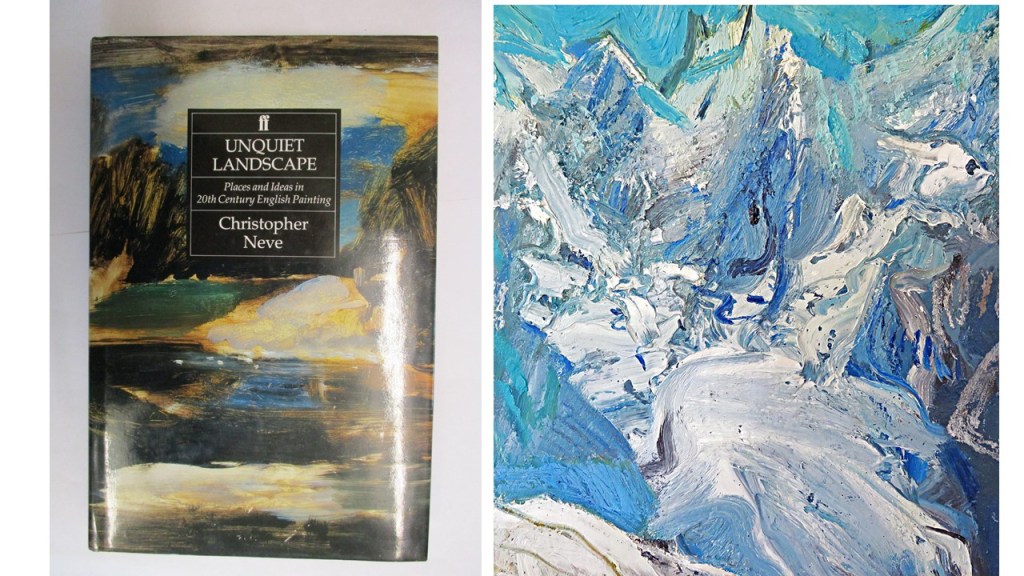

Christopher Neve’s Unquiet Landscape (2020 revision of 1990 work) London, Thames & Hudson and Doubles: a novel (2015) Kindle Ed.: Reading the unquiet but not silent self in novels and works on visual art

The cover of Doubles has a detail of Neve’s Glacier, an oil landscape, in which the strength and dynamism in the visible brushstrokes and resultant impasto effects convey something of what we mean by an ‘unquiet’ landscape – a pattern of discordant passages and pulsating but irregular rhythms. Full of shifts in space and time, the novel keeps reminding us that its probable temporal setting is May 1968 since the narrator’s ‘activist cousin’ is taking part in anti-De Gaulle events in Nanterre outside Paris (Neve 2015:L1280). In the next chapter he kills someone, a lax Orthodox priest, who turns out to be his father and marries (for a few days only) the person who turns out to be his mother – a kind of unearthed reinvention of the story of Oedipus and Freud’s version hereof.

The metaphors from music I use above are used to describe painting in both books. But ‘unquiet’ is a spooky word – it suggests the Gothic in the same way that the word ‘Undead’ does, in contrast with word ‘Live’. We do not have to look at Glacier long until we see the figure of a running man in it, animating the shadows of ice clefts and hills over the active flow of the static ice. There are noisy glaciers in the novel:

At nights the glacier was noisy. Its creaking and moaning were more noticeable than during the day, as if it was a restless sleeper, in a neighbouring bed.

(ibid:L642)

This restless neighbour is, though just a metaphor, one of the many doubles the narrator comes across temporarily or across large passages in the novel. Characters mirror each other in appearance and emotionally through projected or introjected identification. Suffering a black passage of grief (reproduced in the novel as a large black rectangle), the word ‘enantiomorph’ comes to the narrator’s mind as he examines the washroom mirror:

My left eye , I thought, is an exact enantiomorph of my right. In the mirror I am myself in reverse, unchanged but interchanged, myself but not myself.

(ibid:L1890)

The strange Mr Marakat sets the hero/narrator of Doubles the task of seeking out and killing his own doppelgänger (ibid: L2229) in Chapter 17, allows us to see that Neve did not choose the title of his work on the art of the early twentieth century without cause:

‘What interest me is disquiet,’ he said. ‘Chance controls more than half of all events. Our lives are filled with chance events which shape them, but fragments connect and relate, and I will tell you how.’

I have drifted into a medium in which I can never belong, I said to myself.

… ‘life is lived best when there is no story to tell.’

‘I know, but think of two, twin, twain, doubles, duplicity, mirrors.’

‘I think of little else,’ I said.

In this strange conversation the narrator is moved from a professed belief that his life is an uneventful one unworthy of record in any medium to the sense that he already contains the disquiet of ‘two’ or more other characters that he records profusely.

All records occur in a ‘medium’ – whether that be narrative, text, paint or patterned sounds in music. Once one is recorded, one is doubled – never now can one be only one but must be two or more appearances or metaphors of oneself. And we are never rid of ‘disquiet’.

After the most obvious candidate for a ‘double’ is killed by the narrator and the last morsels of that troublesome ‘other’ fed to the carnivorous plants at Kew, duplicitous selves still proliferate. Tried for another murder, one committed by his double, his painting process and medium is used as evidence of the real self that underlies the placid appearance of the man being tried:

…it has been implanted in the court’s mind that, because I paint with violent gestures, I am – like my mother – of an unstable and violent disposition.

ibid:L2692

Although there is much more to say about the theme of the double in this novel, that is not my purpose. Rather I wanted to show how that theme illuminated the creation of Unquiet Landscape, even though that work was first published some 23 years before the novel.

Neve’s method in this book is to suggest that the unquiet in a painted landscape is something put there by the artist quite unconsciously, and that this is somewhat similar (in some twentieth painters but not others – witnessing Ravilious in Chapter 2 for the latter) to what Freud and Groddeck called the role of the id (‘It’). In ‘Doubles’ he talks about his own fragmented prose as a medium too:

…dwindled, faded, slowly worn out by time, amounting to very little, but at least dug up, like Freud’s tomb figures in the end and exhibited to the daylight as traces of a human being, and of expired convictions.

ibid:L3573

Thus are the personalities of artists unearthed from the way the media used in painting are handled in Unquiet Landscape.

In my personal view the hero of this book is the painter whose influence shines out from Neve’s Glacier, David Bomberg, the main subject of Chapter 13 called ‘Appetite’. But note Bomberg was one of my heroes before I read Neve. The character unearthed is a Bomberg of immense appetitive desire, yearning to break through the crust of poor self-confidence and procrastination (p. 188). And Bomberg was, it is claimed, to express this ‘crucial truth of the human condition,’ in landscape. For the latter is:

not just the setting for man which provokes him to various reactions; in painting it is the man. David Bomberg did not only respond to landscape: there is a fervent sense in which he became it.

(Neve 2020:189f.)

This I guess is the way in which Neve in Glacier embedded in the landscape the running man that was himself, his recorded double, to which I have already alluded above.

Indeed his description of Bomberg’s working method is of a method motivated by need, desire and appetite, in landscapes illustrated in the book, such as Tendrine in the Sun (1947 – fig. xxxiii), could equally well describe Glacier:

Bomberg’s need in a picture in a picture was to find the ways in which shapes interlock in a deep space. It was what excited him. it means that there is often a rush of perspective from the foreground, articulated at each stage, calibrated towards a knot or some other complexity at the centre. And because he wanted to animate the whole surface of the canvas, he often used a high vantage point so that there was either no horizon or one that ran along the top edge. (my italics)

(ibid:190)

That ‘ran along the top edge’ describes the Bomberg but also the effects of Glacier, even the colour echo of the running man in the edges of the horizon. Likewise Bomberg’s method is of capturing his own double in a primitive act of murderous desire and that fills the description of the narrator as painter in Doubles (look out then for mirrors and second selves below):

…really he was looking for his own nature, his own individuality … mirrored in some way by the countryside. …

He recognized it as a part of himself and set about appropriating it and subsuming it with an appetite and passion that were almost violent . … You can see this when looking at a landscape painted by him. The view is pitched peremptorily into a tumult of the picture’s making.

(ibid:191f.)

The viewer remakes the appetite through the marks of the painting: strokes, rhythmic flows and shapings, dabs that are physical gestures of the body and feelings. Of the picture of Bomberg’s I show immediately above he says:

…he feels his way down an escarpment, twists through the gap towards the sea, stretches in ligaments of apricot and rose madder towards his tenuous hold on the horizon. (Neve’s italics)

(ibid:196)

This description will not appeal to art historians. It wears its subjectivity on its sleeve because that is all the painting contains: details of embodied action, thought and feeling. As he says it in his last sentence, subjectivity unites the ideal viewer with the artist as maker of his own subject (‘The unquiet country is you’ ibid:199).

It appeals very much to me. This isn’t how Neve proceeded through as a more sober art-historian, although certain ideas are common to that writing too, There is a dryness in his book on Leon Underwood, for instance, that you won’t find anywhere in Unquiet Landscape.[1]

But though Bomberg fits the over-excited noise of the unconscious in Doubles perfectly, Ravilious does not. Yet his descriptions of those paintings made me see them in my mind’s eye almost as perfectly as the example I saw in the Laing Gallery Newcastle last week. The subject here is ‘light-heartedness’.

Nor do his war landscapes, painted with cheerful absorption from what was in front of him day by day, carry portentous historical overtones.

(ibid:35)

The brush barely seems to touch the canvas here but Ravilious’ self is presumed to lie in that light-bodiedness as much as it does in Bomberg’s laboured frenetic overlapping impasto effects.

The sense of each artist being known in the medium of their work and in that work’s very process of making makes me, in this book, visualise paintings I have seen but infrequently and ones that I have seen many times in ways that make me want to see them again. Witness that, by now, least popular of English painters, Walter Sickert, in Chapter 6. Sickert’s subjectivity is to Neve a portal to memory: ‘the frame of mind of remembered places and remembered days.’ To look at this frames is to feel sensations:

…. what it is like to walk under a dark shop-awning or cross a road from shadow into light, where light and shade fall across everything with equanimity, … this colour on this particular afternoon.

(ibid:84)

Even the description of one of my great favourites, the queer artist, Edward Burra, described under the heading of ‘Hysteria’ still appeals. I recognise I am certain the feeling and the sense in the late Yorkshire landscapes:

…a fascinated disenchantment with the places themselves? He seemed to dread them. They swell, stretch. curve, crease. Bruised clouds stack over them and break open. Floods and fields make their puddles of watercolour. … Rock outcrops are swollen with disease. Chasms dwarf. Bile yellow and a punishing green can hardly contain themselves. …. But what gives the pictures their emotional potency is their raking depth to the horizon, their roller-coaster perspective.

(ibid:151)

It is my personal belief that this is the landscape of the homophobia that increasingly must have surrounded Burra and poisoned his earlier vivacious love of his painted sailors and drag queens in French navy towns or later in the Harlem of the 1920s, that mecca of artists, black and gay and more importantly black gay artists.

I resist seeing the constant evocation of disease as a reference to Burra’s bodily features, although I am certain his culture would have yoked this to his open articulation of a sexual self he felt unable to feed. But face it. It also describes fairly, if not in my own favoured way, even paintings not referred to by Neve, such as Near Whitby, Yorkshire (1972).

And there are so many painters who have justice done to them in this book who are forgotten more than they should be: or, in the case of Joan Eardley (chapter 8) forgotten in England if not Scotland. The material on the Nash brothers is superlative; distinguishing them as painter and persons as if both were the same thing. The new edition includes Sheila Fell (in Chapter 11) and that is a wondrous widening of the book’s scope.

It touches too on Neo-Romanticism without empathy or understanding (pp141-5). It hence diminishes serious queer artists who were in but all ‘came out’ of that group once it dissolved like John Minton, John Craxton and Keith Vaughan, the latter my favourite.

I recommend both books. Reading Neve enhances my capacity to enter into art in ways I prefer to the dry ‘objectivity’ that caused my recent tutors to say of my work as a learner recently something like: ‘Use established opinion in contemporary letter and more recent art historical criticism rather than your own unsupported opinion.’ I hope you can support the opinion or a ‘reading’ through evidence internal to the work. Neve frees you to do that. Just don’t do an Art History MA whilst in thrall to reading him.

Steve

[1] Neve, C. (1974) Leon Underwood London, Thames and Hudson

2 thoughts on “Reflecting on Christopher Neve’s ‘Unquiet Landscape’ (2020 revision of 1990 work) London, Thames & Hudson & ‘Doubles: a novel’ (2015) Kindle Ed.: Reading the unquiet but not silent self in novels and works on visual art”