‘Try the occupation of your imagination.[1] … “End the Pre-Occupation”’. Reflecting on Colum McCann’s (2020) Apeirogon London, Bloomsbury Publishing.

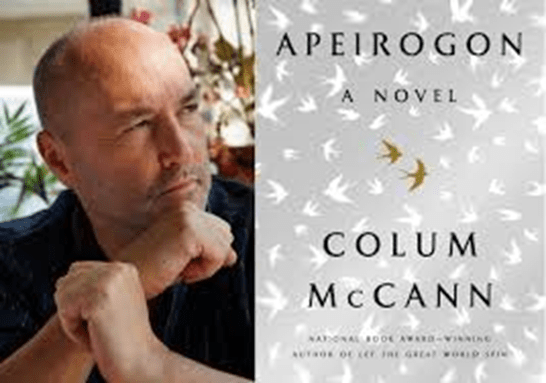

Certain words have power. Near the end of the novel whilst the Palestinian peace-campaigner, Bassam, a character based on interviews with the ‘real person’ of that name and role (shown above), speaks at a conference he also reflects on his speech as he speaks:

It was Occupation that got them. Just the word. He wasn’t quite sure why it rankled so much, but it did – it was always the word that seemed to slide a little dagger into the ribcage.

McCann (2020: ch.24, p.445)

This is very much a novel about how people under conditions that are unproductive of speech, demonstrate both the need to speak and maintain that speech in the face of resistance, whilst describing the effect of the forces which resist and restrict their speech. Military Occupation is one such force and we see it in simpler terms doing just that at an earlier point in the novel. Stopped at one of the numerous ‘flying’ military checkpoints that the Israeli military make appear in the Occupied territory during Ramadan, when it is known that Muslims might be more ‘irritable, tired, hungry, ready for a cigarette’, Bassam:

…knew not to say much when he rolled down the window. No confrontation, no rancour, but he didn’t want to be obsequious either. He nodded, waited for them to speak. Most of them used English. A few of them had Arabic. He seldom showed recognition of any Hebrew, nothing fluent anyway: it could be a sign he had been in prison. He spoke to them slowly and with precision.

ibid: ch. 190, p. 85 my italics

We might almost not notice here that how one speaks, even the language chosen where one has such a choice, but also the timing, pace, tone and pragmatics of the speech are heavily pre-determined by the context of situation that we describe as ‘occupation’. But the whole novel centres, quite literally as we shall see, on the way in which the two characters get to make complex speeches that will provoke resistances across diverse and often mutually unsympathetic audiences. Because the two central characters speak of things that people prefer not to hear. They are resisted by those audiences who, whatever they say, will hear it as the words of enemy terrorists or collaborators or both and hence not hear the complexity of what they speak at all.

The resistance to speak plain is at the core of the Jewish peace campaigner Rami’s central speech (we’ll return to why I call it and the one by Bassam central later) and it starts by community’s self-policing the very words they speak. Rami says:

Some people have an interest in keeping silence. … Fear makes money, and it makes laws, and it takes land, and it builds settlements, and fear likes everyone to keep silent. And, let’s face it, in Israel we’re very good at fear, it occupies us. … We use the word security to silence others. …

ibid: ch. 500, p.224

Some words themselves ‘rankle’ because they describe a situation which some will fail to recognise and dispute. To see Palestine, or even part of it, as ‘Occupied’ is one such situation. To hear it is to trigger fear and ontological insecurity, as Bassam senses in his speech in New York near to the end of the book and quoted above. Rami makes the point clearly shortly after the one in the quotation directly above:

It may sound strange but in Israel we don’t really know what the Occupation actually is. … We have no access to what it’s like for people in the West Bank or Gaza. Nobody talks about it .. We drive on our Israeli-only roads. We bypass Arab villages. …

ibid: p.225

This silence is not only the ‘silence’ which we equate with the absence of sound, it is the rooting out of any experience (visual, olfactory, tactile) that contradicts or appears ‘some sort of weird distortion of reality’ and is hence judged ‘impossible’.[2] The novel then is about ‘speaking’ and even ‘showing and not just telling’ (as novels can do) realities that we prefer to ignore because we prejudge them as distortions, lies or unreal. Not only Palestine is occupied, as Rami says of the psychological state into which Zionism has historically transformed, but not it stresses necessarily forever, where fear ‘occupies us’.[3] Hence my title. To end Occupation is to end ‘Preoccupation’ (a point made tacitly and otherwise throughout the novel). Psychological preoccupation edits the space into which data enters into consciousness to be evaluated not just the kind of data allowed to enter.

It is not just that military occupation has socio-psychological consequences that get internalised. Thought to offer ‘security’ for some, preoccupation imprisons all into a space already occupied (preoccupied by fear and low self-estimation). Told of the primal danger of ‘The Occupation’, a ‘sort of haze drifted over his listeners … They had heard so much, they said, and yet knew so little.’

He demurred. For him everything still came back to the Occupation. … It was destroying both sides. He didn’t hate Jews, … What he hated was being occupied, the humiliation of it, the strangulation, the daily degradation, the abasement.

ibid: ch. 277, p. 123

This experience of being heard and yet not heard, because the focus seems too reduced to one essential for both ‘sides’ is crucial to the novel. Even here where the word ‘sides’ seems to function to create a binary – indicating that there are only two sides to an experience – we are fixed momentarily in a thought that imprisons. For Bassam, sides proliferate, not least in his study of the Holocaust – through which he enters into the experience that created Zionism. In doing so he realises that, as T.S. Eliot says, ‘humankind / Cannot bear very much reality’.[4] Whilst studying ‘Peace Studies’ at Bradford University, he walks around the streets reading books and taking notes that he later finds it difficult to ‘decipher’:

… Memory. Trauma. The rhyme of history and oppression. … What it might mean to understand the history of another.

It struck him early on that people were afraid of the enemy because they were terrified that their lives might get diluted, that they might lose themselves in the tangle of knowing each other.

…. He liked the notion, now, of being thrown off balance.

ibid: Ch. 279, pp. 124f.

The ‘psychologising’ of the concept of ‘occupation’ and ‘preoccupation’, such that it means the preoccupation of being known in a form that does not change, and that therefore feels safe and ‘secure’, allows us to see how individual identities feed off myths (themselves based on memories and trauma) of national or racial identities and how each constrain each other to preserve a sense of delusional ‘balance’. There is a trivial instance of the selectivity of national myths in the way in which McCann uses Bradford in Yorkshire as an exemplum of an English university city. Englishmen ‘rolled their eyes’ at the mention of this city so that Bassam ‘could almost see their disdain’ because it was not London, Manchester or Cambridge.[5]

It is more seriously exampled by those of his own community who refused to understand why Bassam chooses to study the Holocaust rather than the history of the Palestinians displaced after 1948. Only by seeing all of the sides of any question can you stop falling into a binary conflict between two sides. That is because it is not ‘balance’ that people preserve, although the term comforts them, it is merely fearful self-limitation, and often morbid preoccupation with stereotypical self-concept.

This maintains an apparently ‘safe’, whilst paradoxically embattled, self-concept that sometimes needs to occupy the other and keep the source of resistance to its ‘reality’ at a distance, whether that be Bradford or a recognition of the real horrors of the Holocaust. Holocaust reading brings in new information about the Zionist project, from many sides that not only unbalances any feeling against Israel and Jews but also the simplified Palestinian self-concept that antagonism is used to maintain. It is only when Bassam loses balance that he begins to see the world as an emergent complex whole. But perceptions of such wholes remain hard to speak of or to show.

To be clear, the novel does not seek to achieve a ‘balanced’ position on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, it rather serves to illustrate how and why psychologies of normative balance are powerful and to show that if ‘reality’ is complex and emergent, it is also probably inarticulable, except in dreams. My own suspicion is that McCann explores solutions, if that is what they are, in the exchange of letters between Einstein and Sigmund Freud, the story of which he tells amongst many other stories that shoot off at tangents from the whole story.[6] From that reading, reading actually performed by Bassam, come the phrases from Freud’s letter to Einstein that make the entirety of chapter 278:

A community of feeling. A mythology of the instincts.

ibid: p. 124

I don’t want here to explore the weight which McCann gives to these phrases in the novel other than merely to signpost that they offer some partial, and of course, unsatisfactory picture of the domain in which violence starts and might stop. I’m aware that I leave this theme unarticulated but that is, in part because the novel never allows for fully articulated solutions or even descriptions of the problem.

But what it does do is explore cultural symbols that might speak to the heart of the problem of why problems never get articulated or spoken, although an attempt to articulate them must be made from the perspective of all subjectivities immersed in these problems. Most complex of these cultural symbols considered is that with the forms, media and characters of writing, but into this area I won’t even tread.

Instead I’ll briefly deal with a domain characterised by symbols that lie at the heart of our normative understanding of objectivity, normativity and certainty – mathematics in the Islamic tradition, particular with regard to geometry and number. Algebra too, we are told in the novel, was based in medieval Islam on a concept of spiritual balance focused on the fulcrum of equivalence and this could be explored in terms of how the novel interrogates balance. However, I concentrate only on the concentration on numbers and sacred geometry. The title of the novel is, after all, the name of a geometric form that it is impossible to form visual or mental cognition. The entirety of Chapter 181 is:

Apeirogon: a shape with a countably infinite number of sides.

ibid: p.83

The following chapter goes on to show the way in which we understand the idea of the ‘countably infinite’ but it does not because it cannot offer a sense of what shape we should cognitively hold or draw for visual perception. But this is one of the key problems of the novel – to imagine the ‘sides’ in any problem that might add up to a shaped whole, a solution to the problems facing its characters. The novel jokes with the limited ability of human cognition to hold even lesser numbers than the ‘countably infinite’.

For instance, consider the picture of the very real Senator George Mitchell being unable to imagine the very many forms in which Palestine is politically represented in so many representative ‘sides’ that he found it ‘difficult to find a straight edge with which to begin.’ The following chapter calls this ironically: ‘A countably infinite number of sides’.[7] This playful use of geometry is there to show us a domain in which apparently objective measures lead the mind inevitably into qualitative issues, sometimes immune to numeration, including the concept of infinity.

This is riffed upon when patterns in the ‘sacred geometry’ from Islamic tradition are evoked such as the minibar, an Islamic pulpit, made from patterned shapes that interlock such that, ‘the resulting geometric effects … were almost unfathomably intricate’.[8] And beyond algebra and geometry is that fact that, in Ch. 135 in its entirety:

Among scholars of Islam, mathematical numbers are considered to be not just quantities, but qualities too.

ibid: p. 392

Even in dealing with this theme of the novel though I intend to merely point to an area for detailed study by others not me. The point of arriving at the significance of numbers at this point of my piece is to justify my earlier point that novel centres on the articulation of complex human stories in resistant contexts. The concern with numbers in medieval Islam is thought to have led to the ninth-century revision of the ‘ Thousand Arabian Nights’ to its form as ‘1001 Nights’ in the ninth century too. Apeirogon numbers its 1001 chapter such that chapter 1001 appears as the central chapter, roughly half-way through the novel. It is about a central theme or quality of the novel too: how we look and listen to the work of Rami, a graphic artist, and Bassam, an oral storyteller, respectively. It is about the reader ‘reading’ the novel in time:

… we sit for hours, … our memories imploding, our synapses skipping, in the gathering dark, remembering, while listening, all of those stories that are yet to be told.

ibid: ch. 1001, p. 229

That reading attitude, so long in cultivation for most readers, that listens in the present, remembering its past experience and anticipating the future is the central experience of the novel and hence in a sense not only the middle but the starting and ending chapter in terms of its handling of the qualitative experience involved when we listen to stories. This point is underlined in the fact that the numbering of the chapters to either side of 1001 follow an ascending and descending linear sequence respectively, 1-500 and then 500 – 1. This means there are two of any chapter other than chapter 1001. The doubling of these numbers will lead to interesting comparisons that I don’t know the novel well enough to try out now. But of clear importance is that the first chapter 500 is a long telling of Rami’s story, including the death of his daughter, Smadar. The second chapter 500 is the equivalent life-story, focused on the death of his son, of Bassam.

It is obvious that these stories mark the qualitative concern of the novel with trauma and memory. Elements of the stories and these themes also appear in piecemeal, from many ‘sides’ (here meaning perspectives or ‘points of view’) in much of the rest of the novel. But the rest of the novel also overwhelms by showing that these two stories have no real limits in history, geography, subject or person – travelling through space-time as if in a complex pattern more like a story-web than a story-line.

Thus the story of the Dead Seas Scrolls is relevant, as is the discovery quite separately by an Irishman, Costigan, of the Dead Sea itself, and as is the story of the lies of the English translator of the Arabian Nights, Burton. Einstein and Freud have already been mentioned but did we really expect a small part of Pascal’s story in the second chapter 76.

As a reflection on a novel this piece finishes now with some dissatisfaction on it’s writer’s part. There is inevitably too much in this novel because its patterns play with the inarticulable in all articulated stories, including those absences so central to most stories. As a book about boundaries, it will test those in all of us. It is a magnificent novel

Steve.

[1] McCann (2020: ch. 277, p. 123)

[2] ibid:225

[3] ibid: 224

[4] ‘…human kind / Cannot bear very much reality. / Time past and time future / What might have been and what has been / Point to one end, which is always present.’ Eliot Burnt Norton (sec. I) from The Four Quartets. Available at: http://www.coldbacon.com/poems/fq.html

[5] ibid: ch. 275, p. 120

[6] The part of the Freud / Einstein story dealing with Freud’s delayed reply to Einstein’s query about the problem of violence between human groups is found ibid: Ch. 254, p.111.

[7] ibid: Chs. 416f., p. 180

[8] ibid: ch. 134, p. 393.

11 thoughts on “‘Try the occupation of your imagination. … “End the Pre-Occupation”’. Reflecting on Colum McCann’s (2020) ‘Apeirogon’: Booker 2020 Selection 1”