Reading Danez Smith – ‘Don’t Call Us Dead: Poems’ (2018 UK, Chatto & Windus, London) & ‘Homie: poems’ (title for brothers, my nig , not to be said out loud by white people) [2020 USA, Minneapolis, Graywolf Press).

this book was titled homie because I don’t want non-black people to say my nig out loud

From ‘note on the title’ of homie/my nig in front matter Smith (2020: (v))

http://www.citypages.com/arts/meet-danez-smith-st-pauls-internationally-celebrated-black-queer-poet-and-selfie-icon/567174391

oh sweet God if you be my nigga

don’t never take my niggas from me

lest i be a black and yolkless language

…

.., lest i be whittled down

to not a nigga but a n-word

….

From my nig p. 67-70 Homie

Danez Smith says he does not write for white people, even though they may learn from his poems. In his note to Homie (above) he poses this as an issue even in relation to his titles. This note presupposes white people who come into contact with the poems. But there’s another distinction there: white people may ‘read’ either title. What they, in particular, must not do is to ‘say’ the term intended for his black readers ‘out loud’.

I do not have answers for the questions this note raises in me. After all what, for Smith, is the distinction between reading and ‘saying out loud’ the words that construct poetry?

Of course the particular phrase ‘my nig’ is defined by a contributor to the Urban Dictionary as a term meaning ‘my dawg, my friend’. As so often street use gets defined by street use synonyms. Look ‘dawg’ up and you find it synonymous with ‘homie’, both indicating a man’s very close male friend.[1] But ‘nig’ is a contraction of nigger. Some people engaging in the business of definition see it as deliberate shortening of ‘nigger’ to avoid the offensive racism of the term when used by white people to name black people.

These words live in the voice and in the voice interacting with others in distinct social situations in which the power between two people is mediated. A black man naming his black male friend ‘my nig’ implies a shared identity as well as affection. A white man doing the same can only be indicating social distance and otherness, a reduction of the other, even if said in loving intention, to that point of difference. That is sufficient to understand why ‘my nig’ must not be said aloud by white people, whilst the recognise as word, not intended for their use.

But then we should consider that ‘homie’ (shortened from ‘homeboy’) has similar issues), indicating a similarity of identity deriving from coming from the same town. And my nig is, complexly given all I’ve said, also the title of one single poem about love between queer black men in the collection.[2] It’s implied white people can say that title loud, and that it will not be offensive.

In fact I think we can’t come to such conclusions from playing around with propositions as I do above. The point is that Smith is demanding that we become aware that language performs acts of distancing that replicate power relations and that spoken poetry is no different. Look at Danez performing dear white america on Youtube (use link here) and compare it to your reading (if you are white) of that poem.[3]

That prose poem spends most of its time showing that ‘this’ (which I take to refer to the poem or more strictly its performance in sound and body) is the possession of an entirely black audience and orator – it is possessed as a relationship, outside those normative to what is called Earth by a white dominated society, that ‘is ours’.

i’ve left Earth, i am equal parts sick of your go back to Africa & i just don’t see race.

And that is because Earth has already been stolen and named by white language that likes to see itself as innocent of harm, and open to all audiences. Hidden in those audiences is the fact of differentiation of treatment of white America of its people based on racial difference that must remain unacknowledged if white america is to remain fundamentally white. White America only says ‘why does it always have to be about race?, in order the more successfully to make america the America of white dominion and white names and naming in language:

i’m giving the stars their right names, & this life, this new story & history you cannot steal or sell or cast overboard or hang or beat or drown or own or redline or shackle or silence or cheat or choke or cover up or jail or shoot or jail or shoot or shoot or ruin

There is no way to claim possession of the right to ‘a story or history’ than to tell it in your own words. And words that were used to own slaves must be words free of cultures that enslave while calling it it something else.

Now that is what we hear and see of the presented prose poem. It has some differences from the printed text in its content, but only ones that emphasise the more that ‘we’ (the person speaking and those spoken to, for whom the poem is said aloud) will claim what is ours and that means keeping our own language, refusing it to those people in whose mouths, said aloud, it would mean a different thing.

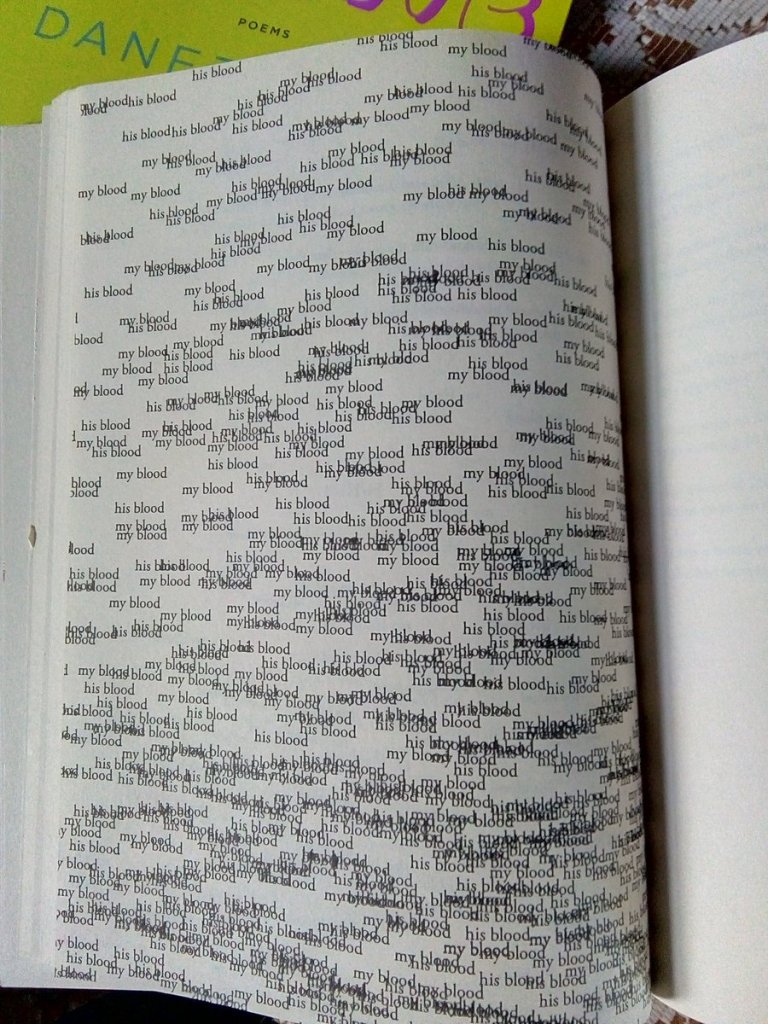

The effect of being owned by the language of others though in Smith’s poetry is also experienced by those who become the object of a language in which they themselves are marginalised, erased or written over such that nothing is left of their record but the blur caused by the palimpsest in which they, or we, are overwritten. Thus the wonderful poem litany with blood all over.[4] In this poem a man tested for HIV positive status is silenced by language, especially the blood tests that redefine him and silence him as a person:

test results say I talk too much

test results say i ask none of the right questions

They also obliterate the relationship between he who speaks in the poem and the ‘boy’, whose infected blood, is part of parcel of the speaker’s status, the status of his blood:

i let the blood

raise my boy

i let the blood

bury him too

Much of the poem uses a conceit in which T-cells are imagined as children, the colour charts of testing becoming ‘rivers of my drowned children’.

But this poem could not be performed, as dear white america superbly can, just as voiced artwork. It demands visual knowledge of the page and that we learn from the marks upon it, both black and white. I think that the reduction to visual black and white invites both black and white audiences equally, because what intersects them is a language – that of test results. And we neither say this poem aloud nor read them, as we conventionally understand reading.

On that page we are attempting to read that which is obliterated, say in a palimpsest methodology of inscription, or the blurring of words in visual patterns of black and white on the page. It’s a page that has changed its nature: no more normative patterns of unidirectional lines, margins and uniform densities of black and white differentiation that makes up print. These words could not be said out loud either, they are a signal of the page taken over by a medium alien to it, the flows and patterns of my ‘drowned children’.

Now I don’t consider the discursion into Smith’s work on HIV+ identities to clash with what I said about the primary importance of black audiences. Smith is a poet of intersectional identity, a queer poet in both senses but primarily one that acknowledges that identities are not bounded by one marker of identity.

I find that particularly poignant in the homie (2020) volume. The poems here use the same domains of topic: intersecting poems about articulating HIV+ status, black communal identity and its languages, and positive identities forged out of negative language by ownership, as in beautiful simple poems of language reclamation like niggas or on faggotness.[5] They also combine poems intended to be spoken and communally consumed and those that live alone on the page, as text or as text and shape (for the latter see rose).[6]

And rose is a complex poem which addresses as topic and as audience both black and white identities in intersection with gender, and explores not only the love in ‘my nig’ relationships but the possibility of collusive male violence against women. And that needs you to learn differently – not by performed common values but by queered patterns that must be read so that they are not simplified.

Rose, ‘a white girl & not pretty’, is broken by gang rape: her fate allows the implicated speaker to know ‘we were so mean. That he was ‘the bastard fuck in the mob of bastard fucks’. I would guess that Smith knows he is on uneasy ground here, precisely because he touches on subjects that are routine fictional stereotypes of black identity in white culture, of sexual and other violence, and gang culture. But he faces it because queer identity is a matter of norms continually disrupted and it is Rose’s ugliness that is punished as outside such norms. That she is white is less important but it shows that intersected identities can make anyone marginal and subject to the violence of norms in protecting themselves: we killed that girl.

I barely know where to go with this argument except to assert that homie is a very complex movement on from the earlier collection of poems. The movement on is I think a recognition of the fact that the violence which patrols and rules the norms of societies is experienced differently by different people because of the intersectionality of human identities and the more difficult sense that communalities in human experience exist also.

A black gay man is not the same as a white gay man but there are commonalities. The commonalties must not substitute for a return to colour-blindness in any other section. A person of HIV+ status may also be a woman, a man, gay, straight, white, or black but that fact of intersectionality must not obscure that an intersection of disadvantage and the historically marginalised. But this view gives some Smith poems a different tone, especially to dear white america.

I have no answers to the questionable frameworks in which I’m inserting Smith. And that is because I suspect that he’s a much greater poet than I yet have the power to read. Hence I’ll keep reading him. I’ll end by looking at an instance of that different tone, a poem called, white niggas.[7]

Something in me wants to evoke Frantz Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks in this poem as if it’s dialect was about the ‘self-oppression’ of black people forced to act white but I’m avoiding that, because if it’s there, I think it only as one layer of possible meaning.

It certainly is a story of a ‘marriage’ (a gay marriage I think) in which the partners are allegories of white and black. What goes behind the house is a physical fight between ‘your narrative & my narrative’, differing histories but ones in which the cards are fixed in the favour of the white partner. He still possesses ‘actual instruments / of my end: badge, bullet, post, gas, rope, opinion.’ These means of fixing a superior relation involve social advantage and physical violence. The attitude to that violence has not softened (‘you have murdered me for centuries’).

But the poem also demands that readers recognise commonalities that are not entirely colonised by race, even if these are as small as, ‘the joy of a good piss, the smell / of fresh-cut lemon, …’.. That this commonality momentarily acknowledges that men may even love the smell as well as the joy of that piss, shows that bodies may acknowledge similarity when motivated differently in relation to each other whether in the same or different places. This isn’t to say that it’s not all about race, but it is to say that the urgent needs of the body may mean black and white bodies may in some ahistorical dream, desire each other, played out in that hidden ambiguity of come, stoop, and shoot in the last line. In that last stanza the ‘thirst’ of both is quenched.

Steve

PS. Yet again, I want to emphasise that I’m as yet in too much awe of these 2020 poems to feel I understand them. Treat the above then, as I’m sure & hope you will, as merely provisional understandings or even misunderstandings.

[1] The origin of the word for its use in black male culture is actually part of the poem, dogs! (Smith 2020: 18-22: p. 18)

[2] ibid: 67 – 70.

[3] dear white america Smith (2018: 25)

[4] Smith (2018: 49 -52)

[5] Smith (2020: 4, 25)

[6] ibid: 13

[7] ibid: 40

One thought on “Reading Danez Smith – ‘Don’t Call Us Dead: Poems’ (2018) & ‘Homie: poems’ (2020).”