’ of the sexual ‘instinct’, such that instinct is no longer the right name, a fact Freud often shared. The tree is thought an ‘invasive non-aboriginal pest’ in America not only for this but because its fruits taste horrible, a ‘useless ‘fruit’ indeed in the Anthropocene. There is already a problem for the queer body in making poetry here but it a problem pertaining centrally to queer lives which can form into both or either negative and positive cognitions and social cognitions and affects in the minds, bodies, and societies of people

Before I move on to a brief look in more detail through Ta Prohm at that attainment, we need to remember that sacredness leans forward and backward in the rest of the volume. It like The Tree of Jesse also recalls all the other tree poems in which the spiritual is found, including Callery Pear. But these latter poems also pass through a deeper sense of mortality and appreciation of the role of fathers and fatherhood lost. The wreck of Antonio della Porte’s bust of Arcellino Salvago in the Bode-Museum has before our poem raised the problem of how the queer poet faces the ‘fierce work’ of his conception by a father in the light of the mortality of the sensuous body.

a man, his mouth unlipped

by fire, marble of the face

peeled off in the blaze. …

One aspect of queer male experience this touches on is the sense of lost reproductivity, sometimes captured in the ‘waste’ lands of some of the poems, where the body is lost in time rather than reproduced. Even the fact the Callery Pear’s flower and emissions are so associated not only with the sexual but of body-odour considered as repellent rather than as sexual attractants tells us a whole story of the ‘civilisation’ of the sexual ‘instinct’, such that instinct is no longer the right name, a fact Freud often shared. The tree is thought an ‘invasive non-aboriginal pest’ in America not only for this but because its fruits taste horrible, a ‘useless ‘fruit’ indeed in the Anthropocene. There is already a problem for the queer body in making poetry here but it a problem pertaining centrally to queer lives which can form into both or either negative and positive cognitions and social cognitions and affects in the minds, bodies, and societies of people. It is this sense that the fertility of nature, even when seen slant must be confronted. The sense of what makes a man is shot through with the images of its role in fatherhood, especially in the cultural and spiritual mythology of the tree of Jesse.

The poem is based, as Hewitt tells us, on a Baroque exemplum of a common icon in Porto. This and other of the half-elegies must be approached with caution since their beauty is tied up in images of private loss. They follow however the same theme of the celebration of liturgical forms which confront and make God visible.

This morning, I sang to you

as I carried the cup of tablets

through the sunlit house

like a celebrant. ….

But, though extremely beautiful uses of the same liturgical imagery, I don’t think the half-elegies attempt to resolve the issue of queer mortality that I also see in Ghost in its raising of the problematic of ‘elective’ rather than generic blood-ties. In that poem it is hard to get beyond the ‘cold toom of my life’. . There is this question in Tree of Jesse too, wherein the father’s achieved growth, in the poet himself, is also reflected in the son’s guilt:

… your body

reconstituted, broken down

into growth, and I cannot unsee it –

the corpse of my father, some message

of guilt at my own living.

How are we reconcile the achievement n these poems of a celebration of the queer body at a both individual and social level, and there the recurrent fall of the poems into constituting queer life as a betrayal of the necessity of growth by reproduction, of genetic fatherhood. I don’t think we can, and I see it myself as a problem. The poem indeed that faces this is Ta Prohm.

Based on the poet’s visit to the famous temples in Cambodia, it unites thinking about his father’s dying in ‘the hospice bed’ with a religious act that attempts to resuscitate ‘something old/ and impossible’ to ‘save us’. There in the temple, Hewitt’s tree-worship poems that opened up a new almost pagan celebration of supernature, become almost a means of holding together something the age of which ought to have meant it had fallen into decay. Whilst a true description of the relation of tree to old temple (see picture below), it seems like something strong that merely holds fragile ‘human work’ together for a while.

There is no doubt the poems of Sean’s father’s death have thrown contradiction into the achievement of a celebratory queer poetry. It may be that they have started the process of the transformation of that vision and its mode of celebration into a new mode, which I also see in the lovely Suibhne (Sweeney) poems. These surround a beautiful, homoerotic poem telling of the love of Fer Caille for Suibhne. It is though, as such love often is in literature, only a marginal moment amongst a legend that is end-stopped and somewhat stuck in the pain of the elegiac. But then that conflict comes to all of us and is rarely resolved in full. Moreover, poems do not need to come to a conclusion as other projects do. Queer poets also recognise that their mortality is bound in the reproductive genetic lines of which they are part. Such problems cannot be wished away, only queered with their contradictions remaining.

Steve

[1] From the poem Tongues of Fire p. 69 in Hewitt, S. (2020: 65-69)

[2] I’m building here on an comparison of both publications published earlier in Zaffino, J. (2020) ‘Seán Hewitt’s Tongues of Fire’ Available at: https://severinelit.com/2020/04/28/sean-hewitts-tongues-of-fire/

[3] ibid.

[4] Hewitt, S. (2019) Lantern Offord Road Books, pp. 21 & 27, respectively.

[5] Tongues of Fire, ‘Acknowledgements’, op.cit.: 72

[6] Summarised by Todd Gooch as the iconic symbol of ‘an atheistic humanism that renounces the fantastical consolations of religion in order to embrace the historical tasks of human self-realization and the creation of the political and cultural institutions that are conducive to it’. Gooch, Todd, “Ludwig Andreas Feuerbach”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2020 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2020/entries/ludwig-feuerbach/>.

[7] I say ‘of course’ because it the poems demand the understanding arising from a Catholic cultural history, if not Catholicism itself.

[8] Hewitt (2020b).

[9] Hewitt (2020b)

[10] ibid.

[11] We come in contact with the smell of amines every day in the form of body odors, like under the arm pits.

The fishy odor produced by the Bradford Pear is likely a combination of two amines called trimethylamine and dimethylamine, according to Richard Banick, a botanical manager at Bell Flavors and Fragrances. Although perfumers know what chemicals produce the fishy smell (trimethylamine is often used an indicator of how fresh a fish is) they can’t be certain what causes the odor of the Bradford Pear, said Banick.

…..

Rodgriquez suspects that the volatile compounds in the Bradford tree are there as attractants, and not necessarily to repel pollinators.

Later, the trees produce little green-yellow fruits that you cannot eat.

Business Insider ‘Why all of New York City smells like sex these days’ Available at: https://www.businessinsider.com/bradford-pear-tree-semen-sex-smell-2013-4?r=US&IR=T

2 thoughts on “‘Our life is a theophany.’ Reflecting on Seán Hewitt’s (2020) ‘Tongues of Fire’.”