‘A scribbled form, drawn with a pen upon a parchment’: Reflecting on King John by William Shakespeare prior to seeing the current RSC production as screened to cinemas.

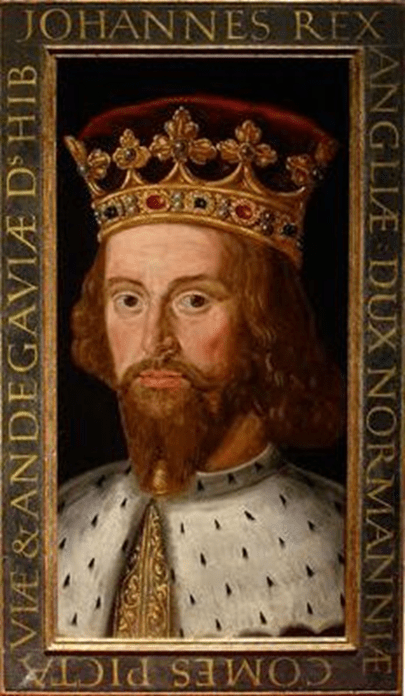

The historical King John ruled England from 1199 to the succession of his son, Henry III in 1216 after John’s death from, it is believed dysentery. The play toys with the idea John was poisoned by a monk, possibly part of its nationalistic anti-Catholicism as a play.

The death took place in skirmishes during a war of succession raised by Louis VIII of Francis (Lewis in our play), which was aided by a revolt of English nobles. Perhaps more important than say, the Magna Charta as an event in which John attempted to appease his nobles, omitted in the play, is another omission, the role of John through the reign of his older brother Richard I, the Lionheart in trying to usurp him, whilst the latter fought in the Crusades. His name runs through the play in the person of his illegitimate son, called Philip the Bastard in the script, who was the nominal son of Sir Robert Faulconbridge. His mother, Lady Faulconbridge admits to Philip:

King Richard Coeur-de-Lion was thy father

By long and vehement suit I was seduc’d

To make room for him in my husband’s bed.

(Act 1 Sc. 1 ll.253ff.)

This is a play full of strong mothers who stand behind the power of men, whose weakness of which men often shows. The roles of Queen Eleanor and Constance are almost starring roles – these women hold agency throughout the first half of the play, shaping the potential futures of their respective sons, John and Arthur.

More important I think is that it labours in its first half to focus the fact of legitimacy – the lawfulness of patrilineal descent as provable in a court of law – in relation to other issues of legitimacy. What, for instance, makes a man of note – a legitimate man, and what makes a King a true king? Both these issues predominate later in the play, in order to undermine John and restore legitimate succession through is son, Henry, and to test against John the greater quality of his brother Richard’s son, the Bastard. The latter will form himself a truer man than John but will bend the knee to Henry. Shakespeare intends us to see that lusty illegitimates, whoever their father, must subject themselves to the:

The lineal state and glory of the land!

To whom with all submission, on my knee

I do bequeath my faithful services

And true subjection everlastingly.

Act V, Sc.7, ll.102ff.

The language is precise. ‘The Bastard’ defines Henry III’s legitimacy as a ‘lineal’ matter but also as a matter of male faith in the contracts made by man. At the end, the two strong all the mothers are dead and men reconstitute bonds that remain patriarchal and found in the law that bounds and distinguishes true master and subject.

Early in the play we see why this position needed to be re-established. Whatever the faults found in him by the play, John stands for upholding patriarchal rules of legitimacy, those of marriage, against the inevitable potential falseness, as he sees it, of women:

KING JOHN to the legitimate son, Robert Faulconbridge.

Sirrah, your brother is legitimate;

Your father’s wife did after wedlock bear him,

And if she did play false, the fault was hers;

Which fault lies on the hazard of all husbands

That marry wives. …

Act 1, Sc.1, ll.116ff.

This is no mere joke between men. The inevitable truth that only a woman can truly assert the undoubted fact that a child is the child of their legal father, means that men should treat marriage as a risk but assert that it is the legal not biological relationship between father and son that determines patrilineality. This lesson will be underlined time and again in the play, even by the strong Queens who, in part dominate it. For instance, Constance, the mother of Arthur I of Brittany, whom Shakespeare represents as a child for reasons other than historical accuracy.

Constance’s role as a woman whose power depends on men and who yet is in the play a woman without any ‘men’ to justify her desire for power apart from having mothered a sickly unambitious boy, with legitimate lineal right to the throne. She is:

… sick and capable of fears,

Oppress’d with wrongs and therefore full of fears.

A widow, husbandless, subject to fears,

A woman, naturally born to fears;

Act 2, Sc. 2, ll.12ff.

Shakespeare’s powerless women are neurotically obsessed by powerlessness, for good reasons as the play will show. In the play as seen, they must be powerful attractive characters but essentially they are dependent on their men living up to their birth. She thus turns on her passive son, despite him being a child. She says to his plea that she be ‘content’ with political knockback :

If thou, that bid’st me be content, wert grim.

Ugly, and slanderous to thy mother’s womb,

Full of unpleasing blots and sightless stains,

Lame, foolish, crooked, swart, prodigious,

…

I would not care, I then should be content,

For then I should not love thee: no, nor thou

Become thy great birth, nor deserve a crown.

Act 2, Sc. 2, ll.42ff.

This onslaught of very conditional neurotic love equates a mother’s happiness with a son’s aspiration to fulfilling the birth she presents herself as having given him. It’s dark stuff socio-psychologically.

But it is also clear that some men do not ‘deserve a crown’, however proven their legitimacy. John is a case in point. A king whose legitimacy cannot be sustained by his action or ability to maintain his power when under duress. His legitimacy is of the law alone. He is a lesser man than his son and indeed than his brother’s bastard son, Philip. That his particular monarchy is an empty thing based only on written law is shown in one of the finest conceits in this play, and indeed many others. As his ‘bowels crumble up in dust’ at his death, he says:

I am a scribbled form, drawn with a pen

Upon a parchment, and against this fire

Do I shrink up.

Act 5, Sc. 7, ll. 30ff.

Does this mean that Shakespeare temporises upon the importance of the patriarchal law based on the written word, that he backs up to some extent the view that might is right and masculine physical power more than the mere word of the laws of succession and inheritance? I think it does to the extent that Shakespeare’s age could, and had to, bear this thought – especially during the troubled succession issues of the 1590s if this was indeed its date of writing – whilst closing the play on succession based on that law now hopefully represented by Prince Henry. Full of contradictions are the ways patriarchy sustains itself.

What is clear is that women in power are not to be trusted however majestic in appearance and dramatic effect, and Elizabeth I’s world was not afraid to show her that. Hence perhaps her insistence that in 1588 whilst at the height of power, “I know I have the body but of a weak and feeble woman; but I have the heart and stomach of a king, and of a king of England too”.

Arthur is probably a key element of this play and I wonder how you play this boy who swaps the most learned poetic conceits with his would-be torturer and murderer, Hubert, to avoid blinding by hot irons and death in the very strange Act 4, Scene 1.

This seems a good place to stop, since the purpose of this blog is to help me think out this play, which I had known so ill before, before seeing it played by RSC.

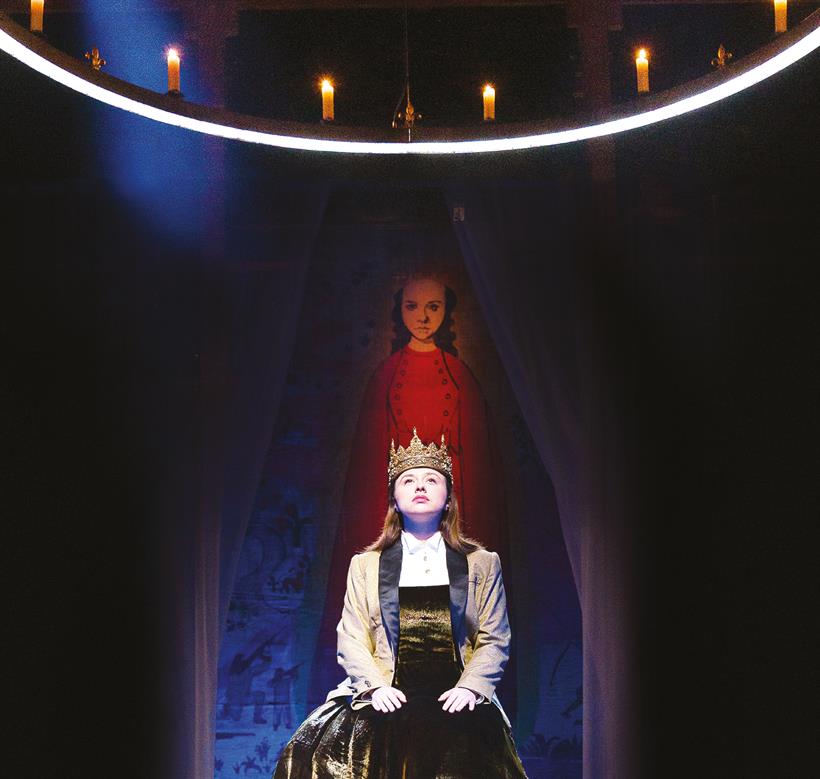

Their production may confront those issues or it may not. The joy of played drama is that it changes what we thought, if we know the play, what we were going to get and brings in something new. The decision to cast Rosie Sheehy as King John in a play so fraught with thoughts about gender and power will obviously have important consequences. Not least because in the website (but I may be not looking properly) I see no name for the casting of Arthur. The trailer shows a bias for the fun and the contemporary in the play of it all. Audience members speak of the ‘life’ put into a play that reads as ‘dead’. The text, BTW, isn’t ‘dead’ IMO but its take on power certainly needs renewal and a feminist direction is where it might find it. I can’t wait to see it.

Steve

So sorry I never got to see this play. A coronavirus debit!

LikeLike