The Meaning of Exhibitions in major national collections: Reflecting on the absence of Sin in London between 15th April to 5th July. Stimulus for reflection Joost Joustra’s (2020) Sin: The Art of Transgression London, National Gallery Company Ltd.

Mark Brown’s preview of this exhibition in December for The Guardian uses the title, ‘National Gallery Hopes to Tempt Crowds with Sin exhibition’. The play on the cognate status of temptation with those of sin is to be expected. I’ll return to the role of narratives in the construction of ideas for exhibitions later. What Brown could not have expected was the devastating effect of the coronavirus pandemic on the ability of institutions to exhibit art to its customers. Suddenly there was no-one to tempt!

The National Gallery nevertheless have published the book of the Exhibition this month and I read it today (the 18th April). Of course had I seen the 14 ‘exhibited works’ listed ‘in the flesh’, as art historians say, then their own qualities may have washed from my mind how the exhibition ‘frames’ them, so to speak, in narrative.[1] But left with book and pre-emptive review, reproductions of whole paintings or details from the paintings in the book cannot be divorced from the narratives chosen to arrange their sequence and juxtapositions. Those formal matters in published art texts take precedence, where even the placing of reproduction vis-à-vis text is part of the storytelling.

And we start with a title and subtitle. As always there is a play in subtitles on how concepts that motivate the narrative to be told are made into ‘art’, our apparent interest in going to see the exhibition of paintings. But ‘The Art of Transgression’ may create more expectations than the exhibition, and certainly the book’s narrative, will sustain. At Tufts University in the USA students of an art course are supplied online with readings that show why the ‘transgressive’ is important in modern art, including a 2017 piece from Fintan O’Toole which contains the following:

the transgression of ( ) boundaries gave the avant-garde much of its energy, from Dada to punk, from surrealism to the photographs of Robert Mapplethorpe or Tracey Emin’s installation of her unmade bed and stained sheets. Transgression raised the stakes. It gave an edge of danger and courage even to work that was otherwise mediocre. It made audiences and readers feel that they were involved with the artists in an act of rebellion against bourgeois piety and institutional repression.

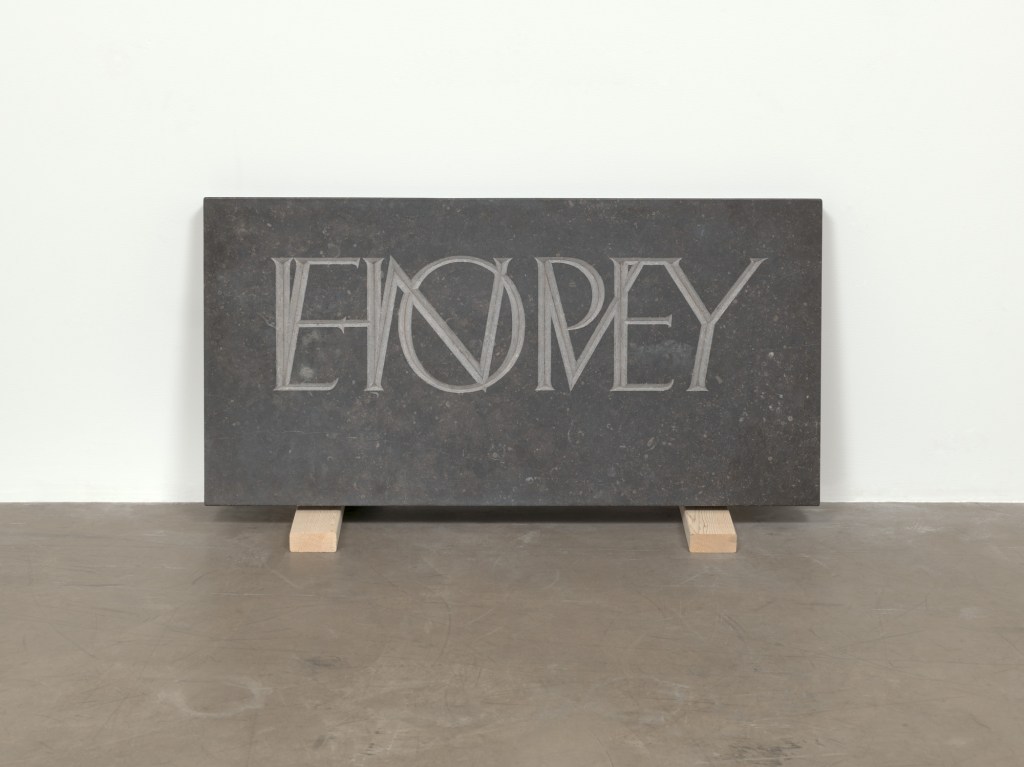

Transgression involves crossing boundaries. Yet, despite the fact that many visitors of this exhibition would have been aware of the word to talk about a tradition in art, even in Renaissance art, ‘transgression’ in the narrative of this show appears to be merely a synonym of ‘sin’. At most it might stretch in the section of the book with the same title as the main subtitle to apply to what Joustra calls, in relation to Bruce Nauman’s Hope/Envy (1941) in which the words carved in a palimpsest, ‘fluid boundaries between each sin and virtue’.[2] But you’ll look in vain for further elaboration of the idea of the boundaries that sin crosses or the boundaries between sin and other concepts

And it is the lack of such elaboration that characterises the book and perhaps would have characterised the exhibition. In Brown’s review, Joustra is interviewed and speaks of why Velázquez’s The Immaculate Conception (1618-19) was included:

“It is a very beautiful picture to look at and if you walk by it you don’t necessarily associate it with sin,” said Joustra. “But it is very much about sin.”

Mark Brown (2019) in: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2019/dec/10/national-gallery-hopes-to-tempt-crowds-with-sin-exhibition

I feel very let down by that statement, ‘it is very much about sin’. In the catalogue Joustra examines the painting, alongside the same painter’s contemporary Saint John the Evangelist on the Island of Patmos (1618-19). The text does discuss the details of the painting but merely to pick out how the imagery of Revelations was super-charged with meaning in Baroque Counter-Reformation Spain, as the virgin birth of Mary became emphasised as matching the virgin birth of Christ. To those who accepted that doctrine, including the Carmelite patrons who commissioned the painting, both were to be conceived as immaculate, as bodies, female and male respectively that emerged in the world without the mediation of other sinful bodies in naked congress.

Joustra goes on to hypothesise from her appearance that Velásquez’s ‘looks like she just stepped off Seville’s streets’.[3] Yet never at any point is the potentially ‘transgressive’ act of using a real woman considered as itself possibly a ‘sin’. For, even if a virgin herself, she was ‘born in inevitable sin by the copulation of her parents. And that is the only way in which the painting could be said to be about ‘sin’ rather than the apotheosis of what is not and cannot be sin in either its generation or function.

Now this isn’t because no critics have helped us to find ways to see this problem up close. The Romanian art critic Stoichita in 1995 discussed both of the same two Velásquez paintings discussed by Joustra today and concluded they formed a diptych. His emphasis on saying this was to stress that the Immaculate Virgin could never be conceived as if she were a representation of a model who looked like any woman from the Seville streets. The aim is to see an image unmediated by the flesh of a non-immaculate woman. Something that could only be seen in a revealed or sacred vision rather than something related to any earthly (and therefore sinful) prototype. The vision is captured in words that stress the visual in the rhetorical for of a hypotyposis.

The only flesh we should see in the virgin is the ‘word made flesh’. For Stoichita the diptych emphasises that the description that John forms as a result of his vision is then the only source of what we are asked to see is something we would never otherwise be able to see except by direct divine revelation:

… what we see in the panel of the Immaculate Virgin is description become painting. The written text is transformed into the pictorial image, …

Stoichita, V. (1995) Visionary Experience in the Golden Age of Spanish Art London, Reaktion Books Ltd. p. 116

Stoichita is a subtle thinker. His main point is that representation of the sacred is problematic. If in this case if we are to see sacred purity, the source of that act of vision becomes implicated and cannot but be damaged by assumptions of an profane model from a world of sin – a sacred artist, that is, may use any profane material, including a model, to realise their end. Thus Joustra’s assumption of a model who could appear on any Seville Street is already an issue – already, that is introduces sin into the representation of the sinless. What I want to emphasise here is that in as far as Velázquez, partakes in an art of transgression, he is making us aware that art is itself potentially a transgression, it is a work of human hands, a version of the Byzantine idea of acheiropoieta, a work not made by human hands but pure vision of spiritual reality.

Of course, I’m assuming here, with Stoichita, that the artist’s work is not directly accessible to common sense. Yet if we unpack Joustra, it is. She seems to be saying something like this: the painting contains the imagery from Revelations painted around the representation of a real-life woman who modelled for Velásquez. In contrast, I would say that the set of assumptions there will not get us anywhere near to what it was to be a Counter-Reformation painter of the spiritual in Baroque Spain. More importantly, it will not tell us how and why The Immaculate Conception is ‘very much about sin’.

Is then this exhibition really about either ‘sin’ or ‘the art of transgression’. In the last example this could only be so if the exhibition made available to us how the concept of sin came to be associated with the acts of the life and work of painters. Nothing in this catalogue goes anywhere near such ideas. What then was this exhibition about? In this I think Mark Brown is near to the truth: sin tempts crowds, and crowds are the aggregated quantities that art-institutions use, besides money, to evaluate artistic success. Thence sin is our subject because it is a popular theme, especially if we already have the main holdings in this subject. Half of the 14 exhibits are already owned by National Gallery, and 2 are from the London accessible sister collection of the Courtauld Institute. One need then only source 5 from less accessible collections (2 are from the artists themselves).

To summarise the ‘charge’, if charge it be: during lean years, national institutions increasingly focus on finding ways of exhibiting the work they already own and/or which is accessible. And our role becomes to show success and thus to go for themes which bring together popular subjects. When it comes to articulating the theme the need for popular easily accessible explanations are part of the same force. This is how Joustra’s book strikes me: as rather lazy intellectually and seeking a popular style which, although it may inform, never challenges the reader to think.

This isn’t because I am saying that they are judging the intellect of their audience but rather testing its staying power by reducing issues that contain some abstraction if they are to be fully understood. As a result, I doubt if they are aiming at making art at all available by provoking challenge and that means challenging norms of how we see and think about what we are seeing. Hence any ‘ambiguity’ discussed is at a very basic level, such as in pointing out the similarity between images of Eve and Venus.

The notion of ‘deniability’ Joustra introduces relates to the fact that though pictures of naked bodies and sexual practice may tempt a viewer to sinful thoughts, the intention to do this can be denied by claiming these pictures have a moral meaning through the use of symbols and allegory.[4] In more modern times, feminist meanings often overtake the religious themes allegory leads us to. But this in no way makes art more accessible or allows access to its rich meanings to more people. Instead it forms a diverse narrative to justify pre-selected great paintings:

- Explore the ambiguity and blurred boundaries in early images of sin;

- Look at images of sin and sinful behaviour;

- How sin is done away with and redemption is found.[5]

This narrative never really gets to grips with painterly themes – the relationship between the theme and the painter’s role in painting it, although it may dabble in notions related to the intentions of art patrons. Stoichita, on the other hand, really shows us what it might have meant for a painter to paint in sin.

Thus I don’t feel I am helped to understand further Lucas Cranach’s beautiful Adam and Eve (1526) in its patterning and distribution of colours and shapes, nor how these link to meanings in ways that explain why the visual medium is different from the use of literary (including the sacred literature) uses of symbols like serpents.[6] I want to know why the central figures form patterns of shapes, especially triangles and what it meant to paint Eve’s serpentine tresses in the way they organise light and dark differently and compromise nature by obvious ‘art’, craft and artifice.

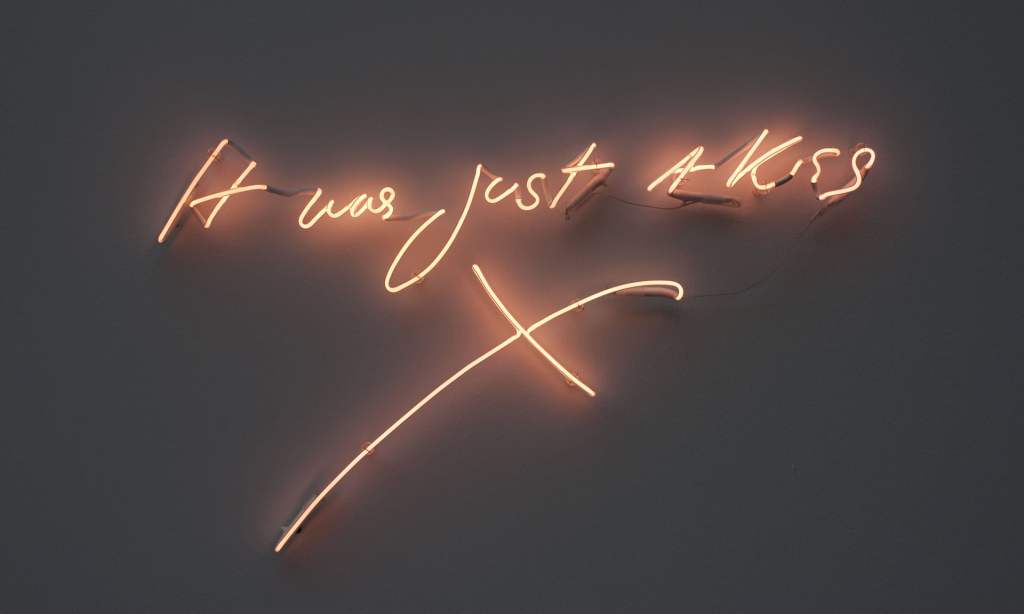

And though the inclusion of Tracey Emin’s It was just a kiss (1963) is justified in the book, we aren’t told why this kind of conceptual art equates to sin its form – neon lighting patterns being significant in themselves – but rather about the literary meanings of kisses. The whole rationale of conceptual art could have been evoked.

I particularly wanted more in the analysis of Hogarth’s The Tête-à- Tête (c. 1743) since this is the picture in the exhibition from the set Marriage-A-la-Mode. It is briefly examined but only to point out social meanings we might miss – like the signs of the pox as represented in paint. I want more than guesses in statements like: ‘The wife’s satisfied expression hints at her part in more adultery’. [7] To which we might say. Perhaps. But it doesn’t explain the fact that she represents the only life drawn out in paint. She is the attractive centre of the painting.

As I reflect on what I’ve said here, I’m aware that the faults I see in the readings is really about the fault in the institutional narrative used to justify it. It is a narrative focused on the fate of notions of sin that derive mainly from Christian and Christianised classicism. It carries nothing from other cultures – even those of Classical Greece and Rome though they are indicated. The absence of reflection on art from other cultures ensures the story of what ‘sin’ means comparatively across cultures and focuses more on a dominant narrative in a dominant culture, even more so when sin crosses from sacred to secular contexts.

I feel I need more from our institutions that educates about the basics of why, when, and how art is made, and the variability and diversity within that wider set of narratives, rather than tell stories blazoned across dominant cultures. The problem of institutions is that they stagnate – living on the capital of their treasures just by varying the order in which they are displayed and the narratives used to connect them together into some kind of presentable unit.

But that we have missed something great in perhaps not being able to see these great pictures ‘in the flesh’ (though I hate that lying term) is not in doubt.

Steve

[1] List in Joustra (2020: 102).

[2] ibid: 42

[3] ibid: 74

[4] ibid: 27ff.

[5] These three steps summarise the narrative of book and exhibition in ibid: 12.

[6] ibid: 18

[7] ibid: 46, 52