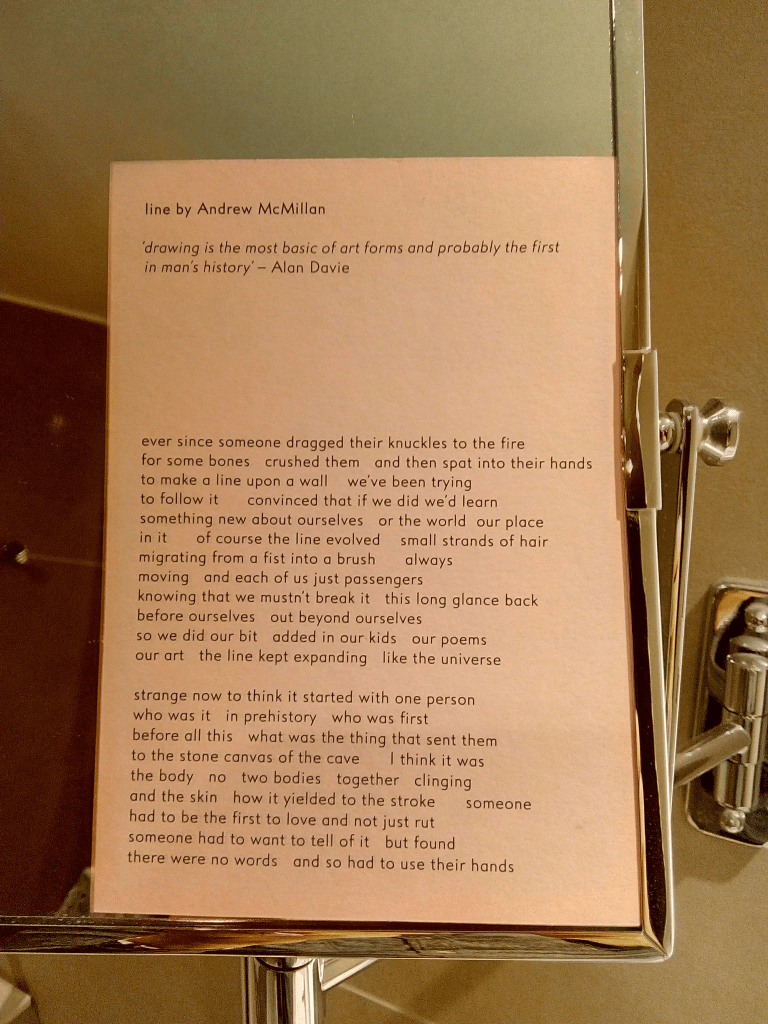

Andrew McMillan makes a poem about the origin of everything and a wonderful art exhibition: Alan Davie & David Hockney: Early Works at The Hepworth Wakefield to the 29th. Transferring to Towner Art Gallery. For the poet’s own take see: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T22jaegj8GQ

If you watch Andrew McMillan speaking about the genesis of his poem, line (at the link address above) you will pick up that he uses much of the terminology that is also prominent in the catalogue to the Hepworth’s wondrous Alan Davie and David Hockney exhibition.[1]

Clearly it’s an exhibition that plots a relationship between two artists, born at different times. It calls out for its significant ‘dates’ to be charted on some linear measure of duration, marking out the landmarks of innovation and influence on both sides. The great catalogue provides such a ‘timeline’ (pp.102-105).

Timelines embrace and plot possible flows of influence and counter-influence, but they inevitably fail to plot rich notions of origins and destinations. Of course, they are already good at thinner versions of such concepts such as births and deaths, those located in the biological career of individual organisms, but they are less adept at looking at the advent of concepts, such as ‘love’ or ‘desire’, or the long reach of influence in memory, even archival memory, and prospective anticipation.

Yet memorial influences matter in this timeline. For both artists these must include the poetry, but also the myths and extended significance, of Walt Whitman. Indeed for McMillan too the role of Whitman was to draw him into that same all-embracing relational timeline. And, as it does, it draws in other relationships important to all three – to words, forms, the visual and aural, textual and visual art. And it can’t stop there – the relational is networked.

All three of the artists articulate and imagine (in the sense of putting into the visual domain too – and words are visual artefacts too) concepts and affects that interact in interactive notions like ‘love’, ‘desire’, ‘sex’, ‘spirit’ and ‘the body’. Unsurprisingly body parts too express those interactions – ‘hand’ for instance can be name of written script, the laying down of other less readable marks, of different colours as well as a warm, living grasping and graspable body part that discharges embodied intentionality – in loving, communicating, and making iconic or textual art.

Then into this triad of artistic entanglement welcome Cavafy and his poetry of fulfilment and loss whether in individual lives across class divides or the history of his beloved Grecia Magna, Byzantium and Romano-Greek City of Constantine (Constantinople).

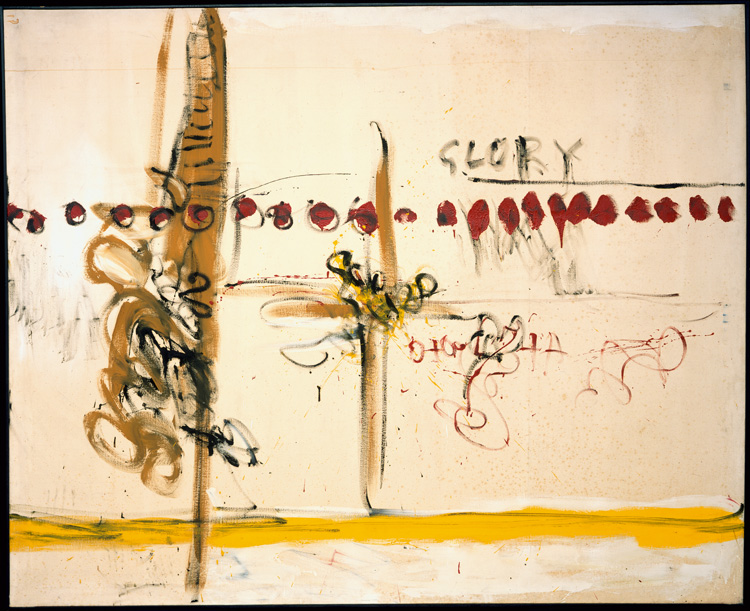

For a moment though leap back across our timeline to those pictures of Davie that captured so sensually his love of Byzantium, probably not through Cavafy, in his recreations within the idea of sainthood and divine glory of the human who both suffers and plays. Take, for instance, the wondrous artwork, Glory, (above) by Davie which combines text, icon, including the crucifix and blood-like marks or interrupted lines, smudged by bodies, anthropomorphic figures, text or cursives looking like an oriental calligraphy and lines.

If these interact, they do so because the physical mark leans through the cognitive and the affective in a viewer’s consciousness into meanings that are helped and hindered by reading words. We have to interact with this work and, in doing so, the whole-divided person, and perhaps even whole conflicting and harmonising, divergent and convergent communities tussle over achieving fulfilment and pleasure.

These are rich interactive contexts at play and we need to grasp at least some of them to enter into the poetic imagination of line, which evokes rich complicated timelines, lines as drawn or seen, mentally or physically – and even as rigidly hypostatised as a sense of cultural influence and/or biological heredity. Such ideas are better expressed in McMillan’s art:

… always

moving and each of us just passengers

knowing that we mustn’t break it this long glance back

before ourselves out beyond ourselves

so we did our bit added in our kids our poems

our art the line kept expanding like the universe

Well ‘expressed’ is a misleading term because so much depends on the sensitivity to form and this is a difficult concept, but it is what holds emotion and episteme together (since ‘moving’ and ‘knowing’ start contiguous ‘lines’) and yokes cultural and biological transmission together as a training of lineage. The quiet statement that our desire for significance is about putting ourselves in some ‘line’ or other speaks of the nature of perhaps some part of human desire, but it also makes the search for both origins and destinations subject to the doubts and fears that are equally human; of being ‘out of line’.

And that essential doubt is as much a part of the uneasy relationship with self and others that links the poets and artists we are considering here. Each seems to step out of line into origination, each longs for the re-linkage. It could be said to start with Whitman but maybe it starts much, much earlier. In the video McMillan cites Davies own myth of the origins of drawing, asserting a ‘first in man’s (sic.) history’.

McMillan pursues this line not only to the origin of art, as espoused by Davie, but the origin of the search for origins themselves. And too for destinations. To seek for the beginning is to seek for an end, a meaning or meaningful destination, most portentously stated in T.S. Eliot’s Little Gidding. [2] Less portentous and for me as beautiful:

to make a line upon a wall we’ve been trying

to follow it convinced that if we did we’d learn

something new about ourselves or the world or our place

in it ……

There is something beautiful about the contradiction of following a ‘line’ you yourself are making, as if inversions in time and space were as natural and more fun than continual games of ‘Follow my leader’! And go back to Davie’s Glory now and find a similar message about envisaged lines, some propel us forwards from left to right, especially if they are Western text, others in any linear direction. Some curvilinear shapes allow two dimensions and perhaps the illusion of three.

The need to move forward is so conditioned by the entanglement of our interest about the past that we may make ourselves passive – that is ‘passengers’ in McMillan’s trope in someone else’s drawing of our lives’ potential dynamics. We are happier, sometimes being a bit in the line, again as McMillan queries than its originator.

Hence when McMillan looks at an origin he looks for ‘one person’ initially but then finds that he probably prefers there to be two persons, who through exploration of each other find something in the body that is still not entirely contained by the body but seeks outward expression – through mouth but, probably at first through hands – the first example of ‘manufacture’ (making through hands – being of an object that represents the third term in a two-person relationship – what it means desire (or more basically ‘want’) made ‘to love and not just rut’.

someone had to want to tell of it but found

there were no words and so had to use their hands

What does it mean to have ‘no words’? Is it to imagine a time of concepts prior to words or of spaces where concepts, at that time, did not exist either for anyone or just for us? The making of words and making by hands come here together in a wondrous collaborative adventure to make an object of love, which is neither of the bodies of the two lovers (‘together clinging’) but this third term.

And if we turn to the catalogue of the exhibition, we see this very paradigm explored in a historical timeline, by Davie first and then Hockney; helped by memories of Whitman and the latter by Cavafy. Helen Little calls her beautiful chapter: Love Painting/Painting Love. Strangely, as Little shows, both artists tended to be represented in contemporary social records as extremely narcissistic. It is worth considering whether narcissistic body relations, somehow linked to something ‘other’, aren’t a necessary stage in the ‘creation’ of love objects. Both artists toyed with the idea of doll like creations – creations that feel like the transitional objects described by Winnicott. For Hockney this playfully morphed from a ‘Living Doll’ to the imago of Cliff Richard.[3] In paintings like Davies Dollygod No.3 (1960) and Hockney’s Study for Doll Boy No.2 (1960)

In Davie and Hockney, there is an initial interest in the image of body parts used to shock conventional viewers. Thus love becomes objectified in painting like Hockney’s Erection (c.1959), Love Painting (1960) and Davies Good Morning My Sweet No. 2 (1968). The boyish phallocentrism in both is the beginning of a symbolism that is still perhaps locked in what McMillan terms ‘rut’, but it aspires to create an image of wanting desire that aims to objectify love in paint, as well as painting using the bodies of love (one or two) to be made. Good Morning My Sweet combines part male and female sexual icons – the ‘morning glory remains a boyish joke but is only part of the creation.

There are many paintings in the exhibition that with different kinds of abstraction involved show exactly or in shadow what I feel in these two beautiful lines:

the body no two bodies together clinging

and the skin how it yielded to the stroke someone

Body parts but note that the skin yielded to stroke is the paint itself – becoming brushstroke – as well as love painted by those and other body parts.

A great poem for a great exhibition (and a great catalogue of essays).

Steve

[1] Clayton, E. & Little, H. (eds.) [2019] Alan Davie & David Hockney: Early Works London & Wakefield, Lund Humphries & The Hepworth Gallery.

[2] What we call the beginning is often the end

http://www.columbia.edu/itc/history/winter/w3206/edit/tseliotlittlegidding.html

And to make and end is to make a beginning.

The end is where we start from. (from Sec. V.)

[3] Clayton & Little (2019:101)

5 thoughts on “Andrew McMillan makes a poem about the origin of everything and a wonderful art exhibition: ‘Alan Davie & David Hockney: Early Works’ at The Hepworth Wakefield”