Stigma is inevitable in Personality Disorder (PD) Diagnoses: A Very Personal View from a Non-Professional (retired mental health & learning disability social worker, former carer and long-term user of depression services).

The personality disorders are a collection of psychiatric categories each describing common clusters of ‘symptoms’. It is important to keep the term ‘symptoms in fright marks precisely because, although adopted by the medical model – in the form of the latest internal diagnostic manuals in psychiatry, those ‘symptoms’ are normally characterised by affects (emotions) and especially emotions that are considered not to be caused primarily by a present correlative event or object (such as being afraid of something you need not rationally be afraid of).

Indeed this is sometimes also true of ‘depression’ and ‘anxiety’ (the common mental health disorders). However, unlike PD, both depression and anxiety can be linked to similar embodied organic events, involving the nervous and other body systems. Those systems cover the whole body although this is often misunderstood by popular understanding that they concern ‘brain’ events. For instance the nervous system components attendant upon the stomach, though massively influential on certain functional systems of digestion and excretion, are rarely mentioned in the public record.

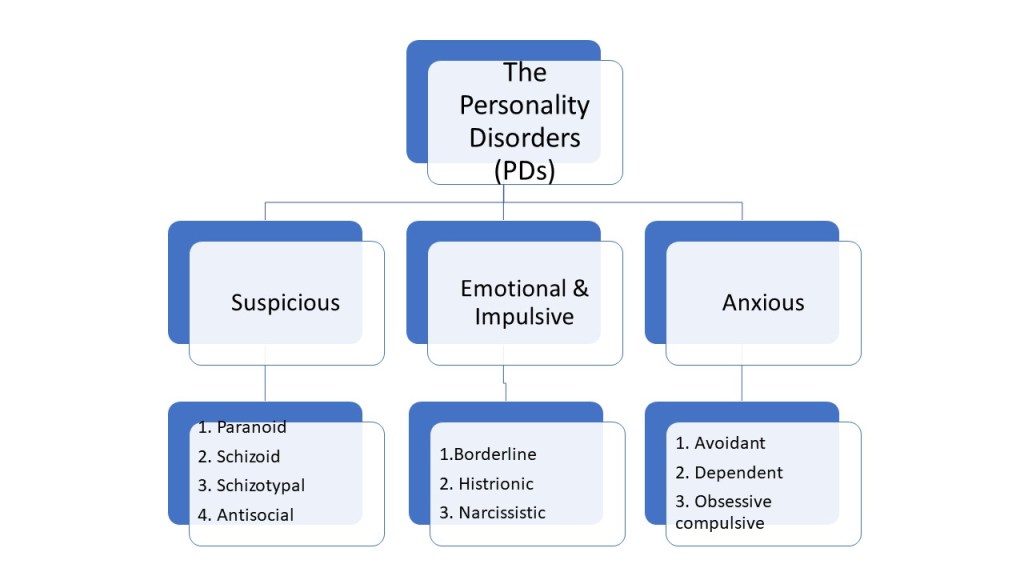

Mind’s introductory explanation shows the multitude of terms for the PDs under the usual mid-level categories and it is these we need to question, because the problems which attract stigma to the label start therein, I believe.

https://www.mind.org.uk/information-support/types-of-mental-health-problems/personality-disorders/types-of-personality-disorder/#.Xhs3dcj7Q2w

Each mid-level label describes personality traits but each trait is difficult to define without employing extremely fuzzy boundaries in those definitions. For instance, just consider how you might describe any of the theme without the term ‘fear’ or a synonym thereof.

Moreover, whilst ‘Suspicious’ types of PD are differentiated from both ‘Anxious’ and ‘Emotional and Impulsive’ types, this does not mean that all of these affective-cognitive states (which link emotion to ideation) won’t appear in all of the others and their sub-categories. It can be, and is, claimed that the type of feature characterising a certain sub-type is there because it is the dominant or hegemonic affect-cognition over a stated duration. But intensity and duration too might be affected by both psychological and social factors experienced concurrently over long duration. If they are psychological factors, they may be past memories of course but are concurrent in that these memories are salient in the period considered.

As already said, these fuzzily defined mental-emotive states are difficult to differentiate. Moreover, the balance of cognition and affect experienced or determined by an expert observer in each type can vary enormously by witness, time, space and culture. For instance, the presence of a cognitive representation of the object of fear can be more or less conscious. Note too that they can also be difficult to differentiate from the same label of experience, even by measures of intensity and duration, in non-diagnosed or differently diagnosed persons. Nevertheless intensity and duration matter and can be used to explain secondary behaviours, such as cutting or other form of self-hurting or damage including completed or uncompleted suicide, and cognitions, such as hopelessness, helplessness and ‘suicidal ideations’.

The problem with each of the mid-level category labels of PD is that they are, without exception I think, tied to developmental issues in the individual, particularly those experienced in childhood, and hence linked to failed development to some level of ‘maturity’ in which the emotions and cognitions are, if experienced, successfully regulated, controlled and/or managed. Each of these latter terms is used in the business to describe treatments for PD and their effect or as explanations of developmental skills that the person has failed to develop.

I nearly stopped myself in typing the word ‘failed’ but it is without doubt that the norm, being also considered a majority, does consistently define success in life or any aspect of it by such terms (perhaps more so in the twenty-first century than any other). Where and when people use the term ‘success’, a ‘failure’ in others showing no or less regulation, control and management is assumed or attributed.

The treatments are often appealingly described. Winnicott’s view that a child use ‘transitional objects’ (often in the form of toys or substitutes thereof) to successfully manage issues of suspicion, anxiety and emotional impulsiveness has returned, for instance as a popular description of some of the dynamics of developmental disorder attributed to PDs. And treatment tries to re-establish the trust necessary to control suspicion, anxiety or feeling of being overwhelmed.

What is wrong with all this?. In a sense the remediation of personality ‘deficits’ by using therapy as substitute for a phase of development that hasn’t been effectively experienced, or which has not succeeded in its goal (these stages are seen as teleological) seems a worthy role for a state conceived as ideal parent. But the developmental deficit idea is also used as the justification too for not helping people with PDs. For instance, people who need to learn ‘self-soothing’ or trust in traumatic crisis, it is argued must not be helped or supported lest they learn helplessness. They need, it is argued, to be ’empowered’ to act autonomously without help at all. To me this is arrant nonsense.

And I think it is so because the model of individual development that stages levels of success and failure for a child at different developmental phases cannot explain the fact that the distribution of PDs focuses on people socially disadvantaged in one way or another. Moreover, I suspect that reducing social disadvantage and creating more equal access to social goods that meet individual and social needs inevitably reduces PDs’ level of ‘presentation’.

PDs might be a way of representing the very real pain experienced by some people but it is not ever going to be a fair or accurate representation. It will always cause stigma because it labels the person with a strong presumption of immaturity or other inferiority to the norm.

Even when a person is pitied and treated nicely, which I’m told sometimes happens, it is because they are perceived as in deficit of what most of the rest of us have. And people, and let’s include mental health practitioners, seeing deficit in others project into them the most despised ways in which they themselves behave, think or feel and introject from another’s helplessness their own self-empowerment. Such dynamics, in relation to dementia, were described as the depth psychology of bad caring by Tom Kitwood.

So I don’t think the PDs can be restored. No doubt some ‘patients’ value the diagnosis and believe that they are treated appropriately under it. This might be so but that situation can continue without that label, just as we progress now without ‘dementia praecox’ as known to the young Freud or even without the widespread diagnosis of schizophrenia.

When people suffer emotionally, cognitively and as a result of behaviours they feel unable to control, or if they experience trauma in the past, present or both that isn’t resolved, they deserve the respect and assistance of the social commonwealth. Now, we only think we can do this by medical labels. When large numbers of people suffer but we can’t find a ‘diagnosis’ we fully believe in, a ‘sink’ diagnosis always emerges, such as ‘hysteria’ in the nineteenth century, and this is I think where we are with PDs at the moment. The label is used to help people attain support, appropriate or inappropriate, but it doesn’t describe bespoke treatments nor is it fully explanatory to the person or the supporting staff.