Bhupen Khakhar: the intersectional queer body

My focus in this blog is the later large watercolour by Khakhar named Picture Taken on their 30th Wedding Anniversary 1998 (110×110 cm). It can be seen in the bottom right of the photograph below.[1] This shows the painting as it was displayed by the Tate at its 2016 retrospective. The theme I want to take is the challenges posed by taking on the representation of the gay male nude body. I will take it as read that male nudes have a long history in which the ideal of beauty is young, fit, conventionally and normatively bodily enabled in most contexts, and muscular (lacking fat or slackness of the skin).

But Khakhar’s nudes avoid these types entirely. Sometimes this is explained in terms of Khakhar’s own biography. His early lovers were often older men and as he himself aged he feared the loss of seminal potency following necessary surgery for prostrate cancer. His interest in the male body that has lost the signs that equate conventionally (both hetero- and homonormatively) with beauty was indeed life-long.

But in creating likenesses (and the possibility of liking) old male bodies were not the only boundaries crossed by Khakhar. The picture above the Wedding Anniversary represents the ‘deformed’ and ‘ill’ body: a man with five penises rather than one, with a ‘running nose’. Desire is made complex in the replacement of unity with multiplicity and desire compromised by disgust, perhaps not only in the ‘running nose’.

Khakhar’s sexuality was shaped by the severe laws of Raj India. His notion of the sexual body was scarred by the cultural ambivalences between a culture that celebrated multiplicity in polytheism and in male sexual careers, whilst containing sexuality by laws that remained ultra-Victorian. Thus while society in 1980s London, which he visited, was embracing diversity of sexual possibilities, gay India remain suppressed. In an interview, the gay male English painter Howard Hodgkin spoke of Khakhar’s:

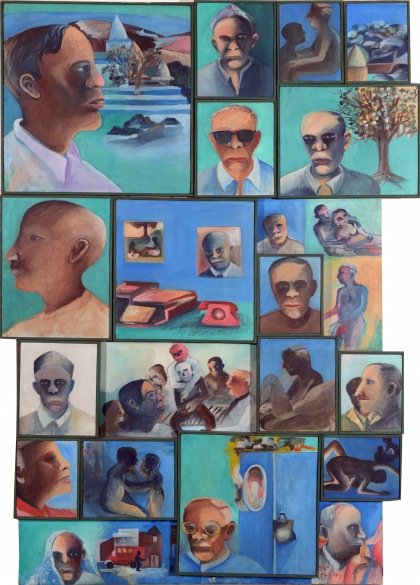

… complicated private life. He once painted a huge picture, I can’t remember now how many figures it contained, but they were all portraits of people he had slept with. He looked at me to see how I was taking it. All I could say was, ‘What an achievement!’.[2]

The painting is almost certainly Gallery of Rogues (1993) but these men were ‘rogues’ only in that Khakhar had slept with them. More importantly the huge assembly is also varied in age, gender (at least one appears as a woman), and number (one of the rogue single pictures is of a sexual group). This speaks relationally of a desire to contradict norms and to test them, to own one’s own promiscuity of desire and to enjoy the transgression it betokened. It is a picture that avoids easy framing because of the irregularity with its interior pictures fit together. Yet look too here at how bodies are varied in their apparent wellness of body and mind, often shown in deep eye-shading in some characters.

White-racist Imperial values had ‘soiled’ the very idea of Indian male bodies, and Khakhar prided himself in denying that his desire was boundaried by notions of beauty. Assumptions of ugliness itself was important. It seems part of the meaning of the figure Hathayogi painted in 1978, which sublimates the animal, pain and desire in sexuality into ritual images. He writes in a fictional diary of an illicit affair with a man marked by disease associated with poverty and class distinctions. He writes of one object of desire of his fictional lover whose face is caught in ‘tubelight’ whilst he undresses:

An illness years ago had scarred it. The shining head, the sweat drenched and pockmarked face looked ugly. Moreover the thin lips made it seem cruel too.

Sex may be imminent and must happen bit in his heart this lover is not seen in terms of ‘allurement, attraction had disappeared …’ but as an object of capture; an artist’s model:

A complete canvas full of the white vest, the white dhoti and the slight transparency that revealed the phallus. [3]

Here the very divergence of the figural type from notions of normative beauty become translated into the stuff of art. Khakhar’s art is seen as a container that can be full or empty of the stuff of desire and longing. That stuff consists of a multiplicity of diverse signs all caught up in the substitutive desire that art has become.

As a result, Khakhar’s art is often fractured. In it landscapes and urban communities are haunted by shadows that appear dark in their margins or joins only because they show what the overall landscape or townscape would deny as being there. Look for instance at the wonderful cityscape Pink City (1991) or landscape known as Green Landscape (1995).

But this is also the case in figural portraiture. Portraits are inevitably tied to rituals of human meaning. There is too much to say on this so I’ll rest with the idea of marriage because it is this which is explored in our great watercolour. Marriage between men had appeared I believe in disguised form in a painting of 1970 named (misleadingly on purpose I believe) Man Leaving (Going Abroad). This painting ritualises a relationship between men by formal garden imagery and an arch that might be serving as a mandap.

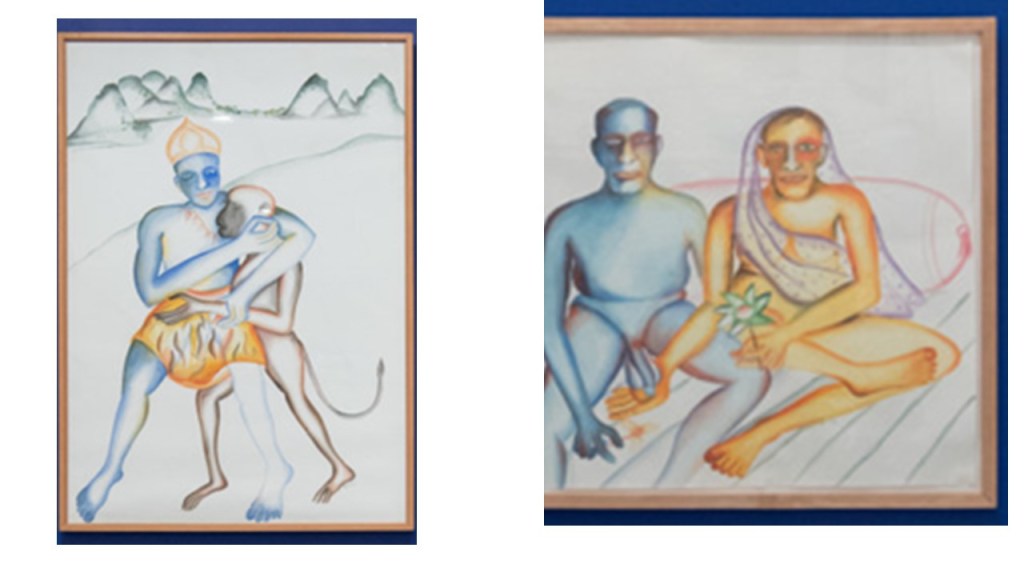

The two figures in the 30th Wedding Anniversary are clearly men. Both look similar in fact apart from nasal features and colour, which is entirely distorted.

A yellow male figure is clothed in feminine attire and holds a flower that is proudly erect, freshly alive, unlike the penis of his husband which is slack and limp, just as is the flower this blue figure holds in its other hand. Both figures are of older men with eyes portrayed as sunken and bodies well stacked with folds of fat and or slack flesh or skin. The contrast between phalli that are erect in young men and slackened in older men is also focal in the wonderful earlier Two Men in Banaras (1982).

The figures in the Anniversary gaze at us like the couple under a Hindu mandap. The gaze though is uncompromising. These men have become a portrait of life in diverse multiplicity – with variations in gender signed, not least by the incredibly phallic bolster behind them. The flaccid penis of the blue man that is fondled by the yellow man is an image of love as rich as any other. Its sexuality is queered because not normatively functional. And this is also figured in the fact that the yellow figure has transformed his phallic area into a lotus position and feminised himself in dress. These figures are not picturing what is being done in their relationship but symbols of bodies that adapt through age to the accidents of aging and life. They are an art that celebrates diversity without prettifying it or making it unreal. This may be done even more plainly in In the Coconut Groves (1993) where more casual male relationships are ritualised.

They are mythicised in the beautiful Yayati (1987) in which a younger green Khakhar is shown as an angel restoring the incomplete body of an older man (we don’t see his second leg) from waves of dust at the bottom of the picture-frame. The green angel cooperates in the older man’s act of masturbation, it appears, to strengthen it. More interesting still are the scenes of everyday life, in one of which two men kneel in front of a religious teacher at the top of the picture. The aim is to shoot diversity and multiplicity into the heart of conventional love tropes and to queer them to make them more really indicative of all life rather than rarefied lives once the sole staple of art.

Bhupen Khakhar is a wonder. There is more to be done too though on how Howard Hodgkin brought the very Indian art of Khakhar into modern queer art.

[1] Bhupen Khakhar, “You Can’t Please All”, Tate Modern, 2016, installation view. Clockwise from bottom left: ‘Sakhibhav’, 1995, watercolour on paper, 152 x 152 cm; ‘Ram Bhakt Hanuman’, 1998, watercolour son paper, 115 x 107.5 cm; ‘An Old Man From Vasad Who Had Five Penises Suffered From A Running Nose’, 1995, watercolour on paper, 102 x102 cm; ‘Picture taken on their 30th Wedding Anniversary’, 1998, watercolour on paper 110 x 110 cm. Image courtesy Tate Modern. From: https://artradarjournal.com/2016/07/09/truth-is-beauty-indian-modernist-bhupen-khakhar-at-tate-modern-london/

[2] Hodgkin (2016:80) in Bonacina, A. (2017) ‘An Interview with Howard Hodgkin in November 2016’ in Clayton, E. (ed.) Howard Hodgkin: Painting India London & Wakefield, Lund Humphries & The Hepworth Wakefield. 78-83.

[3] Cited Raza N. (2017:21f.) ‘A Man Labelled Bhupen Khakhar Branded as Painter’ in Dercon, C. & Raza, N. (Eds.) Bhupen Khakhar: You Can’t Please All London, Tate Publishing.