WARNING: Contains spoilers. For short account of Forum Bookshop account see: https://stevebamlett.home.blog/2020/02/19/reflecting-on-the-author-talk-at-forum-books-corbridge-18th-february-2020-7p-m-deepa-anappara-2020-djinn-patrol-on-the-purple-line/

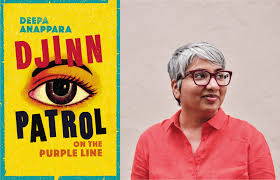

Reflecting on a debut novel by Deepa Anappara (2020) Djinn Patrol on the Purple Line London, Chatto & Windus. Prior to seeing the author talk at Forum Books, Corbridge 18th February 2020, 7p.m.

Anappara speaks very usefully about her debut novel in an easily found piece from United Arab Emirates’ The National. In this piece, she justifies her choice as narrator of a nine-year-old boy, Jai, from a tense, religiously divided and marginalised working-class community enveloped in smog, in part, thus:

In Jai’s community, that plays out in a belief system that allows for ghosts, djinn and spirits. Hence the book’s title.

“I see this in my own life all the time and it’s so integral to so many communities,” Anappara says. “You can be a firm atheist, even, but when you’re in a challenging situation and have nowhere else to turn, I think you naturally find solace and comfort in a kind of supernatural storytelling. That very easily comes into play in a situation you can’t control or comprehend.”

https://www.thenational.ae/arts-culture/books/djinn-patrol-on-the-purple-line-why-deepa-anappara-s-debut-is-about-children-not-for-children-1.979323

These features are structural as well as part of the novel’s themes: especially that of how human beings come to terms with change, a range of losses (even the most personal and poignant) and the problem of the apparent endless and often uneven battle between evil and good in the motivation of all-too-human actions. It is in 3 parts. Each part is prefaced by a chapter named, ‘This Story Will Save Your Life’, and each of these focuses particular needs served by semi-religious and ‘supernaturalised’ belief systems.

The first story tells of the genesis of a ‘myth’ of the ghost, Metal, whose real name is unknown but to his original community of semi-dependants and is not shared with us. He is a kind of pimp but his meaning spreads from an inexplicable good in his behaviour to his boys to something apparently transcendent. The second tells of Junction-ki-Rani, whom the young Muslim Kabir tells his equally lost sister Khadifa (as both wait unknowingly for predation by adults): “She protects girls”. Unconvinced Khadifa indicates that both Metal and Junction-ki-Rani protect only Hindu boys and girls (Anappara 2020:257).

A page later we get the third ‘This Story Will Save Your Life’ (ibid:261ff.) chapter in which a specifically Muslim supernatural source is regenerated to explicate how we might look for safety for all children, in the temple of the djinn-saints.

Otherwise the title chapters are the first part of the first sentence of the chapter into which they run on. This can create some quite varied ‘enjambement’ effects. For instance, look at this one:

Tonight is Our Last Night-

-in the basti, Ma says. No need for this drama-baazi, Papa says. ….

ibid:55

In a novel so full of departures and sudden deaths and disappearances, the title raises expectations that fall into bathos in the run-on into the chapter; an effect Papa frames by comment that serves to illuminate the ‘drama-baazi’ the prose has played on us. Otherwise run-ons, and probably in the majority of cases, have no great role in the meaning other than to differentiate them from the ‘Save Your Life’ chapter for each Part of the novel and intersected chapters named – without that name being absorbed into the first sentence – after the child or children whose disappearance-story just prior to their taking is told therein.

These structural characteristics tell us a lot. The novel is about unthinkable loss – the disappearance and possible and imagined death or enslavement of very young children – which is entirely irreducible by the stories we tell to redeem the fact of that loss. For Jai, these are initially detective stories picked up from a TV series he names Crime Patrol. I feel no certainty than any life is redeemed by the ‘Save Your Life’ stories – their making is often in great tension from the realities they arose from. And some other supernatural stories in the book, particularly of the djinns are irreducibly of evil, and nearer to the gruesome truth about the capitalist enterprise built on child-stealing and trafficking. Some are quite comically told as in Jai’s belief that traffickers, ‘turn children into bricks,’ (ibid:111). Others are nightmarish:

That night I dreamt of child-legs and child-hands hanging out of bloody mouths and then I hear fighting voices.

ibid:229

In that dream – and we say to children internationally, ‘It’s only a dream,’ to reassure them – issues like the kidney trafficking business, involving the waste disposal of other body parts, are prefigured. When they come they are unthinkable and we have perhaps, as Jai does (ibid:341), to return to the supernatural for comfort or even the maintenance of sanity.

In our prior quotation from the subtle prose of this novel, the nightmare child-eating djinn metamorphosises to parents having a fight over rusk breakfast. There are so many places in this novel where we see adults failing children, whom they claim to care for – and these include, but not exclusively, parents. Thus the first lost child, Bahadur, is taken after thinking, in a quite unrelated way, of the inadequacy of a father so drunk: ‘such that he couldn’t tell flesh from shadow’ (ibid:49-51). The second child, Omvir, welcomes what will turn out to be his murderer: ‘because he wasn’t his father, in that moment he also felt hope’, (ibid:96). Most moving of all is the story of Runu prior to disappearance, whose difficult life takes in the inadequacy of parents, and particularly males (even her brother Jai):

… a man needn’t be soused up to the eyeballs like Drunkard Laloo [Bahadur’s father] to be a bad father.

ibid:283

But I do not think this is just a man-blaming novel which stops in finding fault inside the poverty of Indian working-class communities. Interestingly real evil is probably focused (we sort of think she’ll wriggle out of it in fact) in a rich female entrepreneur who manages to shift blame onto her henchman. She receives no roundness, in the E. M. Forster tradition, because (I believe) there is no such roundness in people capable of the conscious transformation of even working-class children into commodities. Moreover, Runu’s father is not only described by Runu in the novel.

The story is in part architectural and tells how the labour – male and female – of those living in the ‘basti’ (knocked up suburban housing that can easily be knocked down in a day by a JCB) is exploited. Take this beautiful Dickensian passage, telling of a modern city suburb in emergence:

The earth twitches as a metro train rumbles underground somewhere near us. It will worm out of a tunnel, zoom past half-finished buildings, and climb up a bridge to an above-ground station before returning to the city because this is where the Purple line ends. The Metro Station is new, and Papa was one of the people who built its sparkly walls. Now he’s making a tower so tall they have to put flashing red lights on top to warn pilots not to fly too low.

ibid:13

The very earth itself is like a body feeling its own dis-ease – cut out in the passage in metaphors that negotiate the mechanical and organic (such as the worm). The sparkly opulence of the hi-fi (high finance?) life of the rich, for whose needs alone this city exists, we will see again as the murders are uncovered but is built by and on the bones of poorly rewarded labour – on Papa, whatever his faults as a father. This novel in fact shows failed fathers redeemed by their transformation into absolute wreckage by the loss of their children, although this too has the effect of causing further hardship for dependant children and even lower-paid women.

If the hi-fi city is the world of the rich, the market, with its piles of offal and bleeding severed goats feet is the place where life in poverty is lived. Much more could be said here by looking at some of the sumptuous but understated prose of the market pieces. However there is third locus of importance in the city – discovered in full for us, for the first time by Jai’s wonderful dog, Samosa.

This is the garbage heap. A place where the inevitable necessary waste of a capitalist society finds its unregulated and undifferentiated home. For waste heaps, we shall see, can include not only old or decayed meat but child-body-fragments. Waste is inevitable – its decay of dead unwanted alimentary pieces and the stench exuded offends both poor and rich and neither can escape it (ibid:141).

This is the truth of the capitalist system and its reliance on values set by the market. Those latter give financial value to a kidney of a child, for instance, but not other body-parts. It is this system which is the human-hungry djinn patrolled by the Purple line. It eats ritual too – the most moving example of which is the beheading of the revered buffalo bull, Baba.

Because the subject is emergent modernity, we see it as a product of a history in which that modernity rubs shoulders with remnants of older cultures in decay. But the novels themes cover much besides class and money. The treatment of the role of women in Indian society is wonderfully handled. Although it gets under-stated by the author choosing the perspective of a male who at 9-years-old, one issue is that we know that he, though younger, has much more projected social status than his sister.

The novel further treats of the social perception of women, and its very practical effects on the lives of developing girls is told through the story of Aanchal. Because she is taken, she is inevitably rumoured to be a prostitute, leading our boy detectives to a kotha (brothel) to find her. In fact the character we get to know is trying to climb out of these lower expectations imposed on her by others through education, much as Runu hopes to achieve as a relay-runner. She knows that she is misrepresented by people who ‘disassembled her character with the viciousness of starved dogs chancing upon a scrawny bird,’ (ibid:171)

Characters in novels get disassembled in order to fit stereotypes. The latter ensure maintenance of power divisions between classes, genders, and (sometimes as a symbol of the other divisions) between humans and animals. A major concern in the community is the division of Hindu and Muslim in India and the novel shows how partition of communities too is an invention of power struggles rooted in the need of one community to find its main enemy in an easier to comprehend scapegoat. Hence the Hindu Samaj gets turned into a means of using loss, even from Muslim communities, to justify political apartheid. In the light of this theme, the end of the novel is truly tragic as religious grouping blame the other for the existence of a more real and material evil.

You may have a minor issue with the books language. I think though potential readers might gain confidence from knowing that I, at least, may never have been certain of the meaning of many words in this book which, in all probability, come from dialect forms or modern neologism but could still manage it. For instance, to take a page at random at the price of appearing totally ignorant, I was unsure if my guesses of word meaning from the prose context really understood what all of these words meant in detail: such as dhaba, puja, pandal.

Now, internet searches are good but not always accurate. I’m still pleased though that British publishers do not now, as they did once, provide glossaries for novels by Indian authors. What that means here is that there may be areas of nuance, in terms of social and cultural placement English monolinguals miss. But that is life. To illustrate one effect I want to use a passage using the term pakka (use link to get a glossary substitute searched in a wiki on the internet using a number of languages). The UrduPoint website translates it, from پکا, as ‘confirmed’. Now let’s see the passage:

No one will believe me but I’m one hundred per cent pakka that my nose grows longer when I’m in the bazaar because of its smells, of tea and raw meat and buns and kebabs and rotis. My ears get bigger too, because of the sounds, ladles scraping against pans, butchers’ knives thwacking against chopping boards, rickshaws and scooters honking, and gunfire and bad words boom-booming out of video-game parlours hidden behind grimy curtains. But today my nose and ears stay the same size because Bahadur has vanished, ….

ibid:23f.

Now there may be resonance between the unitary translation ‘confirmed’ from UrduPoint with the other meanings of pakka, in Marathi, recorded in the wiki. I wonder about those meaning such as ‘brought to completion’ or ‘cooked’. I cannot know. However, where there to be such resonances there would be a much enriched reading of the passage.

It is not only that Jai is certain (confirmed) that his life expands in the bazaar, but that it expands through the senses once they take in and cook the edible smells and cooking sounds, all mixed with the everyday processes of living. Those definitions mean pakka might convey more within its context than it does to me, at least without further knowledge.

If this is so, it means that there are other unfolded riches in this novel than that available to the monolingual reader, which in effect (despite smatterings of French and Greek) I am. That is wonderful because it means that this novel might have a readership that has more importance than the monolingual English reader and that the power relations in reading for people of South Asian origin are reversed for one moment in time in this England now. Good!

Perhaps though I could finish on a haunting feeling I have about the import of Dickens in this novel, especially in the way in which the symbolic importance of ‘fog’ in Bleak House resonates with the ‘smog’ in this novel. Both have a post-industrial and industrialising social presence. The smog in our novel lifts only with the end of a winter holding in the effluence of capitalism and in it, Jai finds a kind of salvation which transcends the old divisive gods of divisive communities, His dead sister is a star:

She’s watching over me the way Metal watches over his boys, I just know it.

Then I see the star again. I point it out to Samosa. I tell him it’s a secret signal, from Runu-Didi to me. It’s so powerful, it can fire past the thickets of clouds and smog and even the walls that Ma’s gods have put up to separate one world from next.

ibid:341.

This quasi-apocalyptic vision is aimed as much against the smog that divides us and stops us seeing the common enemy in capitalist values, as is Dickens’ foggy unreal world of false values about relationships enshrined in the economy and legal system. Smog is that which blinds perception (ibid:14), promotes the performance of sadness in families (ibid:20), hides danger – even djinns or child-traffickers (ibid:37), is cold evil itself (‘the devil’s own breath’ ibid:52), and brings together hidden evils like garbage tip and the hi-fis (ibid:141). One of my favourite examples employs one of the run-on titles I wrote about earlier:

The Basti is Losing its Shape-

-in the smog when we get out of school next day. …

ibid:159

Again like Dickens’ fog in the opening of Bleak House, smog cause shape-shifting and links to the shape-shifting capacity of djinns referred to throughout the novel. And shape-shifting is one of the functions, as we know after Marx, of money too as it makes equivalent disparate goods through exchange, even kidneys wanted by the rich and still in the possession of the poor to whom they have no monetary value. I have a feeling that this could be recognised as a very good novel of symbolist-realism that might evoke not only Dickens but Zola. Anappara’s resource list shows how far such readings might in the future be productively taken.

Well. That is what I think of it.

Steve

One thought on “Reflecting on a debut novel by Deepa Anappara (2020) ‘Djinn Patrol on the Purple Line’ London, Chatto & Windus.”