Reflecting on Jenni Fagan’s ‘Pluripotent’: A short Story in Sabrina Mahfouz’s (ed.) anthology (2019) Smashing It: Working Class Artists on Life, Art & Making It Happen London, The Westbourne Press, pages 104 – 109.

This is a fine book and I’d recommend every piece in it. It tries to think about how life and art are both made from diverse experience of being working class, often intersected with other identities which interact with the experience itself.

This involves no simplistic definition of class. Making art can make life happen in different ways: many writers refer to the problem that artistic success can compromise one’s personal understanding of your own life and art and may change reflexively how we experience ourselves as working class. Joelle Taylor’s piece ‘Smashing the Class Ceiling’, for instance, appears aphoristic in a fairly simple way but it is anything but. This is because a class ceiling is not a glass ceiling except in the echo evoked by the phrase. When we smash through the former, the world looks different (even in developing and working with our attitude to ‘Money’, which Bridget Minamore explores).

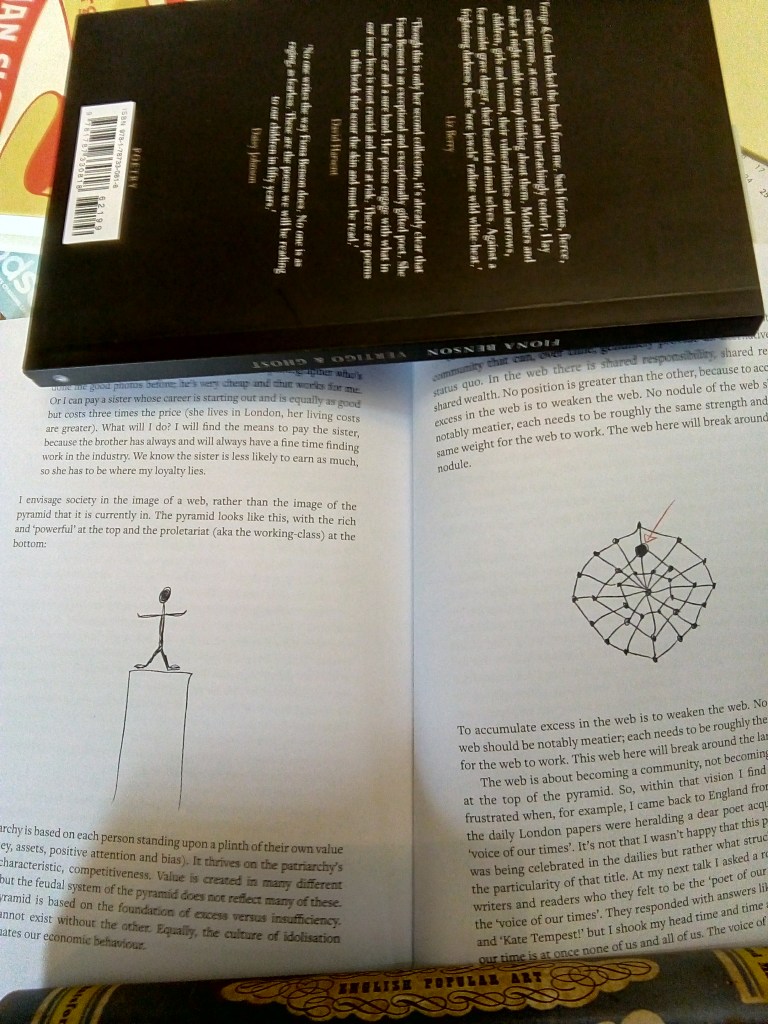

Even if we look ‘down’ to whence we came, we know we have to learn not only to rise through it but to demolish its demand on us to change ourselves. We must not act and think as if the world above the ceiling for the working class is now the only world that matters. Even as they laud you it hints, the middle class sustain your limitations if you do not change only yourself and don’t carry your class with you as the effective basic construct of your being. This class-based construct is that of a collective network not a modelling plinth for one’s own individuality. Linda Luxx helps us to understand that by drawing pen diagrams of an ‘economy of sisterhood’ against more conventional models of living class metamorphosis that are reproduced in the book

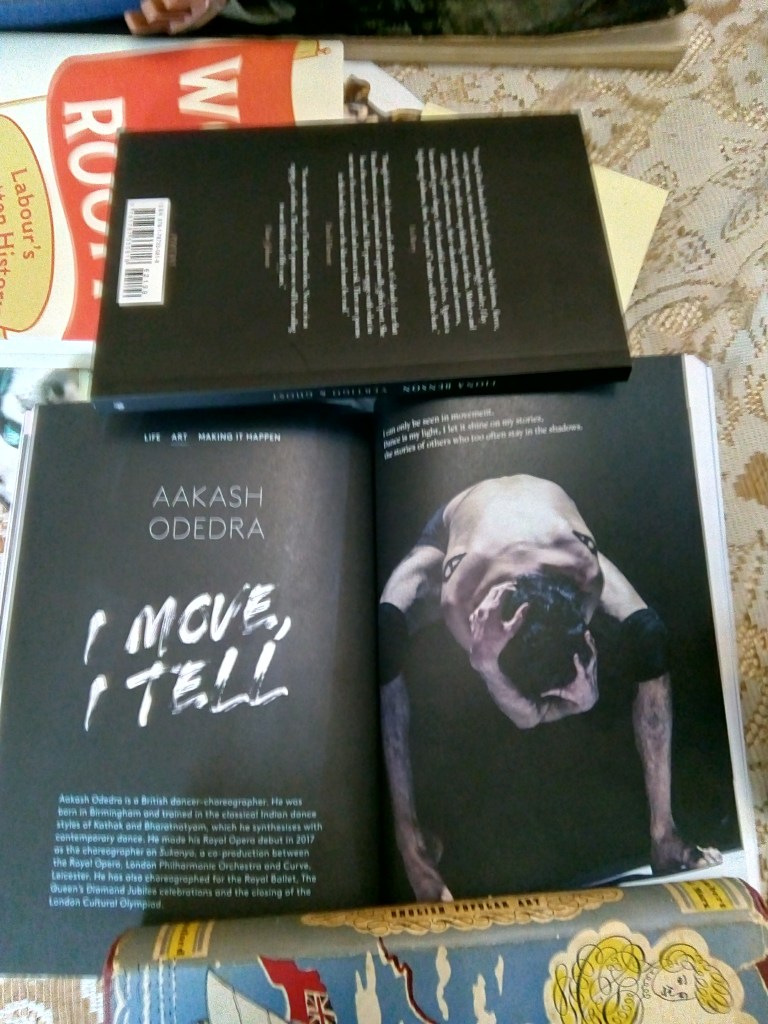

Once we have taken on the lessons of smashing the class ceiling, the contribution of working-class experience in art is less easy to discern, and certainly less easy to stereotype. Do not, though, expect all of these writers to have found the same, or even similar answers. Some merely puzzle over the metamorphosis in class even though all see it as necessitating a return to something fundamental. How class speaks in the world of a dancer-choreographer may remain elusive as you ponder Aakas Odedra’s stills from his performances or his short poems:

I can only be seen in movement,

Dance is my light, I let it shine on my stories,

the stories of others who too often stay in the shadows.

p. 201

Here, class is the otherness of transitional movement out of which the liminal to hegemonic culture arises: ‘others who too often stay in the shadows.’

My aim though is to look at a short story from a writer who has already found success but, with it, has found new questions. Jenni Fagan has said on Twitter that this is an old story that she has recently revised. It would be fascinating to look at the revisions and see in what ways the changes reflect new thinking. However, that is not what this is about.

The story takes up a theme found throughout about the nature of working-class language and the forms it embodies. It focuses on the consciousness of Louise, a working-class girl on the cusp of 13 who loses ‘her virginity’ one night to a ‘cherry-hooked closet-junkie prick’.

Since her consciousness is revealed in third-person narration, her language fades in and out of the narrative voice. In the opening the narrator continually keeps distant from any attempt, for instance, to reproduce what we might think of as Louise’s own syntax. This allows the narrator to place Louise in more than one discourse – one in which she might think and speak and one in which she is spoken about.

Such dislocations are central to the way working-class language can be subordinated to the language of a bourgeois literary, and perhaps ethico-psychological discourse. This is the problem in Scottish fiction that James Kelman has been attempting to avoid all of his literary life. But sometimes when the subject is still working-class experience we can’t avoid its lingering presence. For instance, look at the elaboration of Louise’s feeling that this sexual experience was ‘shit’:

It wasn’t shit because she didn’t wait to do it with someone she loved, or someone she felt comfortable with, or even knew, for that matter. Louise doesn’t give a fuck about any of that bullshit. She has observed the so-called adult world for years and has no delusions regarding happy ever-afters, movements in the Earth or any of that other crap. It was shit because he filmed it and he never said he would and after she stood up, she felt like a bit of his thing had fallen off and that it was still in there. No-one told her that happened. …

p. 105

The language here is so hard to place. We can’t. or shouldn’t assume that the vocabulary and the syntactic organisation isn’t not hers but there is a good chance it isn’t. We are accustomed to our literary heroines having the play of a narrator’s irony over their thought or feelings. This helps to place the character in a moral world we do not presume she yet inhabits.

Hence, Louise herself may never even have thought that her ‘sexual experience’ lacked expectations of love or comfort or that that was an abnormal experience. She may have thought these ideas were ‘crap’ if proposed to her, but the prose does not demand that she has thought about them here – indeed these are merely potentially expectations the narrator shares with her reader to further place her character in terms of both her age and class. Hence reading this is also always an act of class consciousness, where the working-class or otherwise ‘deficient’ character is subject to a normative discourse to which she has no access and to which she may desire no access.

So who then, as we read, has ‘delusions of happy ever-afters’. or ‘movements in the Earth’ in these sentences? Those delusions only securely belong in the world of post-13 accustomed readers acculturated to normative expectations of literary romance either in narrative forms (‘happy ever-afters’) or romantic trope (movements of the Earth being the trope from Hemingway’s For Whom the Bell Tolls) that has passed into even anonymous, if class-coded, discourse.[1]

So Louise’s language is not what we get here. Louise is, I would say, made to some degree, but the extent will depend on what assumptions we make about such language, subordinate to the language of literary description – an object that such discourse places in its own tropes for understanding the world.

The beauty of third person narration is that it can continually inhabit not only what she thinks but how she might linguistically express that thought-content. Let’s take this

The lead weight in her spine gets more intense the nearer to school she gets, until she feels her back must be stooping and people in the street are probably staring more than ever because she is obviously a total freak.

p. 106

When I read this I accept the metaphor of the ‘lead weight’ as an expressive strategy of which I don’t need Louise to be conscious, although the ‘probably staring more than ever because she is obviously a total freak’, entirely demands that we see in the syntax and terminology of those phrases a mimesis of her own language. It is, after all the weight of ‘obviously’ – a kind of projection using an over-self-conscious and emphatic language of a self-centred very young girl in that situation that she casts into judging eyes that may have been of her own invention. It shows her feeling marked by the gaze of her own lack of self-esteem. Even more so we see this in the following paragraph, where the narrator lets go of any super-authorial control of her character’s language:

The three girls in 2c that said they’re going to kick her head in and film it ‘a la happy slap’ for complete humiliation factor are standing by the school gate smoking.

ibid.

Now this sentence gives us narrative content in telling us why each of the characters are in the imagined spaces of the story but its main purpose is to show what Louise fears in this confrontation and why. The term ‘complete humiliation factor’ bears the register of the girls’ own talk – what both victims fear and perpetrators set out to enjoy seeing in their victims. This is not the language of the literary narrator.

Of course, all I’ve illustrated is the potential of third-person narration to expose the character’s own thought and evaluation systems or to invoke a thought and evaluation that can exclude her, to mark the characteristics perceived not only of her self but those characteristics, nearly always seen as deficiencies, of the whole class and category from which she comes.

Without the radical experimentation of Kelman, working-class writers can be trapped in showing the origin of their specific lives and the life of their especial content as if it were always deficient. Moreover, the standard of judgement is always assumed to be that of the middle-class literary tradition. This returns, for instance, in descriptions of schoolgirls such as this:

They arrange themselves on the tables with their shorter-than-short skirts, re-applying lipstick and glowering at poor Miss Henry who has a heavy moustache and the shadow of a beard, They pose, sticking their flat tits out and riding their skirts as high as they can. they roll their eyes and perfect their practiced-bored look, blasé, permanently unimpressed.

p. 107

This is what we often call ‘well-observed’. We feel we know the scene laid out before us, and though we recognise the girls described have agency (they ‘arrange themselves’, they actively ‘pose’), it is agency in offering themselves to our eyes that merely co-operates with a superior narrative voice that judges them for their shallowness. This is so whether it is shallow dismissal of Miss Henry or the laugh we get from seeing how flat those over-exposed ‘flat tits’ are.

We laugh, perhaps warmly, but certainly with some superiority, at the short skirts and the over-obvious poseur quality that we are invited to find stereotypical, with yet the truths such stereotypes sometimes have, and ludicrous.

However later, the prose can lend its voice to Louise, who is aspiring to this detachment from the girls but we know that this is her because syntax and lexis contributes to a different register, one cruder than literary irony:

She pictures them walking in naked and licking each other out ‘cos they all think they’re so fucking amazing. Fucking cows.

p. 107

This is good not only because it’s style is nearer Kelman. It’s good because it shows that, although Louise’s evaluation of others is defensive and crude, it is barely different from the standard view of working-class characters in bourgeois fiction. Middle class literary traditions describe the working class and, in doing so, make them ‘other’ than the comfortable uninteresting world of the middle-class person sitting reading – with their unconsciousness of how funny they are to ‘our’ middle class acculturated eyes. Louise’s vision does that too more crudely but more honestly.

I would say, in the arrogance readers sometimes take on, that Fagan knows this. The author is beginning to show that this story is about the way Louise differentiates herself from her class, even before she knows it. That this is set in a school is important because Louise will differentiate herself in and through education.

If she grows, she grows because the child within her links her to a language not of her class but one that will enable her to talk about the features of the world with some distance from her absorption in her class. That is the language of biology and biological development.

Pluripotency, for instance – the story’s title, is the capacity of some stem cells in the foetus to differentiate according to ultimate function. They can become nerve cells (neurons) or skin cells or the cells of an internal organ. This gives Louise the metaphor that will change both how she sees herself, her emerging baby and the possibilities of the world, without the necessity, bound in the language of humanities of hierarchical judgements between persons and classes: worthy/unworthy, valuable/ unvaluable, high or low.

Thus, Fagan shows how her world will develop a potentially more productive self-consciousness through biological science and the insight will be fuelled by the innate democracy in women’s child-bearing powers. It will still feel at first like just getting OUT of the working-class and the values currently fed to them:

Somehow she feels cheated … Not good enough. … Louise cannot see that her own eyes are pretty. She may be somewhat plain compared to other people, bt she has an honest face and an an athlete’s figure. She does know though that she does not want to end up like her middle sister, full of plastic and silicone and cow’s arse fat; …

p. 108 my omissions

But that getting out of the working class is not seen as a self-exaltation. For Louise being better is the struggle of her class to see its own capacity for Pluripotency. She learns this, at 13 still shakily, by investing in the child of her class experience, regardless of the prick required to get it, that currently represented by the ‘cellular development of the foetus.’ (p. 108).

These kind of stem cells that have the potential to develop into any human type are called Pluripotent. She rolls the word around in a whisper and it disappears through the whistle of the trees. … She wills the cells to strive for perfection. She says in her mind over and over again, ‘you can do it! Don’t settle for less. I’ll settle for less if you promise never ver to do so, not even from day one’.

p. 109

There is a mother’s negation of herself for her child here like that in Lawrence’s Mrs Morel in Sons and Lovers but there is something else too – the sense that Louise herself has found that the world is not all just shit, although we have to acknowledge the shit. It is not only our children that can be perfect but the network of biological cells that work the same in all of us regardless of class and all have Pluripotency. I would say that Louise’s access to biological discourse is her access too to political discourse. When Louise gets hope it is hope for the redemption not of self but of a networked class.

It’s all shit.

Except the cells. The cells will not be shit. They will be perfect. Each and every atom. Each and every striving fibre. Complete perfection. It gives her hope, Her embryonic secret makes her smile.

END OF STORY p. 109

Is it just me, or has the hope spread now not just beyond Louise and her baby? Both of the former are kinds of self-centred hopes, if not less meaningful for that, but another hope is possible – that for a class that can only reach perfection in the networking of its parts?

Maybe here I write out of my own political expectations or from the accumulated effect of the Smashing It stories but for me the meaning of working-class art is that it is never the art of the individual but contains the content of a change so radical that it doesn’t break through the Class Ceiling without shattering the walls of the class system too, even if in our consciousness alone. To be working-class is to doubt the value of individual excellence on its own and to approach the communal ownership of the whole world. Salena Godden at the end of her piece ‘Broken Biscuits’ expresses it well in elaborating the making of art as an oyster generating a pearl:

You spend years gritting and spitting to make a pearl and so often it feels enough. If only we could see what pearls we are to each other. …

Now, let’s take over the whole biscuit factory.

p. 199

Steve

[1] In Chapter 13, in an attempt to convey the intimate tense presumed used in Spanish post-intercourse conversation, the hero asks: “But did thee feel the earth move?”

18 thoughts on “Reflecting on Jenni Fagan’s ‘Pluripotent’: A short Story in Sabrina Mahfouz’s (ed.) anthology (2019) ‘Smashing It: Working Class Artists on Life, Art & Making It Happen’”