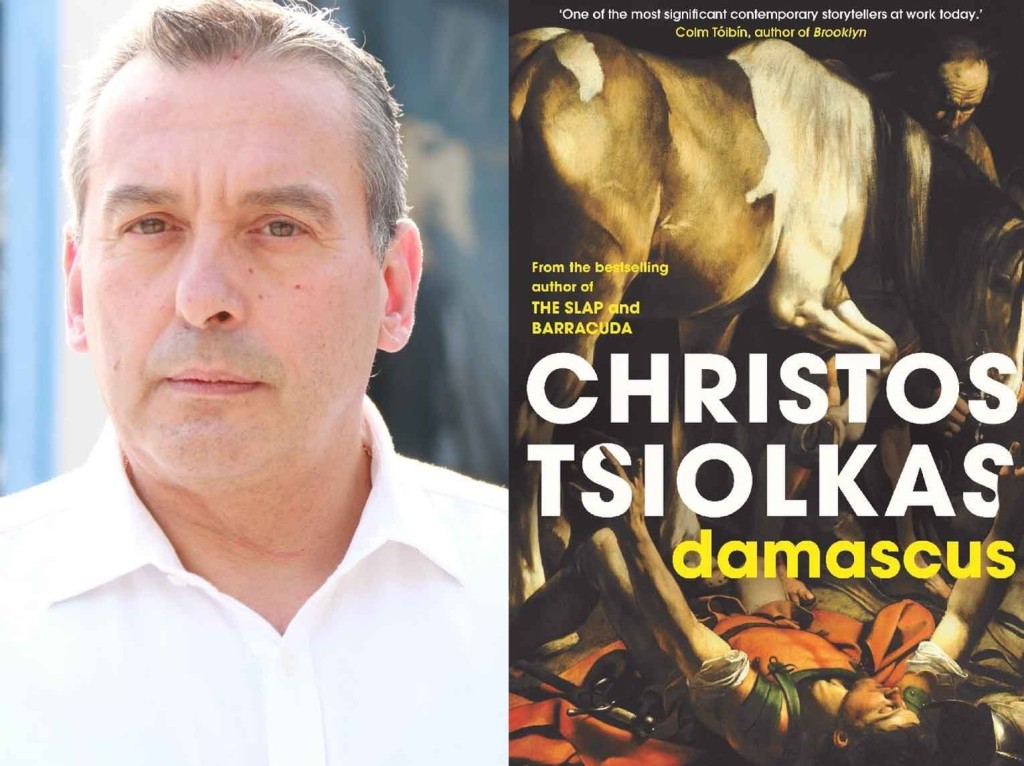

Queering the Apostolic Mission in Christos Tsiolkas’s (2020) Damascus London, Atlantic Books; “… as if there were angels in him, wrestling for dominance”.[1] Romano-Greek inheritance of Χρήστος Τσιόλκας

Section 1: Introduction: Wrestling in & with a book

Wrestling with angels is an important motif in this book. In an Afterword, Tsiolkas, speaking of the writing of the Apostle Paul (the Greek-Christian name of Saul of Tarsus) identifies him as an antagonist of his younger self. That young man aimed to ‘honour’ his own gay male sexuality in the face of the pressure of Paul’s ‘strictures against homosexuality in his first letter to the Corinthians’.[2]

Since that time I have wrestled with Paul, wanting both to honour the great universal truths that I find compelling in his interpretation of Jesus’s words and life, but also to question the oppression and hypocrisy of the Churches that claim to be founded on these very same words.

Tsiolkas (2020: 415)

I’m struck here by the ambiguity of the outcomes of the hermeneutic process applied to the words of Paul who has himself interpreted the life and words of Christ. That double process of interpretation is indeed at the heart of the novel, wherein the interpretation of the ‘life and words of Jesus’ are tested in a contest of love in the heart of the Greek youth and former boy-prostitute, Timos, who is to become the Apostle Timothy. Timothy is locked in a triumvirate (three-man love-knot) in the novel by his divided love, and theirs in heir different way for him, between Saul/Paul and Thomas, the doubter and Jesus’ own brother (for some ‘Twin’).

Whilst we might attribute the semi-unconscious match of love for Timothy to a brilliant device invented by the novelist testing his queer perception and invention against normative interpretation of sacred sources, the competition between these witnesses is historically grounded. The novel was sparked, Tsiolkas tells us by the finding of the ‘apocryphal’ (more strictly the ‘non-canonical’ since it should be seen as a text de-selected, shunned by the early Church Fathers) Gospel of Thomas in 1945 in Egypt. That Gospel valued only the ‘words and life’ of Jesus, pinning no obvious value on his ‘crucifixion and resurrection’, which it does not even mention.[3]

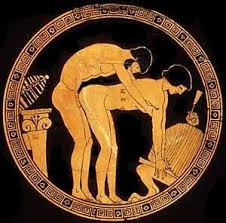

We have yet though to deal with the fortuitous allegory of wrestling in Tsiolkas’s Afterword, since that allegory emerges in the performed events and symbolic words of the novel, as men and angels together or in separate couplings pull and push each other’s bodies together and apart respectively and serially. The tradition of wrestling is very deeply embedded in the Greek-imbued Old Testament known as the Septuagint.[4] From this form, the early Graeco-Roman Church found its predictive allegories of the coming of Christ.[5] This is famously so in the story of Jacob wrestling with an Angel or God in some interpretations, on the eve of him becoming denominated Israel – CLICK LINK for contextual thoughts.[6] The importance in wrestling of tense touching as an expression of the violence of hate and, paradoxically of love (hence God’s penchant for it) and its importance in Greek and other ‘pagan’ (the novel chooses ‘Stranger’ to denominate the non-Jewish) traditions of gymnastic training emerges thus, for instance:

… “Aren’t you coming, brother?”

“Soon,” Saul replies.

But he remains standing on the peak for an age, watching the moon travel almost halfway across the sky. He gazes into the dark, his heart and spirit contorted and restless, as if there were angels within him, wrestling for dominance. One is light, eager to enter the gates of the city and breathe once more the holy air. The other is night, choosing to stay on the hilltop, fearing those with whom he was once bonded, those he considered kin and friends. He knows that many in the Sacred City do not welcome him.

When he finally returns to their camp, the fire is all but extinguished. His arms around Timothy, shivering in the cruel night on the mountains, Saul finally finds sleep. He lets the angels continue their wrestling in his dreams.

ibid: 255f.

Here the older Apostle Paul parts from Timothy whom he loves both in the spirit, but, half-unacknowledged, also in body, and which, in both circumstances in a rather complex way, constitute his nature as potential outcast from both the Jewish blood-family and Christian spiritual family to whose homes in the City he proceeds with Timothy. It is the same Timos of Lystra, his former ‘scribe’, whom had ‘saved’, perhaps even redeemed: “that boy had been lost. He had surrendered to wine, to depravity, to lust. The boy had stunk of it”.[7] I find those angels in the longer passage, heavily ‘interpreted’ (Paul’s role after all) as if they are were only an omen of his Apostolic mission to divide families but institute the Kingdom of Christ. In another layer of interpretation, the angels begin to serve as a suppressed and glorious symbol of a repressed but beautiful body wrangle with the delicious innocent sexuality represented for Saul by relationships with Timos/Timothy. It is layered allegory worthy of that of Spenser’s Faerie Queene.[8]

In what follows I intend to look at some different kinds of evidence from the novel that imply the conflictual wrestling between different value systems within it.

First I’ll look at the structure of the novel and the hints it gives of this tension between a novel dealing with two related and intersecting forms of narration. These at base can be described as a critically urgent account of ancient queer human history from a modern perspective, on the one hand, and the value-laden allegoric narrative modes that motivate narrative its ethically focused sub-sections: Hope to Faith and then Love. These are the triune Pauline pillars of Christianity in Paul’s Epistle to the Corinthians, although posed in a different sequence.[9]

Second, I will then look at how queer human history is handled and symbolised in the novel’s main characters. Focusing on the handling of the residual culture of Classical Greece and Rome, we see its contact and friction points as moments of intense wrestling between fluid queer sexualities and the birth of bodily boundaries that will be shared communally. Whilst new Christian social mores will often stand against ‘the queer’ in all its forms, I’ll suggest that we can also reinterpret the insertion of the queer into Christian history. The latter makes the former’s forms of expression and encounters softer or at least not necessarily validated by phallic ‘hardness’.

Finally we’ll consider how this theme is reflected in the socio-cultural motif of the religious sacrificial feast. I’ll look at queerness in ‘Stranger’ lore and the sacramental social feast which we know as communion, and which Strangers interpreted from the words of the Sacrament as a cannibal death cult. I treat this separately because the novel, I’ll argue, loves Paul’s teaching particularly because of the value given in it to the notion of social love, community as a product of communion and love-in-community. It is into this strictly guarded reserve of ἀγάπη agapē that we will insert male-to-male eros. I’ll deal with these under separate titles.

Section 2: Structured Motivations in The Journeys of Paul.

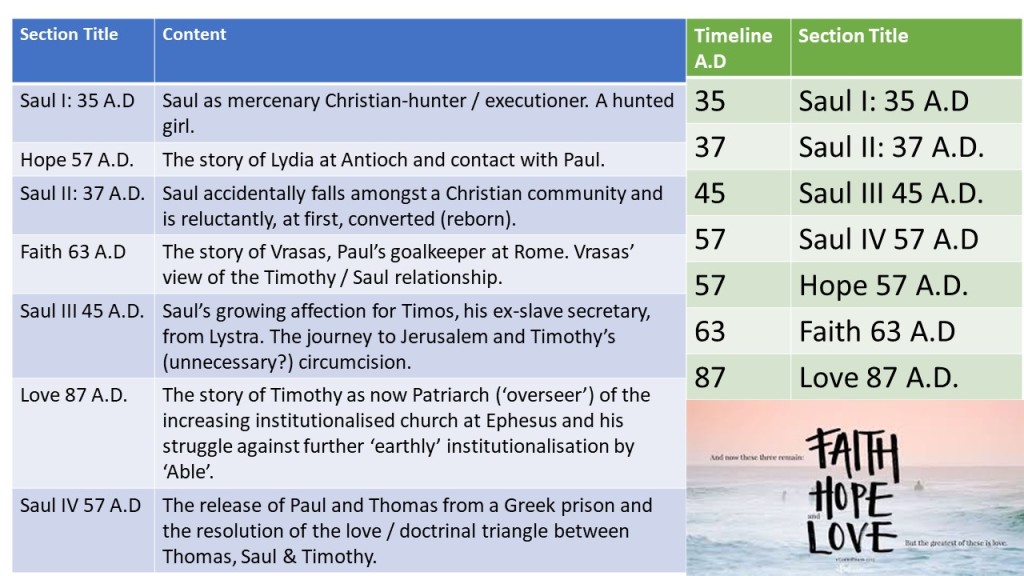

The following chart itemises the order of the book’s chaptera as they distribute between them an otherwise chronologically sequential narrative. The narrative mode of the book itself cycles forwards and backwards in time with four numbered episodes from dates supposed to be between 35 A.D. and 57 A.D. Each of these ‘Pauline biographical episodes’ is intersected by themed narratives titled after the Pauline virtues and concerning episodes in the lives of persons touched by Paul and his teaching from 57 to 87 A.D. Note that, though these virtues are not in the order they appear in the Pauline text, they do end with ‘Love’, ‘the greatest of the three’.

It was only when I devised this chart to understand the cycles in the chronology of the story a little better that I noticed that the chronology of each chapter type (if I can call them this) themselves form two succinct periods (35-57 A.D. and 57-87 A.D.). Stories on Paul’s impact on named persons cover the 20 years after the near 20 years of stories of Paul (in fact 22 years) with 57 A.D. at their joining points. I resist the view that these symmetries in chronological time, however dispersed in the shifting time sequence of the storytelling are accidental.

They insist I would argue on the deliberate patterning of episodes of Saul’s ‘life and words’ with his impact afterwards, changing as it is interpreted from a message of shared inclusive human love on earth to that message’s beginning containment in the future Church of the Early Fathers of Byzantium. Representing the latter is the aptly named ‘overseer’ of the lesser city of Colossae, the fictional ‘Able’, based partly on the Biblical Philemon. He, together with the forces assembling in Timothy’s Ephesus, begin to force the Church to take a politically hierarchical rather than ‘communalist’ form.

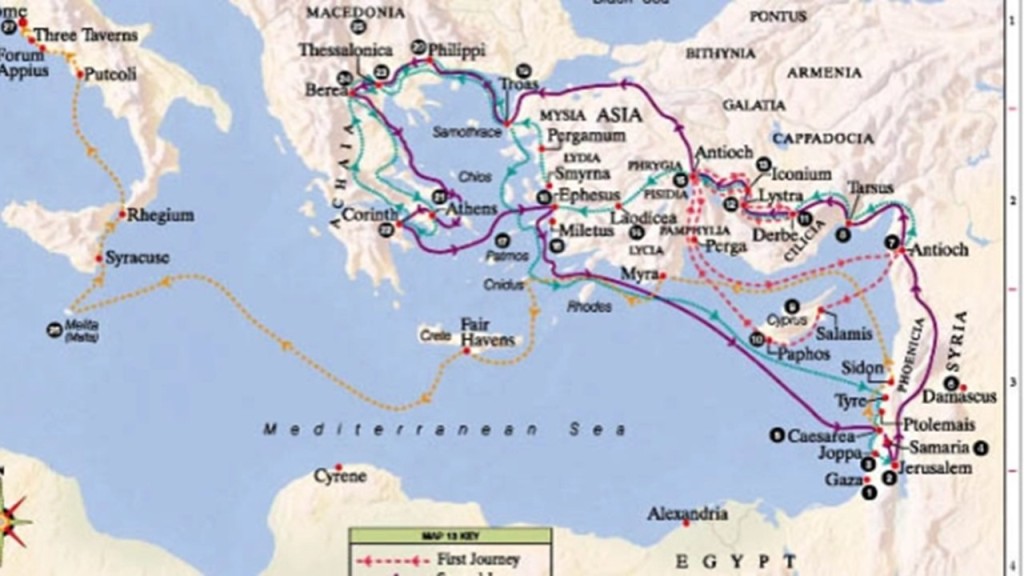

One function, I believe, of this structure is to emphasise the global reach of the Graeco-Roman Imperial world as known to people of the time. It is global as an idea of ‘Stranger’ (pagan) power asserted, challenged but to be later overthrown, at first in Rome by conversion of values-systems. This has always been the interpretation of Paul’s wandering in the Acts of the Apostles and his central role in bringing together regions in his apostolic epistles. The map below illustrates the cycles of narrative in that world.

But I’d hesitate to say that this is a theme in itself, although the fall of Jerusalem to Roman power is a lynchpin of Christian resistance and revival as a political force. It’s a background in which the theme of power is ever-present as a factor in the conduct of human relationships, interpreting what we mean by virtues such as hope, faith and love. One set of common symbols in the power of later Christianity will be shared with that of Greece and Rome: those making up a hierarchy in a real, or in christian terms, symbolic military machine. For each this military hierarchy is rooted in the principle of patriarchy: symbols of the Father, male institutions of government and, ultimately, the phallus as signifier. This story of power is crucial to the queer histories we see unfolding in the novel where fatherhood, primogeniture in inheritance, the importance of boys and their capture into ideal male forms, and the institution of a rigid code of masculinity will ride high over women, femininity, and transgressive or compromised forms of masculinity. Symbol of the latter will be the male prostitute or the passive or castrated gay male.

This is a story we have heard, of course, often. Tsiolkas mediates it through complex biopsychosocial forms – whether of overt phallic symbolism such as the Priapus which dominates Lydia’s story before she dishonours it with a transgressive touching that is refused to women, to men contemplating their own rather less grandiose fluid and fleshy penises that Thomas at one points calls merely a ‘piss-pipe’. Waking from a castration dream that recalls his ritual circumcision by Saul, Timothy is:

… mortified to find that my hand has reached down to my loins. I cup the slug that is my sex, I feel for my sacs. I am whole. All that remains of the ill-omened dream is the stink of my sweat. I rise, crouch over the chamber-pot, and release my urine. …

ibid: 288

The ‘piss-pipe’ has triumphed here over that noble organ of patriarchal power, and that is central to the novel’s overthrow of patriarchy. Even as a symbol for a queer male to male sexuality the phallus will be found inadequate since it asserts only that which centres on the social, cultural and political pretensions of mastery attributed by patriarchy to the phallus.

So why does Tsiolkas use two kinds of narrative cycle that intersect in this novel of distorted chronologies? I want to argue that this split nature of storytelling emphasises a duality in the novel’s purpose. Saul’s chronological history, and especially that important moment in the complex transformations of psychosocial queer history, whilst the other narrative proposes an allegorical narrative in which characters play many roles including those of symbolic value-systems encapsulated in words like hope, faith and love. Indeed we’ll see characters taking on these roles as moral-types, in liaison with the Christian communities who choose names for themselves like, and the best source is Lydia’s story, Clemency, Perseverance, and Temperance, and even later, as if we were falling into a Disneyworld of allegory, Cheerful.[10] The importance of Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress is of course a useful influence to remember, though its allegory is so much less layered than either Tsiolkas or Spenser achieve.

Section 3: A Transformative Moment in Queer Human History

42 was the age of Christ on his death and, perhaps except for Thomas his brother, his resurrection. The historical moments covered in the 42 years of Tsiolkas’ narrative cover momentous events that, more than the life of Jesus and career of the Christian movement, interested Josephus (c.75 A.D.) in his The Jewish War. They include the catastrophe of the fall of Jerusalem and destruction of the Temple prior to the invented events of section 6, Love, of the novel. Imperial war is often represented, in classical thought, as a higher power sodomising the lower. Saul’s brother, Barak, is not the only one to describe Roman victories over the weak as getting ‘arse-fucked’.[11]

Yet in the wider transformations of queer history this was also a moment in which patriarchal heteronormativity might be seen to be consolidated across the change in cultures that was emergent. A more complex take however would also see in Christian values the possibility of the chosen family based, not based on blood relations, but chosen by invisible links of shared love rather than inheritance, power and property. The latter might resist patriarchy and will do so in the twentieth-century. And it is this dual moment that I think emerges so beautifully in this novel. It emerges, rather than being imposed on the reader, and the manner of its emergence is contradictory at levels of unevenly shifting mutual behaviours rather than by a simple and unified pattern shift. Hence the novel remains a novel not a history.

Even in the first Chapter, Saul is our access to episodes that mark such shifts not only in behaviour but in the behaviour’s cognitive interpretation and affective impact. We approach him through the uneven and troubled development of his masculinity.

You are not a man. The truth of these words slam into him. They are right: he has no son, he has no home; as he is constantly travelling between Jerusalem and Tarsus, he is always in the keep of his sister and his brothers. He is pitiful; he creates nothing.

ibid: 16

The ‘kept man’ is feminised too by his non-generative loins, even in front of a servant boy. That moment of shame is internalised , such that Saul equates his compromised masculinity with his sexuality, ‘the depravity of his yearnings’.[12] It is clear that this includes a deeply repressed sexual yearning for prostitutes whose sex/gender is not a definitive criteria. He observes, almost as a mirror of his ‘depravity’, sex as a powerful violence (with a ‘final stab’) against subservient and invisible beings whose sex/gender is unnecessary to define:

A hairy arse, more goat than man, rises and falls in thrusting convulsions. The whore beneath him is hidden by the vileness of his exertion; whether a boy or a girl or a boy-girl, it is not possible to tell.

ibid:23 (my emphasis on the queer content)

In the queue waiting for his turn at a brothel, Saul’s sexuality becomes questioningly gay as the young man in front of him is repelled but not until that boy has found his ‘fingers tightening against Saul’s sex,’ with a ‘smile touching his lips’. Repelled violently such that the hand which ‘climbed Saul’s thigh’ is broken and surrounded by men, who well might have been up for fucking a whore of any single or transitional sex, whom are now shouting to him of the sad youth, “… finish off the dirty man-cunt.”[13]

The treatment of Saul’s sexuality will be thereafter traced in his complex relationships to other men following his conversion to Christianity and will, as the novel progresses, focus almost entirely of the drama of his all-consuming relationship with his secretary Timos, a stranger slave and former pagan ritual brothel boy, and the progress of that relationship following Timos’ conversion to Christianity and the name Timothy. This is a complex relationship, which becomes more dramatically focused when Timothy’s libidinal attachment to Paul, a strong element of his desire for conversion, is divided such that it is pulled between love of Thomas and Paul.

The meaning of this situation is even more allegorically layered because each of these love objects represent Christ and His relationship to different ritual treatment of the body in Judaic Christianity and a Christianity that has broken from Judaism. Although both welcome ‘strangers’, the love relationship of Timothy to each becomes focused around whether to comply to Timothy’s request for circumcision. Circumcision is a ritual intervention into the male body that is compared to a symbolic castration of any any male passive to love by another man. It is Paul who symbolically castrates Timothy, thus also cutting the latter off from Thomas, and this situation will later be dealt with allegorically in Timothy’s dream at the opening of Love.

We shall see that repressed sexuality defends itself by distraction, sublimation or disguise of its erotic content under the cover of everyday communal bonds. However, the boundaries between the erotic and those apparently asexual bonds that we later call agape or charity are often confused, not least by their common expression in bodily contact of hands and lips. It becomes for instance often difficult to pull apart the erotic from the expression of agape in the frequency of kissing on the lips and the focus on the touch of hands or hands and other body surfaces.

Even Able, responsible for the severest application of Christian intolerance to the unclean love of boys by men, can demonstrate this.[14] For instance in the following narration by Timothy, we sense touch is semi-sexualised in Timothy’s consciousness. However, although the thoughts and feelings of Able (who is blind and uses touch to sense others) are inaccessible, his retreat from bodily touch at the same time as Timothy seems motivated by some awareness, even in himself, of the dangers of bodily touch becoming vulnerable to erotic interpretation.

…: he has reached for my face, his touch is gentle and full of care.

“… I can feel your age, but within the blank canvas of my eyes I imagine you as I first met you in Rome.”

Closing my eyes, I too reach for his face, his shrunken and weathered skin. I force memory to return to me the image of his youth.

We abandon touch at the same moment.

ibid: 312

Timos the Stranger’s conversion into Timothy starts from Saul’s awareness of Timos’ fleshily articulated male-male sex. That fleshly sex is fluid, it: ‘oozes from loins, from between thighs and armpits, from arses: the stink of flesh’.[15] Yet Saul’s possessive love of Timothy is merely itself converted into a matter of debated theological difference. Religious charlatans are hungry for disciples and Saul realises, even if the reasons for that realisation are obscure, that: “They must not take this boy from him”.[16]

The main competition for Timothy’s love is indeed an arch-heretic, a former disciple but also ‘twin’ of Jesus, Thomas. Timothy meets Thomas in Jerusalem, where the latter resists Timothy’s wish for circumcision and hence begins a semi-theological contest for Timothy over the necessity of this symbolic ritual. It focuses significantly on the biological fact of Thomas’ ‘sex’.[17]

Vrasas overhears how Paul’s possessive and, to Vrasas’ consciousness, sexual love for Timothy in a waspish debate between Paul and Timothy, when Thomas is named by Timothy as a leader equal to Paul. Vrasas sees Paul here, as he would of course, in the sexualised satiric form of ‘an old goat’ torn by ferocious jealousy only masked, as it were, by an Apostolic purity of message.[18]

Yet for Timothy, the message of Thomas, seen as impure by Saul, is not so much to do with his millenarianism or abandonment of Jewish religious and ritual affiliation as his lack of bodily reserve with other men. Timothy remembers his stranger origins including its valorisation of the male body in male eyes, as shown in the episode in which he bathes in a pool viewed by Narcissus.[19] He takes the perspective of Narcissus in this passage.

His love of both men is however at its most heightened in the dream Timothy has opening the chapter Love, ending as it does with horror at seeing his own imagined castration. In the dream he is not merely circumcised but loses his entire male genitalia as a result of the conflict between Thomas and Saul. Thomas calls to him in mixed symbols and allegories: balancing the sexual with a more earth-bound communal love. In that dream, Thomas is a type of Walt Whitman, a type wherein age does not diminish virility as a symbol of shared love.

His smock and sandals are abandoned on the rocks and he is running into the water. He turns, naked and unashamed, and calls out, “Come, lad, come be replenished in this splendid sea!…”. I am made speechless by the wonders of my beloved.

ibid: 285

But the love offered by Thomas is also unlike that of the majority of the ‘Stranger’ societies and their gods. Timothy after all is the Christian who survives and maintains the idea of male-male Love (since this is the title of the chapter he appears himself as overseer of Ephesus) as that which survives merely genital sex.

Phallocentric sexuality in ‘Stranger’ societies is explored through the longing and Hope (the name of her chapter) of Christian Lydia for Salvation, the name given to her disabled daughter. It is also explored in terms of the witness of an endurance that is like Faith (the name of his chapter) through the eyes of the male warrior, Vrasos.

Since the greatest of those three virtues in the last named three chapters is Love, it is in the chapter Love in which it a new form for queer love and queer history is manifested. A full reading of the novel would investigate the complex layered allegories in all three chapters and their motive force towards a love based in soft touch not in the rule of hard genital violence.

Section 4: Social Communion – the blood-feast turns into a sacrament of the Body

This section extends on the themes of the last section in that it looks at how community is motivated and defined. It intends to argue that the dynamic of queer history intersects with other histories such that both the thoughts and affect that constitute queer love reflects how human histories of other kinds intersect. The rise of Christian power and ideology involved shifts in historical thinking, including those definitive of the social basis of feelings we name love, forcing negotiations, for instance, between notions of the erotic and love that sustains communion and community (ἀγάπη agapē).

In the King James Bible, this ‘love’ (in I Corinthians 13 for example) is translated as ‘charity’ which the New English Bible rejects, not least because Christianity constantly equates both kinds of love in notions of passion and ecstasy, a point especially emphasised in Baroque poetry (Donne, Crashaw) and art (Bernini). The interaction is complex and shifts between different interpretations of love. Damascus locates these problems in the shift from ‘Stranger’ (pagan) religious ritual to Christian religious ritual and the suspicious looks each give of the other in order to enforce their separation.

To illustrate how the novel deals with this I’m going to look at its interest in comparative religious sacrificial ritual. It may be possible to read the novel without noticing that such contrasts are patterned – from scenes in which animal blood sacrifice is set in proximity to, or patterned contrast with, what pagans in the novel name a cannibal death cult. This is how Strangers interpret the role of symbolic sacrifice, and consumption or internalisation of that sacrifice, in the Communion.

In fact the novel itself shows the origins of some of the complexities of the role of Communion in the later history of Christian faith – as simple memorial symbol of Christ’s death or mystery of the real presence of Christ in Communion wine and wafer, or as part of simple family worship at the dining table or an element of ecclesiastical liturgy, or, finally, somewhere in between these dual poles. The novel covers how liturgical forms for memorial might emerge as tied to an instituted and hierarchical church rather than a communal, indeed in the earliest form communist (“And all we have we share with one another”), sect or non-physical ‘family’.[20]

However, I pursue this in the novel in relation only to the links in these themes of attitudes to social rituals of appetitive desire (where food and sex co-merge in ‘idolatrous’ feasts and in the metaphorical sharing of body and blood in the form of staple foods such as wine and bread).

These themes co-exist in the time-shifts of the Joycean prose-poem given to Vrasas, the warrior and gaoler in the chapter Faith wherein sexual appetite for the otherwise untouched is violently taken and broken open (‘tight unsoiled cunts of girls’, ‘tight buttocks of the boys’). It moulds in ritual, and even ritual forms like a ‘cup’, sacrifice and ecstasy and is yet communal – about what makes the Roman individual into ‘us’, ‘we’ in the flowing pit of ‘our sex’:

…and The God is rapturous and The God is with us and The God feeds on the blood we are sacrificing to Him … and we know we are beloved of The God and this sodden pit our sex is full and we smear our sex with blood and we spill into the earth … and we raise our arms in gratitude to the sun … to The God and the blood that still pours through the slats still flowing we cup it in our hands …

ibid: 164f.

Now ‘sex’ here is not only an activity it is the name of the God in part. And that part is definitively that of value the Greek or Roman male warrior. In the story of Lydia before her conversion we are told of the sacredness of the Priapic member or phallic idol, one which women may not touch and by smearing which Lydia announces her freedom from husband, Priapus and Graeco-Roman religion. ’”Never, my child, never touch the sex of the God,” my mother warned repeatedly’.[21] She will no longer either be a mere possession amongst the economy of goods controlled by patriarchy.

Timothy later mirrors Lydia’s disrespect to the phallus.[22] Yet Timothy’s Christian community in Ephesus is still dependent on the waste food created at the sacrificial rites of the Goddess, Artemis.[23]

Damascus shows also that though the Christian rite of remembering Christ in the breaking of the bread and the sharing of wine shares at least symbolic resonance with features of Vrasos’ worship. There is ‘thanksgiving’ associated to a meal, often an everyday meal, that values and makes iconic a notion of sacrifice (and here too animals are involved if not essentially as in Graeco-Roman ritual) and valorises appetite as a feature of person and community. Saul himself sees his first Communion in a Christian community still thinking Christians, ‘drink blood and eat human flesh and thus make themselves more deranged than the Strangers’.[24] In this communal feast he is invited to ‘join’ as an act of love (of ἀγάπη) by the boy named Pup and at this early stage of Christianity it is a vegetarian feast without meat. The parallels are all there in that children, feasting and communal sharing in which children play a part but not as sexual objects:

Pup grins. “Uncle,” he says, “we will clothe you and feed you.” His eyes are blazing. “Uncle, we are full of love for you”.

ibid: 139

Sharing a Communion with the Apostle James and Channah much later, Saul describes the rite much more as a ritual of remembrance, where what is shared is not the whole social body but the ‘broken and resurrected body of the Saviour’.[25] Again though, ‘in this circle, he is loved by truer brethren.’ For me this intersects with the queer history of the book, since here too we learn to see love as less specialised than the erotic, as made up of social and socialised feeling and thought.

It is this the makes up what I see as a foretaste in the eyes of Tsiolkas’ version of queer love of the ‘dear love of comrades’ of nineteenth century USA and Walt Whitman. It is, I believe, the importance of Timos/Timothy: who as a boy is himself a temple prostitute and, as a man, he defends their right to enter the communion of Christian spirits to Brother Able.[26]

He is a man who still floats in the eye of Narcissus as an aged Christian, in one of the most beautiful and complex allegories of the book.[27] He believes in the redemption of soiled youth and even castrated youths (‘this broken body cradled in my arms smells of the Lord’), with whom also he identifies, as in the story of the defiler of Artemis’ idol, castrated by her priestess.[28] But he is also he who wishes to write a yet unwritten Gospel, one that glorifies the mix of erotic love and ἀγάπη that is enshrined, if not in the darker repressed loves of Saul, but in Thomas. Thomas is illiterate, ‘no greater than a man’, like The Twin Jesus he represents and to who no-one is not beautiful – whether prostitute or thief. The passage which follow the paragraph below has it all.

I write. I write the gospel of my lover, my friend, the beloved disciple. I write the gospel of Thomas.

ibid: 361

In the human Communion made thinkable by early Christianity (and not by its later ecclesiastical forms), there are no power differences based on class, gender, race, ethnicity, culture, physical or mental ability and, of course, of sexual orientation. In this idea lies an element of queer history we miss if we forever blame queer love’s long wandering in the wilderness to the Judaeo-Christian tradition alone. That was perhaps the Gay Liberation of my own youth. Tsiolkas rethinks it for us, in a human gospel, which is precisely what the Gospel of Thomas adds to Pauline thought, as Tsiolkas in his afterword says openly.[29]

Steve

[1] Tsiolkas (2020: 255)

[2] ibid: 415

[3] ibid: 416

[4] my source is Brenton, L.C.L. (1986 – first printed 1851) The Septuagint with Apocrypha: Greek and English Peabody, Mass., USA, Hendrickson Publishers Marketing.

[5] Dines, J.M. [Knibb, M.A. Ed.] (2004) The Septuagint London & New York, T&T Clark Ltd. p.143.

[6] For the comprehensive background see Hayward, C.T.R. (2005) Interpretations of the Name Israel in Ancient Judaism & some Early Christian Writings: From Victorious Athlete to Heavenly Champion Oxford & New York, Oxford University Press

[7] Tsiolkas (2020: 242)

[8] “So while The Faerie Queene is absolutely an allegory, it’s a complicated allegory. Indeed, some people have read the poem as—get ready for it—an allegory of allegory itself. … The Faerie Queene is a poem that is thinking through the very nature of allegorical meaning, literary meaning, and the power of representation. …” in https://www.shmoop.com/study-guides/literature/faerie-queene/analysis (I’ve chose a very low-level explanation on purpose. Why not! (Free of stuffy academics now).

[9] I Corintians 13, v.13: in the New English Version of the Bible ‘And now these three remain: faith, hope and love. But the greatest of these is love.

[10] Find the first three names on pp. 89f., the last lives in Timothy’s Ephesus community.

[11] ibid:18 but the term will be found throughout

[12] ibid: 20

[13] ibid: 24f.

[14] ibid: 309. Able reprimands Timothy for consorting, and converting, working temple ‘whores’ (of all sexes).

[15] ibid: 243

[16] ibid: 247

[17] ibid: 258-263.

[18] ibid: 223

[19] ibid: 365

[20] ibid: 138

[21] ibid: 39

[22] ibid: 345

[23] ibid: 295

[24] ibid: 136

[25] ibid: 273

[26] ibid: 310f.

[27] ibid: 364f.

[28] ibid: 355

[29] ibid: 419

One thought on “Queering the Apostolic Mission in Christos Tsiolkas’ (2020) 'Damascus'; “… as if there were angels in him, wrestling for dominance”.”