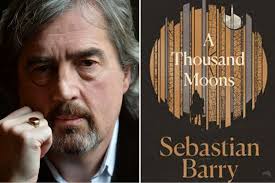

Articulating ‘queer speaking silence’[1]: Queer reflections on desire and sex/gender in Sebastian Barry’s (2020) A Thousand Moons London, Faber & Faber.

OR “Longing for something I had no lingo for, …”.[2]

One of the most disappointing of the features of the reviews of this book was their use the fact that this book is a sequel to evaluate it. Silently or out loud this fact is made to mean that the sequel is bound to be inferior to what it follows. In the case of Sebastian Barry, this is compounded by the long acknowledged fact that all of Barry’s books, and often his plays and poetry, form a web of connections loosely based on the history of the McNulty’s and Dunne’s that form his family’s past; whose rhizome like associational properties are usually called Balzacian – and perhaps more accurately could be called Zolaesque.

No book of his then stands alone and newspaper critics, as they seem to find their function, like to rank them in terms of literary value by spoken or unspoken criteria. I want to bring all that backroom talk into the open so I can disavow any wish to enter into it or even to doubt my faith that a writer like Barry only writes again when he feels he is adding to a discovery in his past fiction. Because, for me. A Thousand Moons runs with themes that both go with, and beyond, Days Without End (2016)

If the latter novel, his seventh, came as a great surprise to fans of Barry, it was because it was so radically a male gay novel from a writer not expected to produce one. In the Edinburgh Literary festival following publication, Barry described it as a work in honour of his gay son. It handled gay themes by explorations not of what it means to be gay but by establishing within it a challenge to the norms by which we read a book. The build up of the sexual relationship is a surprise because it contains no long psychological examination of the precursors to sex between the men nor did it make assumptions about nature that couldn’t accommodate queer turnabouts in events, about which society and law has something to say, often wrong-headedly, but assumptions about nature never.

The ‘nature’ of which Barry writes is thoroughly queered. That brought him the usual criticisms from the Daily Mail that things could not be like that in nineteenth century America: views that he rebutted with researched evidence. What I’m trying to say is Barry does not honour his son by inventing gay characters to announce support. He explores what might be queer in history and why those things are continually crushed by heteronormativity, and its more dangerous cousin homonormativity.

He deals too with cross-dressing in both novels brilliantly, as a complex expression of disturbances in the sex/gender grid of sexual differentiation that are continually suppressed by belief in the biological truth (more august than God in its believers eyes, and unsullied by any other kind of truth) of SEX.[3]

Now he does maintain the main characters and develops the story on chronologically in ways that reflect a robust support for chosen family relationships, based on of their hidden ubiquity in history. But I think he writes this new novel because he has further extended his understanding of the queering of rigid norms. A Thousand Moons is innovative just as much as its forerunner and based on cognitive developments and further exploration of queer embodiment and affect that the author has added to his craft toolbox. The book deliberately explores at its centre female sexuality, not for the first time but in very different way from say Annie Dunne or A Secret Scripture, both novels I nevertheless love.

This novel attest to a sound knowledge of sex/gender relationships and remains nevertheless alive to the need to examine and understand male sexual violence and rape (especially the vulnerability of women to that terrible crime) often in ways that demand, unbeknownst to the gender-critical, queer theory to explain them. One instance is in the exploration of the crucial roles of the recurrently appearing but minor crucial character, Frank Parkman. We shall see but not until the very end that his sexual life is as important to the narratives of war and sexual violence as more obvious main characters, even those from Days Without End. It isn’t fair to say why because that would be a major spoiler for readers who read for story, development of theme, or both.

Queer theory, of course, is not about concentrating on lesbian and gay characters, as if a group apart, but on an insistence that desire is not normative nor easily read from the surface actions of any performed act of love and/or sex. The role of violence in all this is important too, not only in the ubiquity of phallic symbols like guns and knives, even perhaps the clitoral symbol of the ‘little knife’ so much and so significantly associated to Winona, the main character who is a developing girl/woman. Barry marks the novelty of approach in this novel by careful attention to one of its major symbols, moons, significant mostly in the plural than the singular.

Of course the symbol of moons is a time-honoured one and Barry, I think, calls on many of its possible referents, as a symbol of non-Christian femininity and fertility (Winona uses the term ‘moon’ to name the first experience of the menstrual cycle in a native American camp), possible too the meaning of moons may have Marian touches). These symbols also connect to the idea of the moon as a complex periodisation of time in which cycles of life, death and regeneration are implied within the otherwise linear progression of time, in which the moon’s phases take on especial meaning. A ‘thousand moons’ is itself a measure of duration that indicates qualitative duration, whilst invoking some symbolic quantification, wherein a thousand represents an instance of a very large number.

In all cases the moon is touched with a potential religious and ritual meaning that can be seen as either a means of good or evil, light or dark, clear-thinking and insanity, beneficence or ill-meaning. Such binaries play with perceptions of meaning that vary sometimes with the gender of the perceiver – with patriarchal value-systems emphasising the sinister, associating the moon more with the dark night in which she appears in her power rather than the light with which she contains the dark by her own powerful illumination.

Events that occur in the night are hence often charged in this book with power but also ambiguity, in which associations with femininity, madness, sexual promise or vengeance abound uncertain of their meanings to all and every character in the book. Much of this play occurs around the figure of Jas Jonski and his mad mother (recalling The Sacred Scripture here), a very ambiguously mixed figure of the victims and perpetration of patriarchal violence

For Barry, the symbol is used in conjunction with his concern with the articulation of time and memory: time past, present, continuing, projected, introjected and recalled. Hence the concern in the novel with its rhythmic periodic symbolism in natural cycles lived by all animals and made into conscious symbols by human animals. The moon illuminates but it illuminates what is in obscurity it also falls upon, often mixing with darkness to make nothing much more than that obscurity.

For Barry, this becomes a metaphor for the process of remembered narrative itself from the start of the novel. Winona, the first-born daughter, is the originator of the narrative but that narrative can seem even to its originator as little more than the ‘mire of remembrance’, which we cross by as trusty a path as the many and all untrustworthy we can.[4] The whole passage shows her suspicious how how time is quantified in numbers but which also casts doubt on these numbers accuracy:

It could be I am taking about things that occurred in Henry County, Tennessee in 1873 or 4, but I have never been so faithful on dates.

Barry (2020: 18)

There are other problems in this sentence, of course, not least the reliability of our narrator. The confusion on dates, after all just numbers of years in a periodisation of history, runs counter with the skill with ‘numbers’ we know, as the novel progresses, Winona appears to master in her role in the employ of lawyer Briscoe. The educated Winona, together with the white rebel named after a master of classical culture, Aurelius Littlefair, knows, and boasts in, the power of education and equates it with quantitative skills, that explicate even the fate of armies in the American Civil War.

“…. McClellan’s trouble was, Mr Bill, he could not count. I hope you have your numbers?”

“I do,” I said. I was going to say I worked for the lawyer Briscoe but thankfully stopped myself.”

“I regret that Peg is a child of the wilderness. … …, I will be sending all the children to school. For education is the same thing as salvation. …”

ibid: 176 (note Mr Bill is Winona ‘disguised’ as a boy – of which more when we consider cross-dressing later)

Winona, in disguise is a Winona capable of deceit for a cause. Deceit (conscious or unconscious) produces unreliable narration by, if not lies, omission and selective memory. Is that happening for Winona from the very beginning when she slips playfully, and sometimes in earnest to save her life, between performing identities available to her of gender, race, cultural mode of thinking? You learn, after all, at lawyer Briscoe’s the importance on relying on precise numerations of dates and times.

When Winona says she has ‘never been faithful on dates’, the term faithful is used archaically but is also ambiguous – it performs a necessary ambiguity in its reliance on the uncertainty of human cognition, especially memory, which can extend to deceit, as any theory of mind psychologist will tell you. Terms therefore like, ‘It could be …’, in the quotation above or ‘If I say…’ below can indicate either uncertainty of cognitive function or performative pretence.

If I say that here following are the real events, you will remember that they are described at a great distance if time of their happening. And there is no one to agree or challenge my account, now. …

ibid: 18

The final sentence cited here is chilling coming from a lawyer aware of how important the survival of evidence, particularly human witnesses, is to determine the truth of a matter. Many people who contest the truth of an account die or are simply ‘shut up’ (in both senses of the term) in this novel, of course. In a lawyer’s office, after all, documents ‘were sometimes speaking things, sometimes silent as snow’.[5] Amongst those silent documents are quantitative accounts of slavery in ‘black souls’ and the clearance of native American tribal communities. Anyway, ‘ … numbers didn’t weep and were needed for everything’.[6]

It is common for heroes who challenge norms (whether racial, cultural, or based or based on the power implications of sex/gender) also to be represented as potentially economic of the truth whilst sometimes passing as the opposite (take Jane Eyre, for instance). Such ambiguities are anyway justified by the historical and social contradictions in which they must survive, if not fully live. I sense Winona as one such. And, as such she has developed from absorption in queer theory to which Days Without End was a mere introduction, in honour of one’s son. But Barry is an innovative thinking storyteller. He does not just repeat his past successes.

One could take unreliable narration further as a theme that is artistically metareflective but my interests lie elsewhere, and I no longer value what some call ‘academic focus’. But let’s take one instance of why ambiguity is not necessarily a surface phenomenon nor one from which obvious ironies can be unfurled in the moment of our reading. For instance, Jas Jonski rides to Winona to help him, we think but are not sure, cover up the fact that he raped Winona. In the midst of conjuring up her and our own uncertainties about Jonski’s innocence or guilt, Winona says:

He came clattering up the track on an old horse he must have begged off his friend Frank Parkman at the town livery. Of course I had not been near town ever since and I suppose he must have been waiting for me to reappear there. Who knows how his mind was working.

ibid: 33

This might be the most innocent piece of recitative narrative of any novel, merely stating that at this time. like the theory of mind I invoked earlier, Jonski’s mental state is unknown to others. It is only when we reach the very last chapter of the novel that we will realise that Winona’s suppositions here hide other less normative potentials in a blank irony – an irony that will be unseen by most and perhaps by all at first reading.[7]

Where Barry takes the concern with queer theory is to hasten the demolition of simple binary accounts of motivation that pass as reason, even binaries as deeply validated as truth/lies, man/woman, quantity and quality. We experience life sometimes as a cycle between binary extremes but often it is a more complex dance of interactions between extremes and across their range. Winona is the moon in that Briscoe trains her as to spy on the road on which ‘mysterious dark men’ pass at night certainly but more importantly for her at half-light. This is because it presents mysteries whichever end of a binary appears to be in control of the progression of time: the union or rebels, new or old, the known or the strange:

Twilight was an awful busy time sometimes on that road. This was even the though the new governor was all for the old rebels, and they had got their votes back too, whereas the previous one had been all for the Union, and taking the votes off them – or indeed because of that dance of time.

ibid: 21 (Barry’s emphasis)

When time is more complex than being either progressive or cyclic, it’s best described as a dance where binary antinomies cross each other’s boundaries, sometimes proximate and sometimes distant and sometimes indistinguishable. This dance is symbolised in Winona’s native American mother who reconciles the opposed, such as an otherwise invasive delegation from the Crow tribe, in moments of magic but also the roles of men and women, especially the fear one builds of the other through loss of power.[8]

Winona explains the magic her mother possesses by the assertion that she ‘was a story herself’.[9] And stories measure time, as do myth, ‘dances’ and symbolic art in ways that appear to transcend time because they loop and cycle as well as progress. Hence they confound numbers with qualities when accounting for time. This is explained by Winona through her mother’s imagination of great epochs of time – the ‘thousand moons’ – in which tragic outcomes in the past, the death of a tribe from plague, are called by their character’s return to life if we can travel thus far in the story of their resuscitation and presentness of the past in the future present.

A great sickness had come to us, said, a thousand moons ago. Almost everyone died. … Oh, how we feared that story, A thousand moons was her deepest measure of time. … For my mother time was a kind of a hoop or a circle, not a long string. If you walked far enough, she said, you could find the people still living who had lived in the long ago. “A thousand moons all at once”, she called it.

ibid: 31

There are varied ways in which a conscious play on the idea of the ‘measure of time’ occurs in the novel. The word associates with cyclical patterns in art such as we find in poetry, music and dance. It also refers to how abstractions of experience such as love as well as time are evaluated: as, that is, quality or quantity. They help interpret other symbols of narrative – such as the very common one of the river running from source to goal in the sea. Here the loops of a river transform the depth, speed and distance of flow but not, essentially its linear run to a known end. Considering whether she should have shot Sheriff Flynn before the main story got going, Winona reflects:

So that would have been an end to that and we would never had heard that strange talk. The river of things goes or sometimes takes a swirling turn. Of course, all turns, all shallows and rapids lead eventually to the sea. The story of life goes only to the same shore.

ibid: 59

Even the partial end to many Western stories -the establishment of a home or household – is drawn into the play of whether such a home is a matter of things counted, like money or resources, or of a system of values or qualities beyond numbers. For instance working as clerk of works in rebuilding Briscoes’ house destroyed by arson, she knows that a ‘house is a web of numbers, …. Numbers for this, numbers for that’.[10] But a house has a tendency to abstract those numbers into feelings and meaning.

It was numbers, that house-building. Numbers, like little songs, like little birds. A small heaven of numbers. … But then there was no past, present, and future, as my mother knew. There was only a loop turning in tightly on itself, over and over.

ibid: 158

The transformation of the quantitative into the qualitative is part of the magic of the narrative as it defies the accumulative norms and sequences of a straightforward history. We get an early taste of that in the way Thomas McNulty tells his story from its origins in Ireland to his present chosen home, family and fluid sex/gender in which he remained the same – a criterion of enduring value:

Thomas McNulty always said he came from nothing. He meant it to the letter of the phrase. All his people died far away in Ireland, just as mine did in Wyoming. … He said he came from nothing but he lived with kings and queens now. It never entered his head that we were nothing too.

ibid: 23

A literal move from nothing to nothing (0 to 0) becomes a qualitative transformation when queered from the norms of social judgement by imaginative and re-creative play with those norms. Psychologically for Winona it is the equivalent of having a self-esteem unwarranted by any quantity of evidence, based on the choice of a grouping, already-present as the Native Americans or invented as in the queer family of McNulty and Cole:

I think now of the great value we put on what we were and I wonder what does it mean when another people judge you to be worth so little you were only to be killed? …

Nothing, nothing, nothing, we were nothing. I think about that and think it is the very rooftop of sadness.

But maybe that was why Thomas McNulty and John Cole loved me, because I was the child of nothing.

ibid: 31f.

All of this is a matter of how we value, and hence how we ‘measure’ the meaning of lives in the stories we live, the deaths of what valued worlds we cause and the those we choose to create from absolutely nothing – not even ideas like genes or measures of social status such as a countable income. Speaking of the comparative evaluation of native American by those who live it and those who destroyed it, Winona says: ‘We set a great value on each living one of us. But the white people’s value set on us was not the same measure’.[11]

It is perhaps to make a leap to go from this concern with the transformative power of the stories we tell ourselves, even in our chosen groups, from being evaluated as nothing in the social gaze (as that for which the enforced term ‘queer’ was once the abusive term) to a self-evaluation that uses a different ‘measure’; the measure of art. Hence the ‘queer’ is and can be that mix of elements – of gender, orientation, race or class – that is chosen despite validating norms.

It is a leap we need to make however to establish the significance of this novel that I have only hitherto asserted in my title. What sustains stories we tell ourselves about ourselves as individuals and of the groups that make that individual life sustainable is esteem. To esteem one’s life and group depends on a certain ability to use the language of difference differently. In doing so we don’t ask that a word to set boundaries round an existent thing but help novel things to cross boundaries and interact with each other and existent things. And this is how queer theory built.

The simplest social language discussed in the novel is dress. Dress sustains cognitions, pragmatic function and imagination for Winona for instance. We have seen it used thus by the male gay couple in Days Without End and, though less so, we see it as a potential for their older selves in this novel. Transitional dressing help groups to end the static inflexibility imposed by norms. But the main vehicle of the language of dress are the exchanges of clothes and properties, including guns and knives, between Winona and Peg in A Thousand Moons. Their love and desire for each other is engineered from these transitions and the liminality in which they happen. Take the way clothes act here to create an apparition outside sex/gender in which new choices can be made and novel behaviours attempted, where body and mind, biology and social categories interactively play.

She was a sort of apparition, a sort of appearance of something. I could sense the heat in her skin under the rough cloth. I only had to reach out with just my mind to feel it. … The colours of things are not really blues and greens and reds, there are softnesses and shadows of colours that slip away from any word to say them. That was how she was coloured. The set of her green eyes, …. the lovely mouth, painted as if by some dainty god – was I not in my secret mind and thinking in my secret thoughts like a man? Well, fortunate then that I was in men’s clothes.

ibid: 167

It would be completely incorrect to see here a validation of the heteronormative, since the processs involved here are transitional and liminal in their sexuality. That there is a convenient and playful serendipity in the language of dress used is part of a greater transition which eventually will need neither the static identities of male, female or even of female and female to describe sexual ‘meltdown’ in the space between Peg and Winona.

We use dress as a language that appears at first to validate categories like male and female when we appear to have no alternative languages. If our desires are not symbolically encoded in a culture they are a ‘something’ that has, at least for a time, no straightforward language to describe them. Preciado says that this requires a queering of the norm into a language (“a strange lingo”) that has potential to represent the new.

“To speak is to invent the language of the crossing , to project one’s voice into an interstellar expedition: to translate our difference into the language of the norm; while we continue, in secret, to practise a strange lingo that the law does not understand.”

Preciado, P.B. Trans. Mandell, C. (2019) An Apartment on Uranus London, Fitzcarroldo Editions, Locus 245.

I discovered this passage after I discovered the concern with language and language mixes in Barry’s novel, but it helps to describe why queering and language work together to describe our differences from norms whilst evading the attempts of norms to capture those differences. This is precisely what is happening when the chosen family of Winona is visited by normative (or so it seems in the time) representatives of the law. As attitudes clash, the house is suspended in ‘a queer speaking silence’.[12]

There are lots of languages in the novel, as many as there are cultures and media to need them, including languages used in silence like Tennyson’s self-invented sign languages. Tongues are torn away too or that is threatened. Rosalee and Tennyson’s language, that of Africa, has been robbed from them and they are represented in the language of their owners of European origin.

Yet remnants remain and these convey queerly meanings they cannot cognitively understand: ‘Rosalee sang an old song in a lingo she herself didn’t know but had earnestly learned at her grandmother’s knee’.[13] Languages are cultivated that seem queer, as in Jonski’s letter but which are interpreted as weapons: ‘The religious lingo was a blade to slay me.’[14] Winona, even from the very start confronts desires she cannot name: ‘I sat in my manly clothes and longed for something I had no lingo for, English or Indian’.[15]

If language cannot describe our queer feelings, thoughts and senses of identity, neither can it describe that which drives us socially and psychologically and this may be true of Frank Parkman too.

It is a good place to end my piece in showing why this is a great novel, in which novel feelings and thoughts that load motivations remain unknown until our languages, stories and estimations of self-evaluation stand against norms imposed to make the world static for the interests of the very few.

Suddenly I wondered, how many people were in America? Thousands and thousands. And here we were, just two of them, and one not knowing why she had ridden in there, and the other not knowing even why she breathed in and out. But something in that riddle was wanting to loose itself.

ibid: 167

Thus, in that last sentence, is Barry’s brilliant version of queer theory. Here desire seeks to free itself from the chains of old and oppressive conventions which is all we may sometimes have to shape those desires otherwise. To free them, we’ll have to queer them.

Steve

[1] Barry (2020: 58)

[2] ibid: 97

[3] There is no point in delaying it. My beliefs are those of a long-term LGBTQ+ activist and are explicitly antagonistic to the gender-critical ‘case’ based on the biological certainty that they see in binary sex differentiation. My use of the term sex/gender is based on, but not argued here, the work of biologist Anne Fausto-Sterling, which she summarises in Fausto-Sterling (2019) ‘Gender/Sex. Sexual orientation, and Identity Are in the Body: How did they get there?’ in The Journal of Sex Research 56 (4-5), 529-555. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2019.1581883

[4] summarising Winona on her own narration, ibid: 18

[5] ibid: 20

[6] ibid: 21

[7] Spoiler in footnote (leave now if you hate spoilers): That is that Frank Parkman’s role in this sentence appears as merely a background cipher and will turn out o be massively significant – the irony suppressed is that no reader at this point will have guessed at the abusive sexual relationship between Parkman and Jonski. If that is so, that is because we are all locked in normative assumptions.

[8] this summarises and interprets material from ibid: 30f.

[9] ibid.

[10] ibid: 156

[11] ibid: 51

[12] ibid: 58

[13] ibid:155

[14] ibid: 193

[15] ibid: 97

7 thoughts on “Articulating ‘queer speaking silence’: Queer reflections on desire and sex/gender in Sebastian Barry’s (2020) ‘A Thousand Moons’”