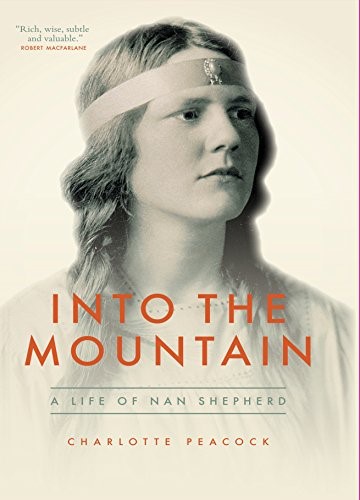

‘… excited, with no cause that the wit can define’.[1] Charlotte Peacock’s (2017) Into The Mountain: A Life of Nan Shepherd Cambridge, Galileo Publishers.

We never write a life: we, or least Charlotte Peacock, writes the meaning of the patch of time between life and death. This large project starts with smaller acts in which meaning is sensed. The quotation – from Nan Shepherd’s The Living Mountain – in the title is part of a description of the scents released by plants, in this case birch trees, in the prolonged and interactive processes of their gestation, living, dying and decay. It comes in a chapter evoking the networks that knot life forms together and aid each other to live and die in root and rhizome formations: a process that Robert MacFarlane extends in his book, Underland to the understanding in particular of the importance of fungi.

Both writers, the latter finding himself strangely interlocked with the former from the moment of discovering her prose and poetry, puzzle over the fact that life and death are networked in invisible and recessive spaces (underlands for MacFarlane). But Nan Shepherd posits too other networks without which we fail to recognise the being of an external world, those interior to the body. Networks which bring together the senses: sight, smell, touch, hearing and inner proprioceptive organisations of those senses, wherein not only the eyes but the feet ‘see’, in order to be able to know a landscape. Nan’s sentence cited in the title is about the connected networks of the nervous system wherein bottom-up perception at the senses interact with the top-down operations of intellection, not always to the latter’s benefit:

Acting, through the sensory nerves, it confuses the higher centres; one is excited, with no cause that the wit can define.

Shepherd (1977: 40)

If the brain is a network, it is not necessarily hierarchically coherent. It tangles and knots together in ways that frustrate the higher centres who claim to be in control. In the body networks fuse together in inarticulate but co-sensing knots (con-fusion).

The interaction of life and death then occurs between two networks but that is only a partial way of seeing things. Those two networks are themselves really parts of a larger network, too large and complex to succumb to binaries like mind and world and/or mind and body. Note the mind is still part of this interaction: but only in its struggle to make itself know the world and body it thinks to be, quite wrongly, separate and of a different substance from itself.

I wanted to show why those complications are necessary (well I think so anyway) to explain the significance of a renaissance of interest in Shepherd. That renaissance as exemplified by Peacock is both faithful to its subject as is traditional but also innovative as literary critical biography. It may be that Peacock does not seek innovation exactly – rather just an absolute absorption in the narrative of life and death here. Biography, after all is motivated not by turning a life into an object but in a practical act of questioning what constitutes the ‘end’ or purpose of any life.

I take the idea of ‘ends’ seriously. A life can be recreated with a view to examining the purpose or aim of that life – and that forbids us from equating anyone’s death as an end of a life short and simple. The life is a something which serves many ends. It is in contemplating such ideas that Peacock ‘ends’ her book still open to multiple interpretations of the purpose of that life one has experienced in reading. How Nan’s death might be appropriately remembered, and on what journeys to what new ends, is how this story of a life so brilliantly and complexly ends (Peacock let it be remembered is herself a poet).

In her penultimate paragraph Peacock extrapolates a sentence from Neil Gunn’s last letter to Nan in order to moot the idea of scattering Nan’s ashes on the Cairngorms. Is this image itself a beautiful and satisfying end that expresses the purpose of the life of an author? After all she wrote poetry collected as Into the Cairngorms, a phrase silently cited in the following extracts:

according to Kathleen Jamie the practice is altering the chemical balance of the soil, ‘fertilising it … to the detriment of rare Alpine plants’. … Like Mairi in Gunn’s Butcher’s Broom she would no doubt have preferred to walk into the mountain again, leaving no sign. Instead, she lies buried … in the family lair at Springbank Cemetery …

…. It seems somehow too orderly, too neat and domestic a resting place for Nan Shepherd. But it is peaceful; a good place to be. And there are more ends than the grave.

ibid: 258f. My italics in emphasis. The quotation From Jamie, K. (2008) review of Robert MacFarlane.

For some this is plain enough prose but we shouldn’t fail to see how it itself plays with ends that become beginnings, with multiple possibilities therein arising. Nan’s ashes might have contributed to changing the ecology of the mountains such that the life of Alpine plants she saw as part of the entire being of the mountain were ended. How are we, let alone she, to think of such possible ends among a multitude of others. Ends that include the life of written characters such as Mairi, whose end, as written by Peacock, is in the phrase beginning Nan’s poetry of the mountain.

It is of course possible to go too fair in finding complexity in a prose where meanings are meant to be circumscribed but although the description of Nan’s resting place in a lair, matches exactly its use as term in Scotland but not England as a ‘plot in a graveyard’ in which family members are buried together, the English meaning of a place associated to ideas of the wild, animal and human disorderly seem to haunt it for me as a reader. Thus that last sentence places Nan in an end-stopped resting place that bears the reason why it is for Nan too ‘orderly, neat’ and domestic. For those who like settled readings I’d go further to argue that the verb ‘to be’ is an important sentence ending for someone who ends her book, The Living Mountain with a chapter entitled ‘Being’.

Likewise the fact that the multiplicity of ends that end the biography include ones involving more than merely decomposition in the grave. Those other kinds of end seem more concerned with a teleology of being – being going beyond simple versions of ends in linear time. And therein lies the complex philosophies of time which Peacock shows us to have been discussed by Nan with both Neil Gunn and others. Thus writing to Barbara Balmer in 1981, Nan says important things about the writer bring words written well before they will be read becoming present and alive in time not past and dead:

Time. I always knew that time didn’t matter but took old age to show me that time is a mode of experiencing. …

… they carry (the writer’s) whole theme on to a level where a reader can share the experience. It’s as though you are standing experiencing and suddenly the work is there, bursting out of its own ripeness … the life has exploded, sticky and rich and smelling so good. …

Nan’s underlining. NS to BB 15 Jan. 1981 Cited ibid: 258.

In these extracts life is evoked in a way that transcends the temporal and spatial distances between writer writing and reader reading such that life is experienced in being as something strangely over-sensuous and over-sensual in the mediating words themselves, as a relationship so present that it could be experienced as too close and potentially violent. It explodes and is stickily hard to remove from the skin and other sense-organs. It certainly isn’t neat, or orderly or domestic. It certainly challenges and bursts through the barriers that make up conventional norms of early twentieth century bourgeois Scottish life.

Nan Shepherd could be shocked when women became ‘coarse’ in their writing, as Jessie Kesson recalls when describing Nan’s response to her Glitter of Mica. Kesson realised that this had more to do with class than any hint of being a ‘prig’. The working-class women Kesson represented in her wonderful novels just wouldn’t, in the presence of a ‘Lady and educated’, speak as Kesson shows them to do where that inhibitory presence is physically absent. Nan, Kesson implies, would not, as Kesson does, use words relating to female sexuality that were ‘down to earth and uninhibited’, since educated ladies did not do.[2] But educated ladies knew about and could refer to sexuality in the distancing and disguising metaphors of sticky fruit, especially women who knew Christina Rossetti’s Goblin Market.

What excited Nan Shepherd in other writers such as Neil Gunn, Peacock shows us, is the liminal life between boundaries and particularly the boundaries that sustains normative binary concepts such as life and death, right and wrong and stone and water. She adopted this as almost a feature of the Scottish Renaissance in which with Gunn and MacDiarmid she was central. She was saying so as early as her novel The Weatherhouse in 1930: ‘… limits had shifted, boundaries been dissolved. Nothing ended in itself, but flowed over into something else’.[3]

Beginnings and ends are also binaries that flow into each other, just as nothing ends in this last queer sentence but rather flows over and into other unnamed things and whatever looks like something bounded ‘in itself’ is not contained but moved into yet another interior. The loose way in which the experience of moving or going into something is central and this is true of the multiple ways and ends that are represented by the ‘life’ of Nan Shepherd. And if for Nan Shepherd ‘sharing in a profound experience’ meant that she ‘was inside’, it also meant that what mattered was being ‘in itself’ rather ‘for itself’ (the latter where being is lived as if an external end or task, a teleology). Or as it is said in her story Descent from the Cross of 1943:

no philosophy to offer the world, no book to write, nothing to say. … No more agonising struggle for words; words that had refused him because there was no task to perform.

cited ibid: 215

Hence no doubt the difficulty of a poet like Peacock, one submerged into her subject, to note how such a life ends, tracing itself in the land and in the words of others re-experiencing that land, like Robert MacFarlane and Charlotte Peacock. MacFarlane is quoted by Peacock in Nan’s life. He:

is largely responsible for the recent resurgence of interest in Nan Shepherd. … “I first read (her) in 2003 and was changed. I had thought I knew the Cairngorms well, but Shepherd showed me my complacency. …”. …

ibid: 251

Resurgence of being for Nan comes from her writing entering into the reading of another person and in her reproduction as a living force in that person. I can’t prove it but this is the feeling I get about Peacock’s life which is transmuting Nan Shepherd into a living force that is the written biography read by an excited reader.

I deeply admire it and feel I am admiring not a life or a person but a life-force bursting into being and being experienced by myself in a life-changing manner. For me that comes through, for example, Peacock’s explications of how Nan gives us new access to other concepts we thought we already understood such as ‘landscape’.[4] This is richer than just adding to our reading of her an understanding of Eastern philosophy taken in part from Neil Gunn and his fiction, including one of my favourites Wild Geese Overhead of 1939.

I need to read Shepherd more but armed with Peacock those readings will be more meaningful. I have, for instance, since being taught by Karl Miller at least, been interested in the use of the doppelganger or double in Scottish literature. It was in a disturbing experience of the fear of her own doubleness, Peacock tells us, that she began to doubt Cartesian dualism and that, even experientially, to feel that the ‘relationship between body and mind was not as she had supposed’[5].

She would have found this theme in Gunn in particular but perhaps both owe it to James Hogg, that giant standing between the English and their understanding of the depth psychology of Scottish literature. She experienced herself after a thyroid operation contemporary to those reflections as a person, trying ‘to live with my new self’. That new self was the material body in which alone she would find significant human meaning rather than in God, spirit or even ‘mind’.

I can’t recommend this life enough.

Steve

[1] Shepherd, N. (1977 1st published, p.40) The Living Mountain in Shephed, N. (ed. Watson, R.) [1996] The Grampian Quartet Edinburgh, Canongate.

[2] Kesson cited ibid: 237

[3] Cited ibid: 153

[4] The ideas are developed c. ibid: 209f.

[5] ibid: 220

One thought on “‘… excited, with no cause that the wit can define’.[1] Charlotte Peacock’s (2017) ‘Into The Mountain: A Life of Nan Shepherd’”