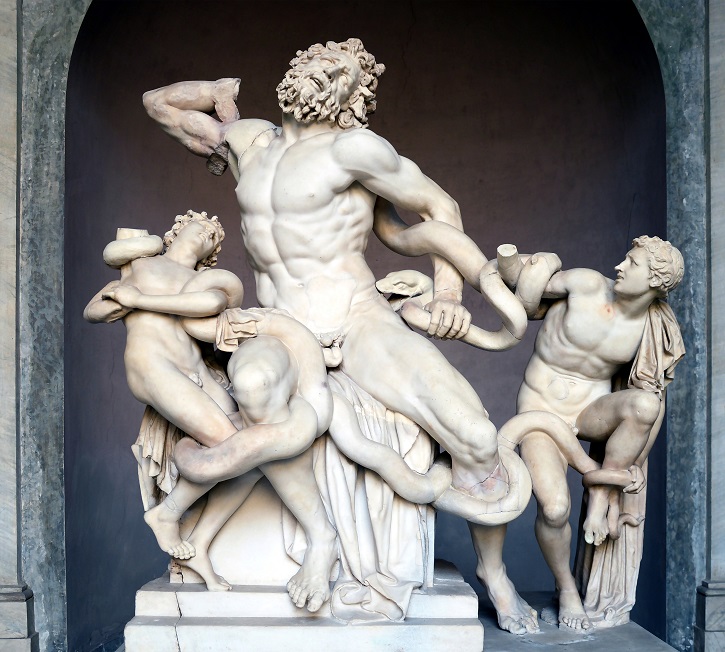

Laocöon: The struggle against constriction and limitation

As I read the essays in Curtis and Feeke’s 2007 catalogue of an exhibition called Towards a New Laocoon (sic.) in the Henry Moore Institute in Leeds, I find a central contradiction between:

- the reception of the work as full of uncontainable plenitude (of meaning, dynamic energy and the living body) on the one hand, and

- on the other as a disappointing work overly constricted in numerous physical and more abstract dimensions.

Unearthed in 1506, it has disappointed visitors to it and this effect is validated in Jens Daehner’s judgement that it is:

… not hugely rewarding visually. No perspective other than the regular frontal view has anything to offer the spectator. There seems little to be learned except how flat it is. … One single picture contains everything: from the front the figures are all lined up; they do not intersect, or even touch each other. How different the arrangements of figures are on the Pergamon frieze, which is often used for stylistic comparison! It is the purely visual readability of ‘Laocoon’ that has helped make it a universal image.

Daener, J. (2007:19) ‘Whose Laocoon (sic.)? The origins of a universal image’ in Curtis, P. & Feeke, S. Towards a New Laocoon (sic.) Leeds, The Henry Moore Institute.

This judgement further locates the work in a scale of excellence, based on a commentary by Pliny, that can be achieved in ‘lesser’ media. Achievable in more two-dimensional painting or unambitious bronze, it per se does not reach the potential excellence facilitated in sculpture considered as art at its most ’rounded’.

Yet when set against another medium, that of writing, which attempts to represent the reception of the work over and during time, Stephen Feeke says, that:

… the sculpture was so potent and full of possible meanings and readings that no one author could possibly grasp it.

… ‘it is impossible to contain in writing’

Feeke, S. (2007:9f.) ‘Legacies of the Laocoon’ (sic.) in Curtis & Feeke op. cit.

None of these arguments really compares like with like. In many ways the arguments are about the relative strength of different artistic media. However, I think they also capture an important effect of Laocöon. Is it, for instance, an artwork that has no essential meaning in itself but which leans out to varied audiences and suggests to each a different set of meanings and visual potentials? Or is it focused on a central meaning that binds audiences together in their response?

These alternative formulations are perhaps only available to us because of some of the ways Laocöon has been received in its history. In Renaissance Italy, for instance, it was possible for elements of the story of Laocöon to be emphasised that were not in more prosaic versions of the narrative in the eighteenth century. Virgil’s version of his story emphasised that the priest was attacked whilst in the middle of a priestly ritual, sacrificing a bull to Neptune. The snakes appear though from the sea precisely to turn the sacrificial object from the actual ‘huge bull’ chosen by Laocöon to Laocöon himself. Virgil seems to emphasise this by the simile he uses to describe the pain of the priest’s despatch.

All the time he (Laocöon) was trying to prise the knots apart with his hands, his priest’s headband soaked with slime and black venom; all the time his ghastly shrieks filled the air. It was like the bellowing when the wounded bull escaped from the altar and shrugged off the badly-aimed axe from its shoulder.

Virgil Aeneid 2. From http://www.users.globalnet.co.uk/~loxias/aeneidframes.htm

From bull-slayer to the gods, the priest becomes the object of the God’s divine hunger for ritual sacrifice.

Possibly fired by this, Renaissance iconography sometimes associates, as Madeline Viljoen asserts (Curtis & Feeke op. cit. p.23), the priest himself to an artist-magus connected to ‘the company of serpents’. If so, the figures represent a priest turned upon by the powers he has neglected in himself, receiving just punishment in the process.

This raises two possible interpretations of the snakes. First that they represent punishment by constriction of the power of the magus-artist, pulling the internal figures in to each other, constricting them too. Second, that they represent the way in which art makes wholes out of fragments, bounding the partial and discontinuous into a serpentine whole. Feeke (Curtis & Feeke op. cit. p.13) suggests that both Cragg and Paolozzi, as contemporary sculptors, utilise that idea in their re-inventions of Laocöon.

I’d like to think that these alternatives link to ways that Laocöon was received as either a contained and constricted narrative moment, in which all action is stilled, as Winckelmann seemed to see it in the eighteenth century, or as boundary-crossing aspect of art itself, spreading out through time in an unending set of versions of the problem of the artist’s endeavour – to struggle against that which constricts them personally or artistically.

With those ideas in mind the question raised in my mind was why, given the focus of the catalogue, the Henry Moore Institute, situated conterminously with the Leeds City Gallery did not use in its sparse exhibition (of 7 objects) a painting owned by Leeds from Keith Vaughan’s set of Studies for a Laocöon Group. These are described in he catalogue raisonné of Vaughan’s ‘Mature Oils’ on page 160. The Leeds one is Study for Laocöon Group II (1964) – see below.

This work needs to be seen in person to appreciate the use of paint so characteristic of Vaughan to suggest, quite unlike the original group, the interpenetration of bodies and skin, including those of the serpents, which fascinated Vaughan in the idea of the Laocöon. Indeed in Laocöon Figure (1964) the serpents were reduced to blue wavy lines and dabs representing the interpenetration of alien skins (here Laocöon and the serpents only, there being no other figures) into a whole.

The same blue thick brushstrokes are one manifestation of the serpents in the 1963 study, although they are even more fragmented in and across the whole. Moreover, here male figures proliferate and merge into each other.

A pair ochre-yellow and white buttocks turned to the viewer in the bottom left disappear into no recognisable body, although a frontal torso in streaked greys may either be obscuring it or it obscuring the other’s legs by taking a bent posture. A central pillar of streaked purple and blue may represent the column that the serpents form to hold their victims but otherwise, formed by multiple straight lateral strokes, is rather a pause in the act of more vertical brushstroke work that represents interpenetrating bodies to either side. A couple on the left appear to be linked by a kiss. A cruciform single figure to the left of them merges with them and a daub of lively paint suggests a drawn phallus.

Dynamism comes from sets of curved or arched arms forming a rhythmic pattern of curvaceous triangles along the top and the left of the picture. The overall effect is of links between figures that could either be the effect of an assembled social unit, of lovers perhaps, or party-goers, or of conflict – in which space shows aggression between the figures.

And maybe that is where art takes Vaughan from the idea of the Laocöon I have already tried to represent above. Oil paint and skin were cognate ideas in Vaughan and his art is at best where it seeks to show what an assembly of figures might look like, whether they assemble in love or antagonism.

In my view these assemblies are in Vaughan a representation of the social means by which queer love was constrained by law and sometimes turned into its opposite – hate, violence and betrayal. Hence his interest in St Sebastian and Crucifixions, replicated later in Derek Jarman.

Vaughan commandeered the myth we are dealing with and stated that it was about figures in conflict with each other, their surroundings and themselves as objects of equally strong desire and hate. He put it thus:

The idea behind the Laocöon myth, at any rate to me, is that it represents in supremely dramatic form man’s conflict with his environment and with himself, his own body.

cited Hepworth, A. & Massey, I. (Eds.) (2012:157) Keith Vaughan: The Mature Oils 1946-1977: a commentary and catalogue raisonné Bristol, Sansom & Company Ltd.

Steve