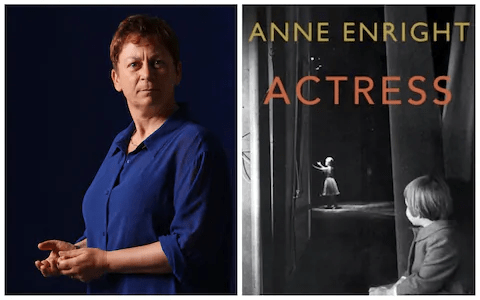

Performed emotion in Anne Enright’s (2020) Actress London, Jonathan Cape; “… never the same show twice. Othello, Trilby, Oedipus: jealousy, incest, blood and desire”.[1]

I seem to remember that, in a BBC TV programme about one of Colm Tóibin’s family drama novels, Enright comments that it is a great pity that the rest of the world relies on Irish writers to produce such dramas: ‘they should write their own’. Maybe, disappointed in this wish, she has now written an international family drama in which the emotions of family life, even those of national identities become part of a much greater drama that co-defines both drama and family. This novel does not challenge in my mind the superiority of The Old Road as the brooding novel of West Ireland, and of the Burren in particular, but its ambition is, in many respects, the greater.

It focuses on the idea of performativity as the source of identity and meaning of objects, on the one hand, or reflexively, on the other, those subjective thinking imposes on itself. This is so, even when identities or meanings vary, retain static rigidity or do both in either sequence or simultaneous interaction.

In the simplest sense, it starts by considering what it means to enact a role. Hence, taking the history of a family who tour plays. For these characters, the meaning of their behaviour relative to each other is constantly adjudged on a scale of relative sincerity from ‘fake’ to ‘real’. But even the mix of ‘characters’ in Actress is fake and real: making that point, with some stunning effects on the use of real-life characters such as Stephen Spender, Bryan Forbes and Dennis Laughton.

Where, even here, do real and fake begin and end. Performance straggles the theatrical and the lived ‘reality’ with no discernible boundary for the ‘actor-characters’ as they see each other in both contexts. Summarising her grandfather’s later life as a failing film actor in 50s British films, the narrator, Norah, says:

He is playing the bluff old general, or the pipe-considering RAF colonel who crosses out the lost planes on a chalkboard. He is the coward, the liar, the one who makes the wrong decision and walks off screen contented. It is something about the mouth perhaps. Fitz spoke like a fake, and you might think this was acting, but he spoke like the same fake in every role.

Enright (2020: 41f.)

In the ‘role’ of a father too we shall observe a source of tainted power and authority, wherein masculinity exerts and interprets itself all of the time as a source of security quite contentedly, whilst actually doing little but marking of the losses that other people then suffer.

That wonderful neologism ‘pipe-considering’ does a lot of work here, from catching a stereotype of 50s war films to characterising male dependence on a ‘pipe’ to act, as it were, for them. Yet discerning what is real in each and every role is difficult – performance quality and its efficacy being our only standard. Pleasance tries to save the young Katharine later, ‘from doing weird scenes with her father’. Oedipus is on the bill. Incest is one of the shows that the playlist must comprise: ‘jealousy, incest, blood and desire’.[2] And chief enactor of the Oedipal Father is the priest, cum psychoanalyst, Father Des, who enacts both roles whilst abusing Norah’s mother. This is in a novel where otherwise, sexually abusive priests are only referred to decorously.[3]

The performance of other roles is equally complex – both a disguise and a reality. Mimetic performance is something one sacrifices only for a poor audience: “Provinces only dear”, as Katharine’s father Fitz says of his Irish tours, when he shuffles roles of director, actor and stagehand on-stage. Marriages are enacted events such as that between Norah’s mother, Katharine, and her gay husband, for all intents an purposes enacting too the role of Norah’s father, Philip Greenfield. After Katharine enacts an Irish nun, Sister Mary Felicitas, with apparent disregard for an audience, being, as it were, the role, she must take a curtain-call, entering meanwhile a liminal space, ‘still between’ the things she is:

… she is still between things, she is coming back to herself, seeing that she is dressed, for some reason, in nun’s clothes.

It is all so very surprising, Oh, there you are, a hand at her breast. It looks quite fake, but I think it was entirely real.

ibid: 89

And even Katharine’s Irishness is fake – coming from a change of punctuation from an English family name, Odell, to the stagey Irish of O’Dell.[4] Fake or real? Perhaps fake and real or, as in that innocent phrase above ‘still between things’ where only how you perform and with what pre-existing script, cast-list, and stage props, even a gun (a very major fake or real prop), makes the difference between what is fake and what is real, if difference there be. Another paradigm of the book lies in the phrase ‘give and take’ and the novel is full of instances of its use where an action slyly means its opposite, as in the sly use of the ambiguity in the word ‘take’ used in describing her film-acting style:

… unfailingly, she hit her mark, found her light, saw herself as she was seen by the lens, and gave, with every take, some new or useful variation on the last.

ibid: 97 (my emphasis)

Performance is itself a balance between what is given to a role and what is taken by the role’s audience. In sexual actions, the imbalance can heavily weigh in favouring the more powerful person in the interaction who takes more than they (usually, in this novel, he) ever gives:

Who told me this (apart from everyone?) – that a man takes his pleasure and gives only pain. … This is what you get for wanting.

ibid: 133 (author’s emphasis)

Families are ideal scenarios for the enforced enactment of sincerity or other appropriate emotion: ‘She broke the news (of grandfather’s death) like a good mother. …. I was supposed to be sad, so I sighed’.[5] And this does not apply only to ‘acting’ families like those depicted in this novel: perhaps all families, that is, enact ‘family dramas’. The phrase is somewhat indicative. Katharine’s girlhood girl-love in a theatrically symbolic family troupe, Pleasance, is spotted at Katharine’s funeral, now married to a Coronation Street director, but isn’t, at first, recognised:

She was not an actress, clearly. She was the kind of woman an actress would imitate but never be; ash-blonde hair, stiff with spray, good camel coat, black patents with two-inch block heels.

ibid: 77

Pleasance was an actress and, perhaps, in one of the sly ironies of the prose still is, acting that which is not acted (or should not be seen to be if its effects on audience perception are to work) replete with costume appurtenances that scream out a ‘fake’. And perhaps being fake is what not-being as an actress is. Perhaps the question asked most often of Hamlet, is ‘his madness fake or real’ can also be applied to Katharine O’Dell provided we expect a complex answer that is neither, ‘yes’ or ‘no’.

Funerals too are enacted events and contain a whole lot of generous giving and selfish taking if they, and their absent subject, are to be appreciated. Showy? Yes. Is not all emotion, fake and real, a ‘show’:

Actors spend their lives stalking and catching their fugitive sorrows. They do this in all generosity, because no one cries alone. An appeal for your tears is also an appeal for justice: it releases the healing power of the crowd.

ibid: 260f.

The tone in which Katharine’s funeral is recorded by her daughter as a narrator is incredibly hard to catch. We have what feels like irony, meaning the opposite of what it performs, and yet forever attempting to rescue a more redemptive kinder meaning that justifies its characters as something other than ‘seemers’, to use the word from Hamlet.

And this is so because writing and reading are occupations both requiring constructions of meaning. They are also enactments that can the more easily pretend to authenticity. Norah makes the point frequently that she is not an actress of this novel. Her performance is best as a reader and, in the making of this book, writer. And sometimes we are tempted to see through her just when she is engaged in these actions, even if only because she protests her innocence so much and manages to ‘pretend’ therefore unnoticed.

‘You stick to the books!’ my mother said, looking at me …, as though I had done something wrong, or was just about to.

Which I certainly was not.

… Besides, if I pretended not to be listening, there was the chance I might hear some more, …

I always felt safe on the page.

ibid: 70 (my omissions)

There is safety sometimes in the narrator’s pretence to transparency in recording the actions of others but sometimes one can be caught out. You, like I, may feel, as I do, that Katharine, the observed subject of this biography, is sometimes a means of helping us to look at Norah with a keener eye, making her position less ‘safe on the page’, unearthing her own implication in the tragedies unfurled. That is why I think ironies in this novel are complex.

Is Actress an enactment too of the Irish ‘family drama’: if so it is enacted to expose its fallacy of financial security and safety from the most gross predation. It, like the Catholic Church in the novel, is something replete with the fake and the real. Anne Enright is an extremely wonderful writer – exposing narrative performance, even in the virtue of wondrously beautiful sentences, as precisely that – an enactment of the real, the fake and that domain ‘still between’ both. The ironies of the novel are at their most complex when they deal with Irish Politics following Bloody Sunday and the ongoing Troubles over the Northern Irish border.

But the novel sometimes seems to suggest, or is it rather Norah who does this, that Katharine’s empathy, perhaps anyone’s empathy, for the IRA is kind of ‘fake’: ‘Irish for love, she was also Irish for money’.[6] That could have been what the novel was saying, going against the reasons why the IRA has come back fully into Irish politics, were it not that it also makes it clear that Irishness is not just family drama and Ireland is more complex than a family.

It is also a political struggle, performed more earnestly and as a matter of life and death. Perhaps the finest way of capturing this in the description of a Dublin bomb, where the decapitation of a young woman by a bomb gets mired in the drama ensuing of a man laying his coat on the body, only in prospect of being questioned by a disbelieving wife.[7]

This is a very great novel indeed. No-one will ever say it is another Irish ‘family drama’, since family and drama are themselves part of examined in an area of liminality and uncovered as real, sometimes fake and often ‘still between things’

Steve

[1] Enright (2020: 39)

[2] ibid.

[3] ibid: 61f.

[4] ibid: 25

[5] ibid: 126

[6] ibid: 131

[7] ibid: 162