H817 TMA02

Steve Bamlett

Note: Open Up is a project of the fictional University of Coketown (imaginary)

| H817 TMA02 Contents | Page(s) |

| Contents & List of figures | 1 |

| Title page | 2 |

| Executive Summary (500 words: actual count) | 3 |

| Background | 4 – 7 |

| Policy | 8 – 15 |

| Benefits | 16 – 18 |

| Risks | 19 – 20 |

| Resources | 21 – 23 |

| TOTAL Words: 3182 words | |

| References | 24 – 26 |

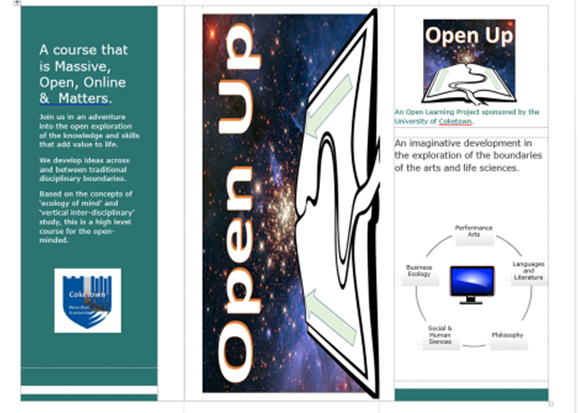

| Appendix 1: Mock-up of Open-Up Leaflet | 27 |

TMA01: List of figures

| Figure | Title | Page |

| A | An OPEN VIEW of Coketown Campus | 2 |

| B | The features of our Open Policy | 6 |

| C | Circle of Academic Practice-Sharing | 8 |

| D | Bar chart drawn from data in Comer et. al. (2014) | 10 |

| E | The CCPO Model | 14 |

Task:

Task: Our senior management group has heard a lot about open education, but they have little experience of it. You have been charged with writing a briefing document addressed to them about open education for their consideration.

This should conclude with a recommendation for them to consider, but it is not a fully costed business proposal. This recommendation can be in favour of open courses, suggest a strategy for the production of OER, suggest engagement with other initiatives, propose a cautious approach or be any mixture you deem appropriate.

(3000 words)

Imagined recipient: the Director of Open Innovations at the University of Coketown for submission to the Multidisciplinary Academic Board.

| Figure A: An OPEN VIEW of Coketown Campus omitted |

- Executive Summary

- This report recommends to Coketown University the trial of a MOOC in the Digital Humanities (DH) (Open Up – Appendix 1) as the first step to a more open education policy.

- It briefly details background issues including current socio-cultural changes in our contexts as a university, innovative technologies and new pedagogies, as a preface to a policy for an Open Educational Culture (OEC).

- That policy is described and rationalised in terms of changes to disciplinary configurations, pedagogies, role and relationships between teachers and learners, assessment, and ending on strong value-based recommendations. The aim in each case is to urge a move to a more ‘open’ form of operation, although initially these specific recommendations apply only to our proposed MOOC, Open-Up.

- The policy issues involve addressing our values and mission, change in the rationale of assessment and pedagogy as well as curriculum configuration towards an offering in DH less reliant on traditional boundaries in academia and its disciplines. A key theme is the utilisation of learners’ desire to be at the centre of educational change and process.

- Key benefits and risks of open approaches are critically described and weighed.

- It ends with some details of resources required to address some of those benefits and risks, especially those related to the changes occurring on the human-machine interface.

2. Background

2.1 Openness is an attitude to boundary-crossing, here explained as a response to:

- demographic, cultural and socio-economic contexts of the Humanities in higher education (HE) ;

- perceptions of the affordances of technology-enhanced learning (TEL);

- re-alignment of pedagogical and research practices in Digital Humanities (DH)

2.2 Socio-cultural context.

- ‘Liberal’ HE has experienced splits between ideologies of openness and closure in relation to its ‘external’ context since the philanthropically motivated distance learning of University College London in the nineteenth century (Thompson 1990:xff.).

- No university now relies on state funding nor offers a comprehensive higher education service, geared instead to uncertainties like competitive external funding (Leitner & Nones 2009) and learning choices made by discerning ‘customers’.

- We aim to provide services now relevant to new audiences, separated from us by distances of space or ‘culture’. Even ‘massive’ cohorts will buy only services targeted to specific needs in individuals.

- Humanities HE is no longer perceived as a set of unchanging traditional disciplines justifying practices and pedagogies from the past. Hence, the pedagogy of our pilot MOOC (Appendix 1) is designed to use e-resources that meet the challenges whilst being economically viable and sustainable.Ethical and other values of Humanities education are no longer assumed but require demonstration in response to cultural shifts in the nature of social authority and relationships.

- 2.3 Technologies

- Soft Springboards. Development of software resources that enable, and in some ways necessitate, open access (OA) to products of creative, intellectual and practical human knowledge and skills fast accrue. The current representations of this in DH are Open Educational Resources (OER). These phenomena increase connectivity between spaces, time, institutions, persons and groups as well as academic disciplines (Siemens 2015). Hard matter. Connectivity is impossible without devices that enable mobility across time, geographic and cultural space and experience.

2.4 Open Educational Practices (OEP).

- HE has a dual culture of research and pedagogy. However, openness aims for more integrated practices across both domains. Open integration is more than aggregation. Universities responding to pressures to separate research and pedagogy (Gibbons 2013), might instead open up barriers between them, such that neither is secondary to the other at whatever level of operation.

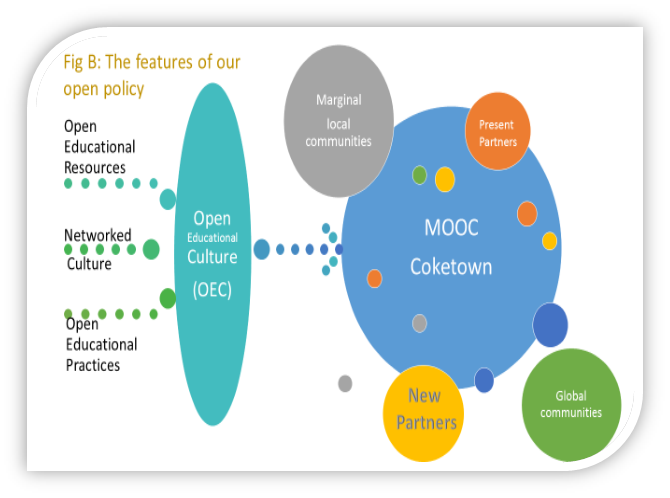

- Fig B above illustrates the blend of OEP, OER and an increasingly ‘networked culture’ of learners with Personal Learning Environments of their own that will scaffold our pilot MOOC. That scaffold we describe as Open Educational Culture (OEC).

3. Policy Describing OEC

- The policy areas covered elaborate the proposed rationale of ‘Open Up’, a pilot MOOC. They are:

- Open Disciplines (3.2);

- Open Pedagogy (3.3);

- Open Roles and Relationships (3.4), and;

- Open Values (3.5).

- Open-Integration interdisciplinary model

- Integrated curricular approaches of many HE academic domains are positively evaluated (such as medical studies in Brauer & Ferguson 2015) and in sister universities (Coventry in Blackmore 2009:5).

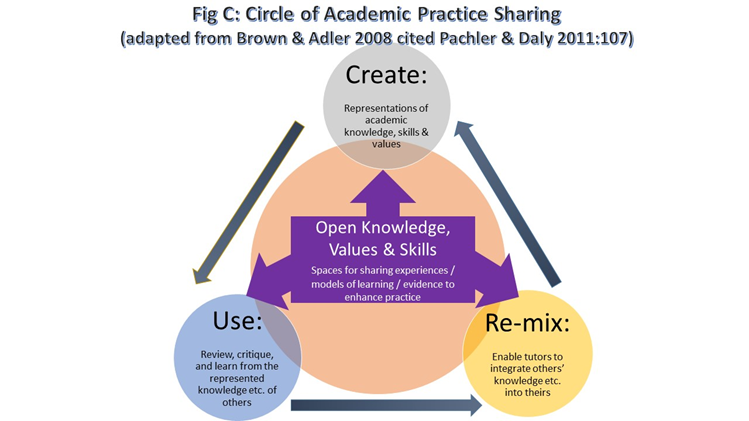

- Although integration within HE continues to be resisted as a threat rather than an opportunity (Bateson 2000a:viii, Evans 2002:18), Brown and Adler’s model (Fig C) of the affordances of e-learning stresses open exchange of data about knowledge, values and skills across multiple boundaries including academic disciplines.

- Integrated curricular approaches of many HE academic domains are positively evaluated (such as medical studies in Brauer & Ferguson 2015) and in sister universities (Coventry in Blackmore 2009:5).

- Open Teaching and Learning Practices.

- Developing ‘Writing’ Practices.

- Online Learning, more than any other pedagogic medium creates new spaces for ‘text’ as part of the learning process. Learners ‘explore the affordances of these writing spaces and literate forms are … renegotiated.’ (Barton & Lee 2013:16).

- ‘Written’ text remains a major expected outcome expected of HE. There is evidence to support the view that open exchange of writing between learner peers improves performance in this area.

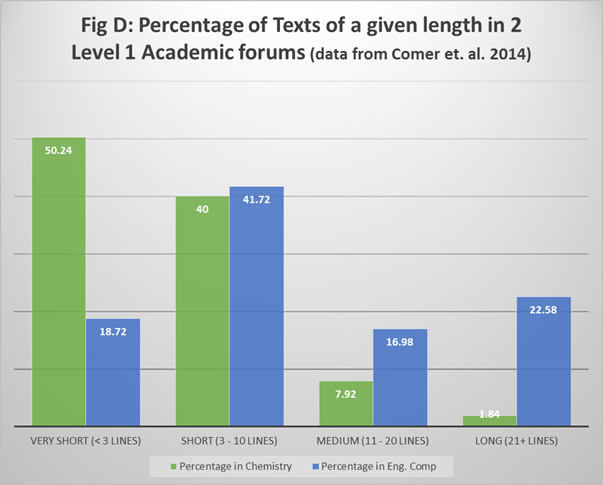

- Comer et. al. (2014) compare e-pedagogies utilising learners written interactions in forums to teach Year 1 Chemistry and English Composition. Although a very significantly larger proportion of English Composition learners reported learning gains comparative to Chemistry learners (62% compared to 38% respectively) this variation cannot be explained entirely by intuitive suspicions that this is because Humanities subjects are intrinsically attractive to those learners who prefer writing exercises. It is possible moreover that such suspicions are entirely based on stereotypes.

- A large part of this variance in aggregated report of learning gains was caused by the massive difference between the groups in the evaluation of peer review itself as a contributor to these gains. 97.45% English learners’ posts recorded learning gains specifically from peer review compared to 2.55% in Chemistry. The significant lever towards this difference appears to be that English learners were advised of the benefits to be gained from peer review, whilst Chemistry learners were not.

- Of course, examining the evidence, another explanation of the variance could be the disproportions in text size between the groups (fig D).

- Developing ‘Writing’ Practices.

- In Chemistry just over 50% of learners write ‘very short’ postings and, although both groups had similar proportions writing ‘short’ pieces, nearly 40% in English (compared to roughly 10% in Chemistry) wrote postings that were ‘medium’ or long’ in length. It is not implausible however to believe that the tendency to longer posts in English was also an effect of the stress in the learning process in that class on the value of peer review.

- Hence, Comer et. al (2014) not only yield evidence for the significant level of perceived learning gain in both groups, but also suggests that inculcating the culturally participative and openly shared aspects of writing pedagogy may influence the size of learner self-perceived gains.

- Developing co-productive making of multi-modal artefacts

- Online texts (some prefer the term ‘online artefacts’ because that term has lass traditional association with writing) employ multimodal media, whose boundaries are relatively more porous. Barton and Lee (2013:30) note that in Web 2.0 spaces, ’multimodal content can be co-created and constantly edited by multiple users.’ Hence, the multiple means by which co-produced artefacts in wikis can be edited. The icon of ‘acts of making’ multimodally is the object, concept and practice called ‘mashup’.

- Donaldson (2014) claims that ‘making’ across such boundaries demonstrates a reborn ‘constructivism’ which he names ‘authorship learning’. The very process of participatory co-production of artefacts fashioned from different materials (words, styles, genres, visuals, animation etc.) that is also aimed at real but ‘variegated’ audiences he describes as, ‘a process which involves systematic metacognition’. This is because working across the boundaries of many media enables (and perhaps forces) participants to articulate those boundaries to each other, demonstrating how they are thinking about their own and each other’s thought processes.

- Flexibility in roles and relationships.

- Metacognition, or learning about how one learns (especially in comparison with others), is also necessitated by openness. This is an open reconstruction of everyday roles and relationships within the learning process. Hence those roles and relationships may be thought of as disrupted, unstable and productive for that reason.

- Bayne (2004) found that OU learners, if not tutors, experienced identity displacements as part of the e-learning process. Using a Facebook group, Lee discovered learners, ‘often acted as teachers by initiating discussion while teachers would learn something new from these … posts’ (Barton & Lee 2013:159). These groups, which they name a ‘third space’ for teaching and learning, enable exchanges that ‘challenge, destabilize, and ultimately, expand the literacy practices that are typically valued.’

- Amongst those roles are research-based roles that universities have in practice separated from undergraduate pedagogic experience. Another is that of the ‘curator’: one who ‘looks after’ and preserves knowledge for later retrieval and re-use, including that garnered from original research at any level. Savage & McGowan (2015:77) conceptualise ‘curation’ as a principle of respect for the act of choice. E-curation is enabled by the agency of ‘mechanical’ algorithms, from a vast, perhaps otherwise overwhelming, repertoire of virtual repositories. It is a potential symbol of adaptive learning, and metacognitive in itself: ‘human, social ordering and making sense.’

- Open Assessment: The unfinished journey from Graded Closure to Open Judgement

- Marking ‘to a curve’ has always necessitated a kind of closure at the point at which learners are distributed, most necessarily in the realm of moderate achievement (the mean). Yet the assumptive, and perhaps ‘fictional’, world of normal distribution, the ‘bell curve’, has never had since Binet more than situated utility. Its function was marking out a small groups at the tails of the means for elite preparation or exclusion from HE respectively.

- In everyday settings, the value of acts of ‘certification’, a snapshot of achievement at one arbitrarily selected cut-off point is highly questionable. Feerick (2015:269) sees these acts as ‘barriers that held back the free sharing of knowledge and skills.’

- Lacking any developmental dynamism, they record that one once ‘knew something’ rather than preparing one for a world, and even the world of abstract thought is arguably like this, where change is the hegemonic reality. In the Humanities, just as in corporate settings, ‘where the form and substance of what you know’ is constantly changing continually updated certification could facilitate ‘what you declare you know’ to match and adapt to these changes. (adapted Freerick 2015:273)’

- Open Values

- The crisis in the ‘idea of the university’ is recorded by many witnesses (Evans 2002:106ff). Harper (2013:31) describes the ‘zombification’ of university culture, characterising the commercial culture of contemporary universities (to others known as ‘McDonaldization’) as the animation of a ‘dead’ liberal critical traditions that universities were once said to embody in vivo.

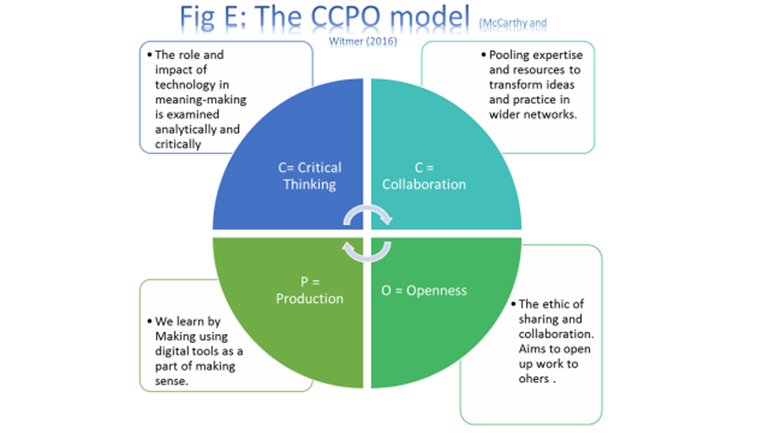

- McCarthy and Witmer (2016) review key research in ‘values-driven pedagogy’ focusing on digital HE in the Humanities (DH) and recommending a CCPO model (Fig E).

- This value base is recommended as policy because it assumes others such as open access, diversity, and a stable basis for the continual pursuit of change. That the last ‘value’ mentioned seems paradoxical may be explained by another claim for resting HD knowledge and skills on values.

- Hunt & Peach (2009:17) argue that the crisis in HE lies in its embrace of a value system of progressive quantitative but non-developmental growth, where innovation serves only that purpose. Citing National Wildlife Federation’s equation of current formulations of ‘growth’ with destruction rather than models of ‘sustainability’, these authors define the latter as production of ‘change-capable’ cultures. These cultures subsume the values described in CCPO.

- Benefits

- Raising

Tutor Expectations of Learners

- Pacansky-Brock (2011:2) argues that lowered teacher/assessor expectations of learner behaviour and potential achievement are merely reproduced in educational paradigms choosing to use ‘class time to deliver passive lecture content.’ In contrast, e-learning exploits ‘brain-friendly affordances’ (6ff.). Furthermore, she re-affirms, learners currently do concentrate on grade-related activity, but only ‘because we have created a system that allows them to do so’ (7).

- Ross (2016:14) equates the contradictions in the evidence for the efficacy of e-learning to the use of over-simple methodology and data to represent evidence for ‘what works’. Arguing for a methodology informed by speculative method, she says that it engages: ‘the world and its messiness more creatively, and critically, more imaginatively and inventively.’ Nussbaumer et. al. (2015) argue that modifying unitary authority models of teaching increases learners’ ownership of curricular content.

- Holmes (2016:25ff), in contrast, argues that this kind of characterisation of the efficacy of the lecture is not as yet supported by solid comparative evidence that favours constructivist or discovery methods. However, this evidence only compares face-to-face versions of both teaching styles and Pacansky-Brock (2009:6ff.) shows that this is not the issue for e-learning, which still utilises lecture type delivery but within the context of meaningful learner activity that can be presented as more engaging and, paradoxically involving greater pre-designed interaction and brain-friendly learning affordances.

- Daniel et. al. (2013:116) show that universities traditionally embraced exclusivity because restricted access was thought to guarantee high functioning learner entry. Such mind-sets are intrinsically unreceptive to openness.

- Research

- The culture of e-pedagogy is that of the ‘Maker’ (3.3.2). Whilst written linguistic products are an obvious outcome of internet practice, their use in re-envisioning the self, developing metalinguistic awareness and mediating hybrid experiences were unforeseen affordances of the medium (Barton & Lee 2013:66ff).

- However making on the internet affords grasp of the potentiality of multimodal forms and, according to Arola et. al. (2014), this contact with the variable affordances of multiple and hybrid communication practices supports learners’ ability to be communication producers.’

- Researchers too are not born but made. McCarthy and Witmer’s (2016) DH experience of the cross-fertilisation of teacher-learner roles at James Madison University was of, ‘ideas that reinvigorate or reconfigure curricular goals’ (generating) ‘research agendas that involve students and faculty across multiple years.’

- Considering

Cost

- Means et. al (2014:41) affirm HE has reached confidence in its technology infrastructures (both their own systems and those in the students’ ownership). Beginning to capitalise on the ability of e-learning to expand without submission to the ‘iron triangle’ that previously ensured that decreasing costs impacted on wider education access and quality (Daniel et.al. 2013:109f.), the time is ripe to join that process. Cost of education is increasingly shared between stakeholders in education and universities can concentrate on increasing access to, and quality of, their pedagogies (Daniel et.al. 2013:115f.).

- Raising

Tutor Expectations of Learners

- Risks

- Ethics.

- Forester

& Morrison (2001:10ff) show that openly networked societies confront

familiar ethical dilemmas in new forms of crime and intrusion. However, the

ethical interface of human-machine roles is still under-studied. They advise that

TEL-based curricula must themselves fill the ethical deficit. We build into

this programme:

- Critical awareness of the law and professional codes of conduct;

- Problem-based activities in ‘computer ethics’.

- Forester

& Morrison (2001:10ff) show that openly networked societies confront

familiar ethical dilemmas in new forms of crime and intrusion. However, the

ethical interface of human-machine roles is still under-studied. They advise that

TEL-based curricula must themselves fill the ethical deficit. We build into

this programme:

- Psychological

Threat

- Resistance to change in teachers is to be expected in relation to the perceived threats of role incursion by TEL. Although these threats have a basis, communities that face shared ethical dilemmas understand together the impact of varying distributions of costs and benefits between stakeholders.

- Turkle (2015:305f.) insists that because ‘self’ is surrendered to the generalised ‘self-surveillance’ of the web, this is a source of contemporary anxities. Terms for new ‘anxiety’ conditions like FOMO (an acronym of ‘fear of missing out’) are now added to dictionaries (Crook 2016). In the light of the capacity of social anxiety for co-morbidity with depression (APA 2013:208) threats to mental health should not be dismissed. Preliminary guidance should be offered to applicants.

- Open

assessment may be misunderstood and misrepresented by central stakeholders such

as funders, employers.

- Wiley (2015:9) has argued that a fully developed infrastructure, including ‘open assessments’ for open education has yet to be achieved. Noting that guarded and closed assessments ‘claim to be the only ‘secure’ form of assessment, Wiley poses solutions. However, these are as yet in their infancy. This issue therefore needs further examination.

- Ethics.

- Resources

- Tooling

Up

- McCarthy

& Witmer (2016) resisted building ‘large in-house tools’ to accomplish TEL

goals: employing tools that for many learners were:

- independently accessible;

- inexpensive or free, and;

- easily learnable with minimal or peer consultation.

- These tools include names like Ngram Viewer, Storify, and Thinglink.

- McCarthy

& Witmer (2016) resisted building ‘large in-house tools’ to accomplish TEL

goals: employing tools that for many learners were:

- Resourcing

Quality

- One persistent myth that the eMOOC tradition aimed to correct (Siemens 2005) is the total reliance of pedagogy on ‘human presence’ to mediate the world of OER to learners. Some MOOCs utilise mythologies about the passive character of ‘active’ student-hood (Knox 2016). xMOOCs insist that OER are mediated by tenured staff, rather than being available to learner peer-group discovery, thus reinforcing belief in the necessity of a ‘human touch’ in teaching represented by, at least ‘virtual’ human presence..

- However, Balula & Moreira (2014:19ff.) developed a model for evaluating e-pedagogy not based on quality of teacher-learner contact alone. The model enables rich ‘3-dimensional’ representations of the four varieties of interactions learners should expect from online education. Hence, this model does not demand sine qua non costly embodied ‘teacher presence’ but sees ‘human touch’ in other sources too.

- Tooling

Research

- Some

research-academics articulate views that open access (OA) licences threaten

their rights as potential producers, not least when barriers to journal

publication or article access are relaxed:

- First by admitting competition from outside faculty peer groups;

- Second, by providing low or no cost access to journal articles thus reducing potential income.

- To Suber (2012:47f.) both issues are caused by the construction of writing as a ‘rivalrous object’: charging for access, enforcing both exclusion and scarcity. Although free access journals preserve quality, to some extent by lesser forms of exclusion, such as that implied in distinctions between green and gold standard e-publications (Suber 2012:52ff.), he endorses university consensus favouring ‘green’ policies, where articles are found and stored in open repositories rather than in e-journals (Suber 2012:150ff). A key resource then are OA journal repositories. ‘Open Up’ is thus enabled to take from and submit to useful research-based projects.

- Some

research-academics articulate views that open access (OA) licences threaten

their rights as potential producers, not least when barriers to journal

publication or article access are relaxed:

- Machine

/ Human Interface

- Suber (2012:120ff.) also considers machines to have a right of OA. Although this argument feels counter-intuitive, bots will increasingly mediate academic research even in traditional settings. Algorithms reduce tasks that were once the basis of the stereotype of the ‘academic drudge’. Machines perform literature searches, quantitative and qualitative data analysis, including systematic analyses between studies.

- OA for machines facilitates data-processing skills that de-mystify research. Uncreative and ‘mechanical’ labour, as represented by Eliot’s Casaubon in Middlemarch with his manual coding systems, is not worth preserving merely because it is ‘real work’.

- Similarly even less ‘mechanical processes’ could be open to machines, as Ross (2016:9ff) shows in her three case studies of technological applications in the teaching and learning process. Here agency in tasks once thought exclusively the realm of human teachers is distributed instead across human-machine interfaces: assessment, recording, evaluating, realising, and even teaching and that quite openly, unlike the counter tendency in ‘stealth assessments’.

- Tooling

Up

- References

APA 5th ed. (2013) DSM-5: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition Arlington, American Psychiatric Association.

Arola, K.L., Ball, C.E. & Sheppard, J. (2014) ‘Multimodality as a Frame for Individual and Institutional Change – Hybrid Pedagogy’. Available from: http://www.digitalpedagogylab.com/hybridped/multimodality-frame-individual-institutional-change/ (Accessed 07/02/2016).

Balula, A. and Moreira, A. (2014) Evaluation of Online Higher Education: Learning, Interaction and Technology Heidlberg, Springer Education.

Bamlett, S. (2016). ‘Fictional Project Leaflet for Fictional Director of Open Innovation’ BLOG. Friday, 15 Apr 2016, 13:53. Available from: http://learn1.open.ac.uk/mod/oublog/viewpost.php?post=175927 (Accessed 22/04/16)

Barton, D. & Lee, C. (2013) Language Online: Investigating Digital Texts and Practices Abingdon, Routledge.

Bateson, M.C. (2000a) ‘Foreword’ in Bateson, G. Steps To An Ecology of Mind Chicago, University of Chicago Press, vii-xviii.

Bateson, G. (2000b) Steps To An Ecology of Mind Chicago, University of Chicago Press.

Bayne, S. (2004) ‘Deceit, desire and control: The identities of learners and teachers in cyberspace’ in Land, R. & Bayne, S. (Eds.) Education in Cyberspace London, Routledge, 26 – 41.

Blackmore, P. (2009) ‘Framing a Research Community for academic futures’ in iPED Research Network (Ed.) Academic Futures: Inquiries into Higher Education and Pedagogy Newcastle upon Tyne, Cambridge Scholars Publishing. 1 – 12.

Bonk, C.J., Lee, M.M., Reeves, T.C., & Reynolds, T.H. (Eds.) (2015) MOOCs and Open Education Around the World New York, Routledge.

Brauer, D.G. & Ferguson, K.J. (2015) ‘The integrated curriculum in medical education: AMEE Guide No. 96’ in Medical Teacher 37, 312-337.

Comer, D.K., Clark, C.R. & Canelas, D.A. (2014) ‘Writing to Learn and Learning to Write across the Disciplines: Peer-to-Peer Writing in Introductory-Level MOOCs’ in The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning 15 (5) Available from: http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/rt/printerFriendly.1850/3066 (Accessed 30/03/16).

Crook, J. (2016) ‘FOMO, TMI and ICYMI added to Merriam-Webster dictionary’ in TechCrunch Available from:http://techcrunch.com/2016/04/21/fomo-tmi-and-icymi-added-to-merriam-webster-dictionary/ (Accessed 21/04/16)

Daniel, J., Kanwar, A., Uvalić-Trumbić, S. (2013) ‘Q: Will E-Learning Disrupt Higher Education? A: Massively!’ in Schreuder D.M. (Ed.) Universities for a New World: Making a Global Network in International Higher Education, 1913 – 2013. New Delhi, SAGE Publication, 99 – 120.

Donaldson, J. (2014) ‘The Maker Movement and the Rebirth of Constructionism – Hybrid Pedagogy’. Available from: http://www.digitalpedagogylab.com/hybridped/constructionism-reborn/ (Accessed 07/04/2016).

Evans, G.R. (2002) Academics and the Real World Buckingham, The Society for Research into Higher Education & Open University Press.

Feerick, M. (2015) ‘ALISON: A New World of Free Certified Learning’ in Bonk, C.J., Lee, M.M., Reeves, T.C., & Reynolds, T.H. (Eds.) MOOCs and Open Education Around the World New York, Routledge, 269 – 274.

Forester, T. & Morrison, P. 2nd Ed. (2001) Computer Ethics: Cautionary Tales and Ethical Dilemmas in Computing Cambs, Mass, MIT Press.

Gibbons, M. (2013) ‘The Rise of Postmodern Universities: The Power of Innovation’ in Schreuder D.M. (Ed.) Universities for a New World: Making a Global Network in International Higher Education, 1913 – 2013. New Delhi, SAGE Publications, 331 – 351.

Harper, R. (2013) ‘’Being’ post-death at Zombie University’ in Whelan,A., Walker, R. & Moore, C. (Eds.) Zombies in the Academy: Living Death in Higher Education Bristol, Intellect, 27 – 38.

Holmes, J.D. (2016) Great Myths of Education and Learning Chichester, Wiley Blackwell.

Hunt, L. & Peach, N. (2009) ‘Planning for a Sustainable Academic Future’ in iPED Research Network (Ed.) Academic Futures: Inquiries into Higher Education and Pedagogy Newcastle upon Tyne, Cambridge Scholars Publishing. 14 – 27.

Knox, J. (2016) Posthumanism and the Massive Open Online Course New York, Routledge.

Leitner, K-H. & Nones, B. (2009) ‘The Challenges of Competitive Funding at Universities: A Study of the Ratio between Core Budget and External Funding’ in in iPED Research Network (Ed.) Academic Futures: Inquiries into Higher Education and Pedagogy Newcastle upon Tyne, Cambridge Scholars Publishing. 42 – 60.

McCarthy, S. & Witmer, A. (2016) ‘Notes Toward A Values-Driven Framework for Digital Humanities Pedagogy – Hybrid Pedagogy’. Available from: http://www.digitalpedagogylab.com/hybridped/values-driven-framework-digital-humanities-pedagogy/ (Accessed 07/04/2016).

Means, B., Bakia, M. & Murphy, R. (2014) Learning Online: What Research Tells Us About Whether, When and How New York, Routledge.

Nussbaumer, A., Dahn, I., Kroop, S.,Mikroyannidis, A & Albert, D. (2015) ‘Supporting Self-Regulating learning’ in Kroop, S., Mikroyannidis, A & Wolpers, A. (eds.) Responsive Open Learning Environments: Outcomes of Research from the ROLE Project Cham., Switzerland, Springer International Publishing, 17 – 48.

Pacansky-Brock, M. (2013) Best Practices for Teaching with Emerging Technologies New York, Routledge.

Pachler, N. & Daly, C. (2011) Key Issues in e-Learning: Research and PracticeLondom, Continuum.

Ross, J. (2016) ‘Speculative method in digital education research’ in Learning,

Media and Technology, DOI: 10.1080/17439884.2016.1160927. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2016.1160927 (Accessed07/04/16).

Savage, J. & McGown, C. (2015) Teaching in a Networked Classroom Abingdon, Routledge

Siemens, G. (2015) ‘Foreword 1: The Role of MOOCs in the Future of Education’ in Bonk, C.J., Lee, M.M., Reeves, T.C., & Reynolds, T.H. (Eds.) MOOCs and Open Education Around the World New York, Routledge, xiii – xvii.

Suber, P. (2012) Open Access Camb., Mass., MIT Press. Also available for free download: https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/open-access (Accessed 22/04/16).

Taylor, A. (2014) The People’s Platform: Taking Back Power and Culture in the Digital Age London, Fourth Estate.

Thompson, F.M.L. (1990) ‘Introduction’ in Thompson, F.M.L. (Ed.) The University of London and the World of Learning 1836 – 1986 London, The Hambledon Press, ix – xxviii.

Turkle, S. (2015) Reclaiming Conversation: The power of Talk in a Digital Age New York, The Penguin Press.

Wiley, D.

(2015) ‘The MOOC Misstep and the Open Education Infrastructure’ in Bonk, C.J.,

Lee, M.M., Reeves, T.C., & Reynolds, T.H. (Eds.) MOOCs and Open Education Around the World New York, Routledge, 3 –

11.

Appendix 1:

Mock-up Leaflet for the Proposed Pilot MOOC in the Humanities and Social Science at Coketown, ‘Open Up’ (a foldable 2-sided leaflet).

One thought on “The ‘Open’ Up Teaching & Learning Project”